This Day in Labor History: December 30, 1900. Advisors from Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the college run by Booker T. Washington, arrived in Togo to help German colonialists institute a southern-style cotton regime in their African colony. Let's talk about this shameful event!

This moment demonstrates the globalized nature of the American cotton production economy as it developed after the Civil War, as well as the active assistance of the nation’s leading black institution of higher education in propagating it.

In 1895, Booker T. Washington gave his famous Atlanta Compromise speech, when he told a white audience that African-Americans should give up on fighting for political rights and instead just work hard, while whites support that work, especially his own Tuskegee Institute.

The setting for that speech was the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition. In the audience for that gathering of cotton capitalists was Baron Beno von Herman auf Wein, the agricultural attaché to the German embassy in Washington.

The Baron was very interested in learning from American agricultural techniques. He, like many white elites on both sides of the Atlantic, believed that cotton growing was best done by black labor in some sort of forced or semi-coerced manner.

The end of slavery in the United States had popped the myth that slavery was required for cotton; as the colonial powers quickly found out, there were other ways to force people into the fields.

Meanwhile, Washington himself began to see the Jim Crow South as a model for international colonialism.

He stated, “Everywhere, especially in Europe, people are looking to us here in the South, Black and White, to show to the world how it is possible for two races, different in color, to live together on the same soil, under the same laws,...

... and each race work out its salvation in justice to each other.”

That Washington actually believed this stuff is a bit hard to believe, but the evidence largely points to his sincerity here being true.

That Washington actually believed this stuff is a bit hard to believe, but the evidence largely points to his sincerity here being true.

Europeans had sought to grow cotton in their colonies back into the early 19th century. They did not want to be reliant on American cotton.

It happened with varying degrees of success, but given the superior fiber of American cotton, it was still the preferred source to the end of the 19th century.

The Germans wanted to break their dependence on American cotton and thought the Tuskegee model might be the path to do so.

Like Washington, they saw the Jim Crow South as the model, but figured with German efficiency, they could perfect the system and make the people of Togo more docile and produce more cotton than in Alabama.

It was in 1889 that the Germans discovered that people in the interior of Togo grew cotton. These were the Ewe people. They believed that they could convince the people to take all the German ways of doing things and apply it to their own lives.

And if they wouldn’t do that themselves, well, they could be forced to do so. But of course Ewe had their own economic traditions. There was a lot of economic independence in households. Women controlled much of the trade.

Women shared a husband, who lived with none of them, and they did the farming with their children. Husbands had to provide serious gifts in exchange for companionship, but still had ultimate authority over much of society. Women grew cotton and spun it.

Men might help with some of the farming, but that was it. The Germans found this all backward and wanted to transform Ewe culture into a modern globally-facing export-based cotton plantation economy.

In 1900, Baron von Herman contacted Washington about lending a hand. Washington agreed and sent three leading recent graduates in agriculture and from Tuskegee, as well as one professor, to Togo and they arrived at the end of that year.

John Robinson, one of the Tuskegee graduates, started a school in that land in 1904 specifically to teach people how to grow cotton in plantation-style agriculture.

The Germans, engaging in a violent colonialism, required graduates to return to their home regions and produce cotton for the European market.

Between 1904 and 1909, the amount of cotton leaving Togo for Europe grew sixty-fold and also improved in quality, with observers in both the United States and Europe commenting approvingly on Black people from the U.S. teaching Africans the proper methods.

The position of the Tuskegee men who assisted in this was complicated.

Robinson was not supportive of the German idea of using cotton production to control Africans, writing, “I stand for more than cotton” and that “we wish to make them better traders,” training people in agriculture generally.

But regardless, the impact he made was to place the people of Togo under the yoke of German masters.

Through the help of the Tuskgee advisers, the Germans replaced the extended Ewe household economies that ensured self-sufficiency with small tenant farmers like in Alabama, effectively tying workers to the land and keeping them in debt and poverty.

Both the Germans and the Tuskegee advisers believed that Black people imitated others better than whites and used this racist idea to shape their actions. Washington himself the best thing about Black people was their ability to imitate the best in whites.

Said James Calloway, one of the Tuskegee men, when they stopped in Liberia on the way to Togo, “The Negro who comes here from America must work and thus he teaches the native to work.”

All of this would be disastrous for the Ewe. The long-held autonomy of women both in the economy and at home was already fading under the influence of the European-driven market economy. The yarn spun by the women of Togo was undermined by cheap cotton imports.

The German military forcefully destroyed the pottery industry that gave women autonomy. Western ideas of domesticity began to infiltrate homes and oppress women in new ways.

Both the Germans and Tuskegee wanted to undermine the polygamy of these people through ending the economic relationships that made this possible. New work regimes also meant new social regimes and gender norms.

The experiment also didn’t work well. Lots of people were fleeing the German occupation and the death that came with it. The Tuskegee cotton farms only exacerbated this migration, as did a drought.

For those who remained, subjection to German authority was required, as was specific work requirements that transformed societies. The people of Togo had to sell their cotton to the Germans or face physical punishments that included flogging and forced labor.

This was to ensure that Togo became reliant on the German colonizers and not maintain economic independence by weaving their own cloth as they had done for centuries. Young men were forced to leave home to attend German schools run with the Tuskegee men.

Germans also translated Washington’s Up from Slavery for teaching throughout Togo, as they appreciated his connection between work and uplift, chiding the Black church for upholding laziness.

Many of the graduates of these schools were then forced to become sharecroppers, taking the entire labor regime from the American South and imposing it upon Africans. Of course people hated it and wanted to leave.

But the Germans wouldn’t allow that, though of course people running away was not uncommon. Labor discipline would be had. So would Washington’s vision as he approved of all of this.

White supervisors from the American South were also brought over and used whippings as discipline in the schools.

In the end though, the Tuskegee project was only moderately successful and in order to engage in full-scale cotton plantations, the Germans had to rely on prisoners and those who had not paid their taxes to engage in forced labor.

In the end, this is perhaps the most shameful thing that Booker T. Washington was ever involved in.

The “uplift” that Washington and other Tuskegee leaders thought they were bringing to Africans was so deeply rooted in internalized racism from whites that they made their presence in Africa a true rot upon the people they intended to “help.”

I borrowed from Andrew Zimmerman, Alabama in Africa: Booker T. Washington, the German Empire, and the Globalization of the New South, published in 2010, to write this thread.

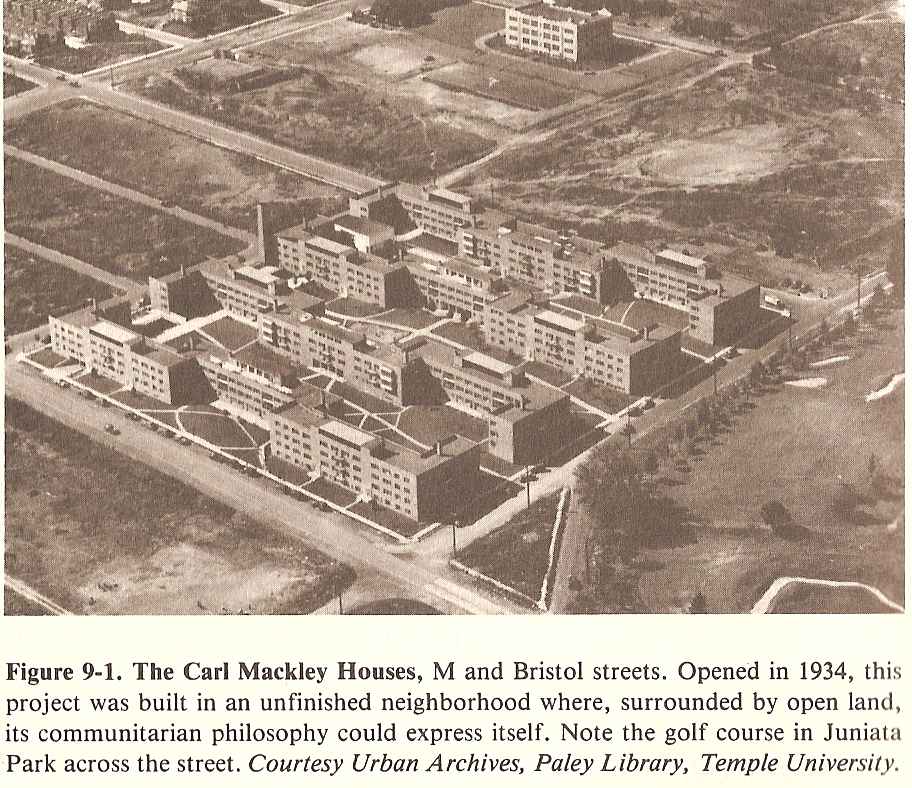

Back Friday for a discussion of union-based housing projects and the visions for a more expansive unionism in the 1930s.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh