1/ Lessons From The Tech Bubble:

Last year, I spent my winter holiday reading hundreds of pages of equity research from the 1999/2000 era, to try to understand what it was like investing during the bubble

A few people recently asked me for my takeaways. Here they are -

Last year, I spent my winter holiday reading hundreds of pages of equity research from the 1999/2000 era, to try to understand what it was like investing during the bubble

A few people recently asked me for my takeaways. Here they are -

2/ Every document hereon comes from my former employer Bernstein Research's internal research archive, which extend back to 1994

Unfortunately, they're not available to the public (even Bernstein's client website cuts off at 2003), but happy to give more details if necessary

Unfortunately, they're not available to the public (even Bernstein's client website cuts off at 2003), but happy to give more details if necessary

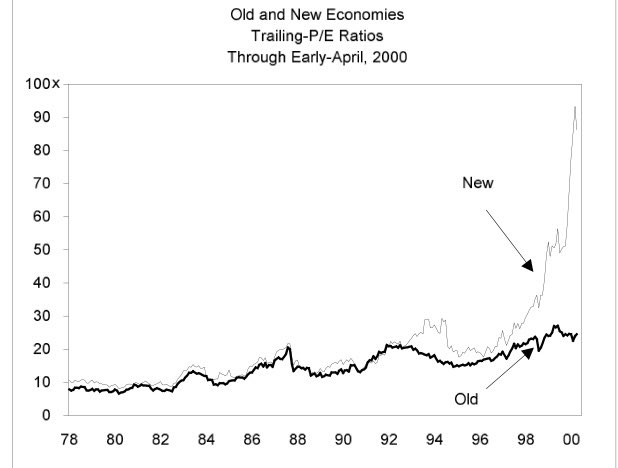

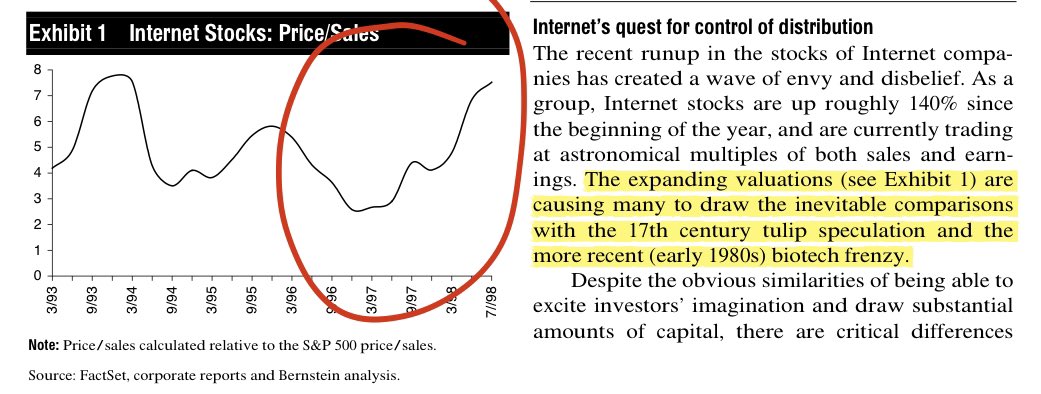

3/ LESSON #1: Everybody knew it was a bubble

Unfortunately, the quip "it's not a bubble if everyone says it is" just isn't true

Investors were comparing the internet sector to tulip mania as early as mid-98. Bernstein held an entire conference on it in June 99!

Unfortunately, the quip "it's not a bubble if everyone says it is" just isn't true

Investors were comparing the internet sector to tulip mania as early as mid-98. Bernstein held an entire conference on it in June 99!

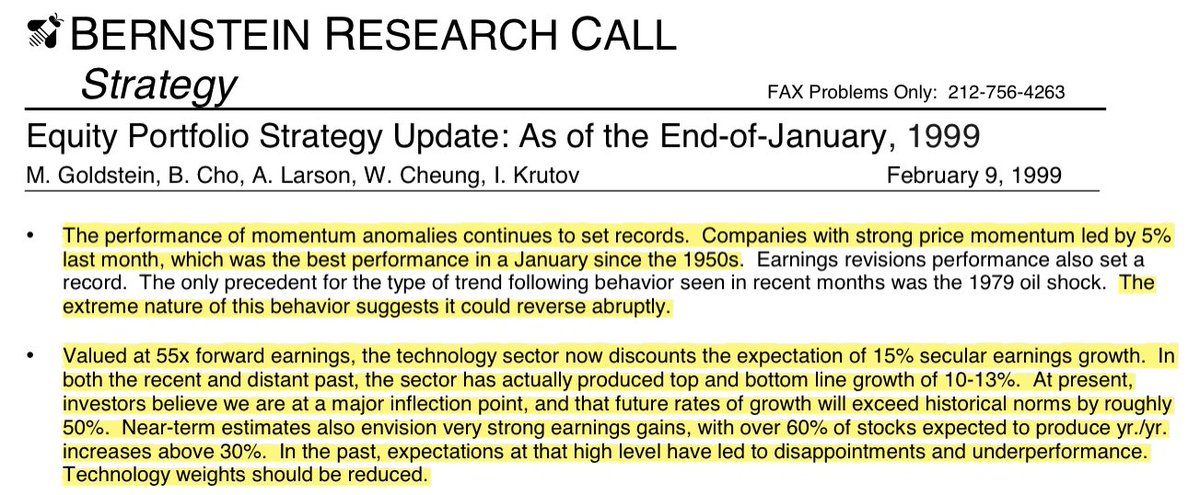

4/ LESSON #2: Calling bubbles is easy, making money is hard

In truth, the hard part about the tech bubble wasn't noticing it. The hard part was timing it

Our equity strategist tried in January 99... he was off by 14 months (and another 30 point gap in value vs growth)

In truth, the hard part about the tech bubble wasn't noticing it. The hard part was timing it

Our equity strategist tried in January 99... he was off by 14 months (and another 30 point gap in value vs growth)

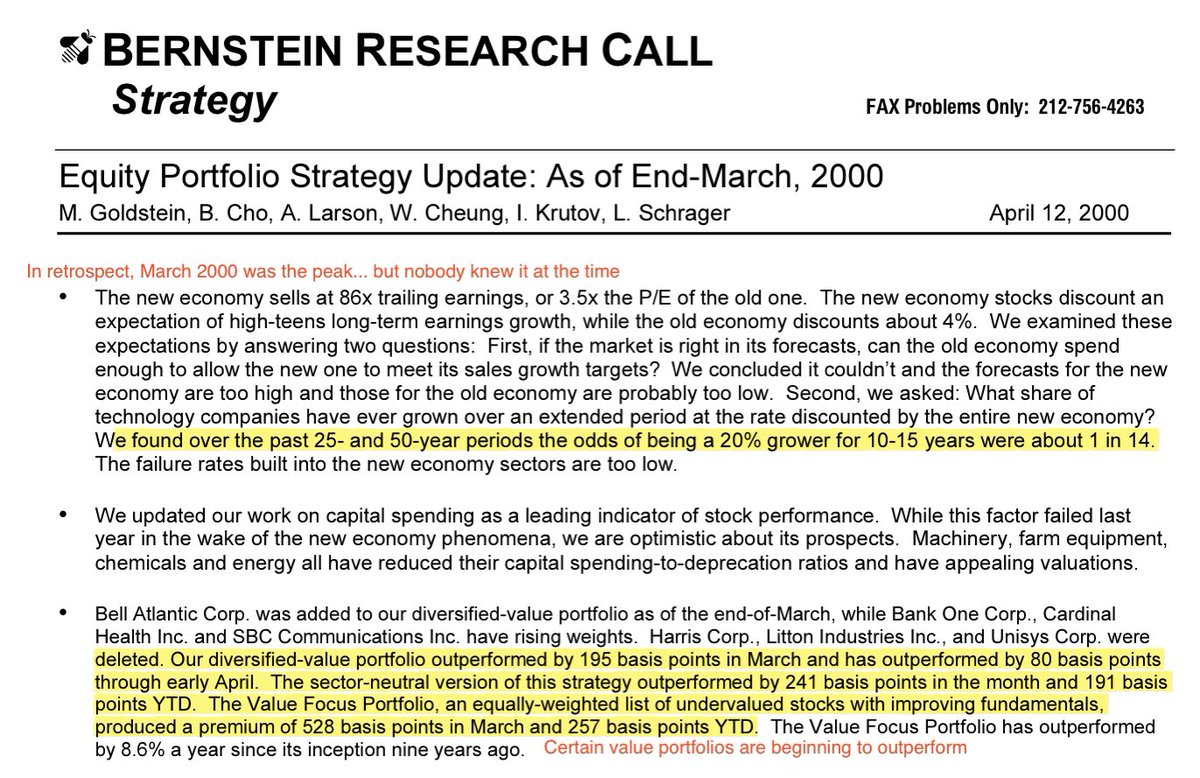

5/ LESSON #3: Nobody knew the bubble popped until months after it did

Nobody noticed in March 2000 when it finally popped. Our equity strategist (who bet his career on it!) didn't catch on until June

Nobody noticed in March 2000 when it finally popped. Our equity strategist (who bet his career on it!) didn't catch on until June

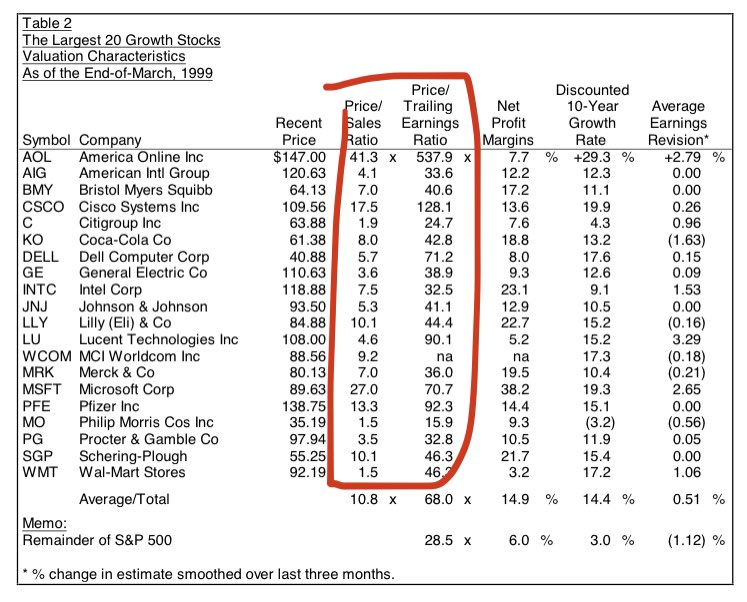

6/ LESSON #4: "Tech" bubble was a misnomer... it was really a large cap growth bubble

See the valuation table below, 1 year before the top

Yes, Microsoft traded at 70x earnings. But Coca Cola was 43x. Pfizer was 92x. Every stock here was a disaster over the next 10 years...

See the valuation table below, 1 year before the top

Yes, Microsoft traded at 70x earnings. But Coca Cola was 43x. Pfizer was 92x. Every stock here was a disaster over the next 10 years...

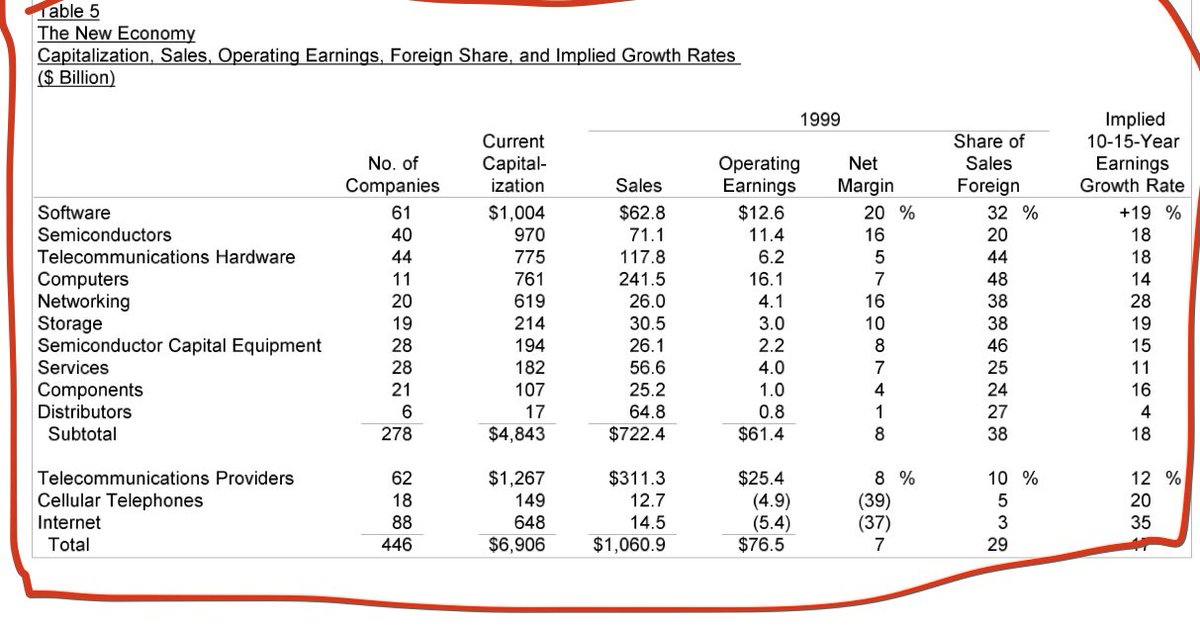

7/ LESSON #5: Most large cap tech stocks in the bubble had real businesses with strong fundamentals

The internet stocks were a sideshow. In 2000, the software sector had a $1 trillion market cap, 20% net margins, 20% annual growth

The problem? It was trading at 16x sales

The internet stocks were a sideshow. In 2000, the software sector had a $1 trillion market cap, 20% net margins, 20% annual growth

The problem? It was trading at 16x sales

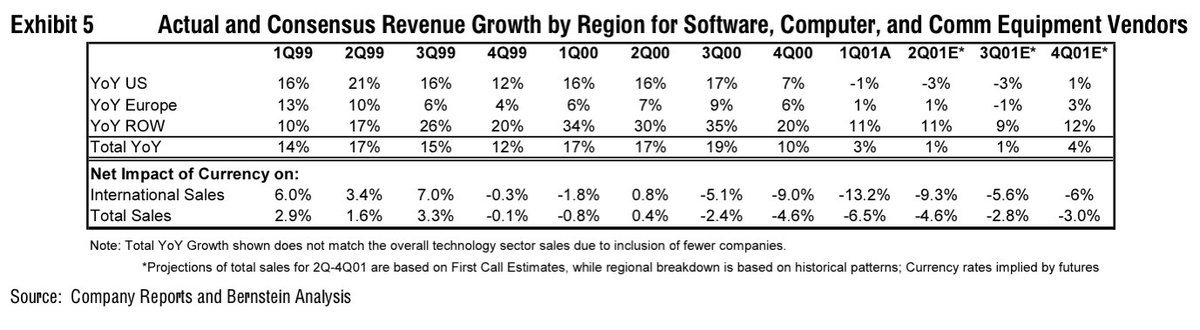

8/ LESSON #6: Fundamentals follow price, not vice versa

The bubble popped in Q1 2000. Fundamentals didn't decelerate until Q4 2000.

It was reflexivity at work. Lower stock prices = less capex spend = less revenue growth = lower stock prices. A vicious cycle

The bubble popped in Q1 2000. Fundamentals didn't decelerate until Q4 2000.

It was reflexivity at work. Lower stock prices = less capex spend = less revenue growth = lower stock prices. A vicious cycle

9/ What's the takeaway here?

Be humble.

For bears, it's easy to call a bubble. Anybody can do that. Timing is the hard part

For bulls, it's easy to point to the fundamentals. Historical investors weren't dumb. The hard part is matching fundamentals with price...

Be humble.

For bears, it's easy to call a bubble. Anybody can do that. Timing is the hard part

For bulls, it's easy to point to the fundamentals. Historical investors weren't dumb. The hard part is matching fundamentals with price...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh