In the NY Times today, I argue w/ @brianbeutler that a Civil War amendment to the Constitution--barring those who've "engaged in insurrection" from holding office--authorizes a broader response, one that goes beyond impeachment and beyond Trump alone.

nyti.ms/2MWMnE1

nyti.ms/2MWMnE1

Congress should use its power under the 14th Amendment to pass a law blocking the instigators and perpetrators of last week’s siege of the Capitol--including but not limited to Trump--from holding office ever again.

This would be a complement, not a substitute, for impeachment.

This would be a complement, not a substitute, for impeachment.

Even during the Civil War, the traitors never breached our Capitol. On Wednesday, they did. They paraded the Confederate battle flag through its halls, halted the electoral vote count, and upended the peaceful transfer of power with bloodshed.

nytimes.com/2021/01/09/us/…

nytimes.com/2021/01/09/us/…

As we respond, we should draw from the lessons of preceding generations--including those who drafted the Constitution's Fourteenth Amendment during what Reconstruction historian Eric Foner calls America's "Second Founding."

wwnorton.com/books/97803933…

wwnorton.com/books/97803933…

The Framers of the 14th Amendment arrived at a consensus that we sadly find ourselves needing to enforce again: Those who swear an oath to defend our Constitution but then betray that sacred oath by participating in an insurrection cannot be permitted to hold public office again.

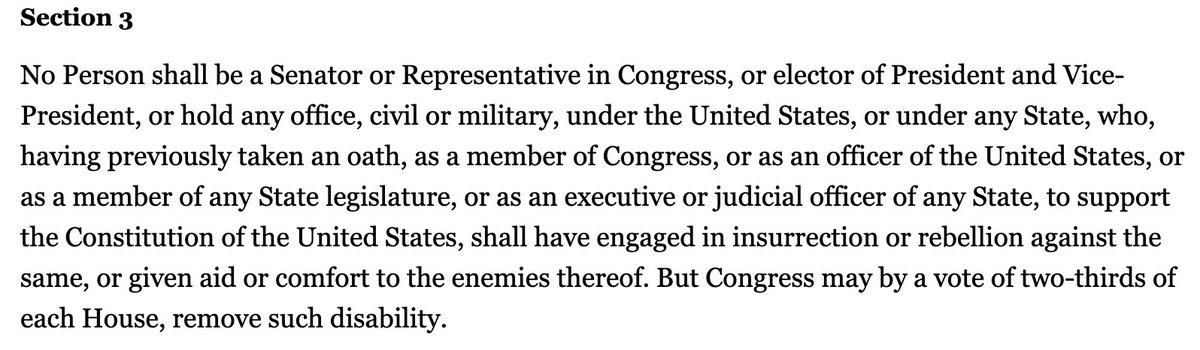

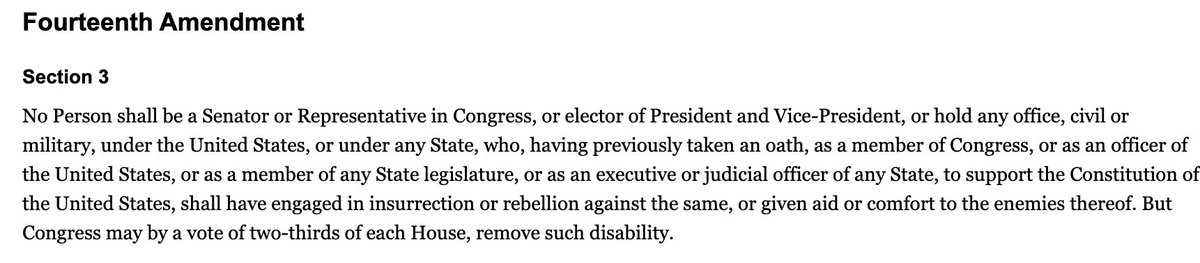

Section 3 of the 14th Amendment disqualifies anyone who, having sworn to defend the Constitution, has "engaged in insurrection or rebellion against [it]." And Section 5 gives Congress the "power to enforce" Section 3 "by appropriate legislation." Congress should invoke both.

But what counts as "insurrection or rebellion"? The answers can be found in historical legal understandings in English common law, the 14th Amendment's drafting history, and cases before and after the Civil War--including treason trials, like that of Jefferson Davis.

Some might believe that Section 3 only covers former Civil War Confederates. That's mistaken. The drafting history shows a switch to broader language. The drafters knew insurrections could happen again. And, years later, Congress recognized that "its provisions are for all time."

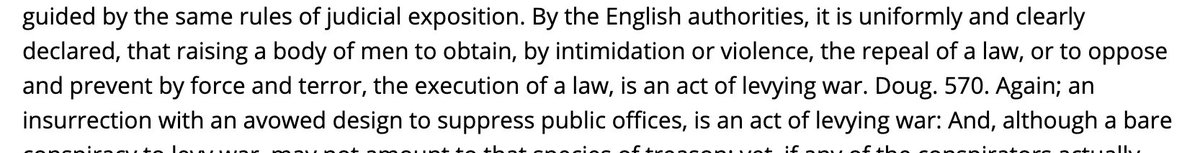

Dating back to 17th-century England, the law held that mobs that violently attacked and obstructed the legislature could be prosecuted for “treason by levying war” against the state—a historical origin of the Fourteenth Amendment’s reference to “insurrection or rebellion.”

When a mob obstructs and impedes the enforcement of the law and civil authority, and specifically, when it (a) stops a legislature from performing its constitutional functions and (b) causes violence requiring the civil authorities to call in the military, that's an insurrection.

"[R]aising a body of men to obtain, by intimidation or violence, the repeal of a law, or to oppose and prevent by force and terror, the execution of a law, is an act of levying war." US v Mitchell, 2 U.S. 348 (C.C.D. Pa. 1795)

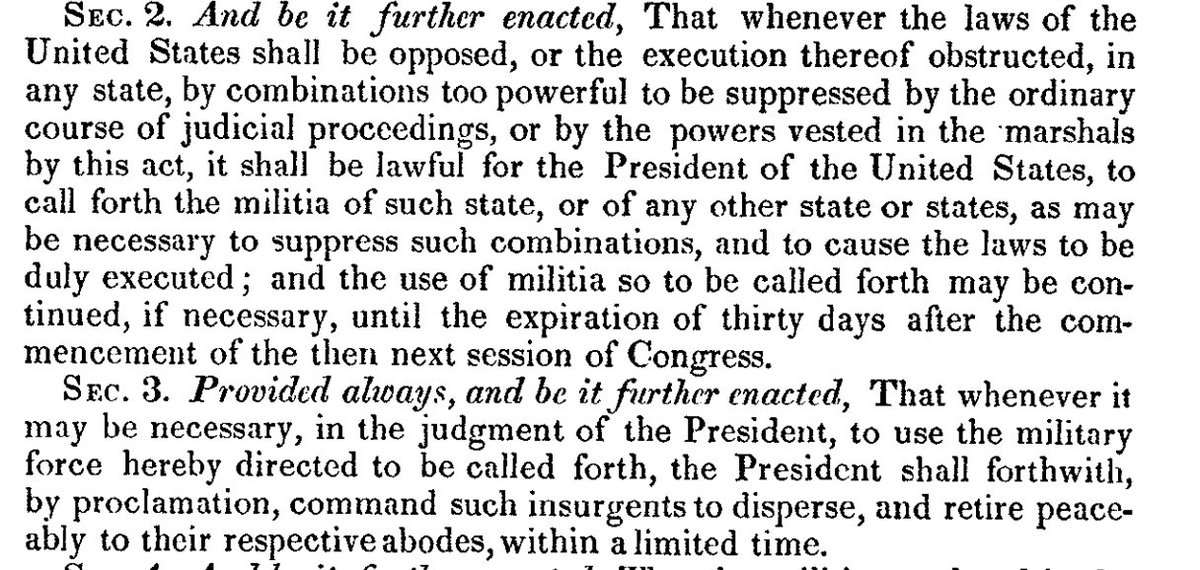

Under the Militia Act of 1795, the Insurrection Act's predecessor, it's when "the laws of the United States shall be opposed or the execution thereof obstructed by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings." bit.ly/3oE0N9X

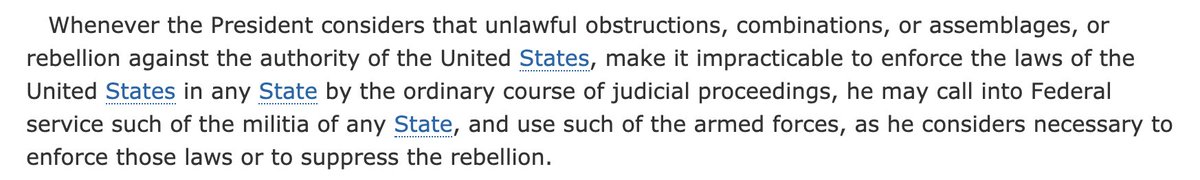

The Insurrection Act likewise applies where "unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in any State by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings."

By now, you get the idea. What happened last week was a textbook insurrection. The mob attacked Congress to stop the constitutional process of counting of votes. For a time, the mob succeeded. The National Guard had to be called in to quell the violence and secure the Capitol.

What about "engaging in" insurrection? Professor Feldman speculates that incitement might not be enough. But courts, scholars, & prosecutors have long recognized that one who incites an insurrection is an insurgent—even if they don't personally take up arms or carry out violence.

Does an insurrection require a presidential proclamation? No. It’s true that the Militia & Insurrection Acts contemplate a proclamation ordering "the insurgents to disperse.” But that's not what *defines* an insurrection--that's a procedural precondition for federal intervention.

That Section 3’s “insurrection or rebellion” language can’t be reasonably read to require a proclamation is also clear from historical treason cases, in which people are found guilty of engaging in the equivalent of insurrection without any proclamation to that effect.

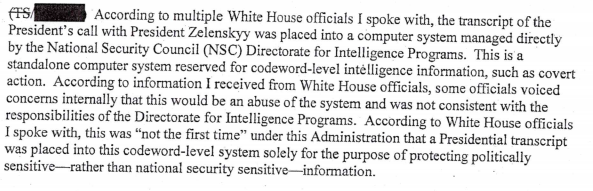

And, here, it would be stranger than strange to deny that there was an insurrection last Wednesday because the President didn't issue a proclamation of insurrection: Shamefully, it was President Trump himself who was our Inciter-in-Chief.

Some might also raise objections based on the prohibitions on bills of attainder & ex-post-facto laws. But legislation needn’t identify Trump (or anyone) by name. It can declare that January 6 was an insurrection & create a process and standards to be applied based on the facts.

Legislation along these lines has benefits that impeachment can't provide. It may extend later to members of Congress, current & former law enforcement or military, and others who are discovered on investigation to have actively incited, directed, or carried out the insurrection.

Congress can also simultaneously pass non-binding sense-of-Congress resolutions to further guide courts, election administrators, and others in carrying out its legislation. Courts will likely defer to Congress's findings, while observing due process.

Why legislation? Isn't the Constitution self-enforcing? Litigation under Section 3 may be inevitable. But legislation via Section 5 can create a cause of action, standards of conduct, procedures, and instructions on weighing evidence--putting enforcement on a far surer footing.

Why is this a complement to impeachment? Impeachment demands a full Senate trial now. But a law can be applied over time, based on all facts developed, sweeping in others who incited or directed the mob: members of Congress, current or former military or law enforcement.

Caveat emptor: These are just a few preliminary thoughts on a novel set of legal and prudential issues. Getting this all right will require further research, analysis, and deliberation.

In the days just before Trump's inauguration, I was surprised to find myself focused on the constitutional meaning of "emoluments." In his final days, I'm shocked to find myself contemplating the constitutional meaning of "insurrection or rebellion."

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh