It's often said that the indigenous people of South America never developed a system of writing.

But this isn't entirely true. In fact, they created a unique and complex system of notation based on the tying of knots, known as quipu, which remain undeciphered to this day.

But this isn't entirely true. In fact, they created a unique and complex system of notation based on the tying of knots, known as quipu, which remain undeciphered to this day.

The quipu were usually made from string, spun from cotton fibers, or the fleece of camelid animals like the alpaca and llama.

The cords stored information with knots tied in vast assemblages of string, sometimes containing thousands of threads.

The cords stored information with knots tied in vast assemblages of string, sometimes containing thousands of threads.

In some analysed quipu, the combinations of thread length, colour, knot type and knot position allow for up to 95 possible combinations, which could represent numbers, symbols or even sounds.

The Inca people used them for collecting data and keeping records, monitoring taxes, conducting censuses, keeping track of dates, and for military organization, all with immense success.

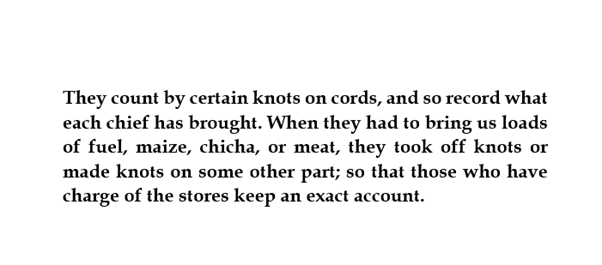

One early European eyewitness Hernando Pizarro records one early sighting of these quipu.

One early European eyewitness Hernando Pizarro records one early sighting of these quipu.

In fact, these quipu were the only system of notation used to administrate the Incas’ society, a vast stretch of land the same size as the Western Roman empire in Europe, containing more than 10 million people – all of which operated without a single word being written down.

But since the collapse of Inca society, the knowledge of how exactly how to read the quipu has been lost.

They were once interpreted by a class of learned people known as quipucamayocs, who were trained in their art in Inca schools or yachay wasi (literally "house of teaching").

They were once interpreted by a class of learned people known as quipucamayocs, who were trained in their art in Inca schools or yachay wasi (literally "house of teaching").

Quipucamayocs were usually drawn from the children of the ruling class.

The quipu were read with the hands, and according to Quechuan chronicler Guaman Poma, quipucamayocs could even read the quipus with their eyes closed.

The quipu were read with the hands, and according to Quechuan chronicler Guaman Poma, quipucamayocs could even read the quipus with their eyes closed.

There is a great deal of debate about how much information these quipu actually encoded.

One thing we are fairly certain of: the quipu mainly contained numerical information.

One thing we are fairly certain of: the quipu mainly contained numerical information.

This information was crucial for running the Incas' highly controlled and centralised economy.

The quipu would have recorded the numbers of people in a certain province, the amount of food needed, the amount of cloth produced, the amount of recruits, etc. archive.org/details/lastof…

The quipu would have recorded the numbers of people in a certain province, the amount of food needed, the amount of cloth produced, the amount of recruits, etc. archive.org/details/lastof…

We can identify this numerical information because researchers have been able to point to elements on the knots that conduct arithmetic in a systematic way.

For instance, one cord may contain the sum of the next certain amount of cords, with this relationship being repeated throughout the quipu. And in many quipu, there is a clear system of decimals at work.

But more controversial is the question of whether the quipu could also contain messages, or even the literature of the Inca.

One Jesuit priest named Joseph de Acosta is quite clear in his accounts that the quipu were more than just counting devices.

One Jesuit priest named Joseph de Acosta is quite clear in his accounts that the quipu were more than just counting devices.

As far as we can tell, the quipu knots don’t follow the structure of any known indigenous Peruvian language, and so it has long been believed that they don’t hold phonetic information – that is, they don’t encode sounds like our alphabet does.

However, others have suggested that the knots might encode binary information that could be interpreted to create sounds.

Gary Urton The Khipu Database Project (KDP) claims to have already decoded the first word from a quipu – the name of the village of Puruchuco (pictured).

Gary Urton The Khipu Database Project (KDP) claims to have already decoded the first word from a quipu – the name of the village of Puruchuco (pictured).

Urton believes that this name was represented by a three-number sequence, similar to a postal code.

If this hypothesis is correct, then the quipu are the only known example of a complex language recorded in a three-dimensional system.

If this hypothesis is correct, then the quipu are the only known example of a complex language recorded in a three-dimensional system.

One study led by Alberto Sáez-Rodríguez has even claimed to show that the distribution and patterning of S- and Z-knots can organize the information system from a real star map of the Pleiades cluster.

Source: researchgate.net/publication/27…

Source: researchgate.net/publication/27…

If the quipu do contain writing, and could be decoded, then it would be an immensely significant discovery.

No example of written Quechua has been found before the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century, and all our knowledge of Andean culture comes from later sources.

No example of written Quechua has been found before the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century, and all our knowledge of Andean culture comes from later sources.

But the quipu we have are only a fraction of what once existed. Soon after their conquest of Peru, Spanish authorities quickly suppressed the use of quipus.

Quipu were often used to record offerings to Inca gods, and were therefore considered idolatrous objects.

Quipu were often used to record offerings to Inca gods, and were therefore considered idolatrous objects.

Christian officials of the Third Council of Lima banned the system, and in 1583 ordered that all quipu discovered should be burned.

We do not know the total number of quipu burned, or what information may have been contained within them.

We do not know the total number of quipu burned, or what information may have been contained within them.

We can hope that perhaps one day a breakthrough in the interpretation of the surviving quipu will allow them to speak once more.

But for now, they stand as a silent testimony to the fragility of human culture, and how easily the connections of memory and history can be severed.

But for now, they stand as a silent testimony to the fragility of human culture, and how easily the connections of memory and history can be severed.

Further reading:

“The Quipu: ‘Written’ Texts in Ancient Peru.” Elizabeth P. Benson. jstor.org/stable/2640394…

“The last of the Incas : the rise and fall of an American empire” by Edward Hyams. archive.org/details/lastof…

“The Quipu: ‘Written’ Texts in Ancient Peru.” Elizabeth P. Benson. jstor.org/stable/2640394…

“The last of the Incas : the rise and fall of an American empire” by Edward Hyams. archive.org/details/lastof…

If you enjoyed this thread, you can find out more about the rise and fall of Inca society in the new episode of Fall of Civilizations.

Listen here, or on any podcasting app.

Spotify: open.spotify.com/episode/3Nqbrj…

YouTube:

Listen here, or on any podcasting app.

Spotify: open.spotify.com/episode/3Nqbrj…

YouTube:

You might also enjoy this thread on the only true writing system of the Americas - Mayan hieroglyphs.

https://twitter.com/Fall_of_Civ_Pod/status/1067392784225763328

You can also support the show here: patreon.com/fallofciviliza…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh