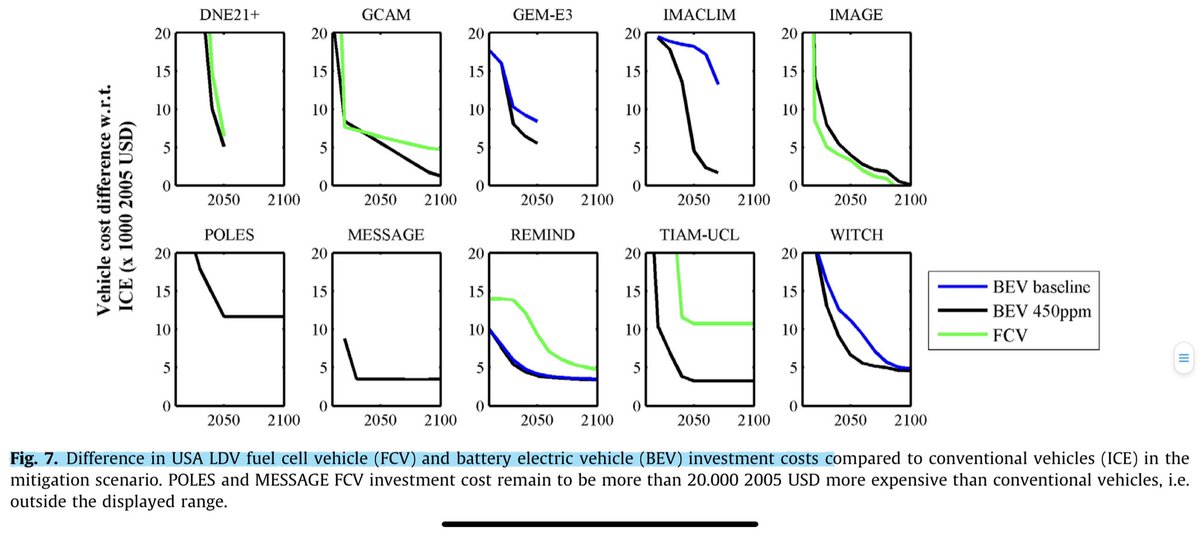

Wow - many popular climate models have been assuming electric vehicles will remain more expensive than internal combustion engine cars all the way to 2100. As a modeler, I sympathize cost assumptions are hard but there’s a lot of room for improvement here. sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

At current battery cost trends, EVs will reach cost parity with ICE in years, not decades or centuries as in these models (see thread below). E.g. BNEF projects cost parity in 2023. These are order of magnitude differences between bottom-up forecasting and climate modeling!

https://twitter.com/emildimanchev/status/1310591016630734849

To those tracking clean energy cost projections, this is probably not surprising, @AukeHoekstra, @MLiebreich. To me it’s raising the following question - is modeling research really not learning to model new technologies better after the ignoble experiences with solar and wind?

From experience in labs working on such modeling, I know that climate-economy modelers work hard to account for trends in clean energy technologies, and yes, the future is uncertain. But this is showing that modeling needs to do better yet.

And note how EV costs do not fall with climate policy (blue and black lines are the same) in most models, which is basically saying the models are not self-consistent (since climate action is not driving additional cost improvements though in reality it would).

On the bright side, this means that 1) we can reduce emissions from transportation further and/or at a lower cost than models have previously told us and 2) the potential for EVs is greater than indicated in such modeling.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh