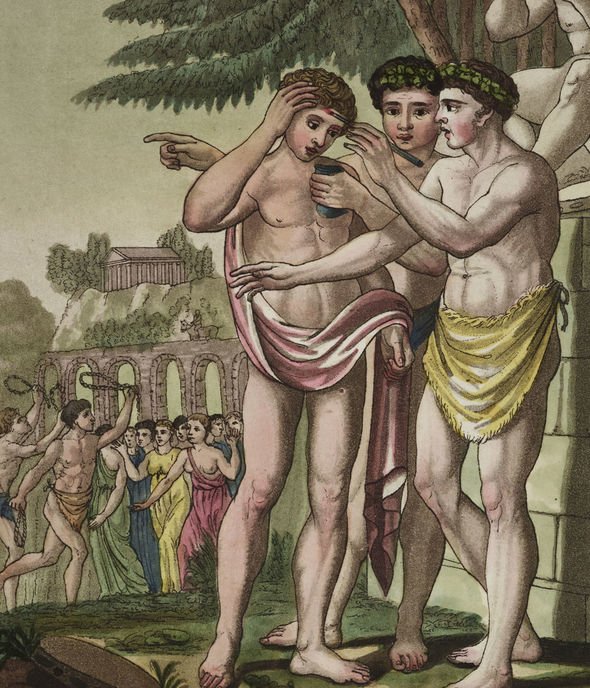

The history of the St. Valentine’s Day celebrations appears to have its roots in a pagan fertility festival known as Lupercalia.

Celebrated in ancient Rome between 13 – 15 February, the festival is said to have involved lots of naked folk running through the streets spanking the backsides of young women with leather whips, supposedly to improve their fertility.

Like many of the old pagan festivals, the early Christian Church appears to have highjacked the celebrations, sanitised and then reissued them with a certain amount of shall we say ‘spin’.

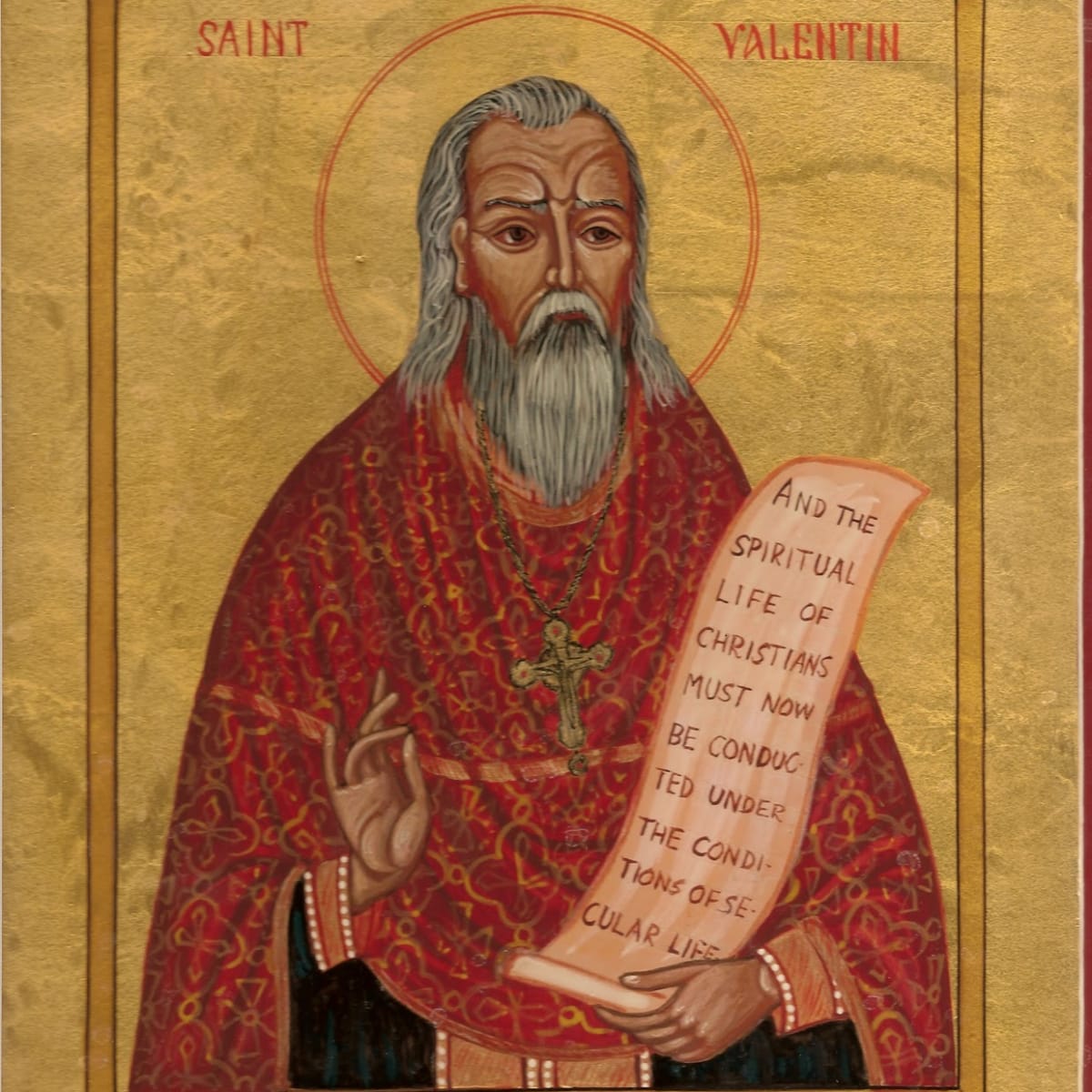

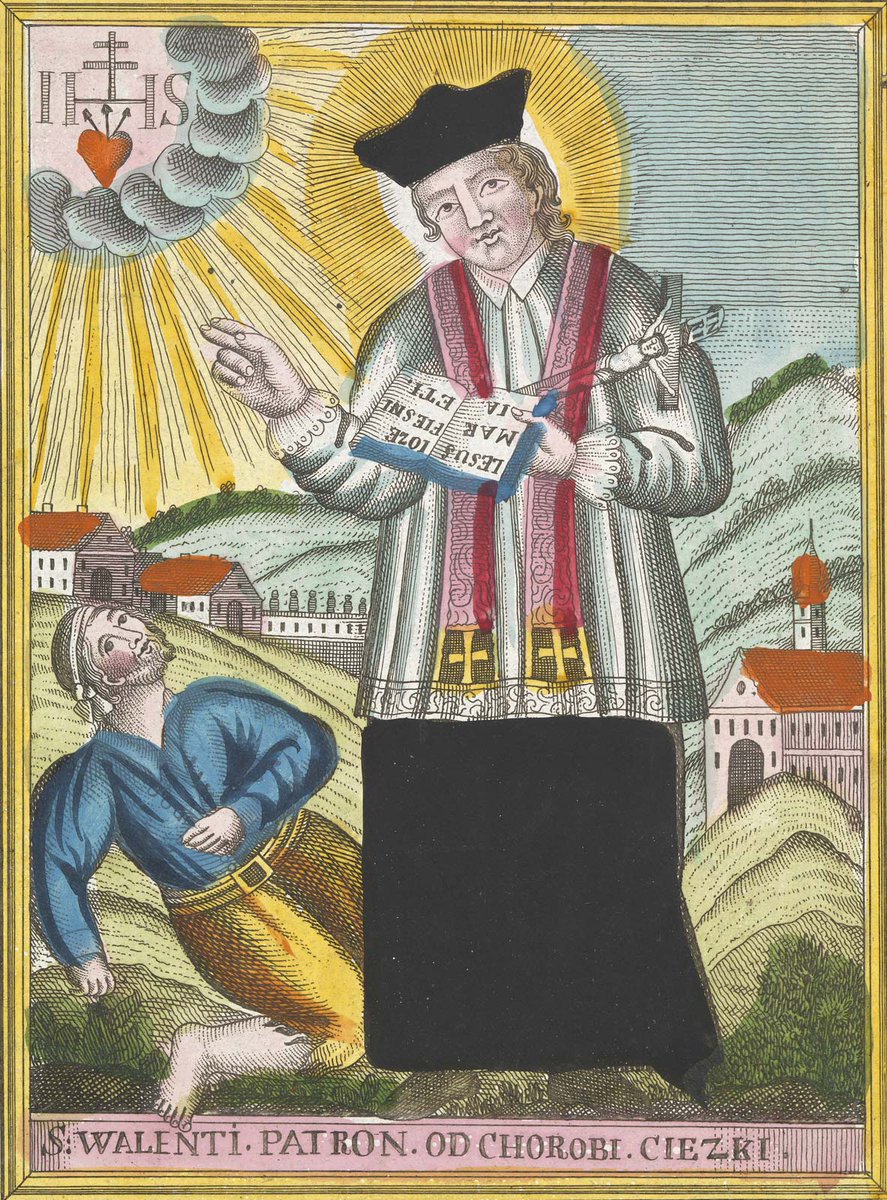

In the two centuries that followed the death of Christ, at least two separate accounts record how early Christian martyrs, all apparently called Valentine (or, in latin Valentinus), met with their ends on 14th February.

In 496 AD, Pope Gelasius appears to have come clean by formally declaring the 14th February to be St. Valentine’s Day, now rebranded as a Christian feast day!

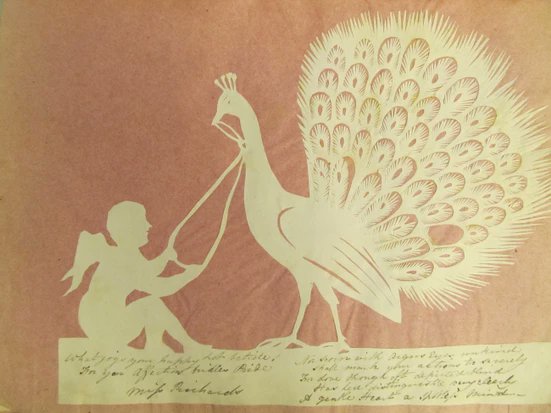

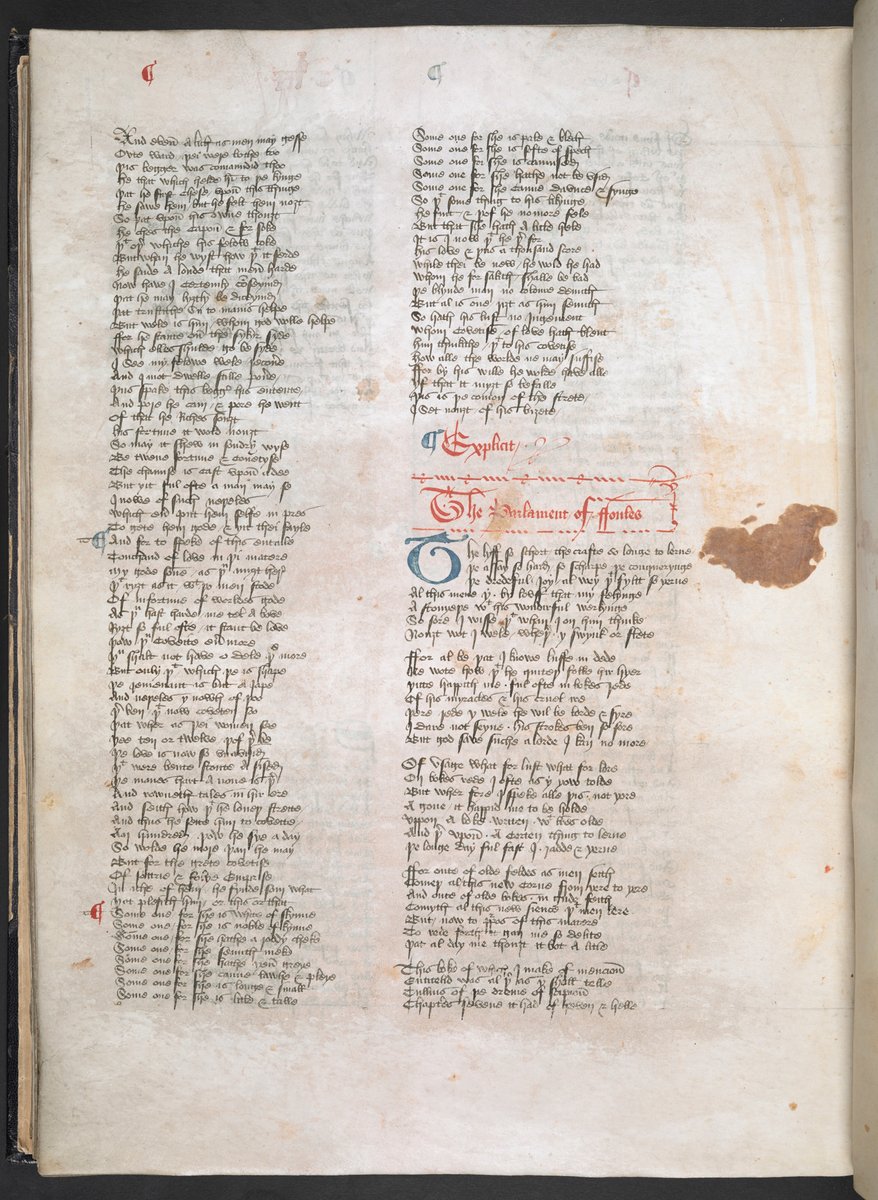

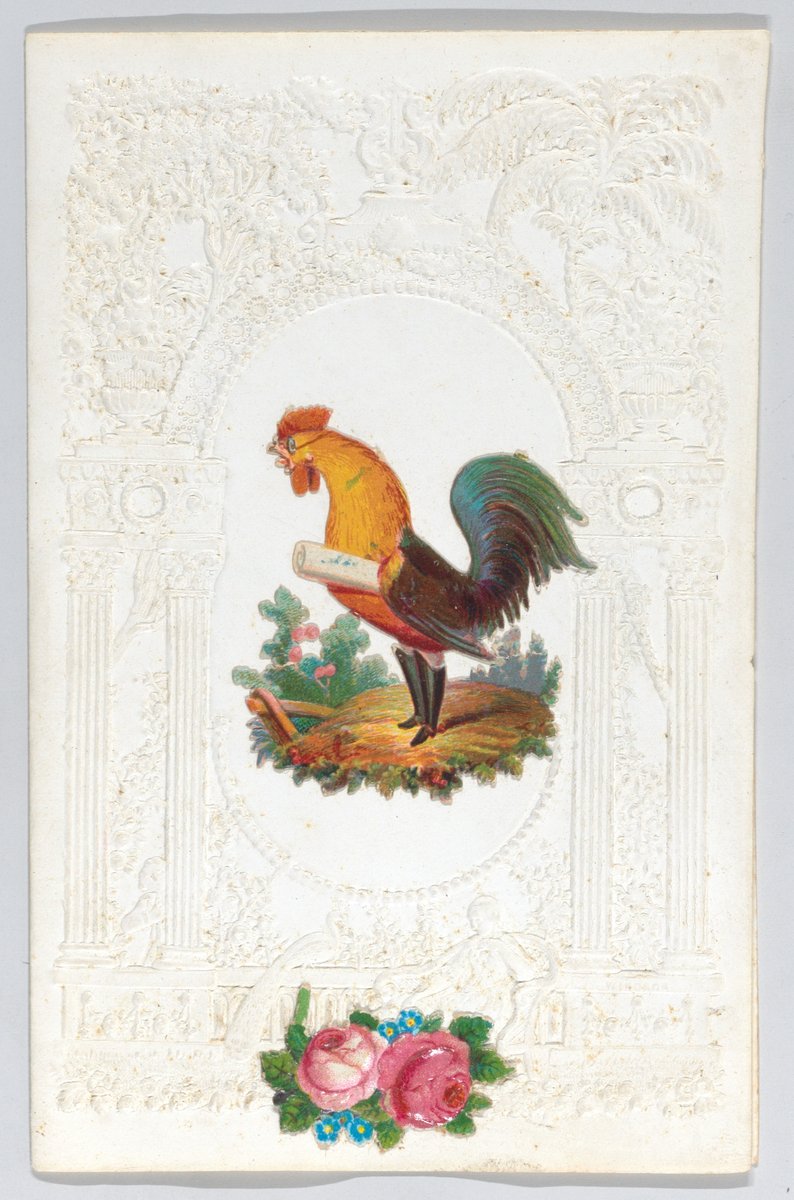

The first real association of St. Valentine’s Day with romantic love, or ‘love birds’, derives from Geoffrey Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules (or, ‘Parliament of Fowls’).

Dating from 1382, Chaucer celebrated the engagement of the 15 year-old King Richard II to Anne of Bohemia via a poem, in which he wrote: For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird (fowl) cometh to choose his mate.

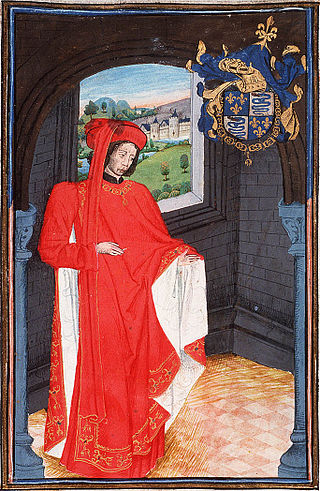

True to form though, it was a Frenchman who is recorded as sending the earliest surviving Valentine’s note to his sweetheart. Charles, the Duke of Orléans, was writing to her from his prison cell in the Tower of London following his capture at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.

By 1601 St. Valentine’s Day appears to be an established part of English tradition, as William Shakespeare makes mention of it in Ophelia’s lament in Hamlet: To-morrow is Saint Valentine’s day, All in the morning betime, And I a maid at your window, To be your Valentine.

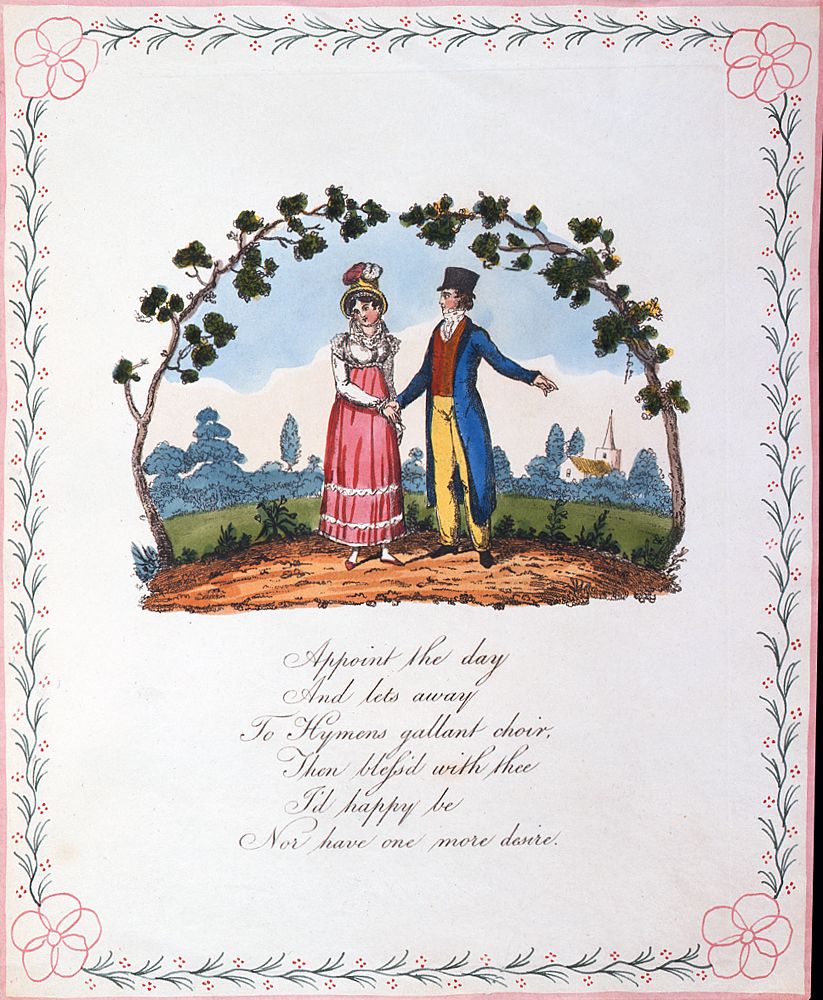

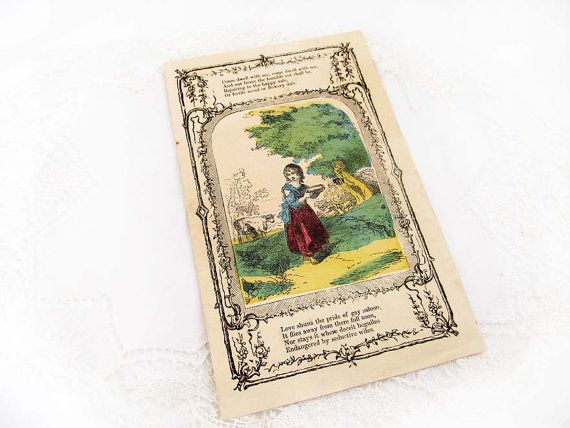

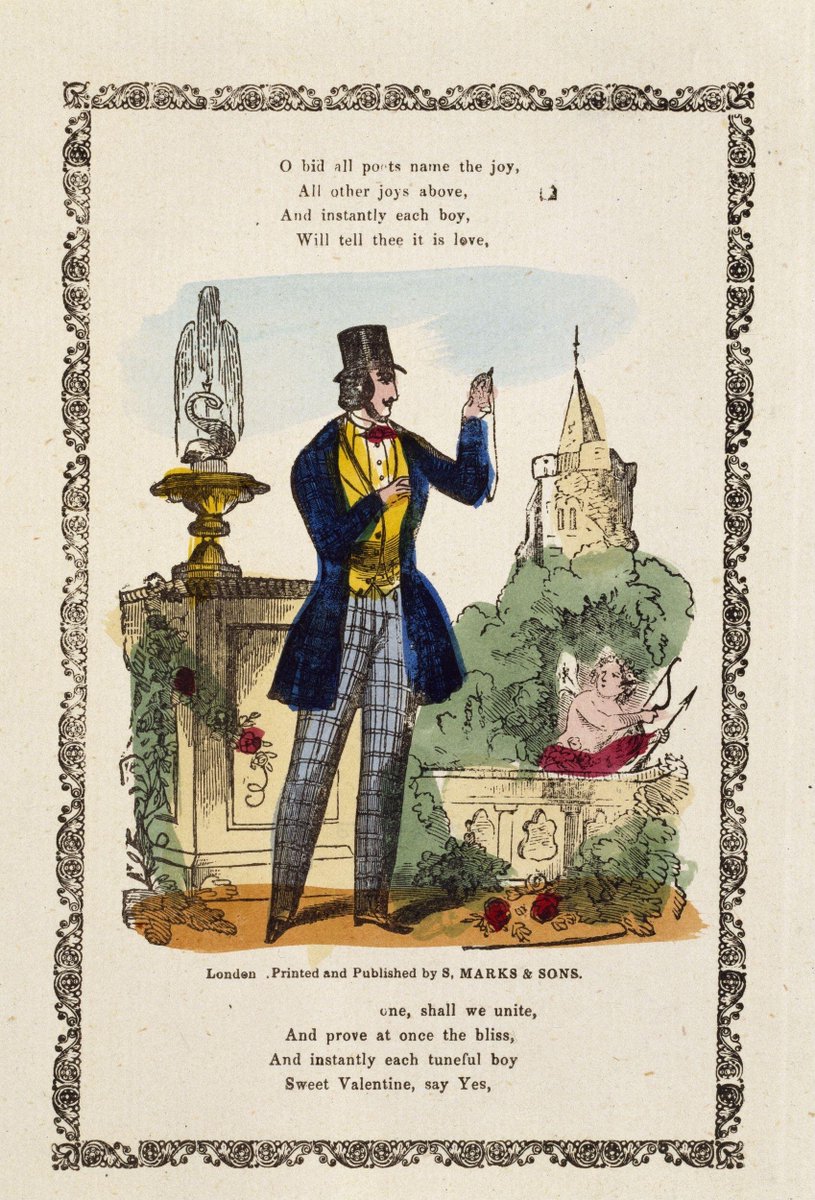

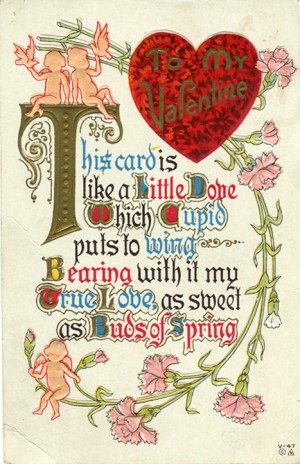

The passing of love-notes between sweethearts appears to have become standard practice, as in 1797, The Young Man’s Valentine Writer was first published.

This contained gems of sentimental rhymes and ditties for those young gentlemen who were obviously so much in love as to not be able to think clearly enough to compose their own verse.

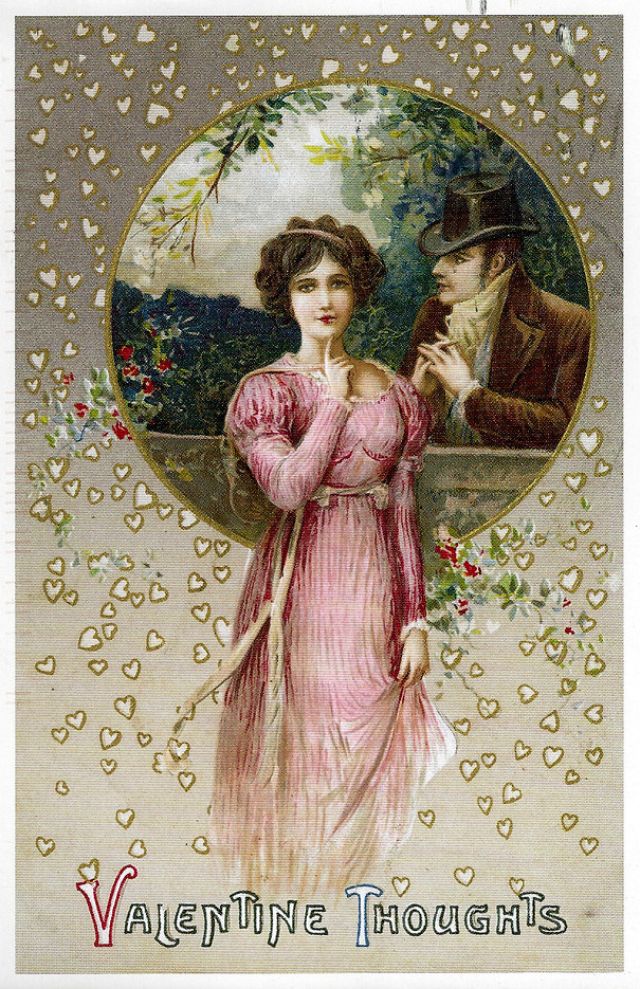

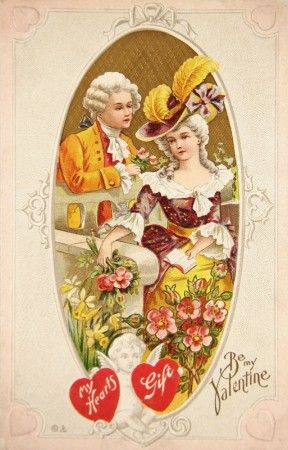

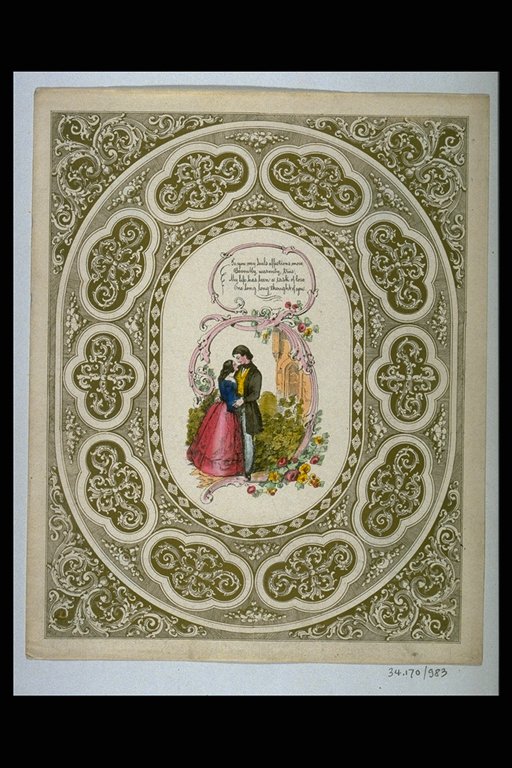

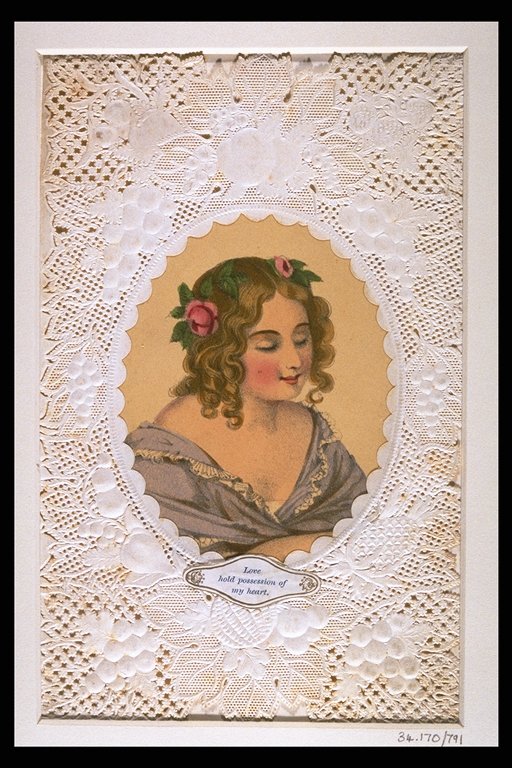

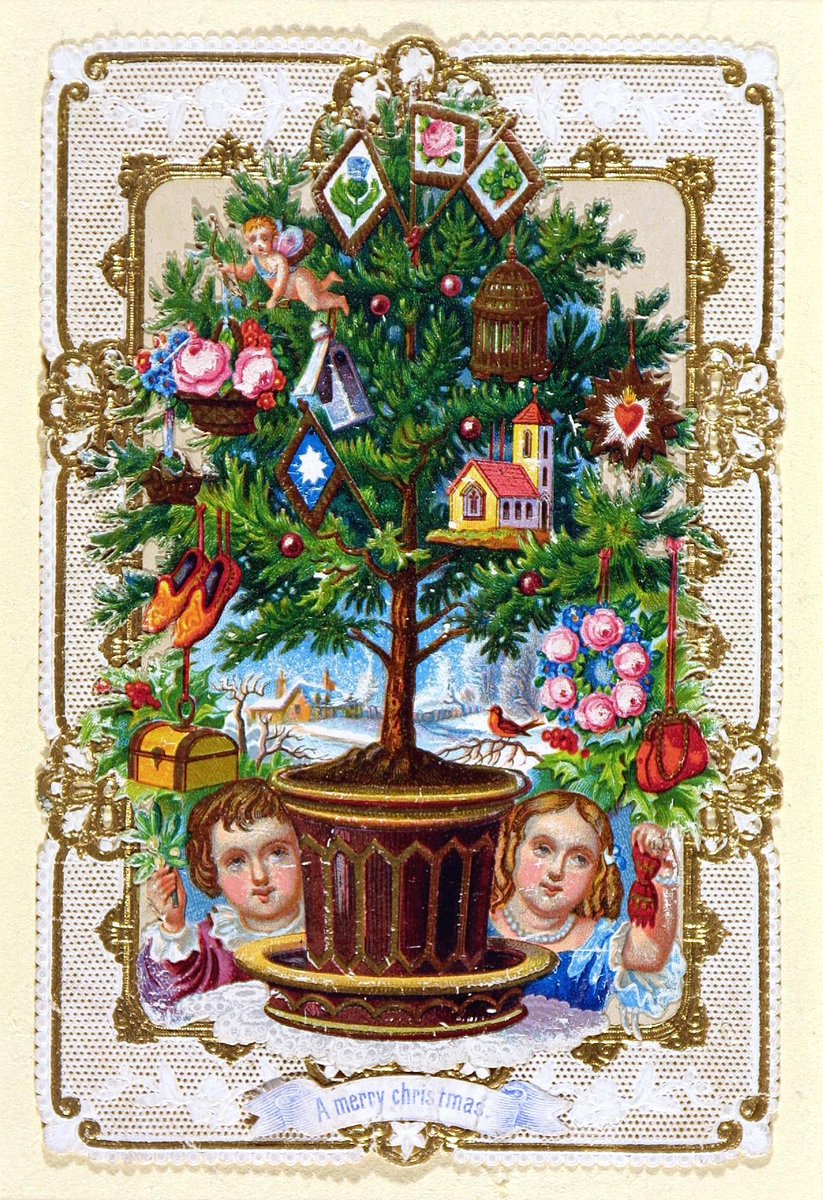

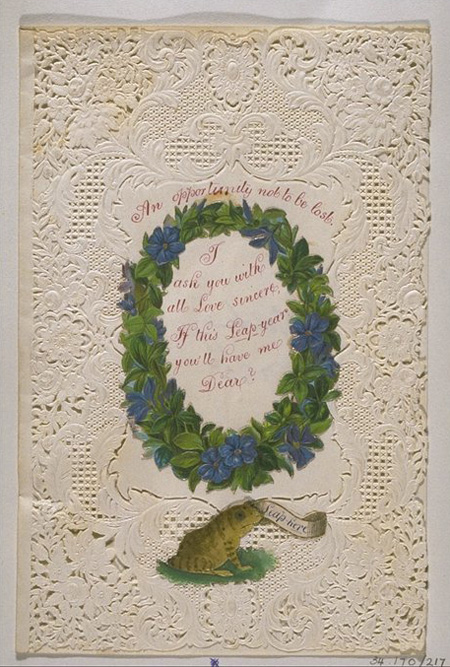

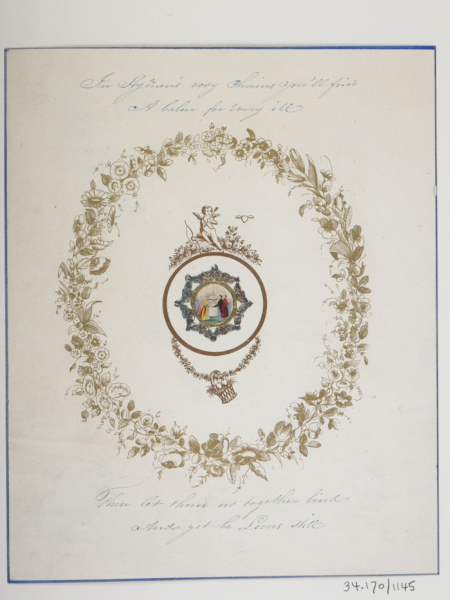

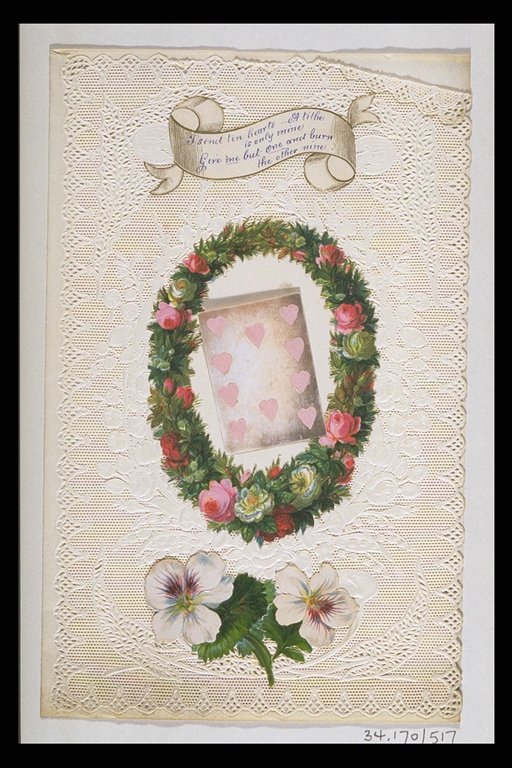

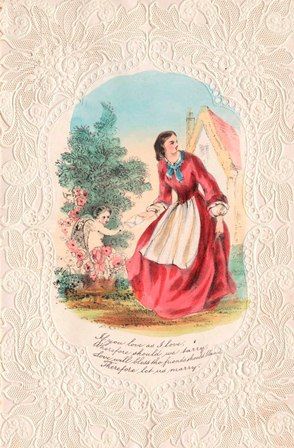

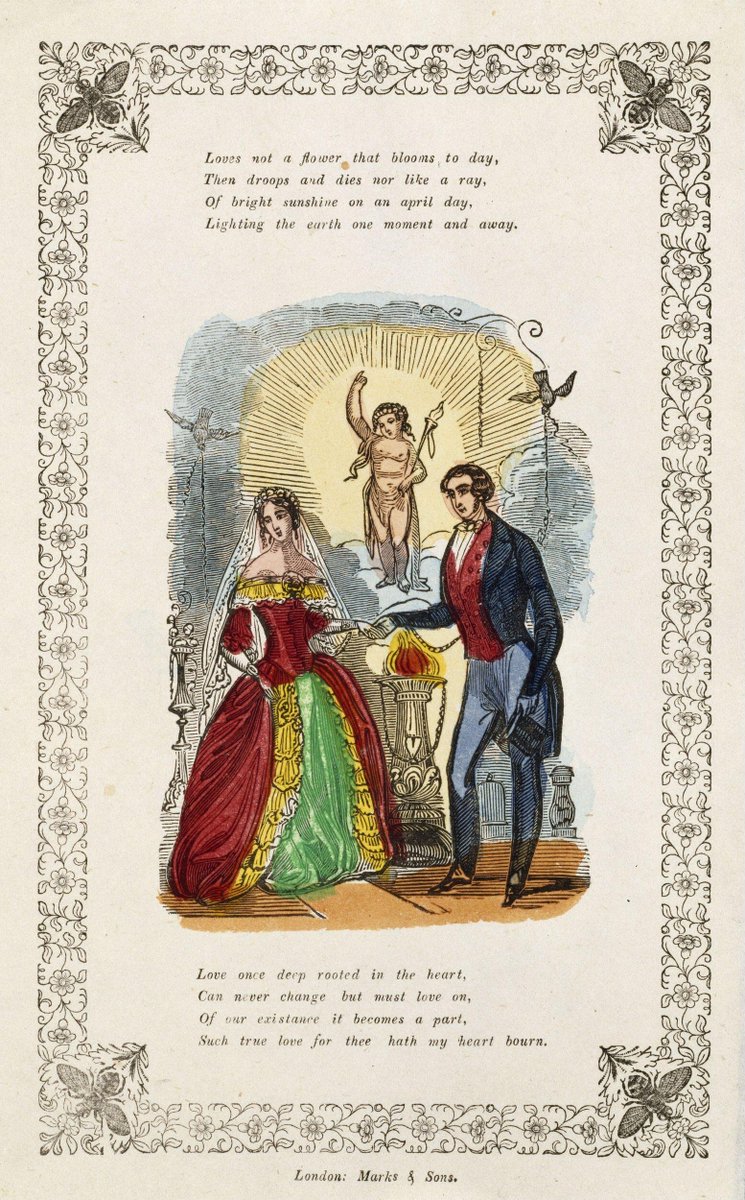

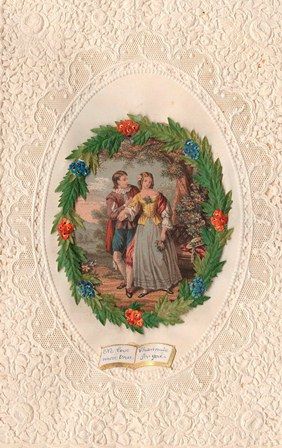

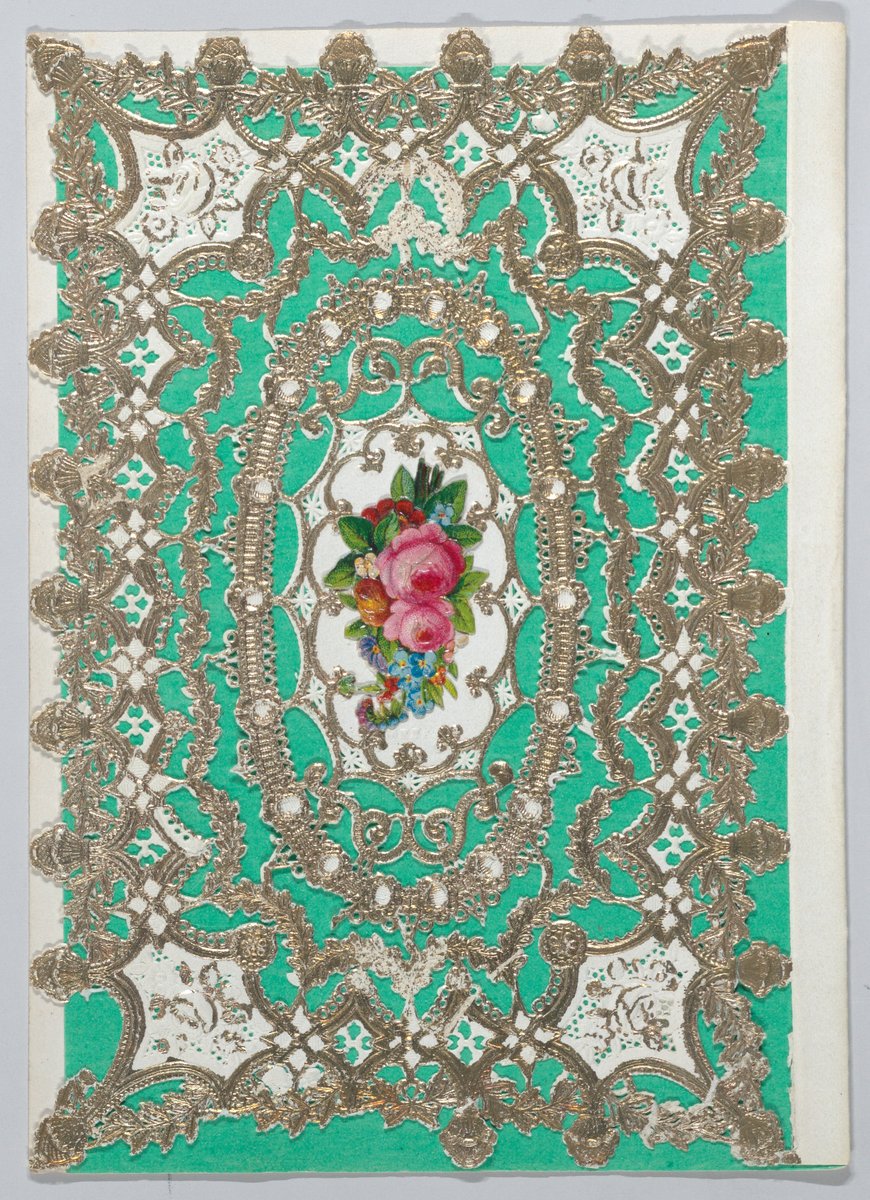

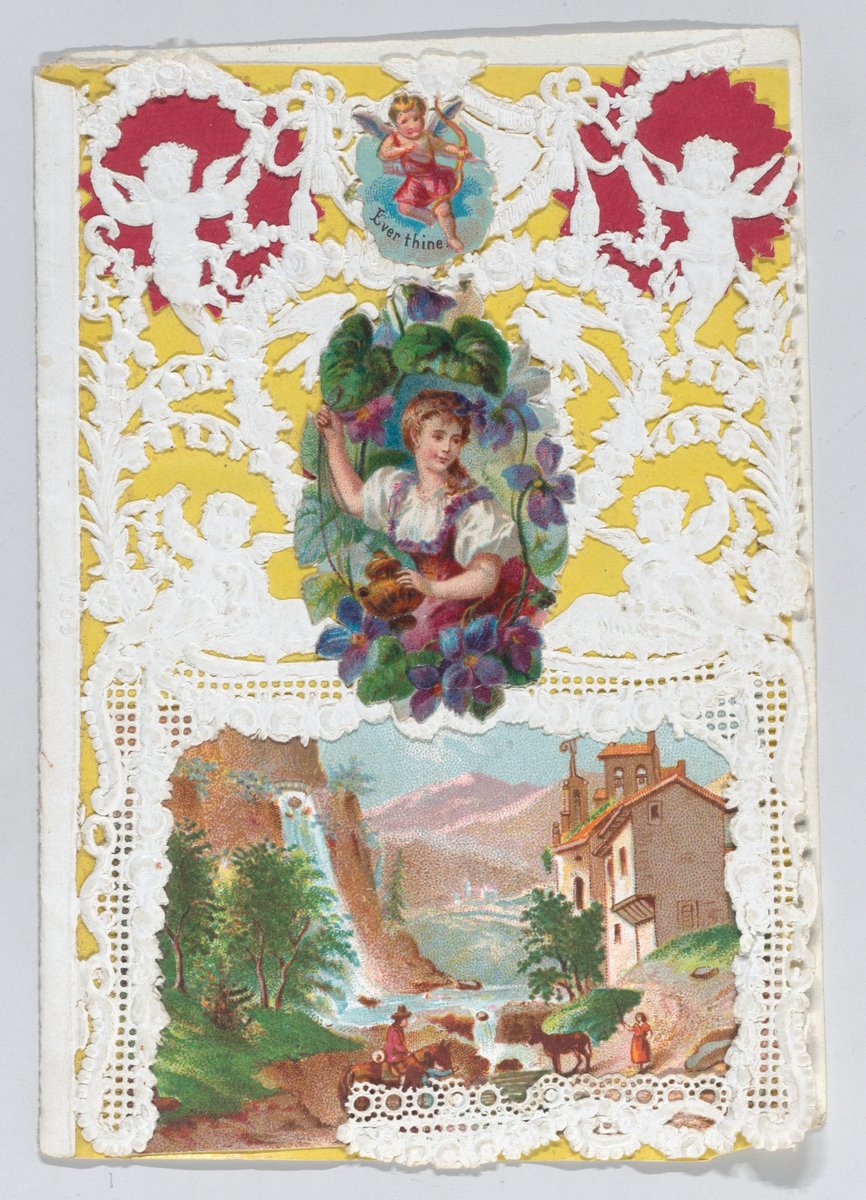

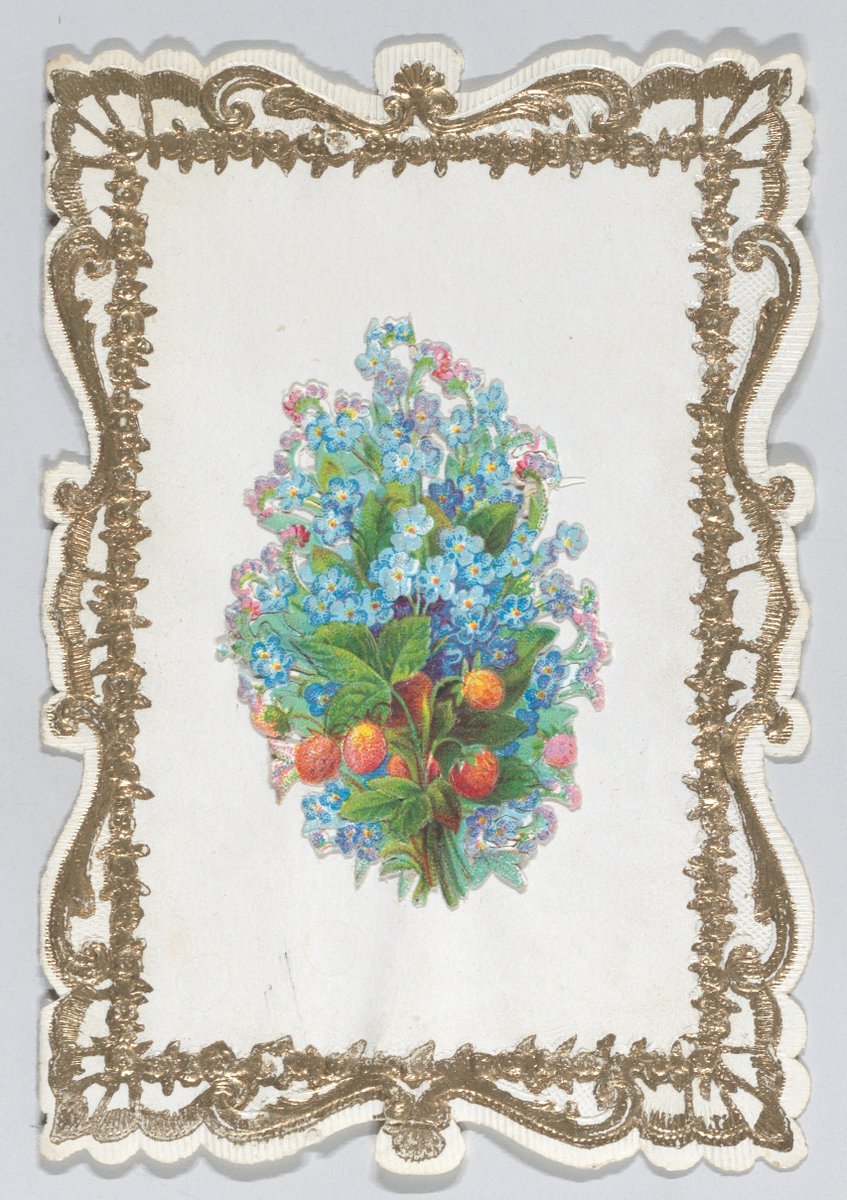

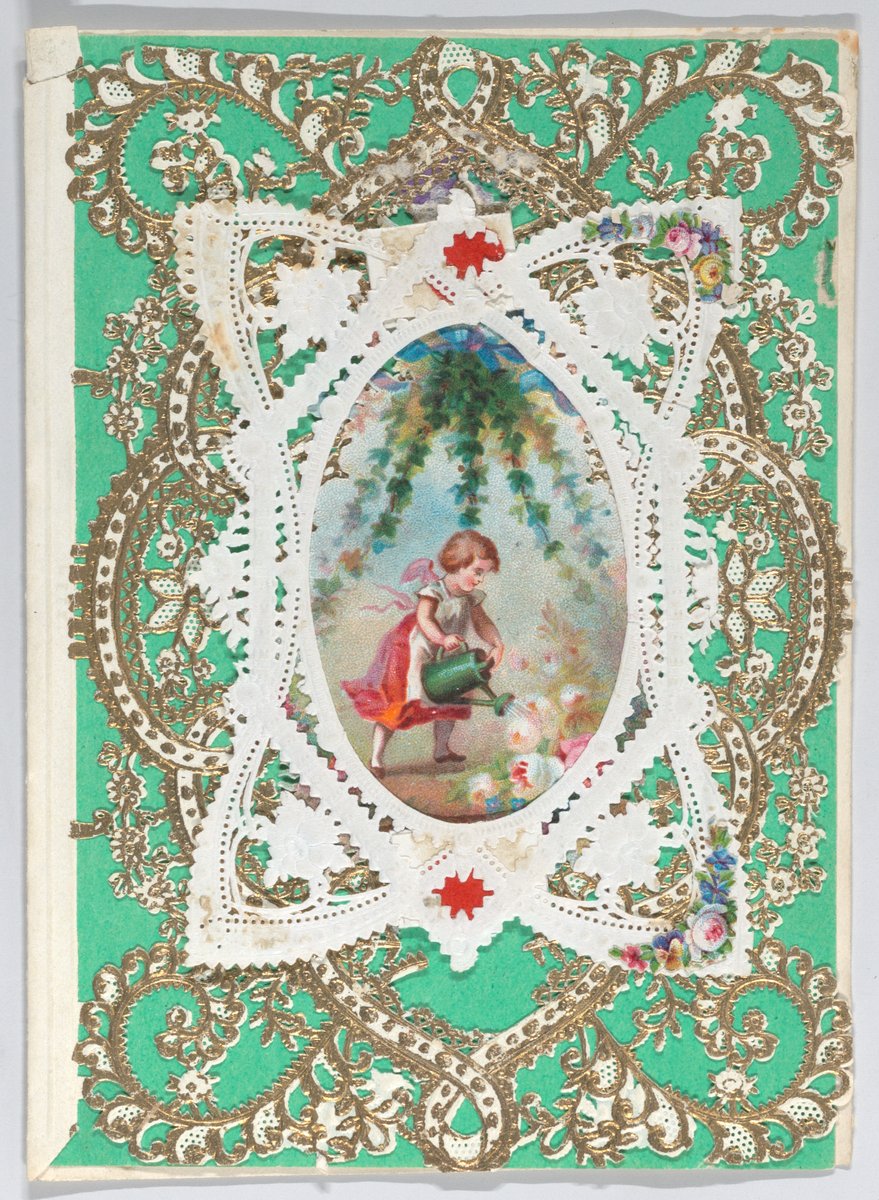

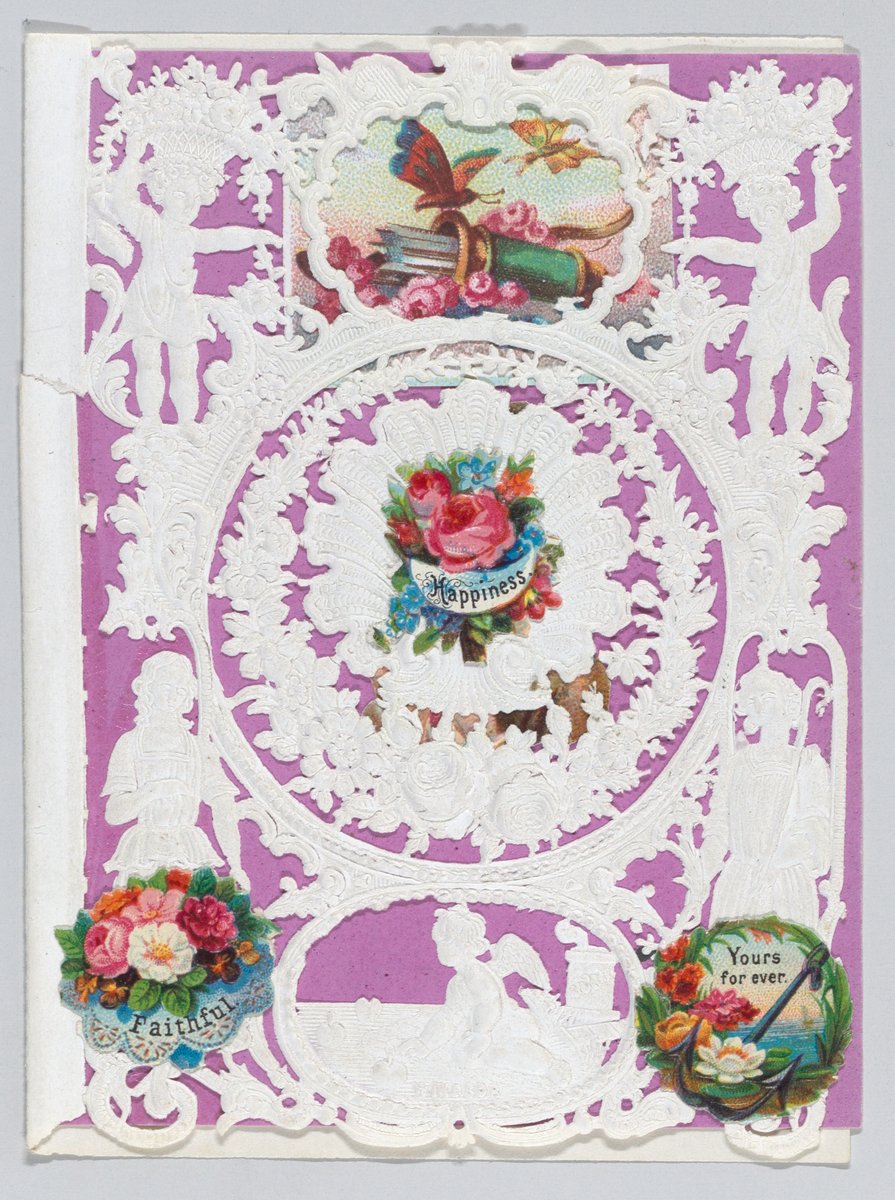

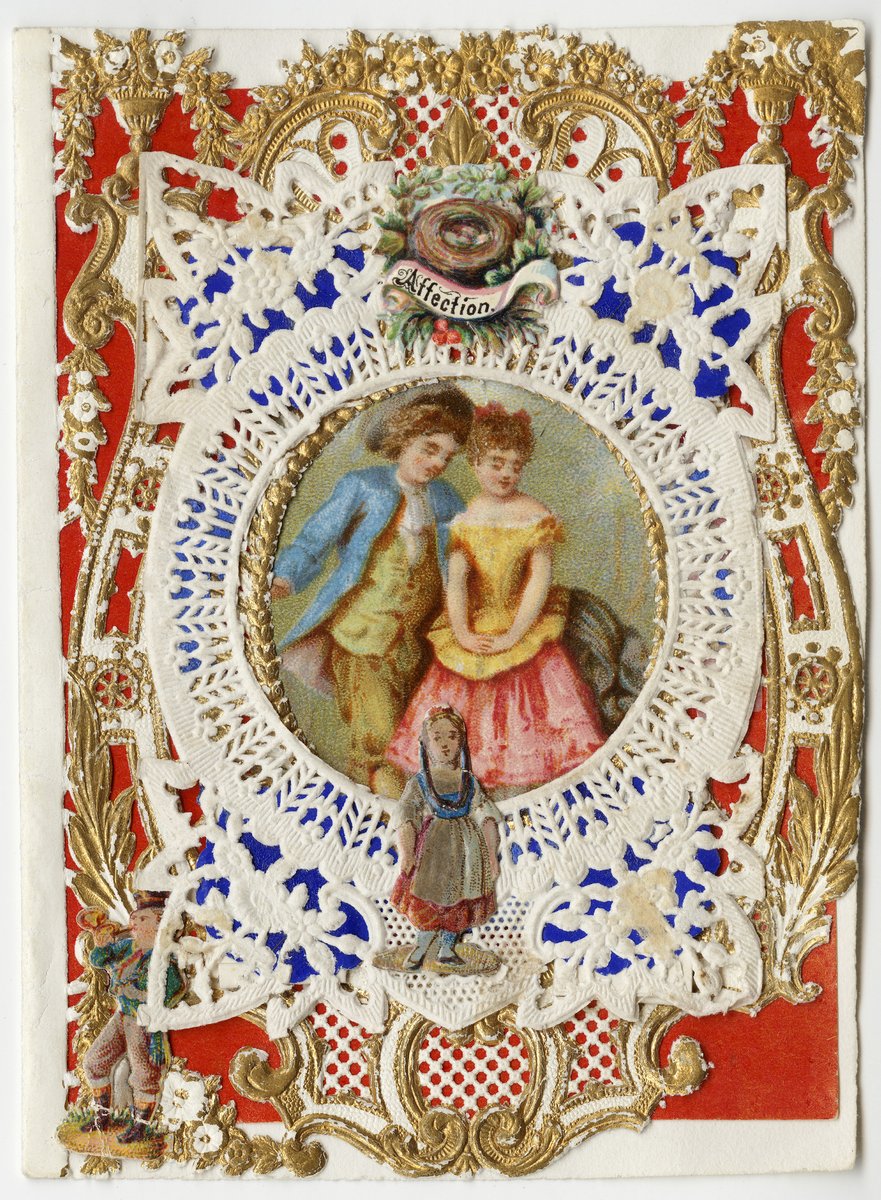

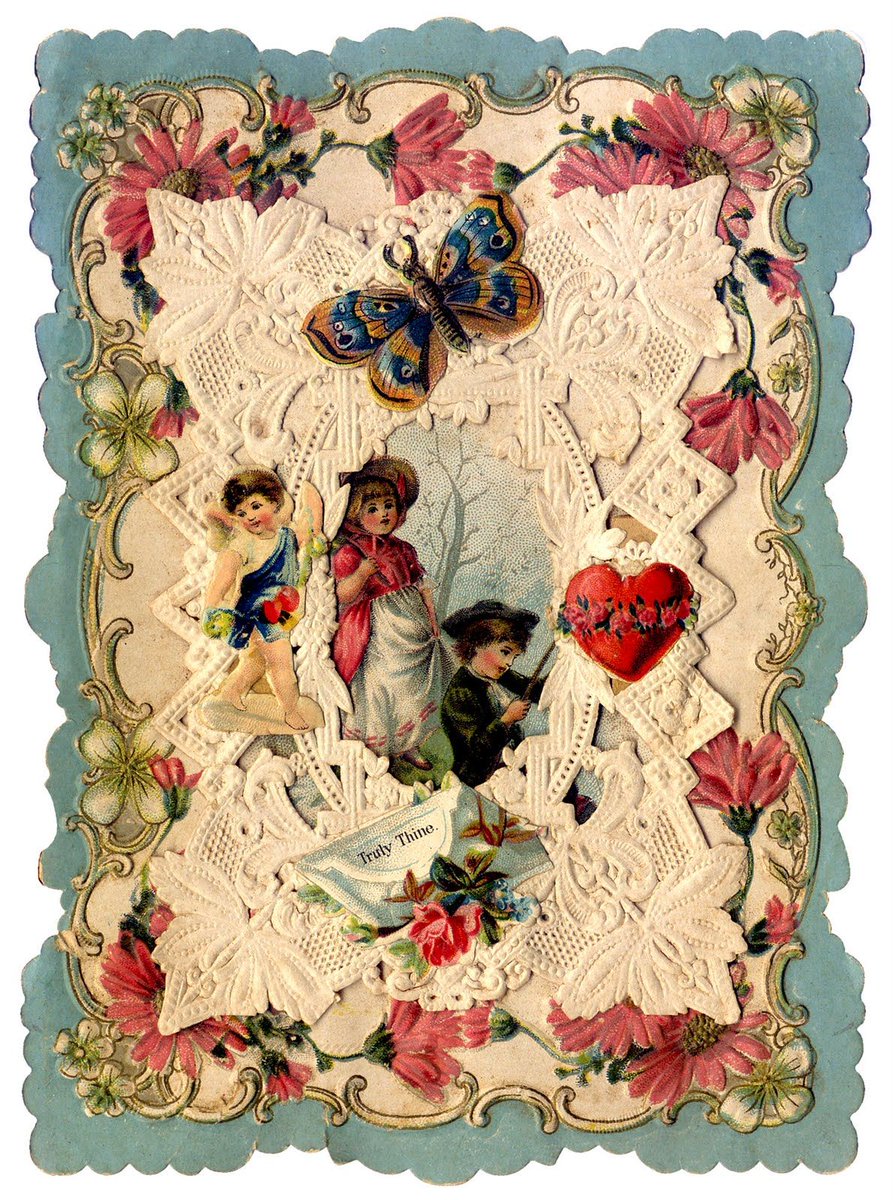

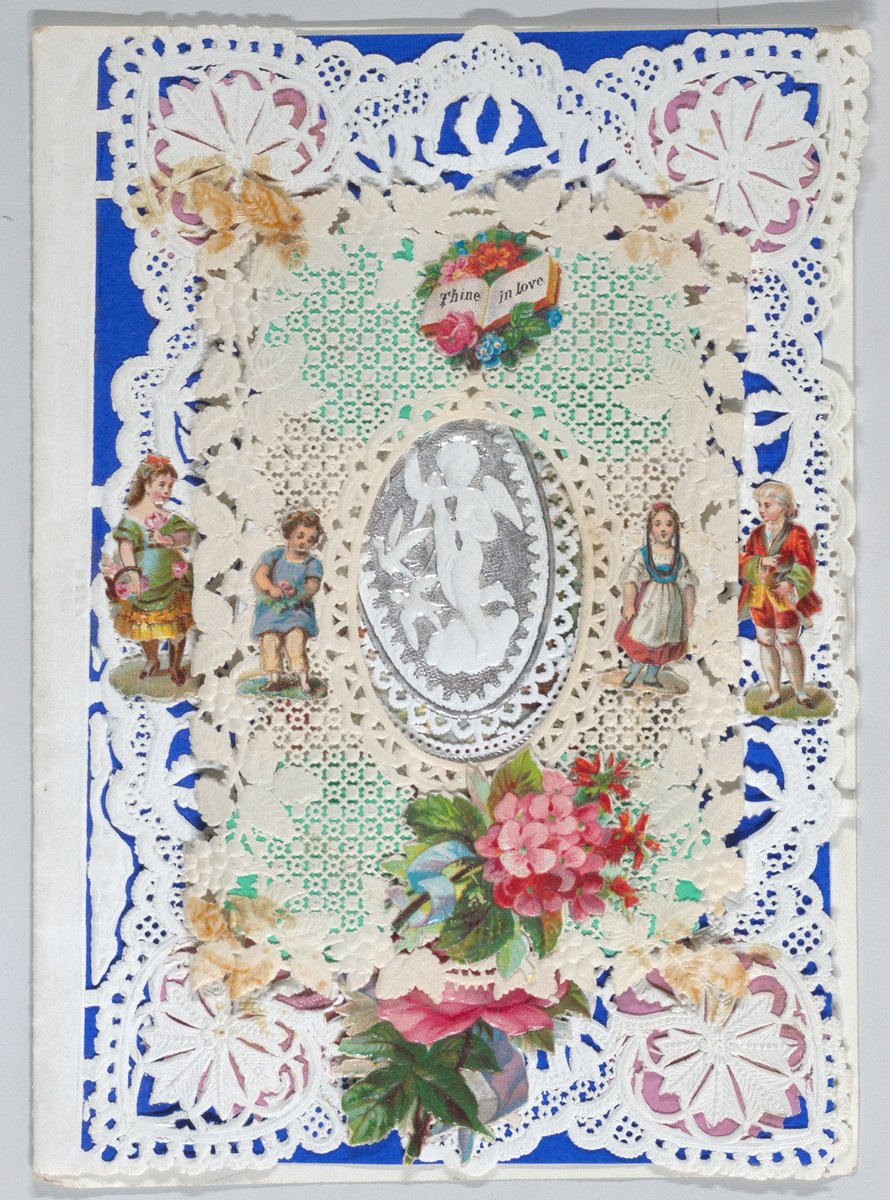

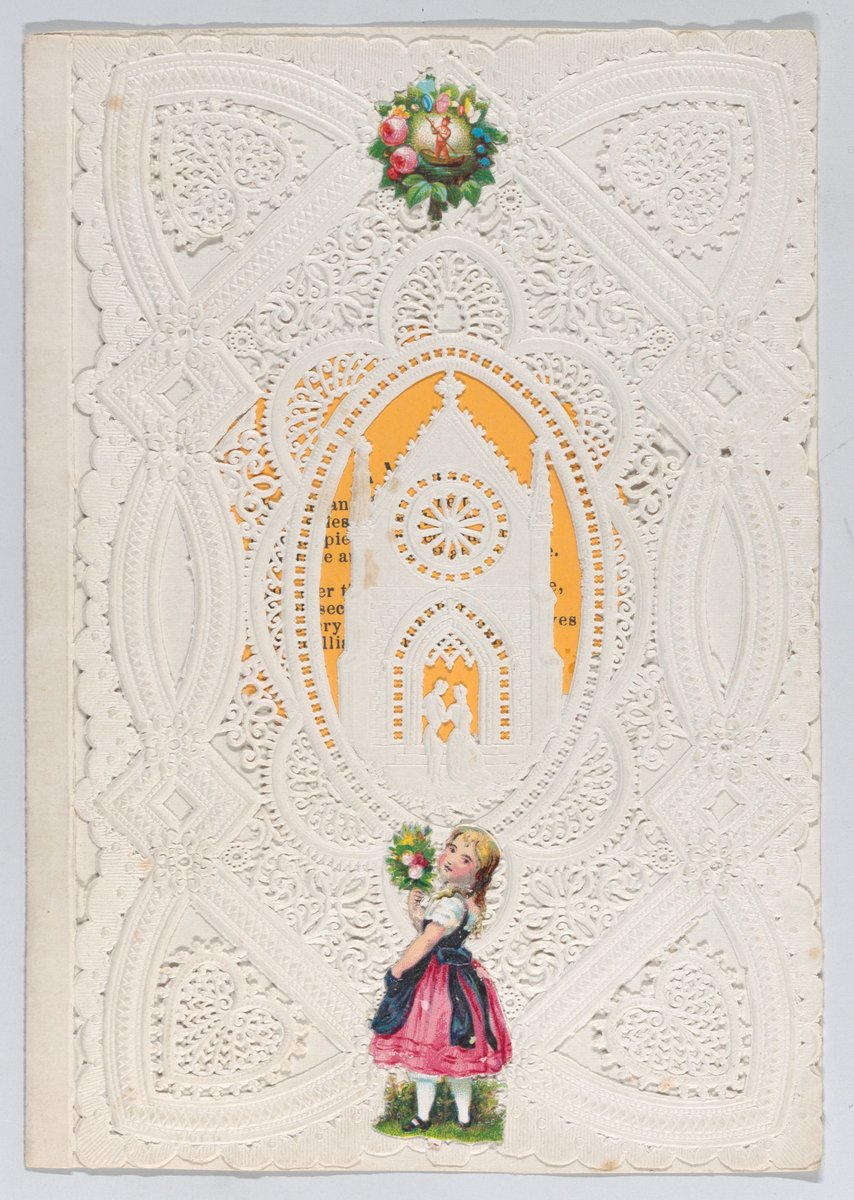

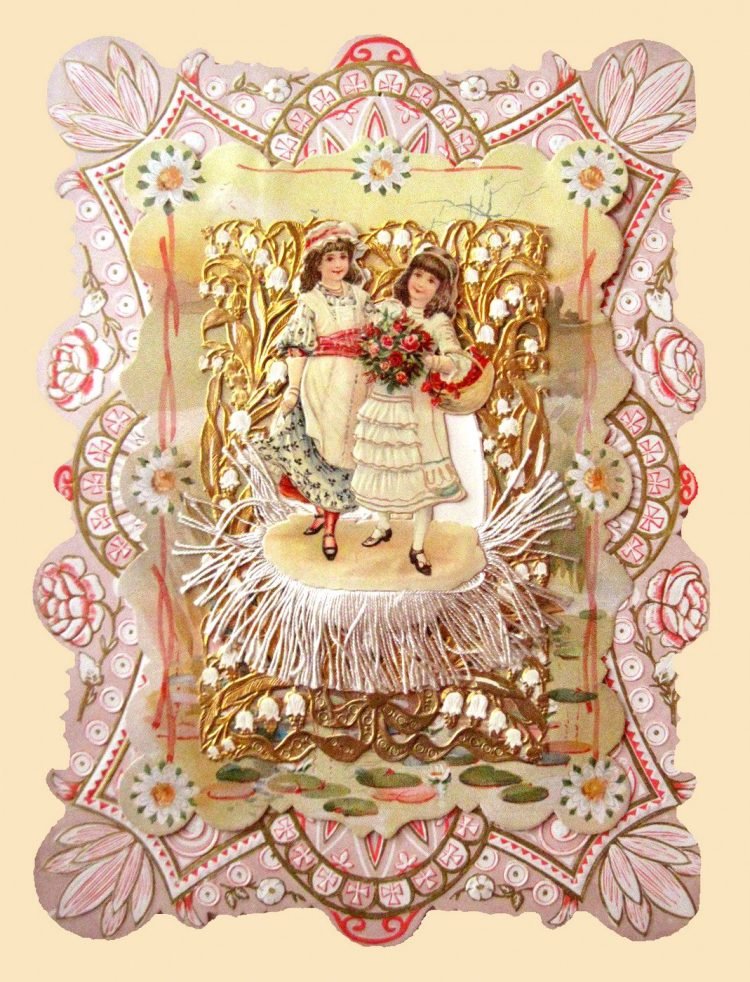

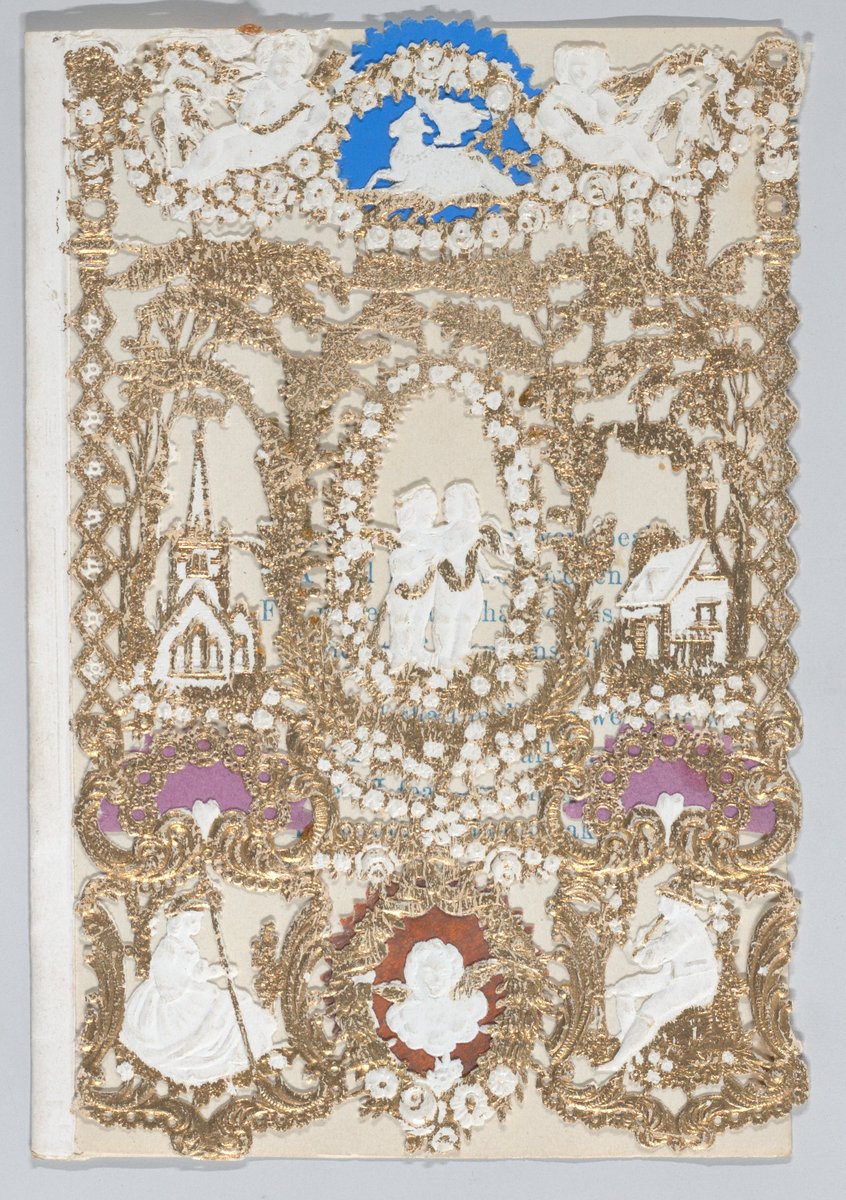

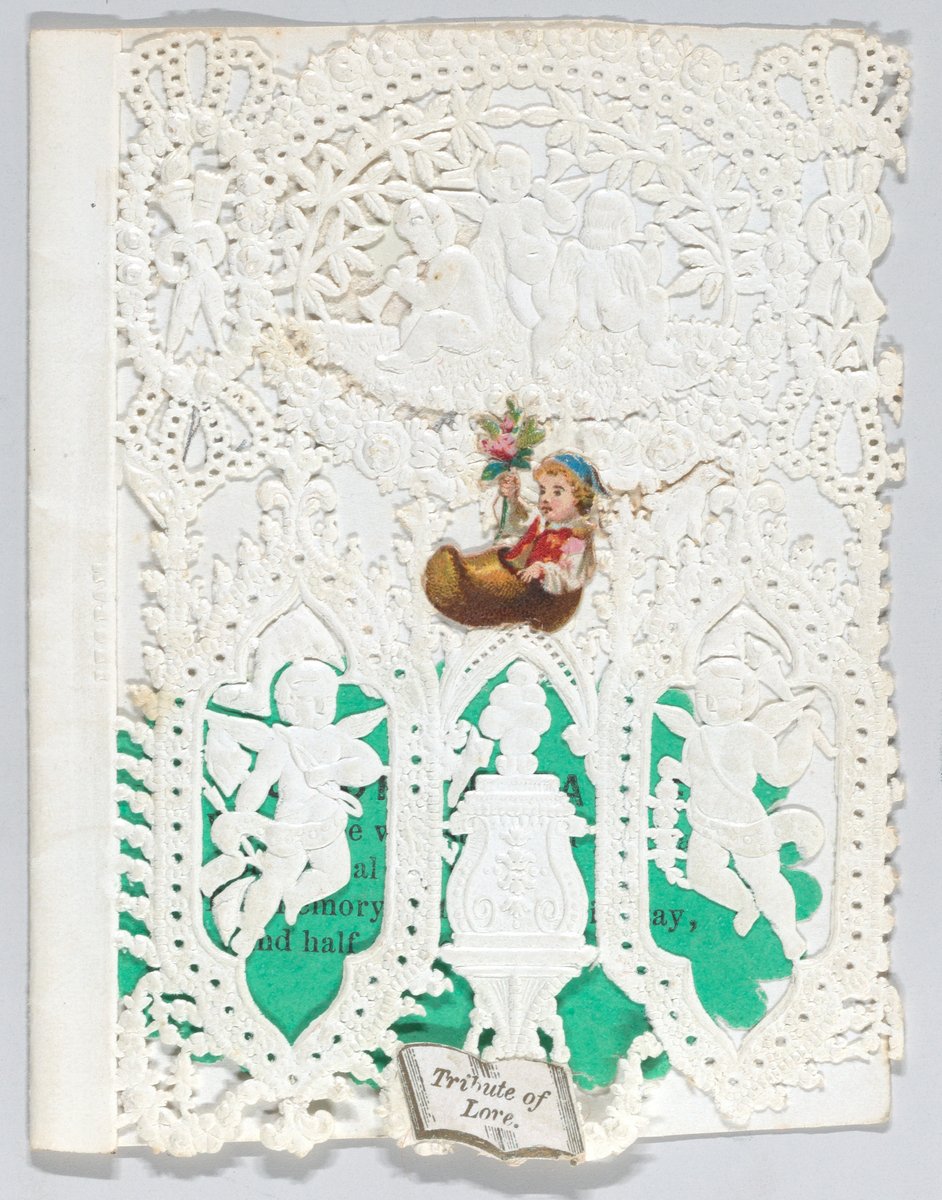

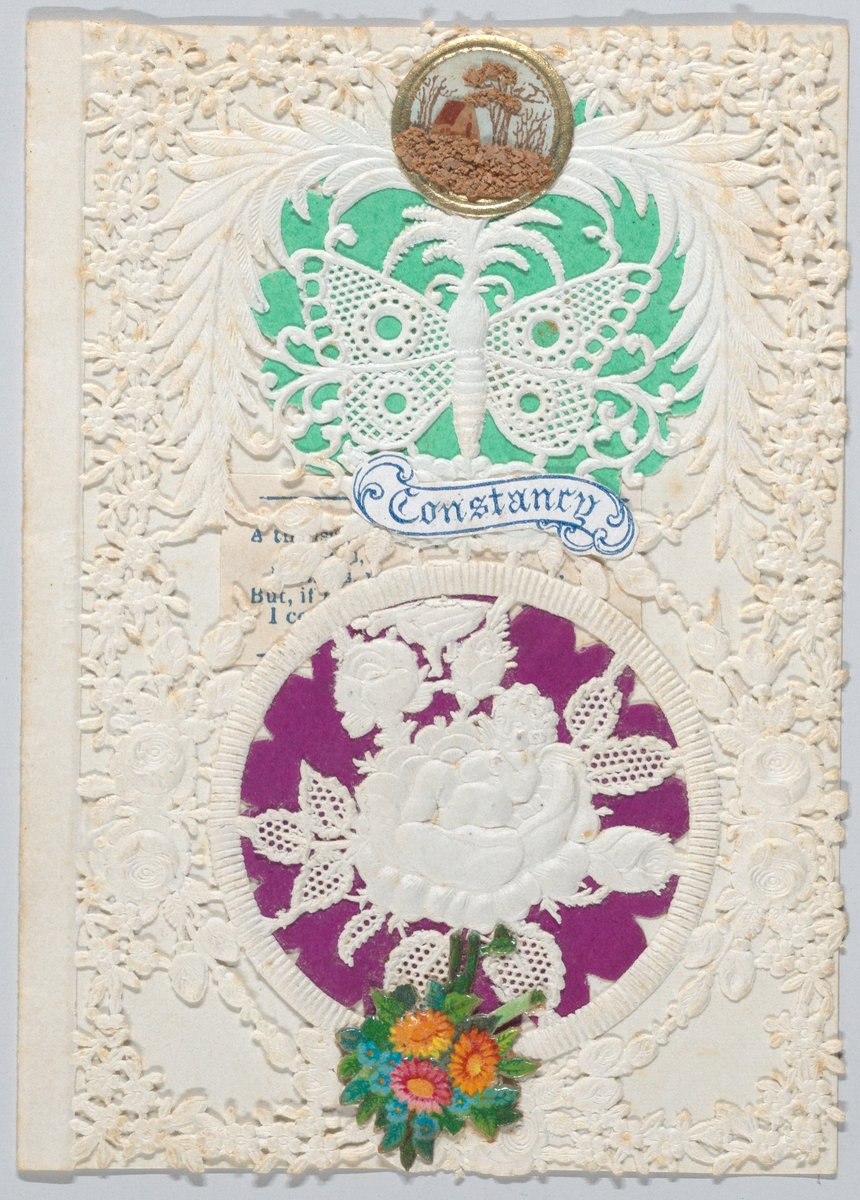

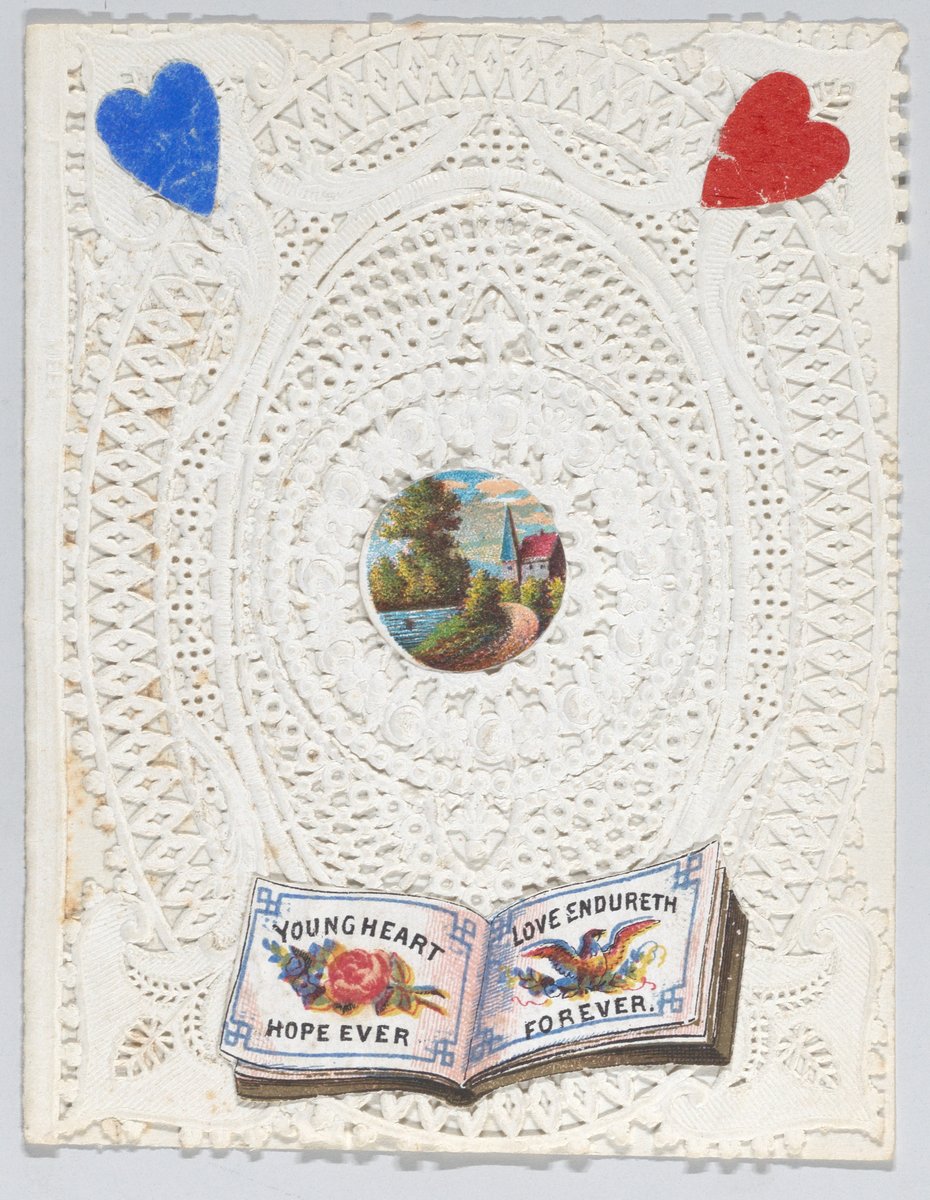

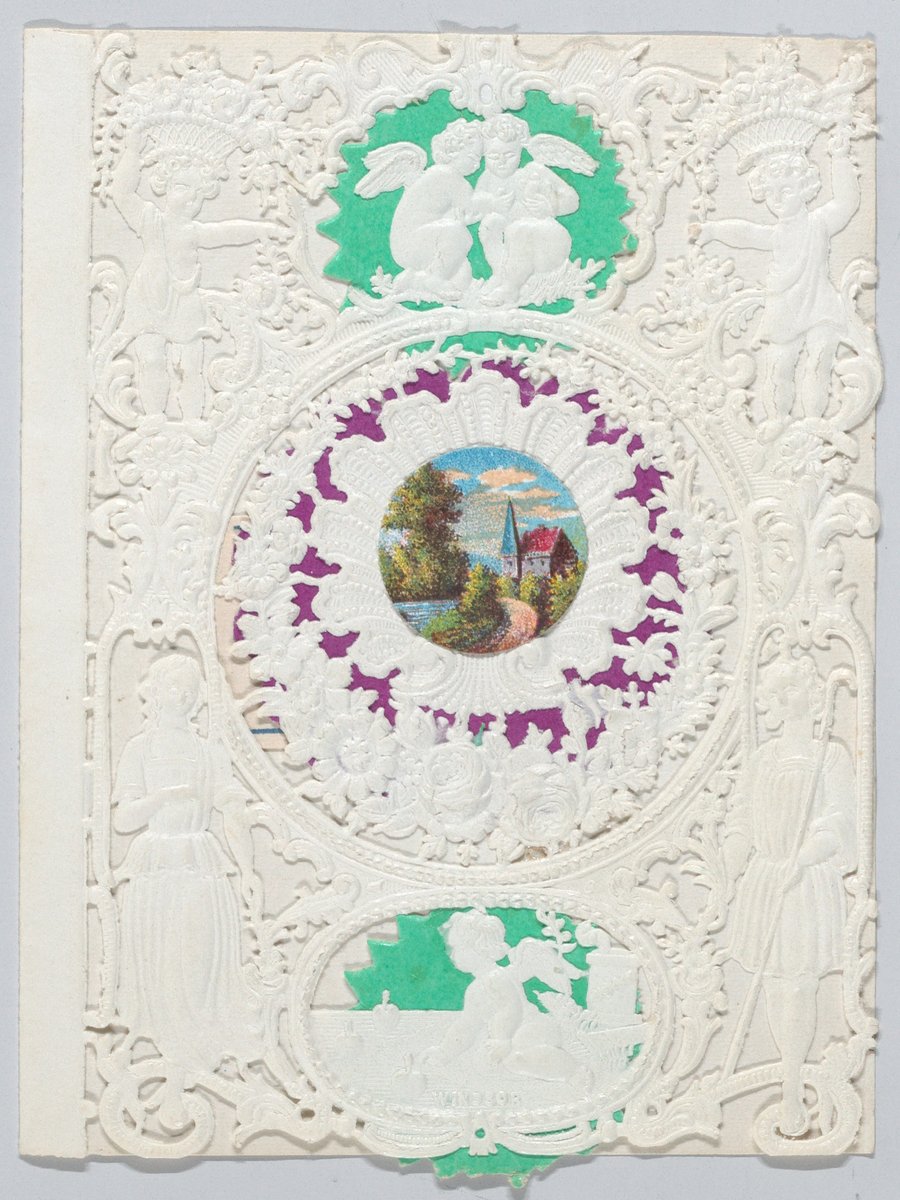

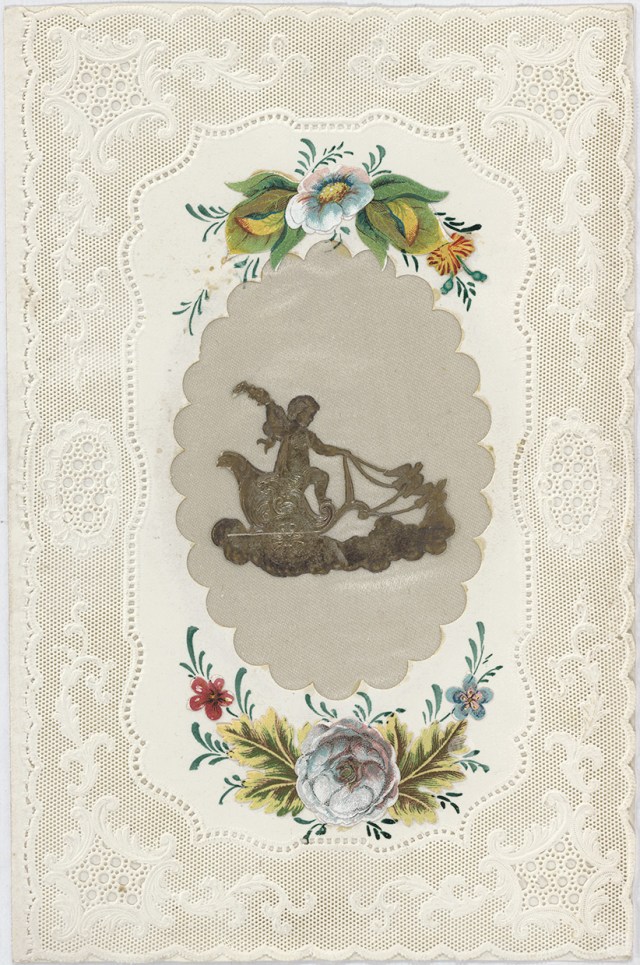

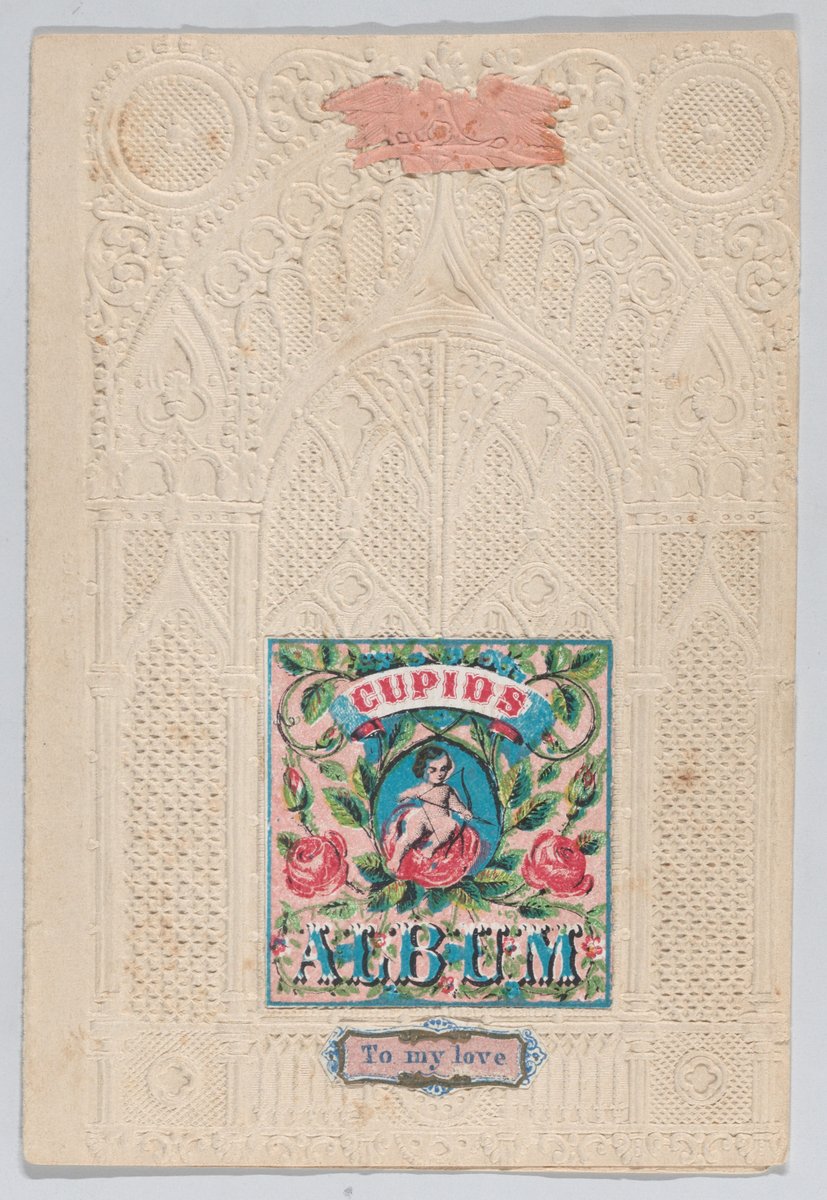

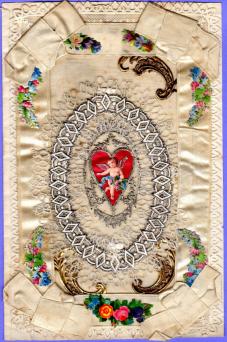

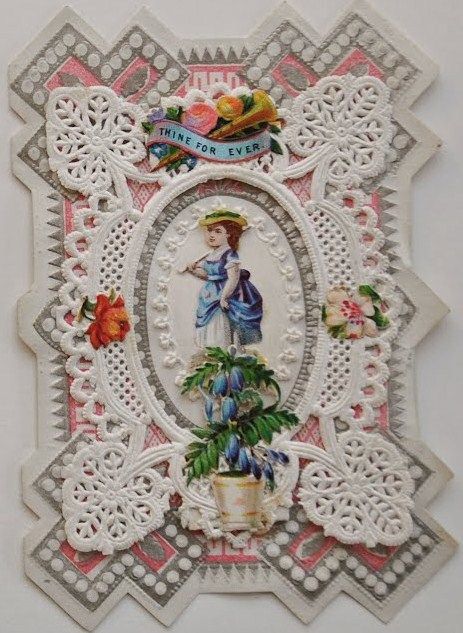

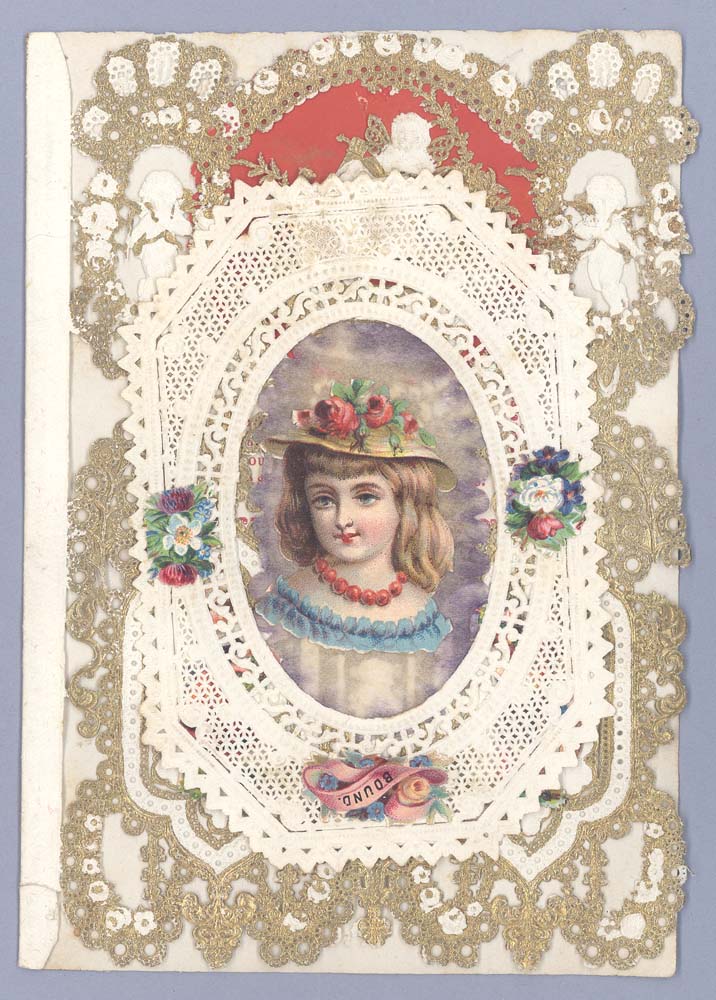

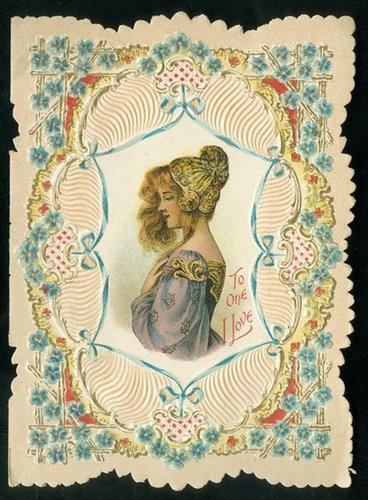

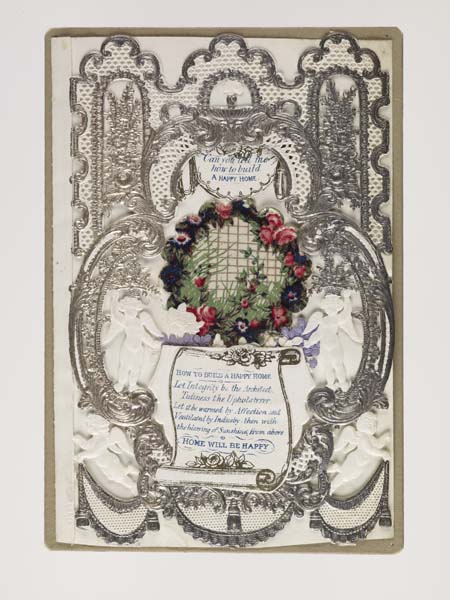

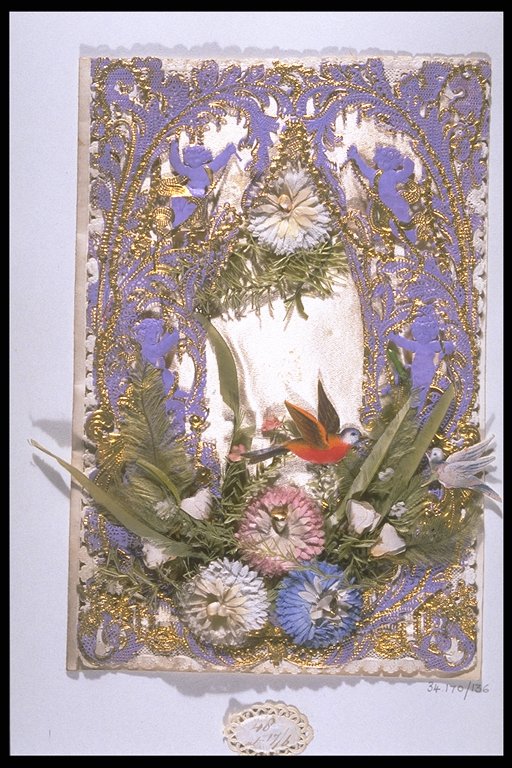

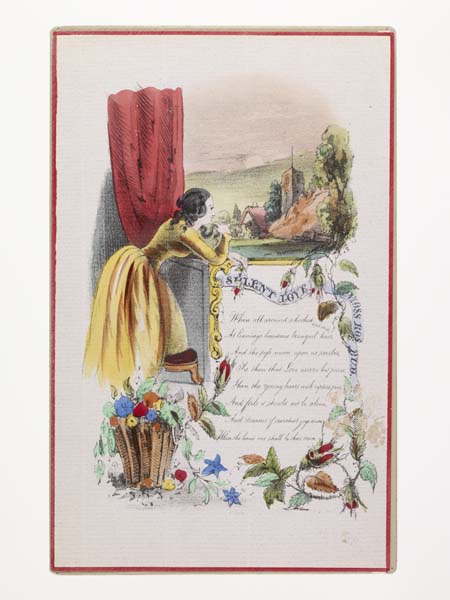

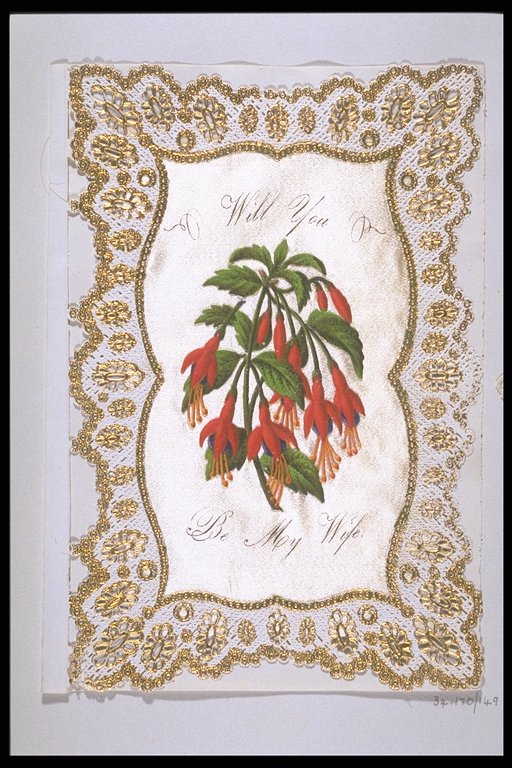

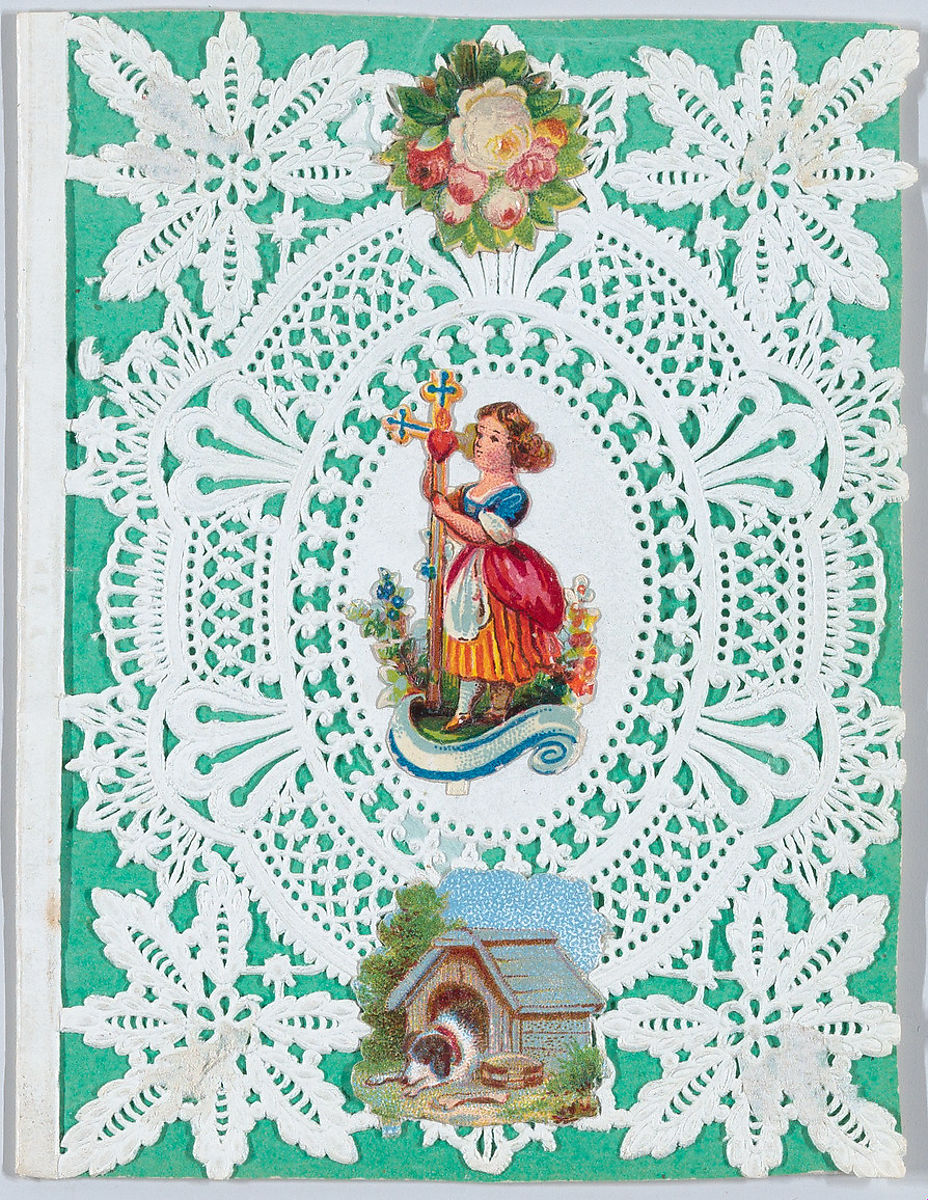

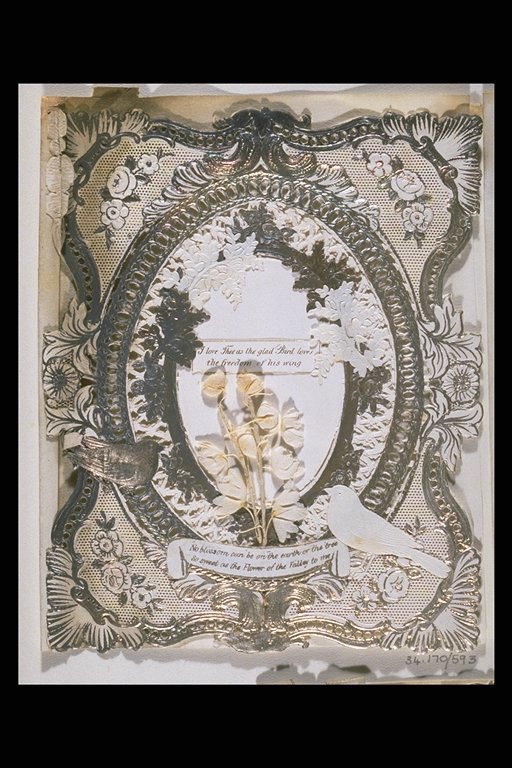

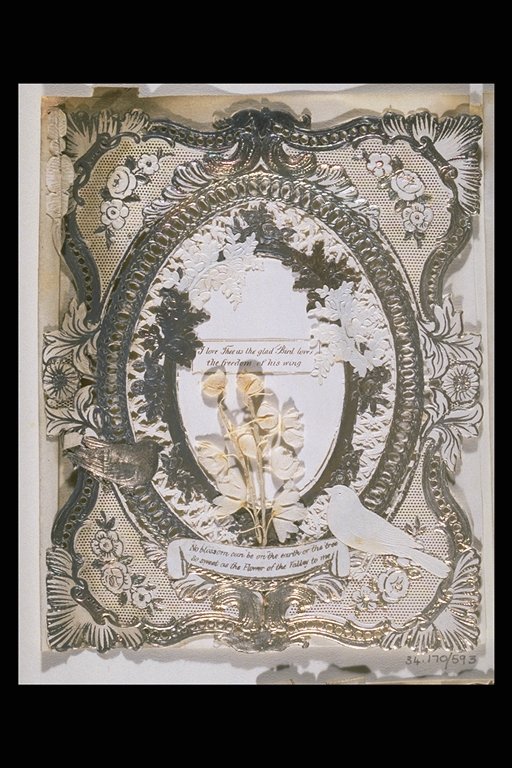

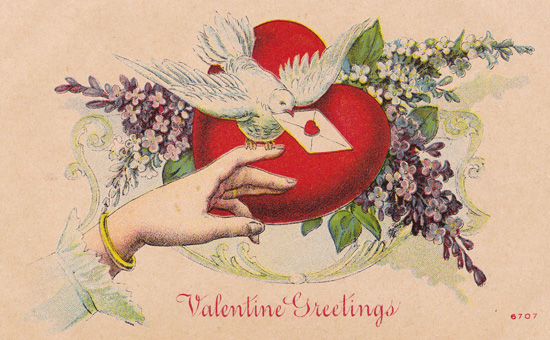

Papers made especially for Valentine greetings began to be marketed in the 1820s, and their use became fashionable in both Britain and the United States.

In the 1840s, when postal rates in Britain became standardized, commercially produced Valentine cards began to grow in popularity. The cards were flat paper sheets, often printed with colored illustrations and embossed borders.

Valentine’s Day became so popular that postal carriers received special meal allowances to keep themselves running during the frenzy leading up February 14th.

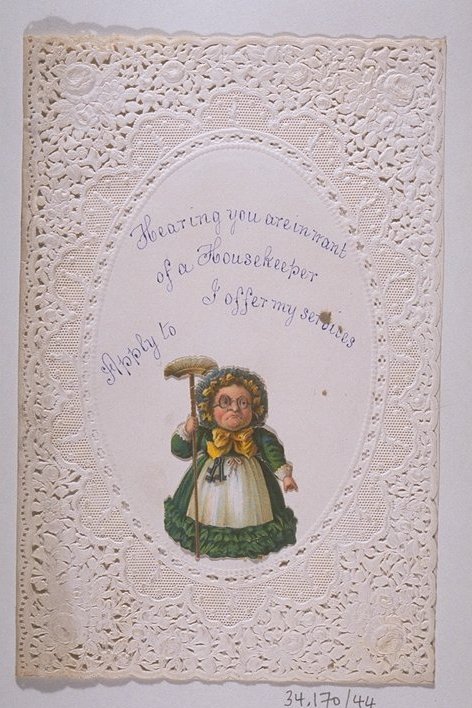

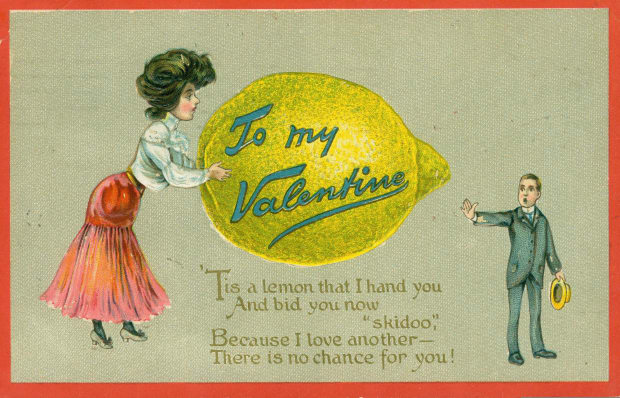

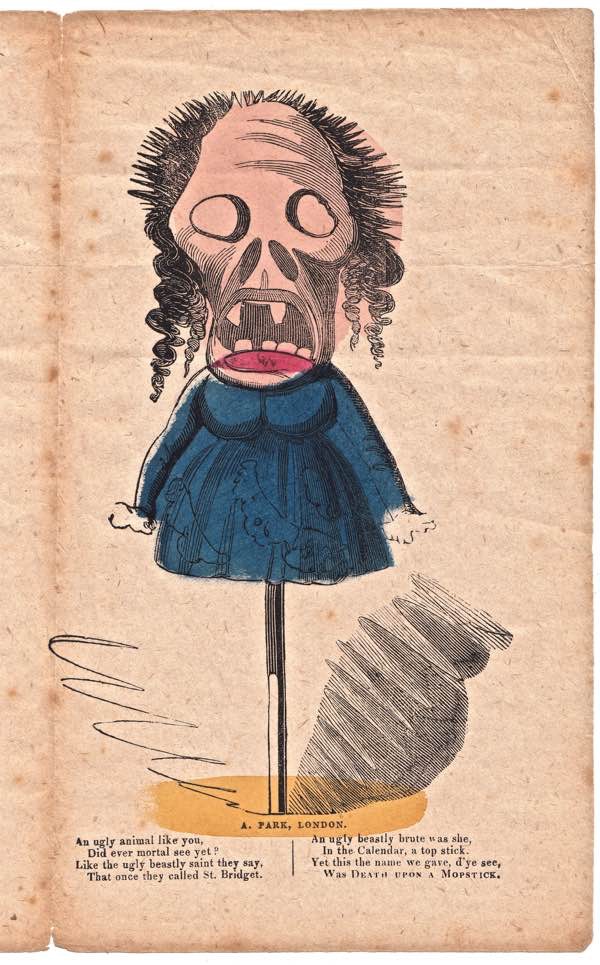

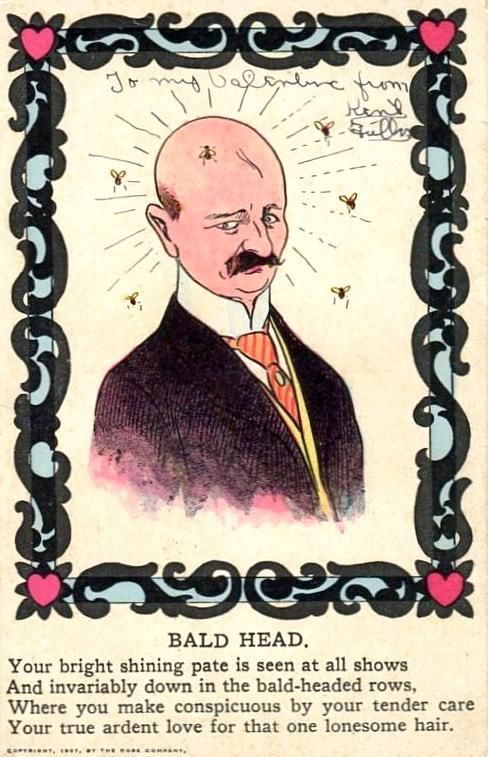

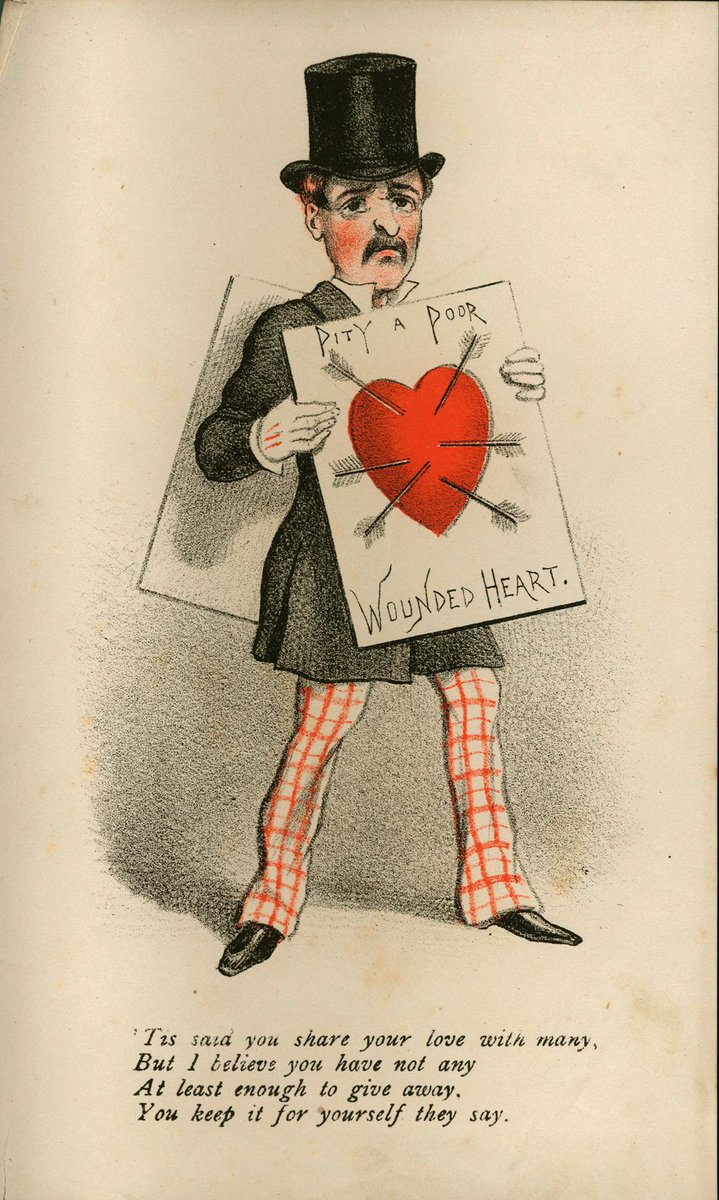

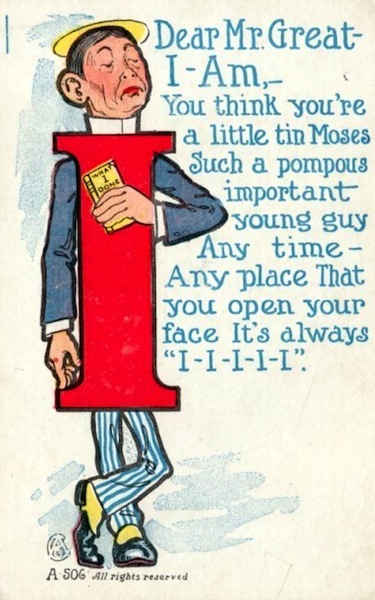

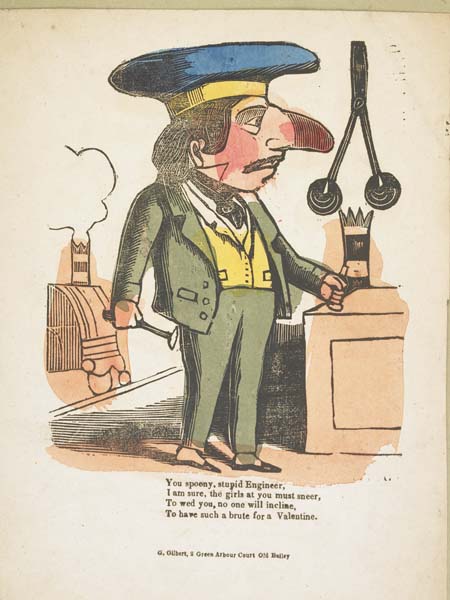

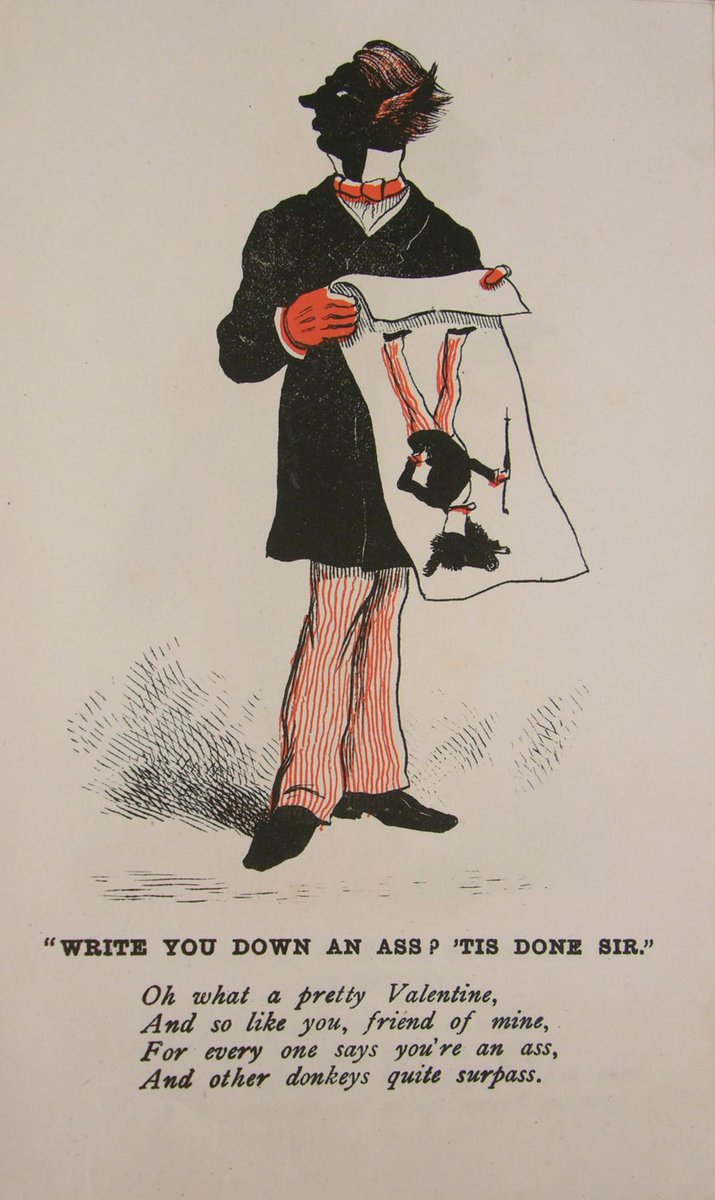

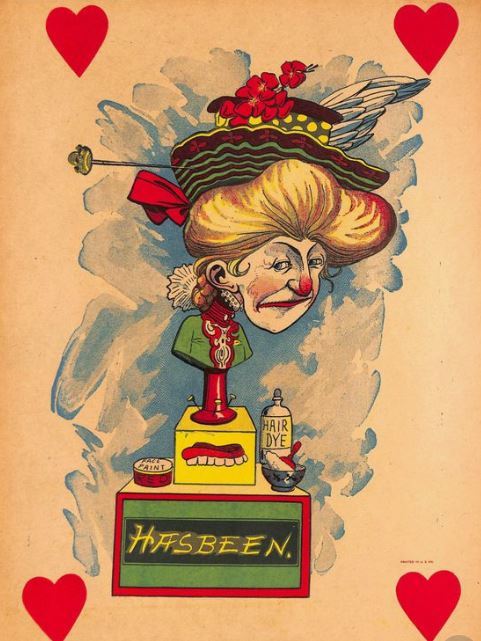

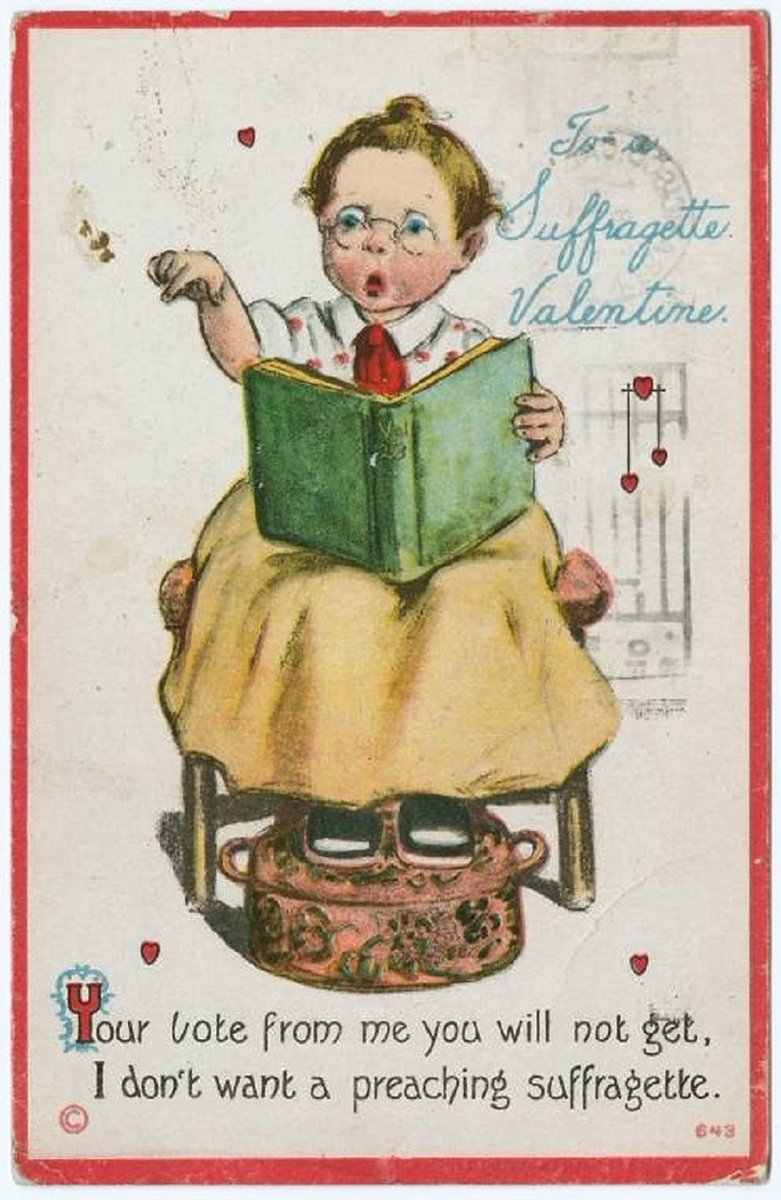

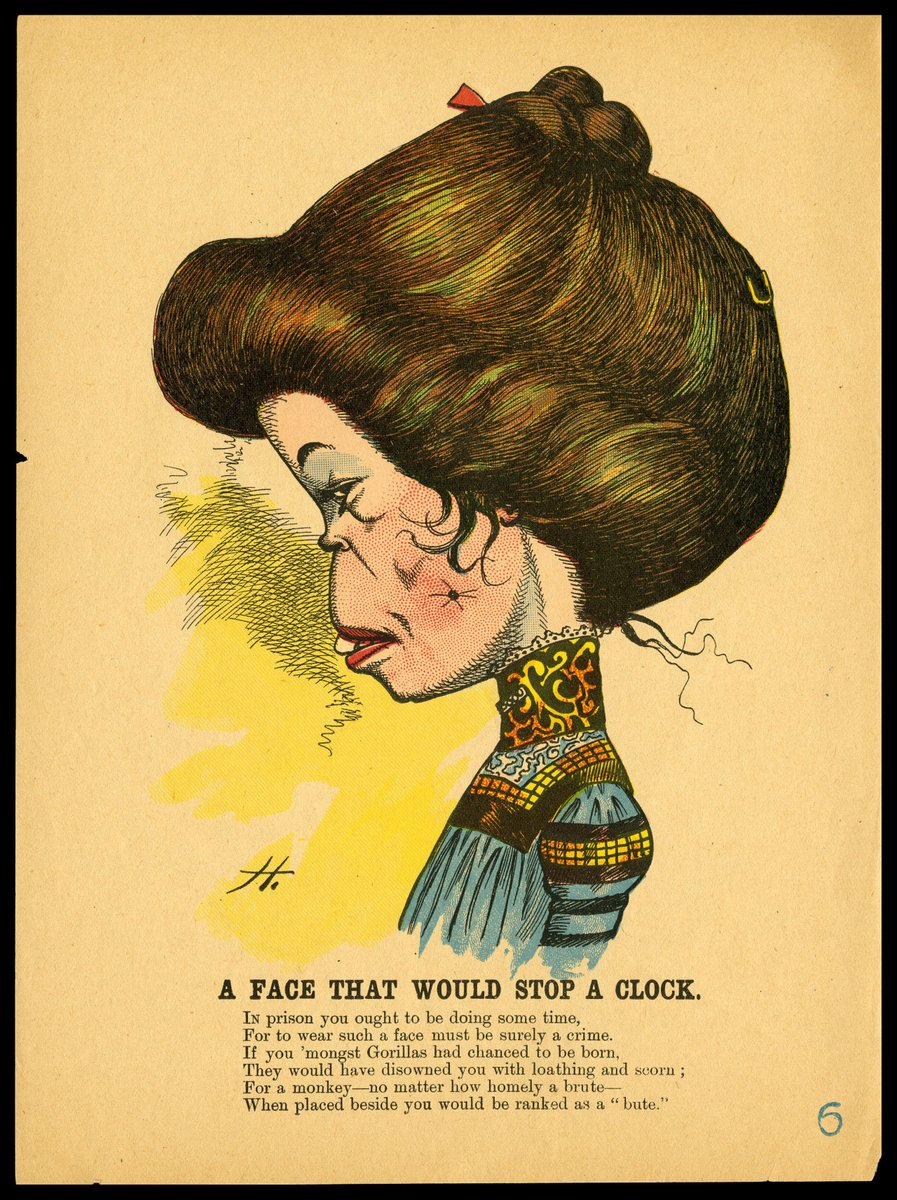

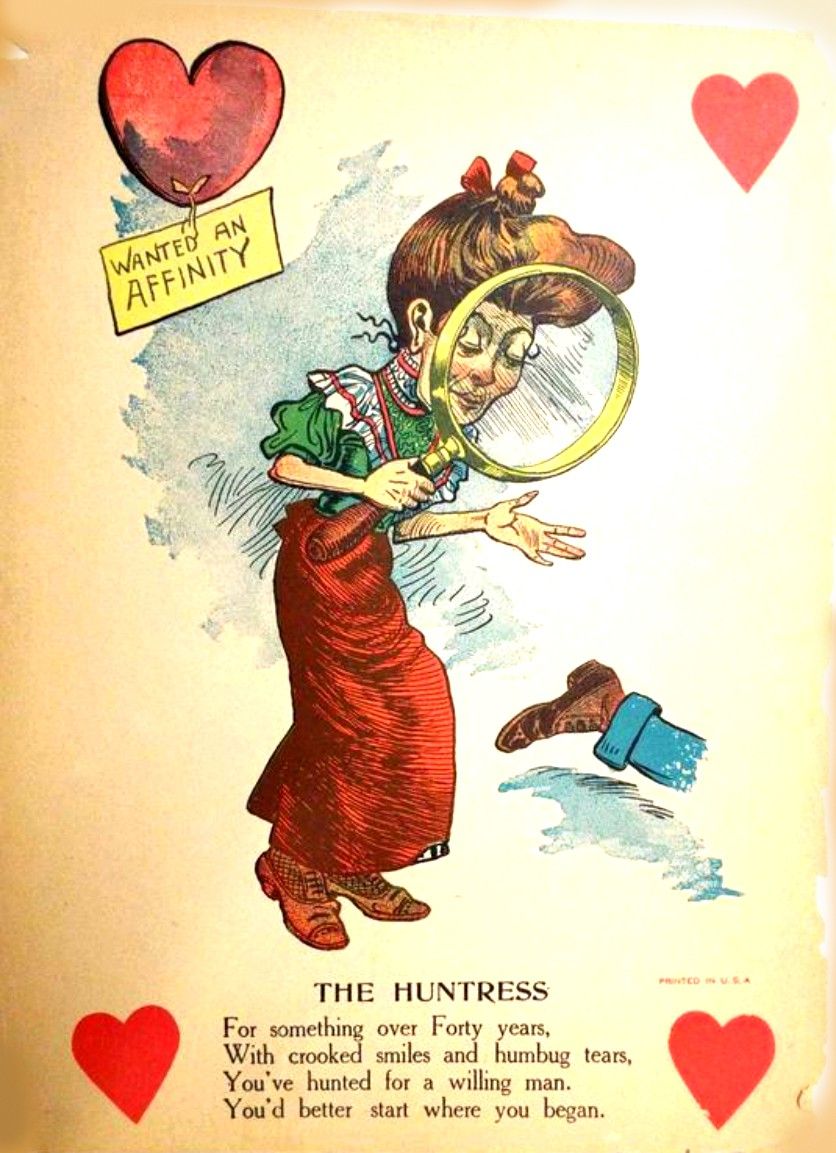

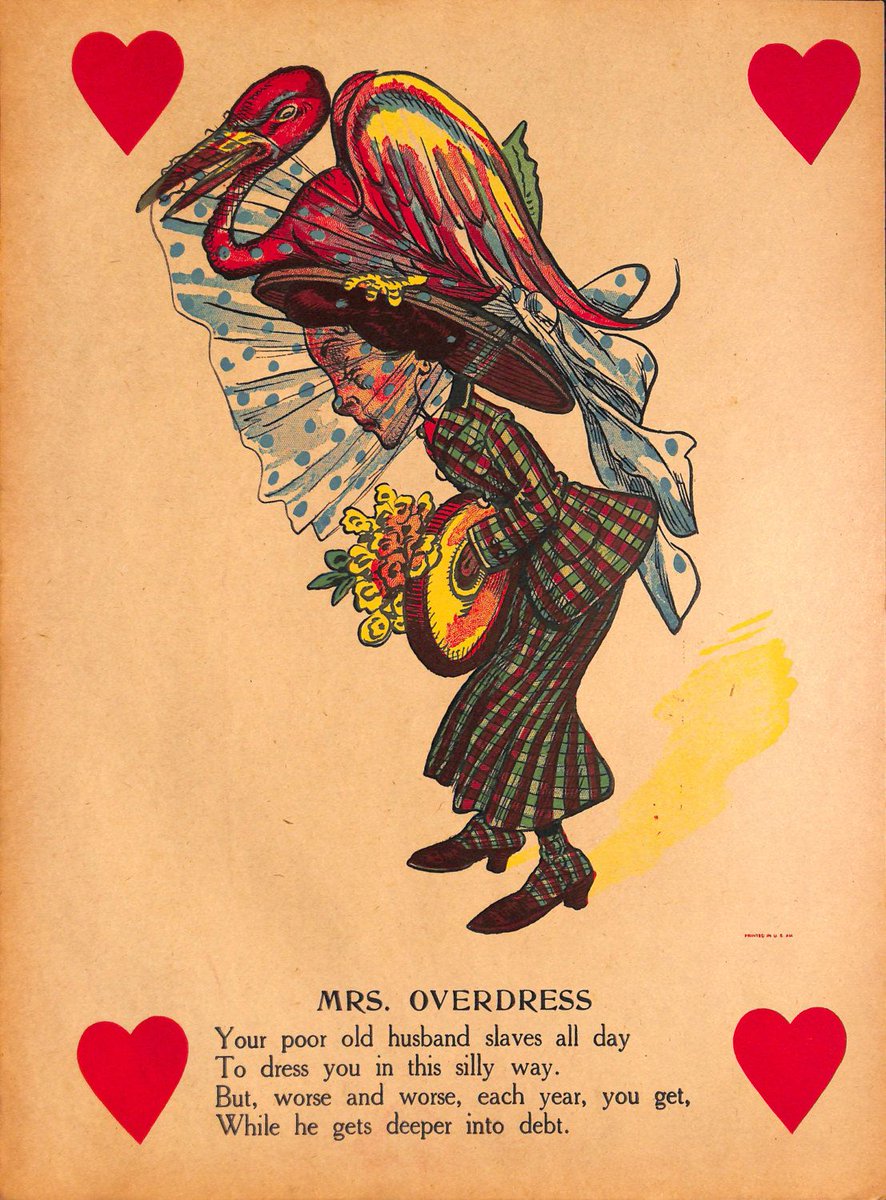

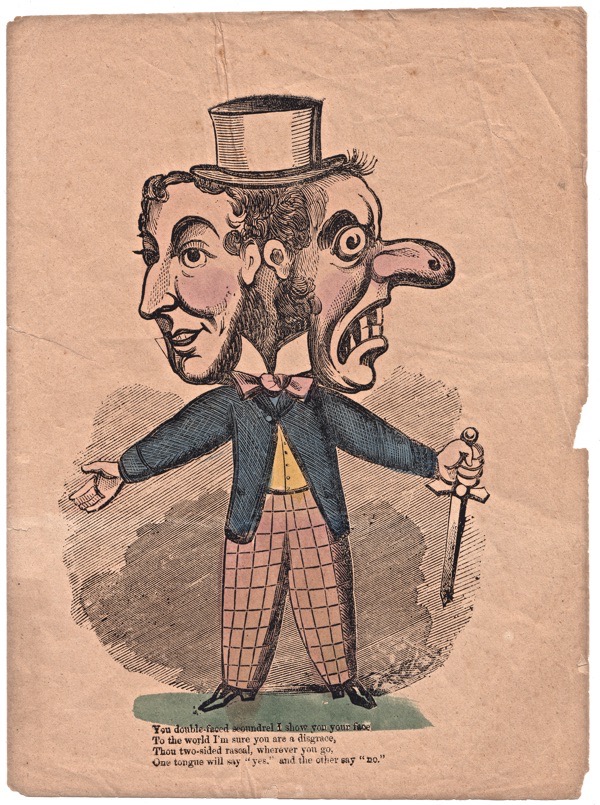

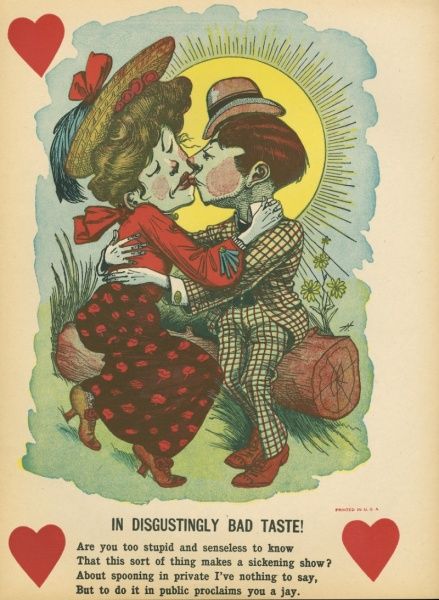

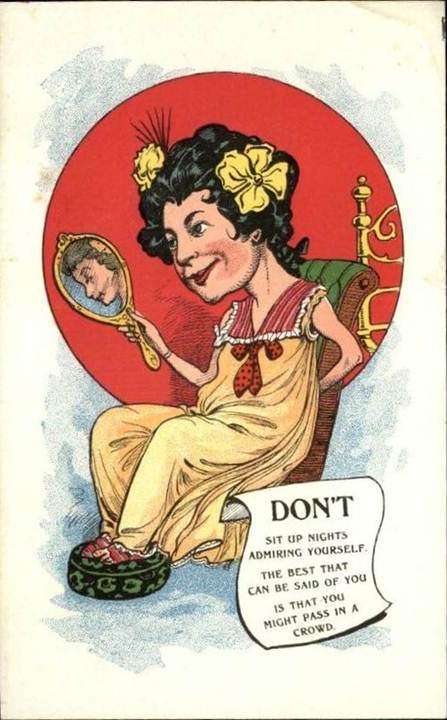

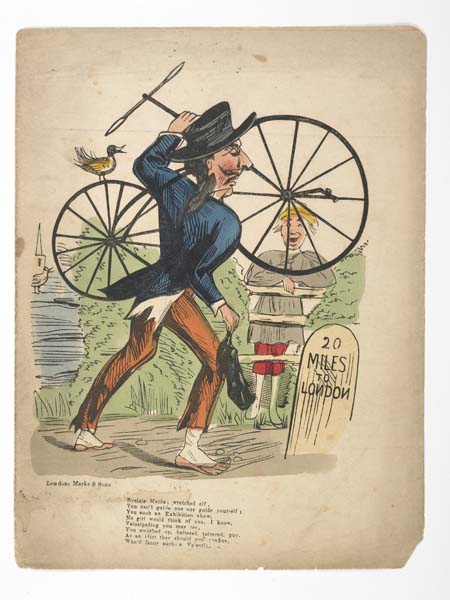

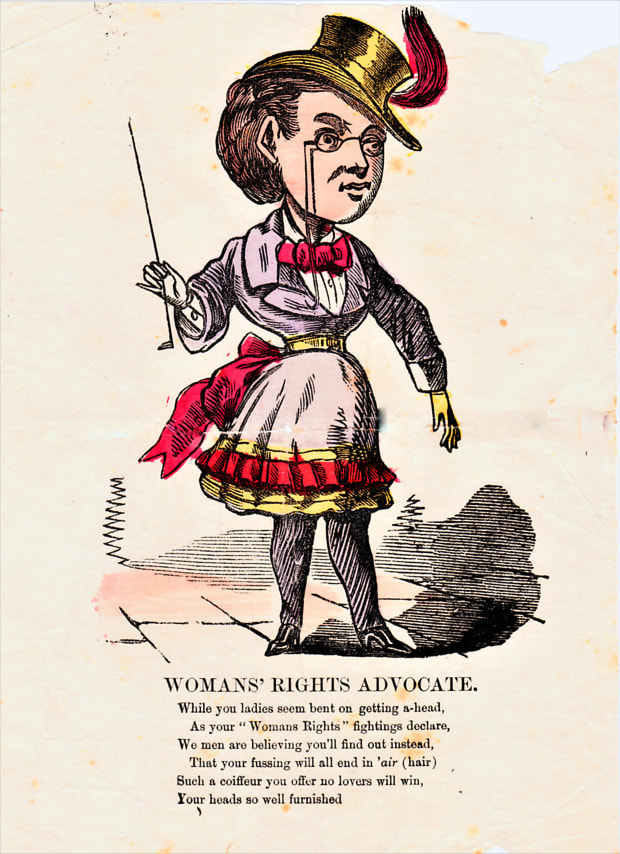

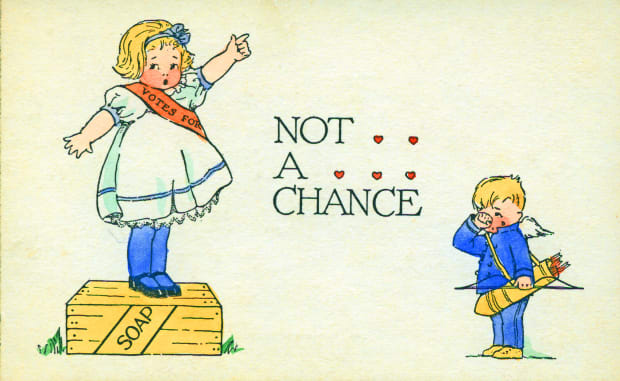

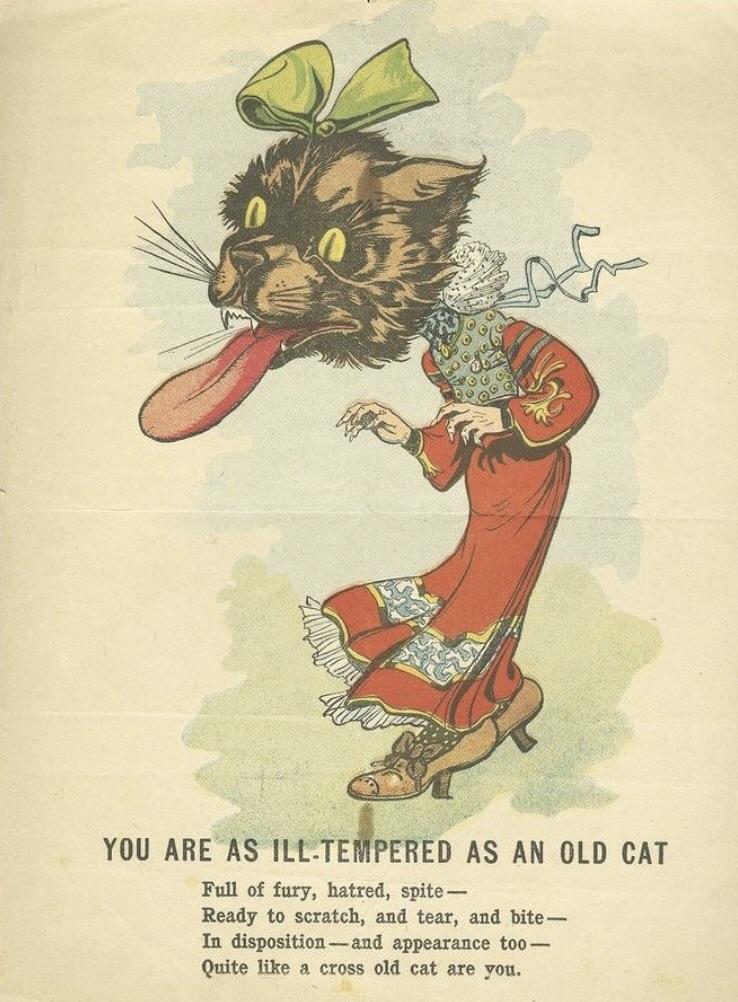

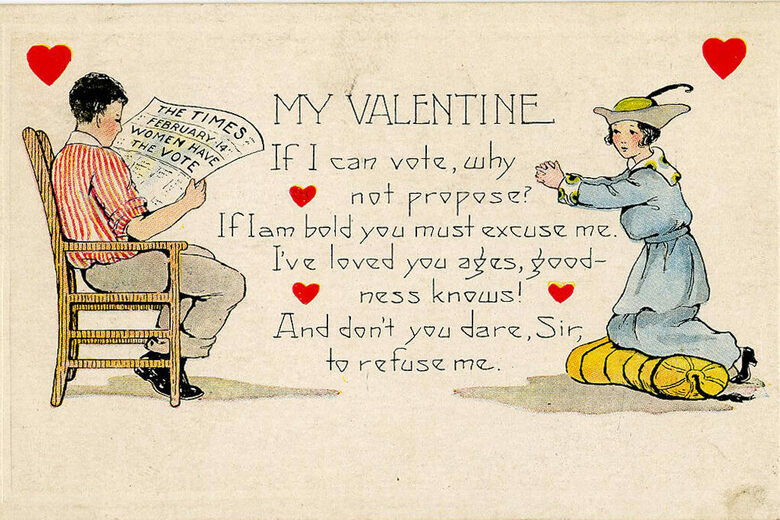

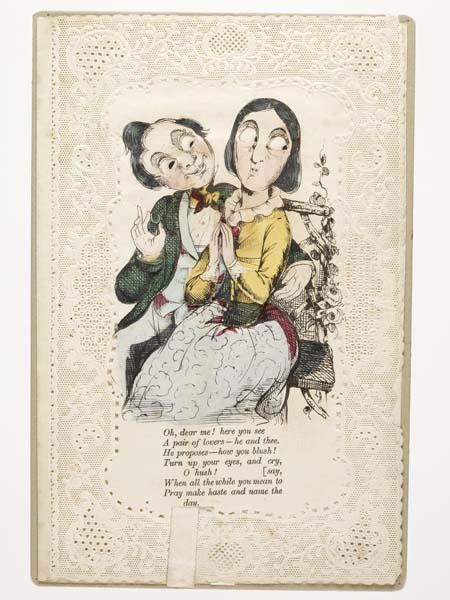

Of the millions of cards sent, some estimate that nearly half were of the vinegar variety.What are now known as 'vinegar' valentines by 21st century dealers and collectors seem to have their origin in the 1830s and 1840s.

This coincides with the growth of valentines as a popular form of communication, assisted by the development of a range of wider phenomena, such as cheap printing and fancy paper production,

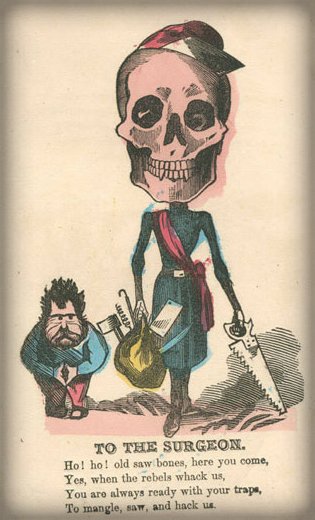

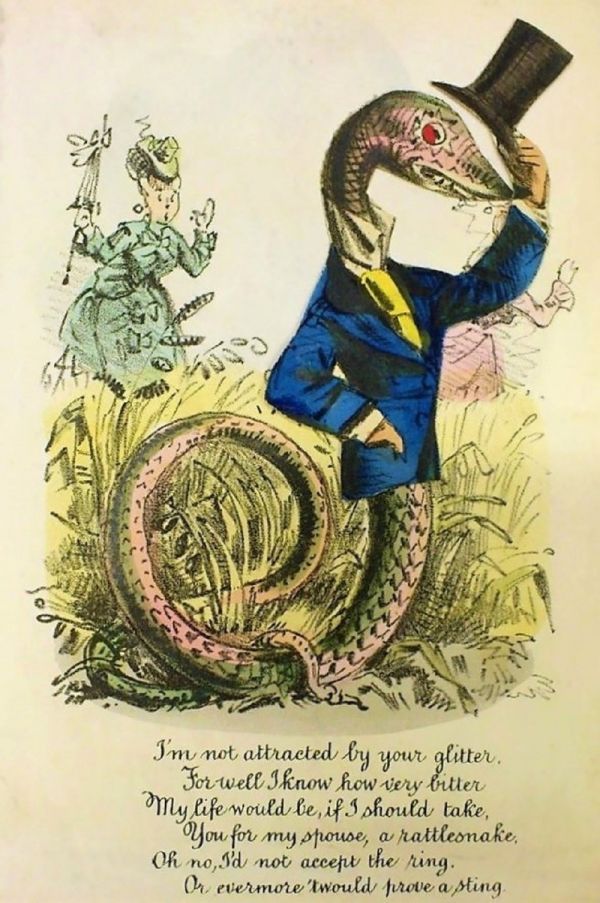

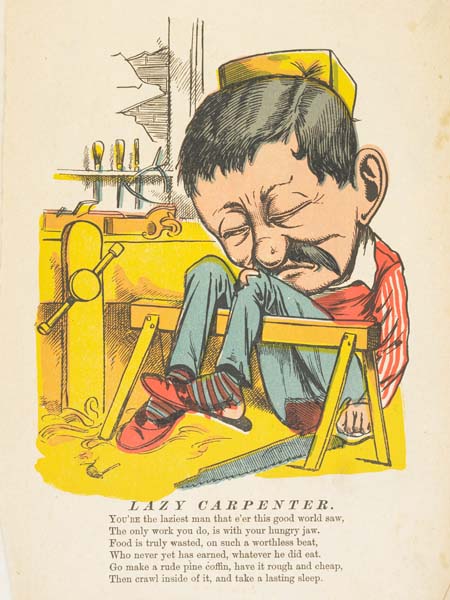

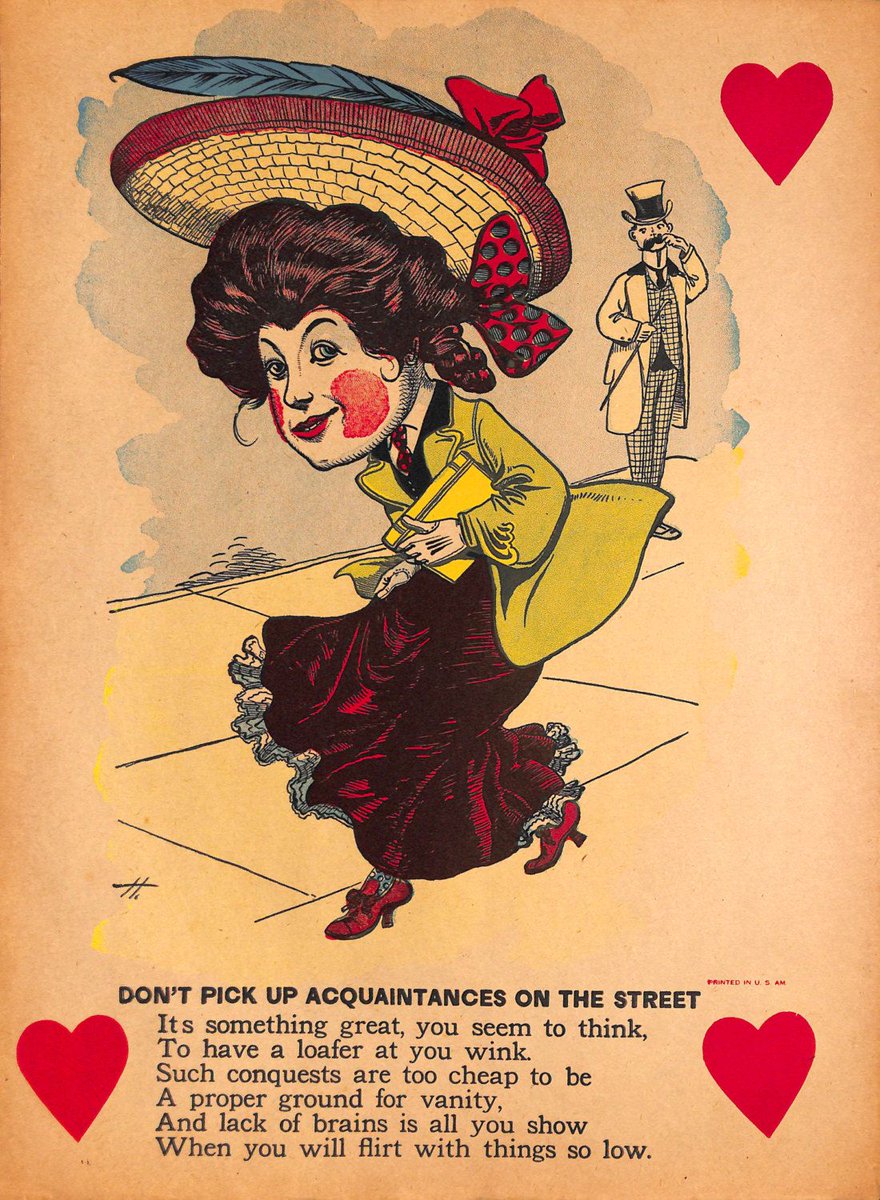

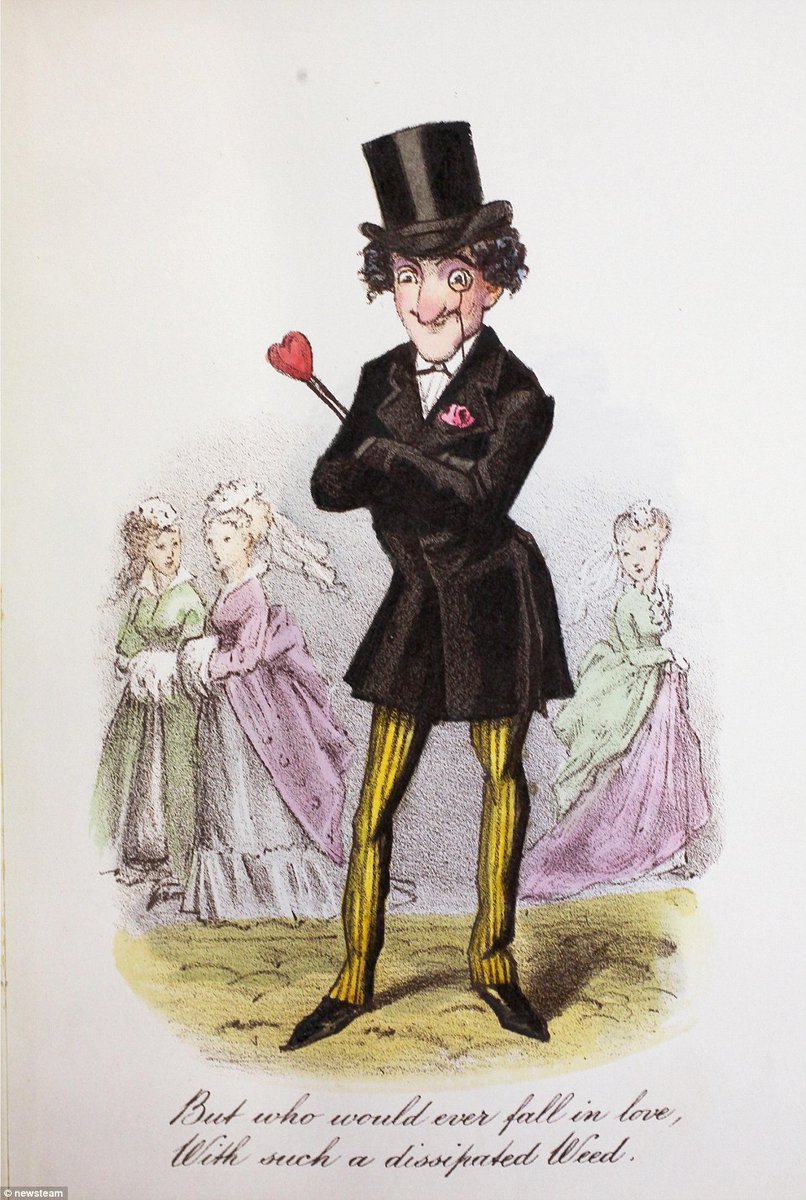

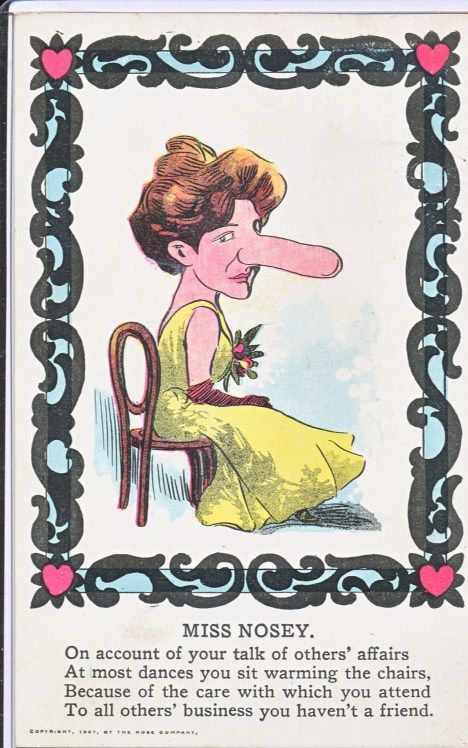

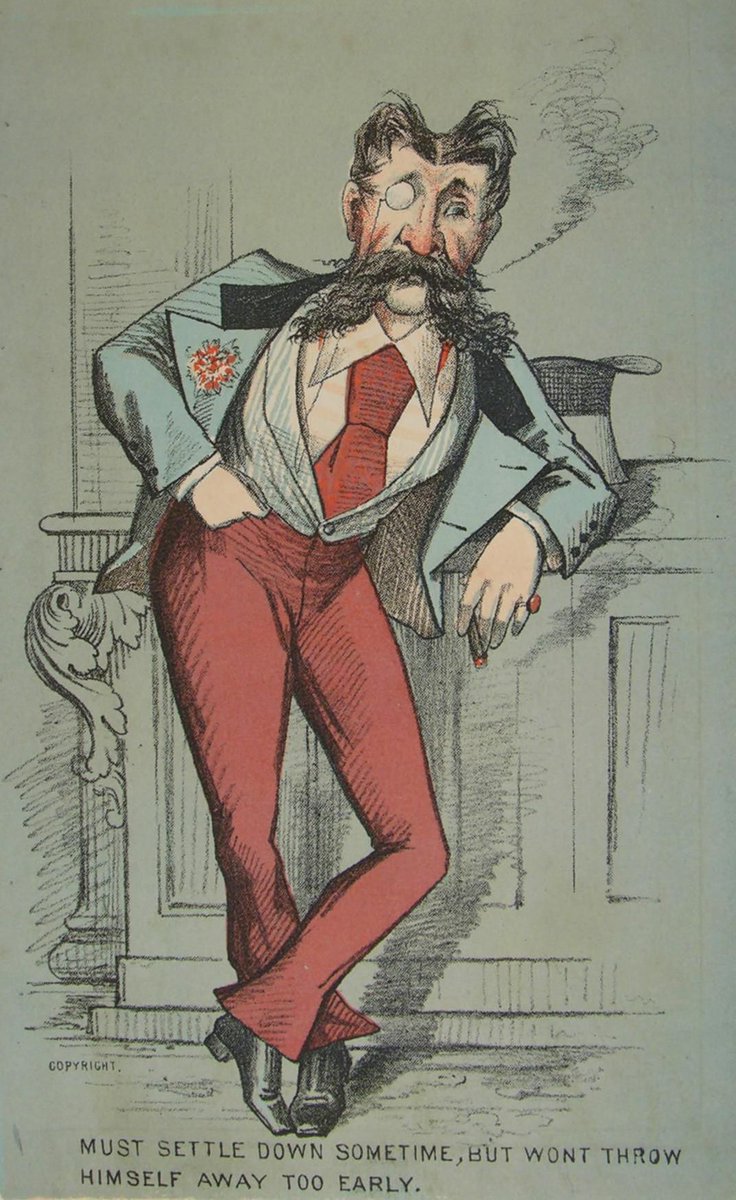

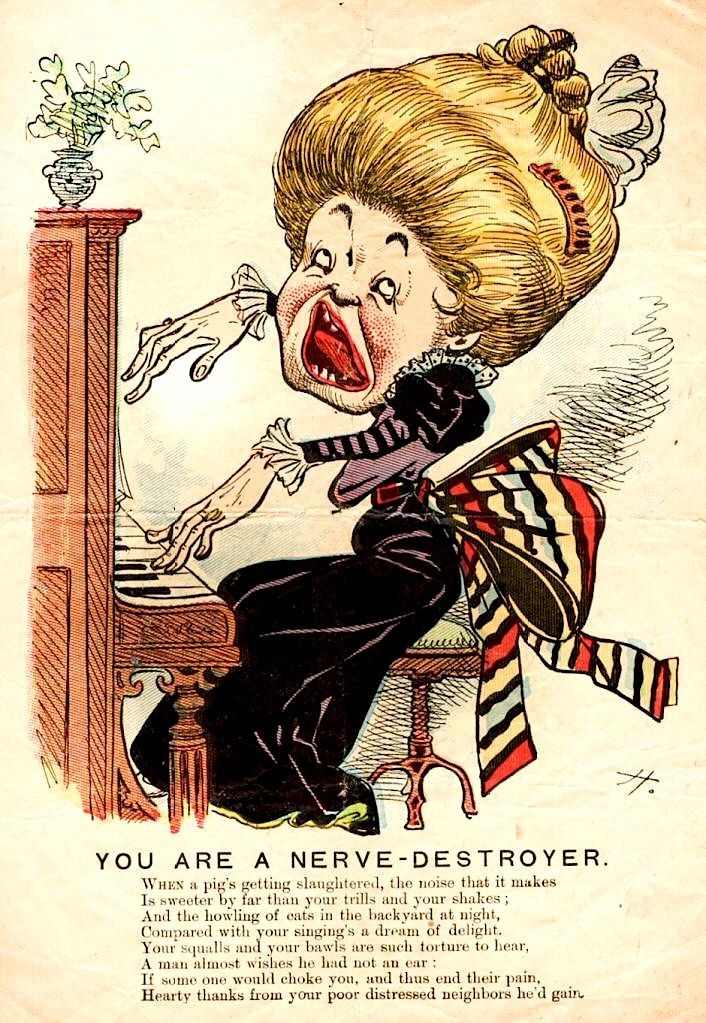

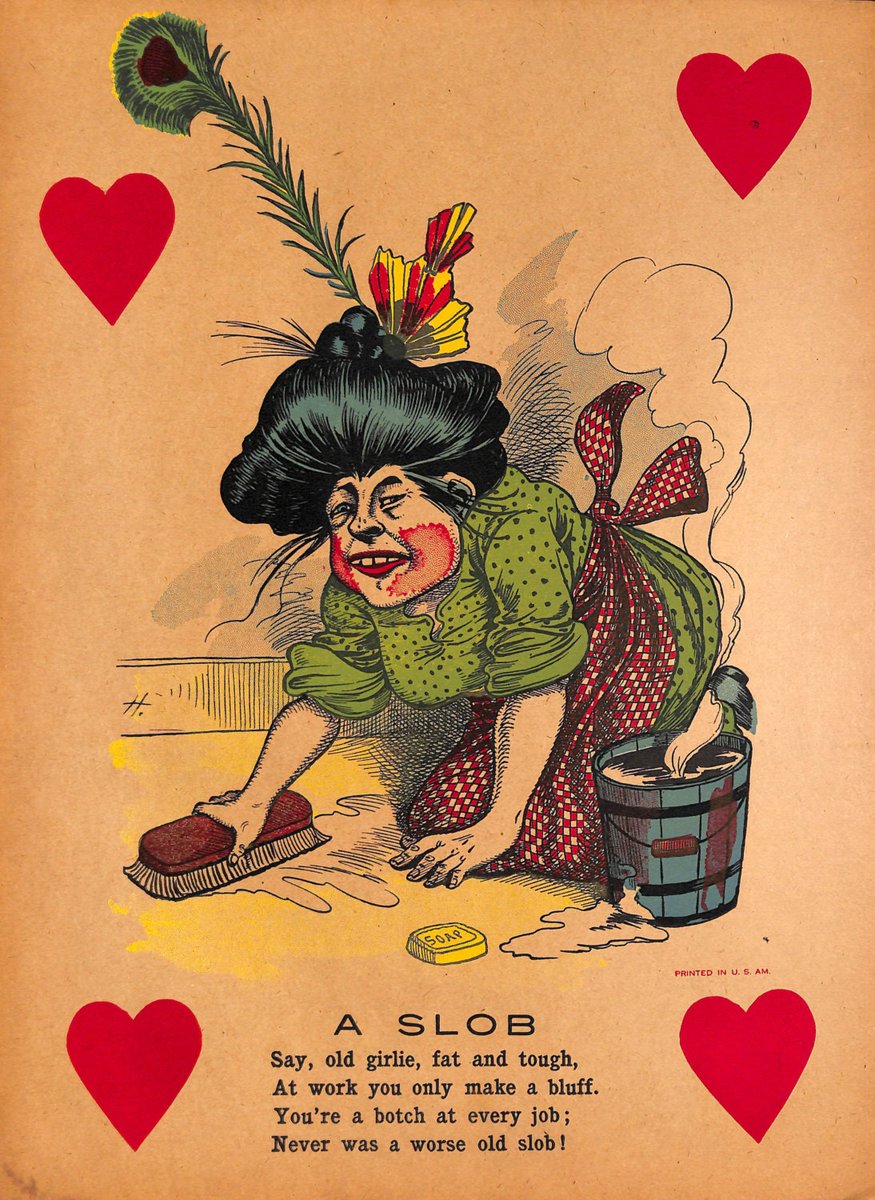

technologies for the mass circulation of pictorial imagery and the development of advanced postal systems.Before they were dubbed vinegar valentines, these sassy cards were known as mocking or comic valentines. Their tone ranged from a gentle jab to downright aggressiveness.

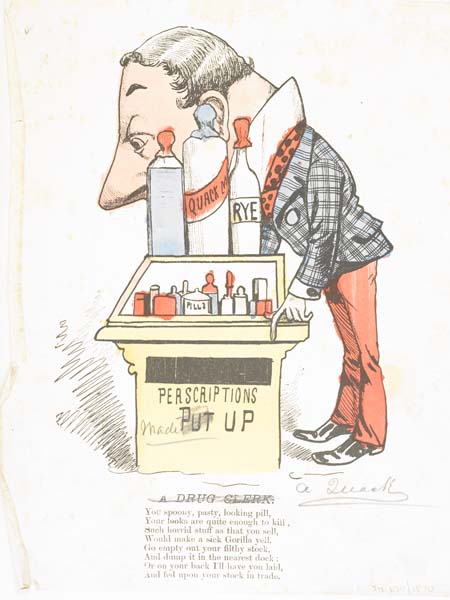

There was an insulting card for just about every person someone might dislike—from annoying salespeople and landlords to overbearing employers and adversaries of all kinds.

Cards could be sent to liars and cheats and flirts and alcoholics, while some cards mocked specific professions. Their grotesque drawings caricatured common stereotypes and insulted a recipient’s physical attributes, lack of a marriage partner or character traits.

By the mid-19th century, both Britain and the United States had large-scale valentine production systems in place. Insulting valentines expanded upon traditional valentines and offered manufacturers an additional source of revenue.

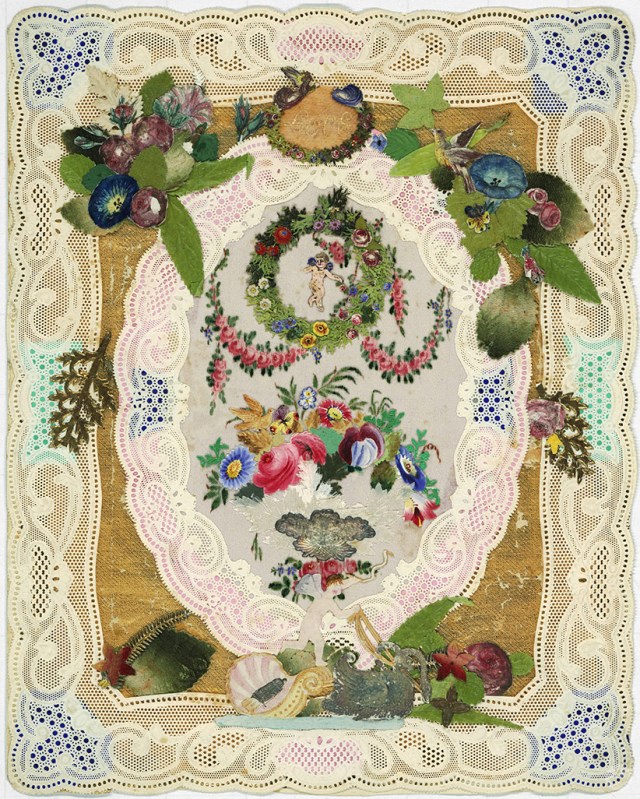

Vinegar cards could be cheaply made by printing them on a single paper, folding and sealing them with a bit of wax. That said, Bradbeer adds that many mass-produced cards of the 19th century involved elaborate hand work in their assembly.

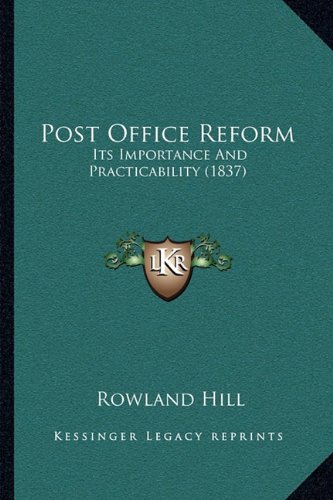

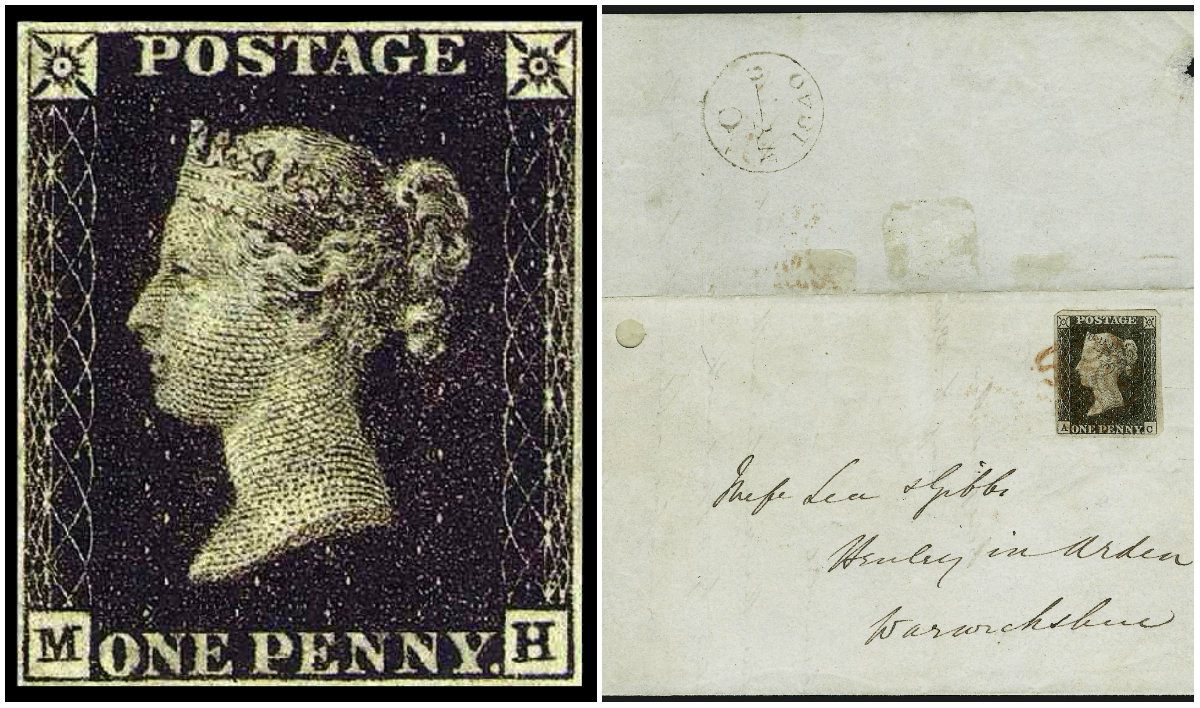

In 1837, a government postal official named Rowland Hill published a seminal pamphlet: Post Office Reform; Its Importance and Practicability.

Britain’s Uniform Penny Post, which allowed anyone in England to send something in the mail for just one penny, went into effect on January 10, 1840. One year later, the public sent nearly a half million valentines.

The number might have been higher, but postmasters sometimes confiscated vinegar valentines, deeming them too vulgar for delivery.Postal workers were not the only ones rattled by their nastiness of vinegar cards.

Less is known about insulting valentines than sentimental ones, in part because very few survived. Most surviving examples are unsent cards found in the collections of printers and stationers.

Because they were mailed anonymously, most senders of vinegar valentines faced few repercussions. Adding insult to injury, senders didn’t even foot the cost of postage.

As a result of some of the extreme reactions and regular letters of complaint in the press, the cards began to fall out of favor.

Whether commercialization or class was the cause of their spread, impassioned pleas to clean up the holiday became more widespread in the later-19th century.

According to legend, an English Valentine received in 1847 by a woman in Massachusetts inspired the beginnings of the American Valentine industry.

Esther A. Howland, a student at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, began making Valentine cards after receiving a card produced by an English company. As her father was a stationer, she sold her cards in his store.

The business grew, and she soon hired friends to help her make the cards. And as she attracted more business her hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts became the center of the American Valentine production.

By the mid-1850s the sending of manufactured Valentine’s Day cards was popular enough that the New York Times published an editorial on February 14, 1856 sharply criticizing the practice:

¡"Our beaux and belles are satisfied with a few miserable lines, neatly written upon fine paper, or else they purchase a printed Valentine with verses ready made, some of which are costly, and many of which are cheap and indecent.

In any case, whether decent or indecent, they only please the silly and give the vicious an opportunity to develop their propensities, and place them,anonymously,before the comparatively virtuous.The custom with us has no useful feature, and the sooner it is abolished the better"

Despite the outrage from the editorial writer, the practice of sending Valentines continued to flourish throughout the mid-1800s.

In the years following the Civil War, newspaper reports indicated that the practice of sending Valentines was actually growing.

On February 4, 1867, the New York Times interviewed Mr. J.H. Hallett, who was identified as the “Superintendent of the Carrier Department of the City Post Office.”

Mr. Hallett provided statistics which stated that in the year 1862 post offices in New York City had accepted 21,260 Valentines for delivery. The following next year showed a slight increase, but then in 1864 the number dropped to only 15,924.

A huge change occurred in 1865, perhaps because the dark years of the Civil War were ending. New Yorkers mailed more than 66,000 Valentines in 1865, and more than 86,000 in 1866. The tradition of sending Valentine cards was turning into a big business.

The February 1867 article in the New York Times reveals that some New Yorkers paid exorbitant prices for Valentines:

"It puzzles many to understand how one of these trifles can be gotten up in such shape as to make it sell for $100; but the fact is that even this figure is not by any means the limit of their price.

There is a tradition that one of the Broadway dealers not many years ago disposed of no less than seven Valentines which cost $500 each, and it may be safely asserted that if any individual was so simple as to wish

to expend ten times that sum upon one of these missives, some enterprising manufacturer would find a way to accommodate him."

The newspaper explained that the most expensive Valentines actually held hidden treasures hidden inside the paper:

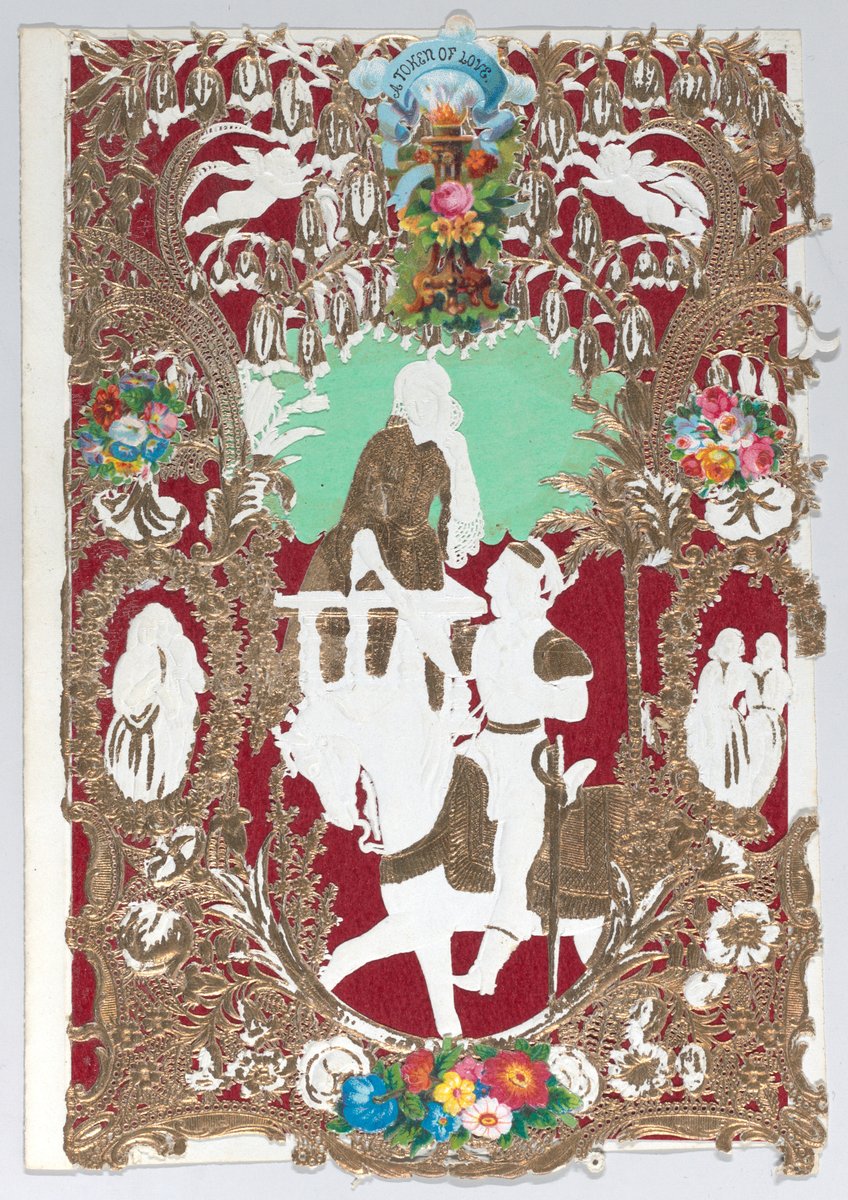

"Valentines of this class are not simply combinations of paper gorgeously gilded, carefully embossed and elaborately laced. To be sure they show paper lovers seated in paper grottoes, under paper roses, ambushed by paper cupids, and indulging in the luxury of paper kisses;

but they also show something more attractive than these paper delights to the overjoyed receiver. Receptacles cunningly prepared may hide watches or other jewelry, and, of course, there is no limit to the lengths to which wealthy and foolish lovers may go."

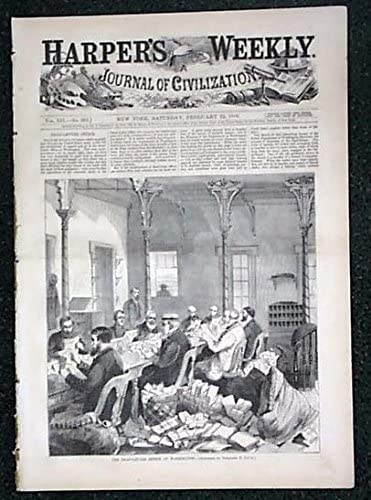

Published in the illustrated newspaper Harper’s Weekly on February 22, 1868, Winslow Homer’s “St. Valentine’s Day - The Old Story in All Lands” equates the modern practice of sending and receiving valentines with the myth of eternal love.

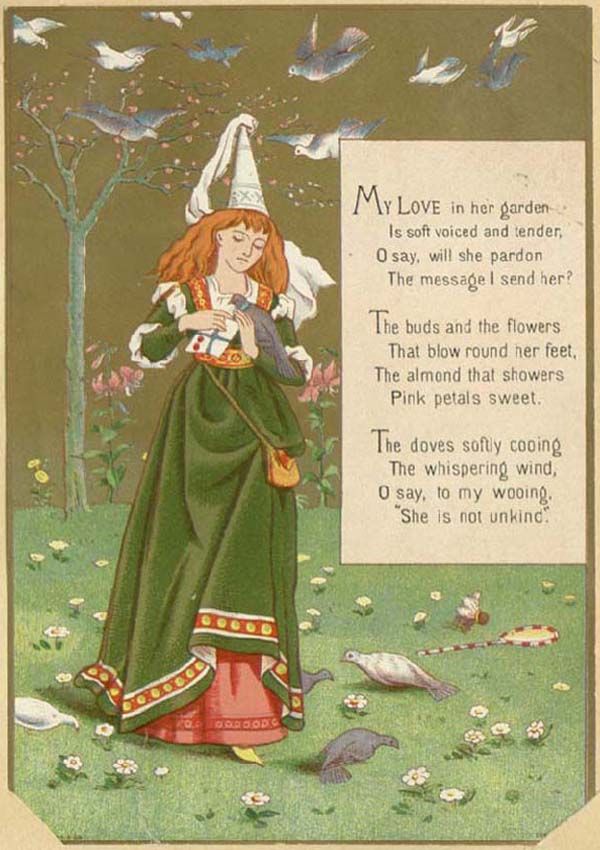

The legendary British illustrator of children’s books Kate Greenaway designed Valentines in the late 1800s which were enormously popular. Her Valentine designs sold so well for the card publisher, Marcus Ward, that she was encouraged to design cards for other holidays.

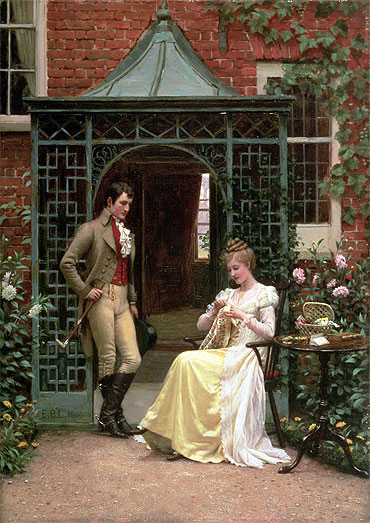

Valentines were often sent anonymously, and a large part of the pleasure of receiving a valentine lay in identifying who sent it, discovering hidden images, solving a riddle, or decoding a message written in the language of flowers.

Whether sent through the mail or handed directly to the recipient, valentines sought to dissolve the boundaries of time and place, in the pursuit of romantic love, friendship, or familial affection.

They formed a powerful communication medium that impacted, and continues to impact, the human heart through their multisensory appeal.

During the late nineteenth century, the occasion of St. Valentine’s Day was a chance for novelty in entertaining.

Valentine’s Day party ideas such as luncheons, teas, socials and fancy dress functions of all sorts were easily and artistically arranged with flowers, hearts, darts and cupids. The success of these pleasant social affairs often depended on the theme of the party.

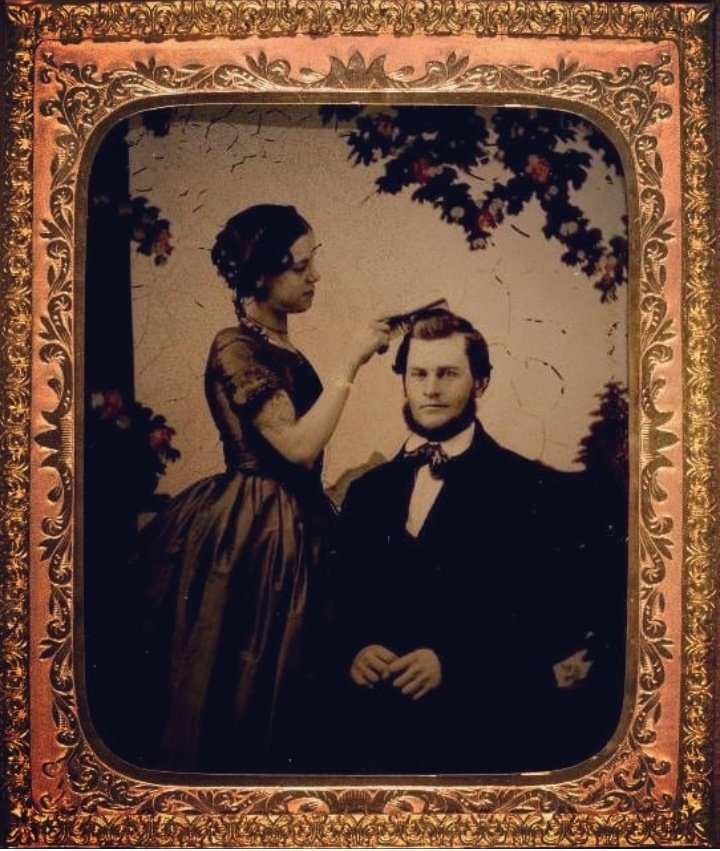

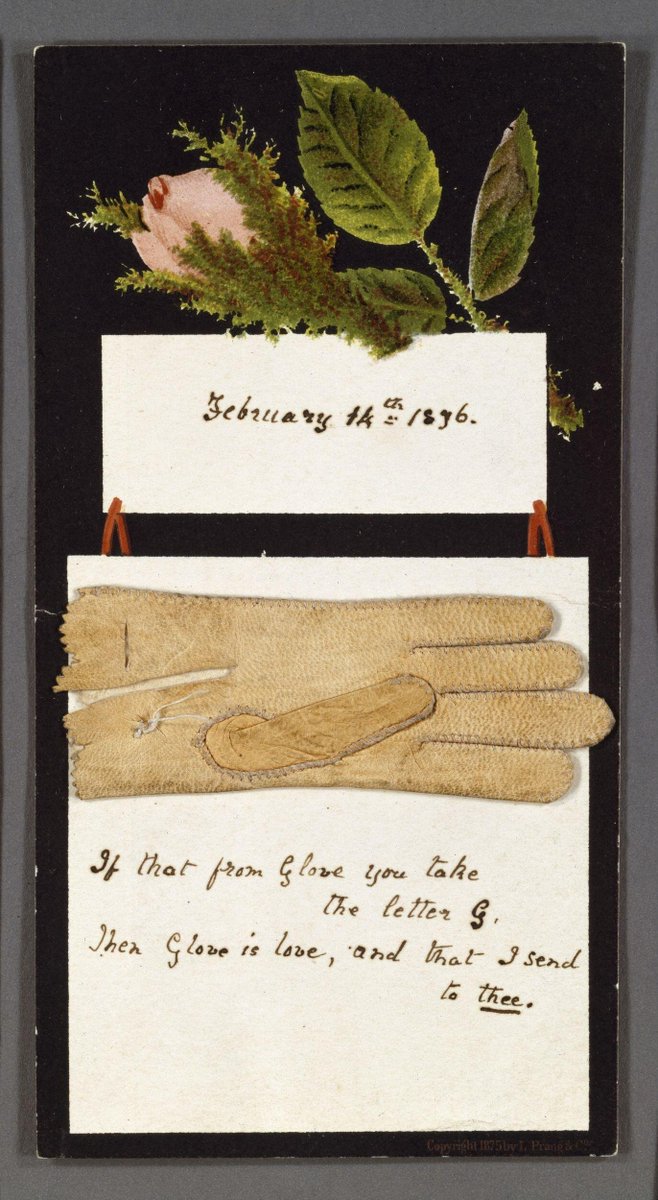

A token of love in the 19th century was a paper hand, which was a symbol of courtship. Tiny paper gloves were also popular. Real gloves had long been a favorite valentine gift, especially in the British Isles were it became a true love token.

With them went verses like this:

"If that from Glove, you take the letter G,

Then Glove is Love and that I send to thee."

"If that from Glove, you take the letter G,

Then Glove is Love and that I send to thee."

Sometimes the gloves was a way of proposing. If the girl accepted, she wore them to church the following Easter.

When and where available, and when financial circumstances made such gifts (and frivolities) possible, newspapers of the day indicate sweethearts (particularly ladies… but gentlemen, too) expected Valentine’s Day gifts from the fellow courting them (or their best gal).

-Silver trinkets

By World War I, the giving of cards (and gifts) on Valentine’s Day had very much declined and hand-crafted cards were a dying art.

Perhaps, because of the war, the giving of cards on Valentine’s Day grew again during the 1920s. The holiday, whose modern traditions are firmly rooted in the Victorian era, continues to grow in popularity to this day.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh