Iron has a very long history in Uganda, as it does in the larger Great Lakes region. For a long time, historians argued that iron smelting-smithing developed first among Bantu statebuilders, offering them an advantage in clearing land, producing food, and organizing war. 1/19

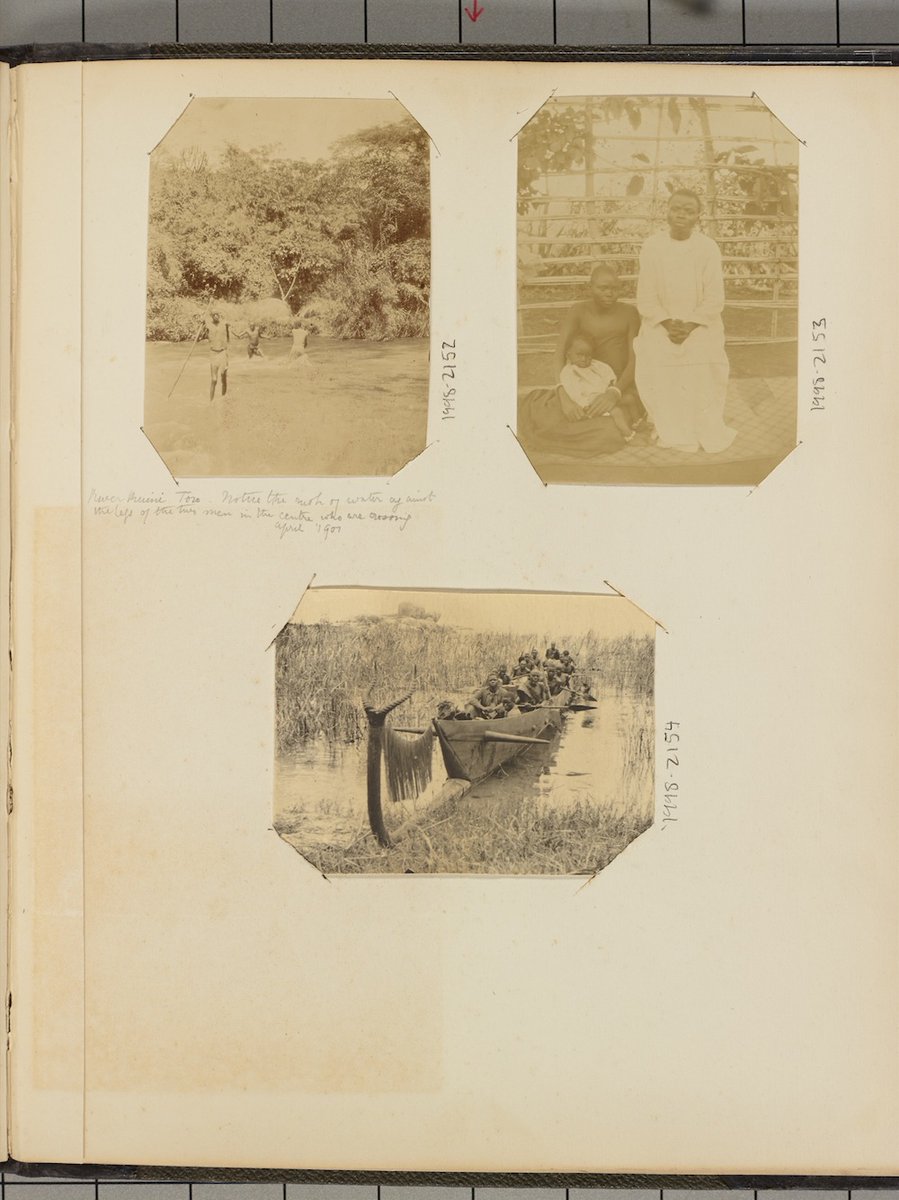

‘Iron Smelting’. Uganda Photographs, c. 1897 – 1903 EEPA 1998-002-0016 Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives National Museum of African Art Smithsonian Institution. 2/19

Much of the existing evidence, though, now shows that Nilo-Saharan communities most likely developed iron-smithing first; later borrowed by Bantu speakers. Archaeological evidence suggests that iron use became common in the interlacustrine region around 500 BCE. 3/19

Cultural & political practices became interconnected with iron smithing—& iron production helped expand regional trade and economies. It also helped create ways of talking about power. As David Schoenbrun notes: “Iron creates meaning when smiths beat a hoe blade into shape. 5/19

Iron expresses power when a leader is buried with knife and axeheads by his side. Iron tells the story of the life cycle and assigns gender to social relations and divisions of labor when a smelter likens the smelting process to that of birth, 6/19

as he makes the furnace into a fertile woman, and (in many instances) as he seeks to keep women capable of bearing children away from the site where he transforms iron ores into his ‘offspring,’ iron bloom.” 7/19

Numerous iron ore sites developed in Bunyoro-Kitara, in conversation w/ northern Ugandans; knowledge then spread to Buganda. By the 1500s, iron became a mechanism around which authority was negotiated between sites of public healing, royal 8/19

capitals, & royal burial shrines. This is why royal burial sites assimilated iron into their burial practices: because it was first important at sites of public healing. Notice the following 2 images, 1 where iron spears are observed at Kabaka Muteesa I’s tomb (taken 1900); 9/19

‘Mtesa's Tomb’. Uganda Photographs, c. 1897 – 1903 EEPA 1998-005-0028 Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives National Museum of African Art Smithsonian Institution. 10/19

I am of the opinion that one of the reasons why A. Mackay attracted followers (abamackai) is because he was seen as a smith in a much longer genealogy of local iron producers and healers. From the very beginning, European relations were deeply grounded in local knowledge. 12/19

There were numerous proverbs that captured the power of blacksmiths; & how iron was used to talk about the competition of claimants to the throne. Some include: "Ekyuma kitya muweesi (Iron, it fears a blacksmith)". And “Kalema ka nsinjo: ekyuma kitema kinnaakyo.” 14/19

Competing ideas about iron did not go away in the colonial period. In the late 1950s, UPC activists in northern Uganda effectively argued that the iron attached to the DP’s hoe symbol was distinctively “Bantu” and not “Nilotic.” 15/19

Notice the DP hoe, and how it mirrors southern designs; as opposed to the design of iron hoes in Lango, Tesoland, and Acholiland. 16/19

The UPC activist, Mr Otim, observed that "the Langi use a spade-like implement and they work with it by making a pushing, rather than a chopping movement." 17/19

Otim continued: "Some people do not like this hoe symbol […] They say it is a Baganda-type hoe. It is not that they do not like the Baganda. But they do not like what the Baganda are trying to do about breaking away from the rest of Uganda." 18/19

In short, hoes were much more than simple tools; they represented longer, much more interesting histories about power, knowledge, and political possibility. 19/19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh