This Day in Labor History: February 20, 1893. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad went into receivership. This was the first step toward the Panic of 1893, the greatest economic crisis in American history prior to the Great Depression! Let's talk about its impact on workers!

The nineteenth century economy was inherently unstable. With a weak central government and lot of hostility to centralized control of the economy, it did not take much to tank the economy. Booms and busts were common.

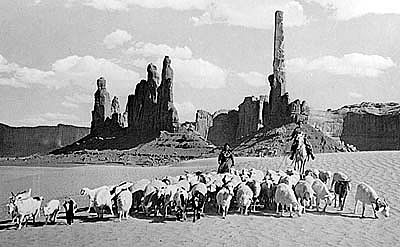

In the post-Civil War era, the railroad was the dominant industry.

Completely transforming the lives of nearly all Americans, they moved goods and people around at unprecedented rates, while also gaining massive control over prices for both farmers and consumers.

The railroad also massacred people in the streets of cities due to poorly maintained tracks without safety, controlled the coal industry, and engaged in speculations that were as poorly regulated as they were considered.

Jay Cooke’s railroad speculations led to the Panic of 1873 and the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 was more of a public rebellion against the railroads’ domination over working-class lives than an organized union movement.

The Hayes administration’s choice to use the military to violently suppress the movement spoke of the belief that this was an internal insurrection; certainly the language used by the railroad barons, media, and politicians suggested they saw it this way.

The railroads continued to dominate workers’ lives in the aftermath. By the 1880s, this was leading to the growth of the Farmers’ Alliances and Populist movements in rural America, while unions made organizing them a major focus.

The railroad brotherhoods were limited because they were elite workers who refused to organize on an industrial scale, but they still mattered.

The Knights of Labor initially made a lot of progress organizing the railroads, defeating Jay Gould in an 1885 strike.

But the vile capitalist struck back during the Great Southwest Strike of 1886, just as the Knights crested and then it crashed on the rocky shoals of employer extremism and its own unwillingness to act as a modern labor union.

There were several reasons for the Panic of 1893, all revolving speculation in a poorly regulated economy.

Argentine political instability combined with European wheat speculation over a failed harvest to create a crisis point, which led to banks pulling gold from the U.S. Treasury. This certainly contributed. But the continued railroad speculation put the economy over the top.

The Philadelphia and Reading collapse was followed shortly by another major company, the National Cordage Company. Panic erupted on the stock market by July. Bank runs followed and so did bankruptcies and layoffs.

Fifteen thousand businesses shuttered their doors. The Union Pacific, Northern Pacific, and Santa Fe Railroad all declared bankruptcy, among the 74 railroads that failed. 600 banks closed

Cleveland blamed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and while that law wasn’t the soundest economic policy, it did basically nothing to solve the crisis. The nation had vastly overbuilt its railroad infrastructure.

As Richard White points out in Railroaded, the post-Civil War railroad boom was a comedy of errors, a house of speculative cards that collapsed repeatedly, where railroads were built for no good reason as there was no market, and yet they continued to be built and built.

The unemployment rate skyrocketed.

While good economic numbers are a little bit of guesswork in the 19th century, one good estimate has unemployment at 3 percent in 1892, 11.7 percent in 1893, and an unbelievable 18.4 percent by 1894, stabilizing after that at 13-14 percent until 1899.

But in many cities, unemployment was in the 20-25 percent range or even higher in single-industry cities. Steel towns were especially decimated, so cities in the Pittsburgh area may have had over 1 in 2 workers unemployed.

So this was nearly a decade of very hard times for workers. It showed. The Pullman Strike the next year came directly out of this for instance.

In that case, George Pullman, owner of the Pullman Sleeping Car Company and his own company town that he ruled as a fiefdom, reduced the wages of workers without reducing the rents he charged in his company town.

This led the workers to go on strike, Eugene Debs’ American Railway Union to issue a boycott of Pullman cars in solidarity, and the Cleveland administration to send out the military to open the railroads.

Pullman was deeply criticized in the public for refusing to be flexible, but he believed in the iron law of profit. He argued he was being flexible because he was only receiving about 3 percent yearly in profit from his housing rather than 6 percent he thought he should get.

Meanwhile, the actual impact upon workers’ lives was irrelevant for people such as Pullman or Richard Olney, Cleveland’s attorney general who was still doing work for his railroad friends while in office and who pushed to deploy the military.

This all spawned many other movements. Jacob Coxey, an Ohio businessman, started an unemployed march to Washington to protest the lack of federal response.

A freaked out Cleveland administration had Coxey arrested on spurious charges of trespassing on the congressional lawn.

Workers in Colorado and other western mining states went on strike and sometimes even won.

The Populists took over the Democratic Party from the Cleveland capitalists, much to the president’s dismay.

the Democrats would never be the same, even if this moving toward a limited white male economic populism, it would never be the party of Cleveland and Olney again. In fact, Democrats lost an unprecedented 116 seats in the 1894 midterms.

While railroads would never play such an outsized role in the American economy as between 1870s and 1890s, it would take decades of continued financial booms and busts for the government to take both regulation and the need to ensure a decent life for the working class seriously.

Back Monday to talk about the 1860 Lynn shoemakers strike

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh