Up bright & early for today's stroll through the capital: a tour of Roman London. We shall walk the line of the city walls, and then visit the sites of its vanished monuments. (The archaeological sites, alas, will be shut, but there is always the imagination...) #Londinium

London, unlike most provincial capitals, was a purely Roman foundation. It emerged as it did for the same reason it has always been the greatest city in Britain whenever the southern lowlands are under a unitary authority: it is where the Thames is both navigable & bridgeable.

What did Londinium look like? This is the only known Roman portrayal of the city: a celebration of the recapture of Britain from rebel warlords by Constantius Chlorus, father of Constantine the Great. We know it's London because the letters LON appear below the kneeling figure.

A huge part of the fascinatinon of Roman London for any apocalyptically-minded Londoner is to contemplate the (relative) emptiness that preceded it, and the abandonment that claimed it as the city went into decline in the 4th century, & then precipitous decline in the 5th.

“And this also,” said Marlow suddenly, “has been one of the dark places of the earth.”

Conrad's famous novella on the heart of imperial darkness in the Belgian Congo begins on the Thames, with a haunting evocation of a centurion sailing up the estuary during the Roman conquest.

Conrad's famous novella on the heart of imperial darkness in the Belgian Congo begins on the Thames, with a haunting evocation of a centurion sailing up the estuary during the Roman conquest.

"Imagine him here—the very end of the world, a sea the colour of lead, a sky the colour of smoke, a kind of ship about as rigid as a concertina—and going up this river with stores, or orders, or what you like. Sand–banks, marshes, forests, savages..." #Londinium

To tour Roman London is also, in a psychogeographical manner, to tour the London of the Victorian & Edwardian imagination - & the imaginings of earlier periods too. Christopher Wren, John Stow, Geoffrey of Monmouth: all were haunted by the vision of London as an ancient city.

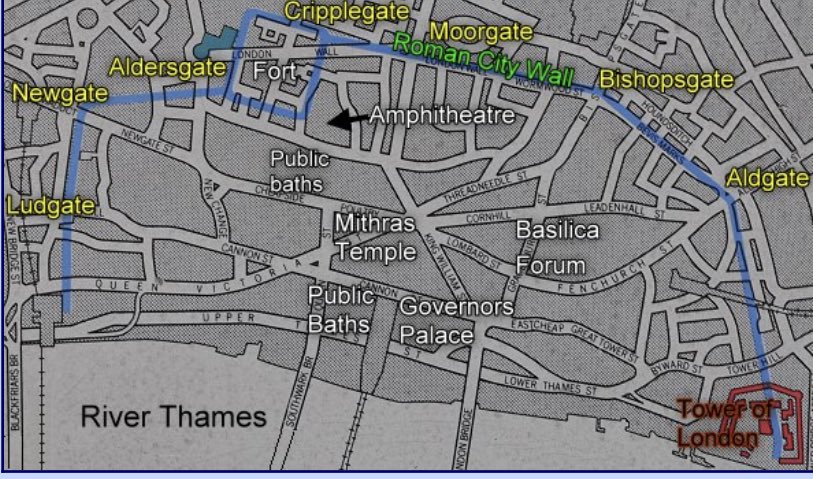

And so we approach the City. The view from here in Roman period would have been of Londinium: the walls, the temples, the basilica, the fort. The Roman street plan has been largely erased, but the line of the wall can still be traced, & the gates are still there in the toponyms.

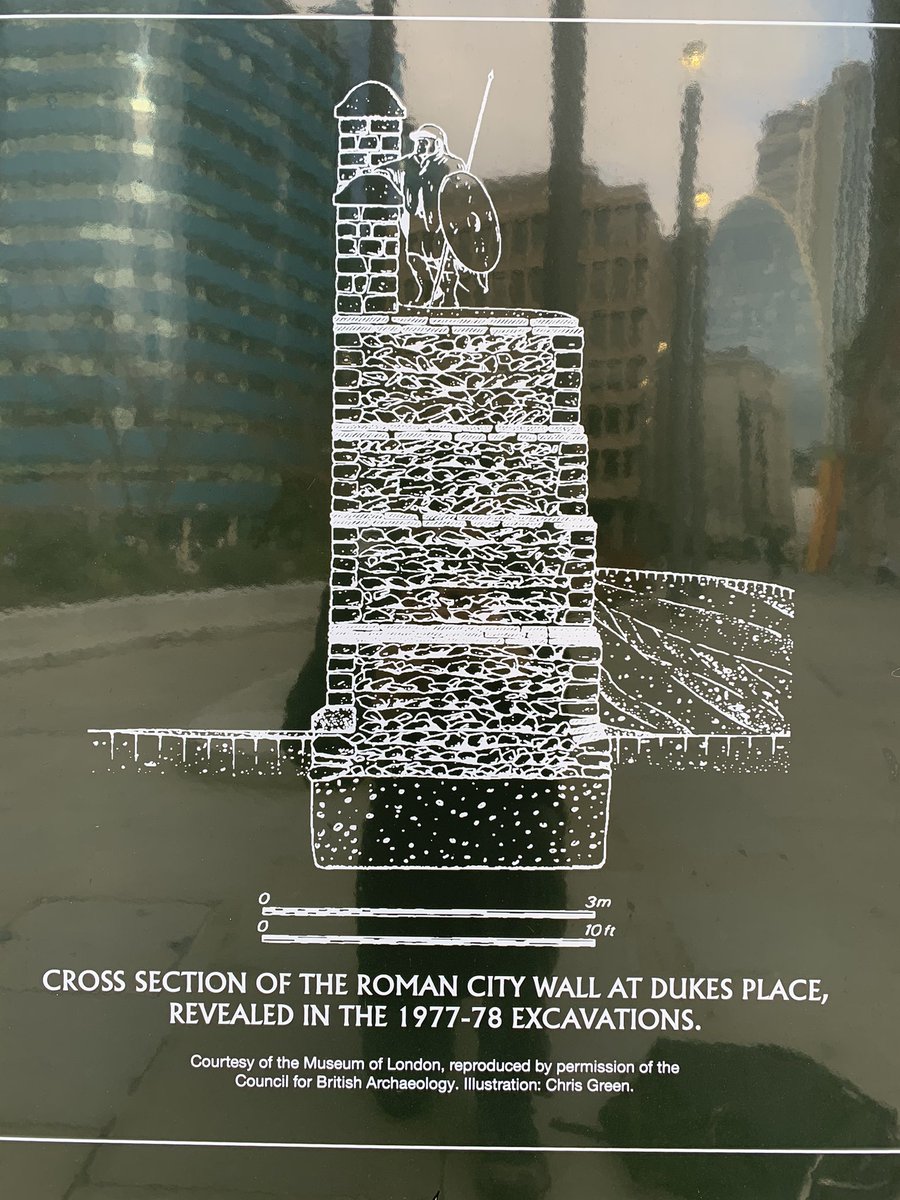

The wall around Londinium was built in the late 2nd or early 3rd C (most probably by Clodius Albinus), and continued to be added to almost until Roman Britain came to an end. Its sheer scale made it one of the most impressive construction projects in the entire province.

The Roman wall on the west edge of Londonium met the Thames beside what is now Blackfriars Stan. In the 4th C, a further stretch was built along the river bank. It collapsed in the 11th C. “The fishfull river of Thames with his ebbing & flowing, hath long since subverted them.”

At Ludgate, the Roman wall was rebuilt in the reign of Edward I to incorporate the Dominican priory (‘Black Friars’), which was begun in 1284, using Roman building material. Church Entry preserves a ghostly hint of the path that once led between the nave & chancel.

The west wall of St Martin Ludgate stands above the line of the Roman wall. When the church was rebuilt by Wren after the Great Fire, workmen discovered the tombstone of a centurion, Vivius Marcianus, which had been used in the building of the original medieval church.

Ludgate itself, according to the ever reliable Geoffrey of Monmouth, was built by “king Lud a Briton, about the yeare, before Christs nativitie 66”. John Stow, who reports this, acknowledges there “hath been some question among the learned” about the accuracy of Geoffrey’s info.

Newgate – despite its name, & Stow’s claim that it had been built in the reign of Henry I or Stephen – was in fact the Roman gate that led from Londonium onto the westward stretch of Watling Street.

Stretches of the Roman Wall around Newgate have been preserved under an extension to the Central Criminal Court and in a basement under Merril Lynch’s London HQ (this basement also boasts a medieval bastion). A hint of the Roman is preserved on the street name off Newgate...

The Roman wall ran across what is now Postman’s Park, where the memorial to “heroic self-sacrifice,” instituted by the artist George Frederick Watts in 1900, commemorates deeds that might have graced the pages of Livy.

Aldersgate was another Roman gate, so called – as Stowe puts it – “for the very antiquity of the gate it self.” (Though actually it was not one of the original gates, having been added c. 350)

Barbican stands on what was originally a ‘barbecana’, a Roman watchtower to the north of London’s Roman fort. Built c. 120, 80 years before the city wall was built, the fort housed some 1000 soldiers. The early modern walls here are built in Roman foundations.

Cripplegate was the northern entrance into the Roman fort. Its name, according to Stow, derives from the “Criples begging there.” The reconstruction shows it as it might have appeared c. 900

This stretch of the medieval wall (featuring the only surviving example of the brick parapet added in 1477) was built on a lower layer provided by the wall of the Roman fort.

Cripplegate Bastion - 13th century, & very eerily situated today - marks the position of the north-west corner of the Roman fort.

John Milton - the English Virgil - is buried in St Giles-without-Cripplegate, just beyond it...

John Milton - the English Virgil - is buried in St Giles-without-Cripplegate, just beyond it...

The only subterranean stretch of the Roman wall open to the public during lockdown is to be found here: bay 52 of the London Wall car park.

All Hallows on the Wall (83 London Wall) – built in the 1760s - was, at its name suggests, built directly on the line of the Roman wall. The curve of the church’s north wall follows the line of a Roman bastion.

Bishopsgate guarded the exit from Londinium onto Ermine Street, which led northwards to Lincoln and York. It was rebuilt in medieval times, and finally demolished in 1761.

Houndsditch gets its name from the large number of dead dogs dumped into the ditch that ran alongside the line of the Roman wall. Bevis Marks, the oldest extant synagogue in Britain, opened on the line of the wall in 1701.

Aldgate, which opened onto the road to Colchester, survived in its Roman form until the 11th century. Rebuilt several times, it was where Chaucer lived from 1374 to 1386, in apartments above the gate itself. (His grandfather had been murdered there in 1313)

On Jewry Street, next to the appropriately named Centurion House, a portion of the Roman wall is preserved in the cellars of the Three Tuns. Alas, there’s no seeing it today...

A stretch of the Roman wall just north of the Tower, which survived because it had been incorporated into a warehouse in 1864.

The best stretch of the Roman wall is by Tower Hill tube & boasts - not entirely appropriately, a statue of Trajan: an emperor who never visited Britain. The other 2 emperors to have public statues are Constantine (outside York Minster) & Nerva (outside Gregg’s in Gloucester)

Cast of an inscription now in @britishmuseum, commemorating Julius Alpinus Classicianus, a Gaul appointed to serve as procurator in Britain after the Boudicca revolt. He died in London, & portions of his tomb were much later incorporated into a medieval projecting tower here.

Memorial to a teenage girl who died 350-400 AD & whose grave was found during the construction of the Gherkin. The plaque marks her reburial. Rose petals were scattered on her memorial.

Londinium’s basilica, built in the first 3 decades of the 2nd century, was at the time of its construction the largest Roman building north of the Alps. All that remains is a brickwork pier in the basement of this hairdressers in Leadenhall Market (photo from an earlier visit).

We head for the river Walbrook. London was founded in the river valley that stretches between Ludgate Hill & Cornhill. The Walbrook flowed through the centre of Londinium, & - fortunately for us - was used by the city's inhabitants as a dumping ground for all kinds of rubbish.

When James Stirling’s No 1 Poultry was built in the 90s, traces were found by archaeologists of charred buildings left by Boudicca, a temple on the banks of the Walbrook, & 48 skulls, all of young men.

The London Stone - which in the Middle Ages was believed to have been set up by Brutus the Trojan - was most likely Roman. It seems originally to have been situated on the north-south axis of a huge structure generally thought to have been where the governor was based.

London’s mithraeum, found in 1954, was moved first to an open spot, complete with 60s-style crazy paving, & then very recently again, into the bowels of the Bloomberg Building - a vast improvement.

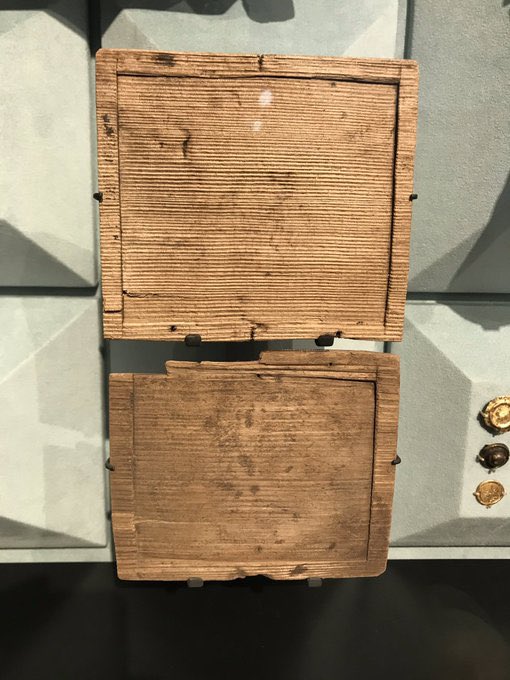

The line of the Walbrook. It is thanks to the river that so much organic material from Roman London has survived, redeemed from its damp soil & now presented in the Bloomberg Space, directly above where the river flows: doors, sandals, writing tablets, nit combs...

Perhaps the single most evocative find was an IOU, which can be dated to 8 January AD 57 - 3 years before London was incinerated by Boudicca. It shows that the city was already set on the course it remains on to this day: ££££

The last stop of our tour of Roman London - the city’s amphitheatre, which lies beneath the Guildhall- is even more off limits than the other subterranean relics of Londinium: it’s being used for COVID testing. An appropriately 2021 way to end our walk...

Back home, & a reminder for anyone who might fancy doing this walk, there will be lots more to see when the lockdown ends. The Mithraeum, the amphitheatre, traces of the Roman wall and basilica - all at the moment lie locked away.

So too, of course, do the finds from Roman London that are preserved in @MuseumofLondon & @britishmuseum.

Finally - a shameless plug - @dcsandbrook & I will be releasing an episode of @TheRestHistory tomorrow (Monday) morning on the theme of 'empire'. The Roman variant features prominently...

PS For those wondering - here’s the magnificently situated statue of Nerva in Gloucester

https://twitter.com/holland_tom/status/1277854634455990272

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh