The oldest depiction of the Book of Esther was discovered in the synagogue in Dura Europos, destroyed in 256 CE in the war between the Romans and the Sasanians.

The synagogue offers precious insight into the dynamics of Jewish communities on the Roman-Sasanian frontier.

🧵

The synagogue offers precious insight into the dynamics of Jewish communities on the Roman-Sasanian frontier.

🧵

While the war led to the tragic abandonment of Dura, it also meant that the city laid untouched for millennia. The synagogue paintings were preserved precisely because the synagogue comprised part of the city wall, and it was reinforced with sand during the extended siege.

In this image of the painting program, you can see the height and position of the sand used to reinforce the wall based on what it preserved.

Given that the city was largely untouched, we have a pretty comprehensive sense of the layout of the urban landscape. Notice how the synagogue appears on the same path as the Temple of Zeus and of Aphiad, a Mithraeum, and a so-called "Christian building."

Some of the art in the Christian building was also preserved, and reflects the common artistic idiom of the time and place.

Compare, for instance, the image of Samuel selecting David from amongst his brothers with the image of Konon and his family at the Temple of Bel.

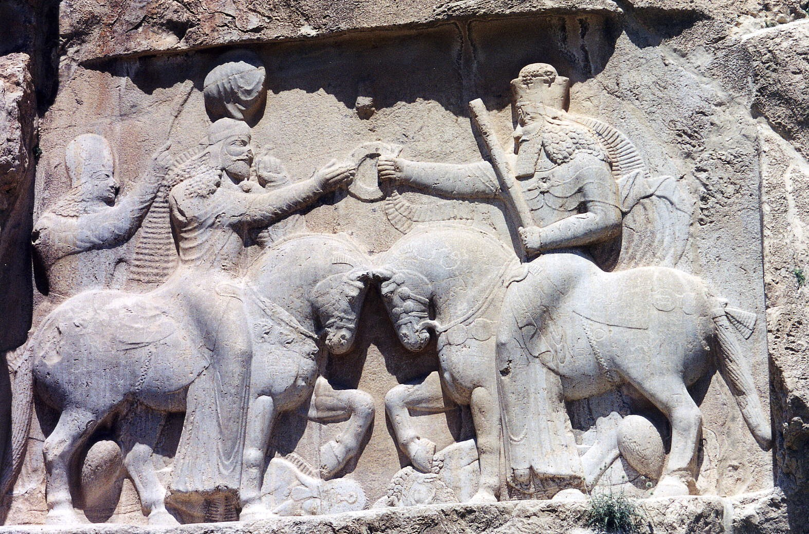

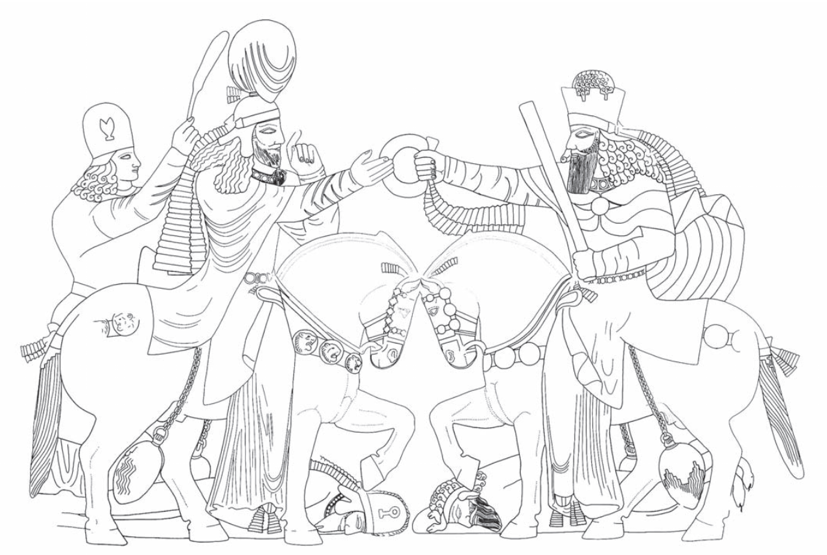

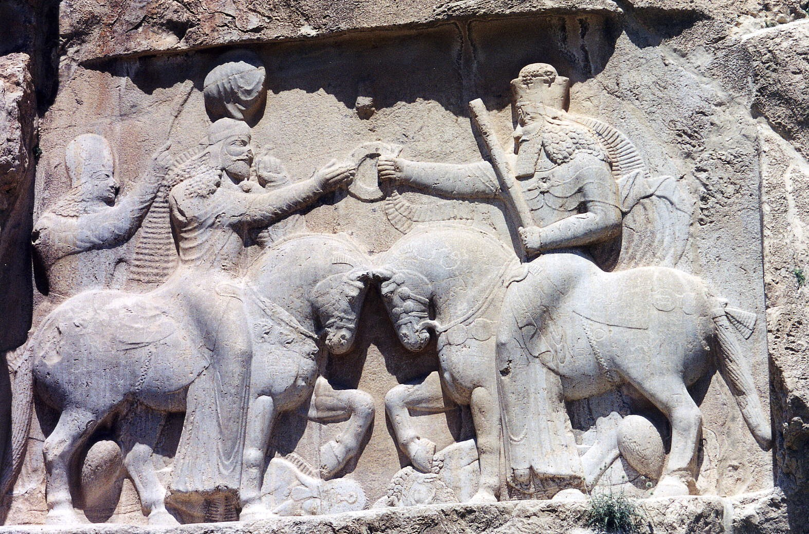

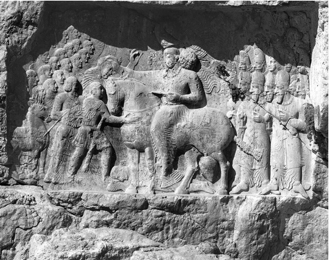

Back to the Esther panel: it depicts the events of Esther 6, where Haman must honor Mordechai at the behest of the king, who sits flanked by Esther. These characters are all identified with short inscriptions. Notice how Haman wears a short tunic with no trousers & is barefooted.

Fascinatingly, the synagogue paintings included six Middle Persian graffiti left by Persian scribes and officials that recorded their favorable impressions of the art, most of which appear on the Esther panel. It seems likely that they were told and enjoyed the story of Esther!

Dura offers a glimpse into the life of a city on the Roman-Sasanian frontier in the early CE. Jews appears to have been well-integrated, shared artistic conventions, constructed a synagogue on the same street as other temples, & welcomed Persian officials to admire their art.

Fin

Fin

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh