I’ve been reading a bunch of absolutely fascinating stuff about the history of disaster relief funds lately, so I thought I’d share some of what I have learned, in a THREAD.

Or, in fact, two THREADS.

As I think even by my standards this would be overly long to do in one....

Or, in fact, two THREADS.

As I think even by my standards this would be overly long to do in one....

If you like tales of

DONOR MOTIVATIONS!

POWER DYNAMICS!

MODERN RELEVANCE!

CHARITY HISTORY!

Then strap in…

(And if you don’t, TBH you should consider unfollowing me).

DONOR MOTIVATIONS!

POWER DYNAMICS!

MODERN RELEVANCE!

CHARITY HISTORY!

Then strap in…

(And if you don’t, TBH you should consider unfollowing me).

So let’s start with the collection side of things. I.e. getting the money in.

First thing to say is that setting up charitable funds in response to specific disasters is a major feature of the history of charity (and has arguably played a key role in shaping its development).

First thing to say is that setting up charitable funds in response to specific disasters is a major feature of the history of charity (and has arguably played a key role in shaping its development).

As Field notes in a great paper about the fund (or “brief”) set up in response to the 1666 Great Fire of London, such funds were a commonplace response to fires (which themselves occurred regularly).

The establishment of new disaster relief funds remained a regular occurrence in later centuries.

Some were in response to major events, such as the Lancashire Cotton Famine of 1861-65:

Some were in response to major events, such as the Lancashire Cotton Famine of 1861-65:

But there were also many funds formed in response to other, more minor disasters (of which there were plenty):

One particularly prevalent category of relief funds in the C19th were those set up in response to colliery disasters, as you can see from this list (taken from Benson):

And these continued into the C20th, as mining continued to be a major part of the UK’s industrial wealth (but often sadly lacking in anything approaching health and safety measures):

Now, when it came to fundraising in the C19th, as David Owen notes, it was often easier to get people to give in response to disasters than to engage them in longer term support for causes.

A phenomenon I’m sure many modern fundraisers would recognise...

A phenomenon I’m sure many modern fundraisers would recognise...

But this wasn’t left to chance either.

Those who fundraised for disaster relief knew all too well the power of social information & peer pressure to encourage/shame people into giving:

Those who fundraised for disaster relief knew all too well the power of social information & peer pressure to encourage/shame people into giving:

This might be for relatively small local disasters, but they would often still take out adverts in national newspapers like The Times to publish donor lists.

Like this one for the Padstow Lifeboat disaster in 1867:

Like this one for the Padstow Lifeboat disaster in 1867:

It might also be for major disasters, like the aforementioned Lancashire Cotton Famine, where the subscriber list is like a Who’s Who of the great and the good of late C19th England.

The support of notable figures was important in driving further donations to a fund, so these kinds of “leadership gifts” were eagerly sought (and publicised):

Conversely, there was social stigma attached to failure by the elite to give to a relief fund in their local area.

As highlighted here in Norwich in 1912, where Colmans (of mustard fame) were visibly big givers but other business were felt not to have pulled their weight:

As highlighted here in Norwich in 1912, where Colmans (of mustard fame) were visibly big givers but other business were felt not to have pulled their weight:

But fundraising for disaster relief was far from limited to local donors. For major disasters (and even for smaller ones) donations often poured in from all around the world (often due to colonial links of some kind):

In an 1862 update on the progress of the Lancashire Cotton Famine Relief fund, for example, the Times carried details of funds raised as far afield as Hong Kong and Halifax, Nova Scotia:

One key factor in determining the fundraising success of a disaster relief fund was the perception of the disaster and the potential recipients.

E.g. in the case of the Great Fire of London dislike of London’s prominence may have played a part:

E.g. in the case of the Great Fire of London dislike of London’s prominence may have played a part:

When it came to colliery disaster funds, it was clear that fundraising efforts were more likely to be successful if those affected were portrayed as stoical, heroic pillars of the working classes rather than emphasising their need:

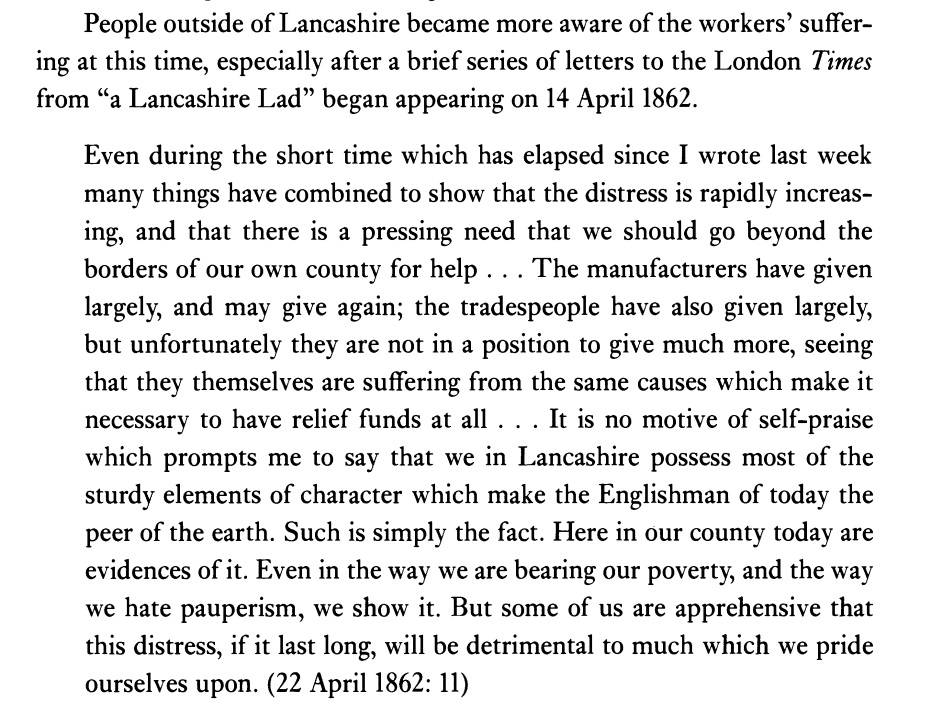

In the case of the Lancs cotton famine, a key turning point in bringing in more funds was the publication of a series of letters in national newspapers from “A Lancashire Lad”, which painted a compelling picture of a dignified, uncomplaining yet needy northerner:

In terms of perceptions of disasters themselves, in some cases they weren’t even deemed sufficiently saleable to merit a public appeal:

In other cases, even where a disaster itself clearly merited a fund there might be other competing disasters that made it harder to raise donations:

Right, that’s enough on the collection side.

In Part 2 of the thread we’ll take a look at some of the issues raised by the distribution of funds.

As you might expect, that’s where things get a bit fruity. So stay tuned...

In Part 2 of the thread we’ll take a look at some of the issues raised by the distribution of funds.

As you might expect, that’s where things get a bit fruity. So stay tuned...

FYI here's part 2 of this uber-thread for ya:

https://twitter.com/Philliteracy/status/1365338644471504898?s=20

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh