Today in pulp... I search for the origins of life itself and the last universal common ancestor!

This is a highly complicated and scientific topic, so it is therefore best explored through the medium of gifs...

This is a highly complicated and scientific topic, so it is therefore best explored through the medium of gifs...

Now there's no universally agreed definition of life: even Erwin Schrödinger was uncertain what it was. But an ability to resist entropy, to reproduce, to mutate, to have a metabolism and to self-organise feature in most definitions.

And whatever life is we reliably assume it's all interlinked in some way. We still use the medieval idea of a 'tree of life' to map the connections, and currently scientists believe this tree has either two or three fundamental branches.

Bacteria and archaea form two of these fundamental branches: both are simple single-cell organisms that usually lack organelles, but their ribosomal RNA is very different. They also form the bulk of the biomass on the planet.

Eukaryotes are different: they have membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria and form multicellular organisms such as you and I.

So did they evolve from archaea, or are they a third fundamental branch of the tree of life?

So did they evolve from archaea, or are they a third fundamental branch of the tree of life?

Views vary on this, and it's due to horizontal gene transfer. You don't just inherit your genes from your parents, you can also swap them with your neighbors! That's how bacteria share antibiotic resistance, and viruses can help it happen.

But it also complicates the tree of life, making it hard to tease out who was related to whom in our prehistory based on gene sequencing. Maybe it's best to talk about a mosaic of life instead of a tree.

This hasn't stopped biologists trying to discover LUCA: the last universal common ancestor of all living things. Gene analysis of multiple bacteria and archaea suggest there are 355 common protein clusters across all life, which give us clues as to what LUCA may have looked like.

LUCA was possibly an anaerobic organism that lived in ocean hydrothermal vents, places rich in H2, CO2 and iron. The energy gradient between the warm vent and surrounding colder water allowed LUCA to make adenosine triphosphate - the molecule that allows energy transfer in cells.

This means LUCA, like a virus, was an organism on the edge of life. It possibly had no cell membrane and relied on iron to form its boundaries. LUCA was a fizzing undersea rock using its unique environment to create energy. Possibly.

The ability for organisms to generate their own energy gradients evolved later on, allowing life to break away from the vents on at least two occasions – one giving rise to the first archaea, the other to bacteria.

But the story has one big plot hole...

But the story has one big plot hole...

It's based on working backwards from organisms that currently exist. What about the extinct ones? Plus LUCA is still a complicated organism. How did this complexity come about? What was before LUCA?

Well in 1992, in a water tower in Bradford being tested for Legionnaires disease, scientists found an amoeba which contained a starting secret...

It was infected with a giant virus!

It was infected with a giant virus!

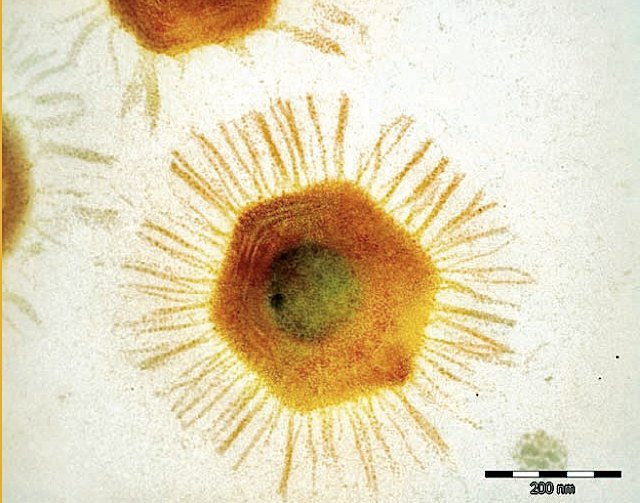

Viruses are normally small, but Mimivirus - as it came to be known - was a monster. It was big enough to be seen under a normal microscope and its genome was far bigger than it needed to be for a virus, with almost a thousand protein-coding genes.

Since 1992 a number of other scary sounding giant viruses - Pandoravirus, Megavirus etc - have been found. Stranger still these can themselves become infected by other, simpler viruses. So what's going on?

Well there are two theories about giant viruses. One is they grew from simpler viruses by capturing DNA from host organisms. They may be huge but that's just accidental; their big genome doesn't really mean anything.

The other theory is they evolved from complicated organisms which lost their ability to reproduce themselves. What's fascinating is that these initial organisms may not have been bacteria or archaea - instead they may have been earlier types of life which are now extinct.

The good news is that giant viruses only attack amoebas. But are they evidence of a lost fourth domain of life? Many are skeptical, but the more examples we find the more we learn about the earliest life on Earth and how it may have developed.

More biology another time...

More biology another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh