In the Ottoman Empire, commentaries on Persian works such as the Gulistān of Saʿdī or the Dīvān of Ḥāfiẓ, besides providing a comprehensive guide to canonical works of literature, offered the non-native speaker a course in the Persian language.

Accordingly, orientalists who studied and collected manuscripts in the Ottoman Empire used Ottoman commentaries and translations as a way of learning Persian. There’s a good example of this in Oxford...

where we find a seventeenth-century orientalist annotating across multiple manuscripts as he tried to work out both Saʿdī’s text and the basic structure of the Persian language.

In the Bodleian’s Laudian collection, we find a copy of the Gulistān (ms Laud 121) with Latin glosses in graphite through the first pages.

Dating annotations is always tricky, but comparing the glosses to Gentius’s Latin translation, published in 1651, offers a solid terminus ante quem—the reader didn’t use Gentius—and the note on the bottom of the first page gives a clear starting point: 1637.

In fact, the reader was probably the individual who bought the book for Laud: Edward Pococke. Pococke collected manuscripts in Aleppo and Istanbul, and was one of the most advanced Western European Arabists of the seventeenth century.

Pococke is actually noteworthy for his relative disinterest in Turkish and Persian, but here we find him trying to learn the latter. Looking at the notes in Laud 121, there’s a clear sign that he was a beginner: he recorded the infinitive forms of verbs alongside his glosses.

But if he’s a beginner, how is he reading the text? Another Bodleian manuscript offers an answer. On the margins of this manuscript, an Arabic commentary on the Gulistān (ms Seld. Superius 75), we again find Pococke’s annotations through the first part of Saʿdī’s preface.

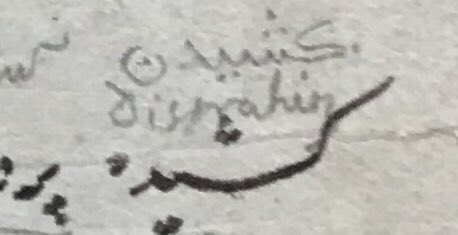

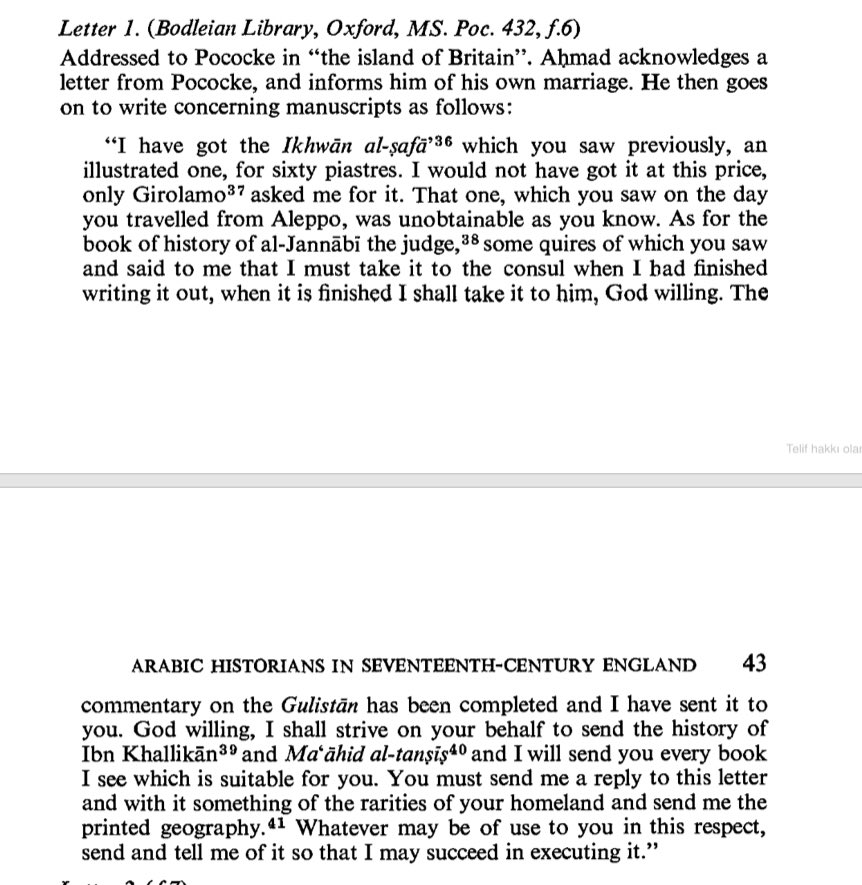

While the scribe of this second ms isn’t named in the colophon, we can identify him as Aḥmad al-Gulšānī, who taught Pococke in Aleppo and bought mss for him. This copy is likely the Gulistān commentary he mentioned in a letter to Pococke (Pococke 432, trans from Holt).

Comparing the annotations in both volumes gives a picture of the orientalist at work. Pococke seems to have read, pencil in hand, with both volumes open, working word for word through the text, adding glosses in Laud 121 as he deciphered the Persian through the Arabic commentary.

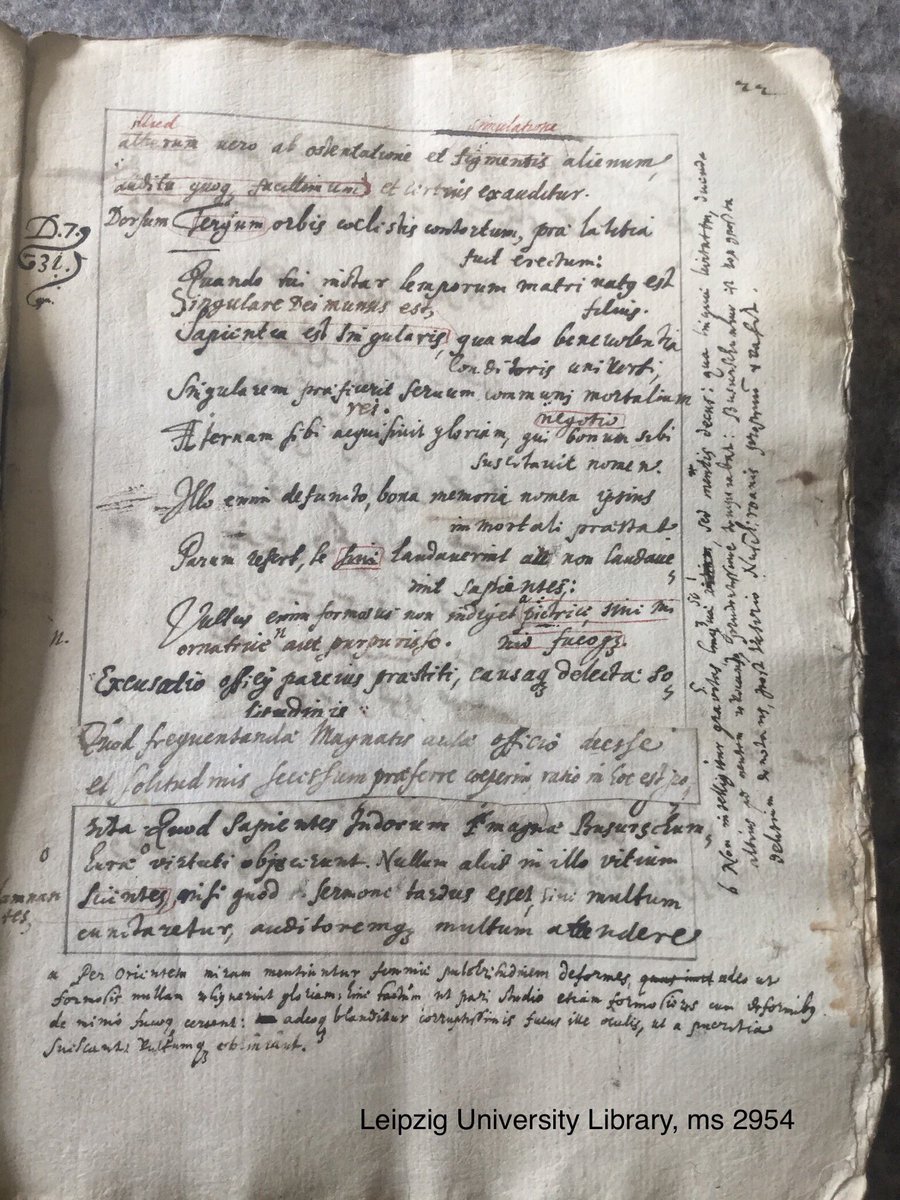

The commentary presents first (in red) the Persian original, then an Arabic translation of the corresponding text, then glosses on individual words. Through comparison of translation and original, and study of the commentary, Pococke produced his interlinear Latin glosses.

Pococke’s marginalia in the commentary show a different kind of annotating. Here, he extracted grammatical information, specifically, verb forms. As he read, Pococke tried to piece together the rules of Persian verb conjugation (not always correctly).

Pococke didn’t make it very far in his reading of the Gulistān—or, it seems, in learning Persian—but the Oxford mss are interesting as a glimpse into how a seventeenth-century orientalist might use a literary commentary to approach both a work of literature and a language...

and as an example of the functional differentiation of scholarly annotations between multiple manuscripts.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh