This is a story about how I lost $10,000,000 by doing something stupid.

Ten. Million. Dollars.

Literally up in smoke. Money bonfire.

That’s enough to retire with $250,000+ in annual income.

Here’s what happened…

Ten. Million. Dollars.

Literally up in smoke. Money bonfire.

That’s enough to retire with $250,000+ in annual income.

Here’s what happened…

In 2009, @metalab was a small but profitable agency.

The business was making a couple hundred thousand dollars a year in annual profit and I was trying to figure out how to invest the profits.

Agencies can be great businesses, but they are HARD.

The business was making a couple hundred thousand dollars a year in annual profit and I was trying to figure out how to invest the profits.

Agencies can be great businesses, but they are HARD.

You lose clients at random, your pipeline dries up on a dime. It’s feast or famine and unpredictable.

I kept reading about what @dhh and @jasonfried were doing with Basecamp, building software for themselves then selling monthly access to it.

wired.com/2008/02/mf-sig…

I kept reading about what @dhh and @jasonfried were doing with Basecamp, building software for themselves then selling monthly access to it.

wired.com/2008/02/mf-sig…

This was a relatively new concept back in those days, and it seemed like they were living the dream. I had a business crush.

The model they used for Basecamp was:

1. Build great software that scratched their own itch (project management)

2. Assume others have this problem

The model they used for Basecamp was:

1. Build great software that scratched their own itch (project management)

2. Assume others have this problem

3. Charge a monthly recurring amount to give them access (SaaS)

4. Focus on organic growth via product improvement and public writing

5. Spend less than they make

6. Profit

4. Focus on organic growth via product improvement and public writing

5. Spend less than they make

6. Profit

As a stressed out agency owner, this sounded INCREDIBLE.

Make money while you sleep for building cool software for yourself. Easy.

Make money while you sleep for building cool software for yourself. Easy.

I loved Jason and David’s focus on building a business on your own terms, in a way that made you happy.

I hated the idea of having some annoying VC involved, pressuring me to grow or move to San Francisco (believe it or not, that was almost 100% required at the time).

I hated the idea of having some annoying VC involved, pressuring me to grow or move to San Francisco (believe it or not, that was almost 100% required at the time).

I wanted to stay in control of my business and my life.

I had the money. So I decided to follow suit.

My biggest problem at the time was managing people. I was up to about 10 employees and I was having trouble keeping track of what everyone was working on.

I had the money. So I decided to follow suit.

My biggest problem at the time was managing people. I was up to about 10 employees and I was having trouble keeping track of what everyone was working on.

I was a huge to-do list junkie, but back then all of the task apps were either single-player or weird desktop apps with syncing issues.

I decided to build a shared to-do list app for teams.

I decided to build a shared to-do list app for teams.

I grabbed a couple of devs from the agency and we started working on it. About 9 months later we were in beta.

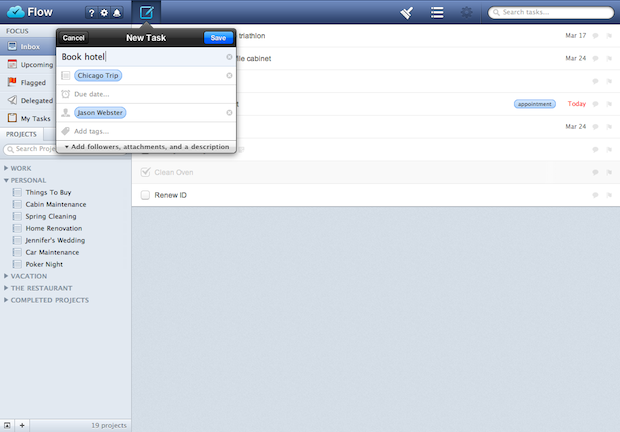

We called it Flow, and it was actually really cool.

From day one, it was a huge hit. A lot of people had the same problem and there was nothing else like it.

We called it Flow, and it was actually really cool.

From day one, it was a huge hit. A lot of people had the same problem and there was nothing else like it.

When we turned on billing for our beta users, we jumped to $20k MRR in the first month. We started growing at 10% per month and were the new hotness.

I got reach outs from all the top VCs and tons of tech luminaries started using the product.

We’d made it…or so I thought.

I got reach outs from all the top VCs and tons of tech luminaries started using the product.

We’d made it…or so I thought.

There was just one problem:

I was consistently spending 2-3x our monthly revenue and losing money.

And not venture capital. Out of my personal bank account.

I was consistently spending 2-3x our monthly revenue and losing money.

And not venture capital. Out of my personal bank account.

I kept reassuring my then-CFO @_Sparling_.

He was freaking out watching me burn so much money.

I thought he was shortsighted:

"We are going to make millions! Maybe billions!"

"You have to spend money to make money!"

"Once we launch this new feature, then everyone will see!"

He was freaking out watching me burn so much money.

I thought he was shortsighted:

"We are going to make millions! Maybe billions!"

"You have to spend money to make money!"

"Once we launch this new feature, then everyone will see!"

Then I heard a name start popping up. Quietly at first, then a lot.

Asana.

Asana.

It turned out that Dustin Moskovitz (@moskov), the billionaire co-founder of Facebook, was a fellow to-do list junkie, and he was quietly working on his own product.

A few months later it went live.

And I breathed a big sigh of relief.

A few months later it went live.

And I breathed a big sigh of relief.

It was ugly! It was designed by engineers. Complicated and hard to use.

Not a threat in the slightest.

I felt validated:

With a team a quarter of the size, and a fraction of the money, we had built what I felt was a superior product.

Not a threat in the slightest.

I felt validated:

With a team a quarter of the size, and a fraction of the money, we had built what I felt was a superior product.

Around this time, Dustin invited me for a coffee in San Francisco.

He implied—in the nicest possible terms—that they were going to crush us.

(Emphasis on nice, he is a very nice, humble dude. Both Dustin and @christianreber, my two key competitors, turned out to be mensches)

He implied—in the nicest possible terms—that they were going to crush us.

(Emphasis on nice, he is a very nice, humble dude. Both Dustin and @christianreber, my two key competitors, turned out to be mensches)

He walked me through who was backing them, how much cash they had, how they had hired top executives from huge companies, and that it was only a matter of time until they beat us on product and outspend us on marketing.

I laughed!

I was on the bootstrapping train. He was drinking Silicon Valley KoolAid.

“Nice try!” I told him “let the games begin” and we left with a friendly handshake.

I was on the bootstrapping train. He was drinking Silicon Valley KoolAid.

“Nice try!” I told him “let the games begin” and we left with a friendly handshake.

Flow kept growing quickly, but our customers were demanding.

They wanted an iPhone app.

They wanted an Android app.

They wanted an iPad app.

They wanted a Mac app.

They wanted an iPhone app.

They wanted an Android app.

They wanted an iPad app.

They wanted a Mac app.

Asana quickly released clients on all platforms.

After all, they had a dev team 5x the size.

Suddenly it was a key feature when people compared Asana and Flow side-by-side. Mobile was table stakes.

We had to keep up.

After all, they had a dev team 5x the size.

Suddenly it was a key feature when people compared Asana and Flow side-by-side. Mobile was table stakes.

We had to keep up.

Almost overnight, our burn doubled.

I continued to pound cash into the business. $20k, $40k, $60k, $80k, $150k a month.

For designers, more developers, more marketers, more office space.

More everything.

I continued to pound cash into the business. $20k, $40k, $60k, $80k, $150k a month.

For designers, more developers, more marketers, more office space.

More everything.

Until my bank balance couldn't keep up.

We started almost missing payroll and rent.

At one point in 2012 Chris even had to inject cash from his personal account so we wouldn’t miss payroll.

It was terrifying.

We started almost missing payroll and rent.

At one point in 2012 Chris even had to inject cash from his personal account so we wouldn’t miss payroll.

It was terrifying.

I started to realize how big a bet this was.

I had no other investments outside of MetaLab, which was struggling at the time.

At this point, I had invested millions of dollars, without even realizing it.

Just continual weekly injections over the course of years.

I had no other investments outside of MetaLab, which was struggling at the time.

At this point, I had invested millions of dollars, without even realizing it.

Just continual weekly injections over the course of years.

Death by a thousand paper cuts.

Then, Asana raised $28 million and started pouring it into marketing.

We didn’t do paid marketing, it seemed douchey and aggressive.

We focused on organic growth....

Then, Asana raised $28 million and started pouring it into marketing.

We didn’t do paid marketing, it seemed douchey and aggressive.

We focused on organic growth....

Until that point, we had just just done Field of Dreams marketing:

“If you build it, they will come”

But I wasn't Jason Fried. In my opinion, one of the best marketers of our generation.

My blog posts barely made a dent. I didn't understand marketing.

“If you build it, they will come”

But I wasn't Jason Fried. In my opinion, one of the best marketers of our generation.

My blog posts barely made a dent. I didn't understand marketing.

We were a fart in the wind.

Suddenly, Asana ads were everywhere.

Billboards. Bus stops. Conferences. Airports. Google. Facebook. Capterra.

Suddenly, Asana ads were everywhere.

Billboards. Bus stops. Conferences. Airports. Google. Facebook. Capterra.

Even OUR OWN Google keywords were plastered with “Asana vs. Flow” paid links.

We started burning money on ads and hiring sales people just to keep a toe hold, but mostly we focused on making the product better than theirs.

Our one remaining advantage.

We started burning money on ads and hiring sales people just to keep a toe hold, but mostly we focused on making the product better than theirs.

Our one remaining advantage.

But our product was suffering…

In order to stay competitive, we had underinvested in our engineering team due to cash constraints and stretched them across mobile, desktop, and web.

We started to get an endless stream of bug reports from our customers.

In order to stay competitive, we had underinvested in our engineering team due to cash constraints and stretched them across mobile, desktop, and web.

We started to get an endless stream of bug reports from our customers.

Our growth started slowing.

20% monthly growth dropped to 5%.

Customers weren’t getting the features they wanted.

Our clients were unreliable and had syncing issues.

Our team felt frustrated and under resourced and we churned through staff.

20% monthly growth dropped to 5%.

Customers weren’t getting the features they wanted.

Our clients were unreliable and had syncing issues.

Our team felt frustrated and under resourced and we churned through staff.

We had to hit pause and spend years—literally years—rewriting all of our clients, only to emerge on the other side to see….

Asana had hired designers.

At first, a tiny little team. Nothing to worry about.

But after a year or two, they started hiring a huge team of incredible people.

One day I woke up to see that Asana had fully relaunched. Their marketing site looked…great.

Better than ours...

At first, a tiny little team. Nothing to worry about.

But after a year or two, they started hiring a huge team of incredible people.

One day I woke up to see that Asana had fully relaunched. Their marketing site looked…great.

Better than ours...

Their new app, while not perfect, had all the features we wished we had time to make, worked on more platforms and most importantly was fast and not buggy.

By this point, we were burning over $150,000 per month.

By this point, we were burning over $150,000 per month.

Chris was tearing his hair out and pointed out that we had burnt through something like $5MM with no end in sight.

Still, we powered on for YEARS. We even doubled down and raised money—too little too late—from some friends of mine.

Still, we powered on for YEARS. We even doubled down and raised money—too little too late—from some friends of mine.

We decided that we didn’t need to “own that market”.

We could just have a small slice of pie. We focused on base hits.

We could just have a small slice of pie. We focused on base hits.

For a while, that looked like an OK strategy.

Our revenue growth slowed, we kept on growing.

Until one day it didn’t.

Our revenue growth slowed, we kept on growing.

Until one day it didn’t.

Churn caught up with us, customer acquisition cost became unprofitable (Asana and others could afford to spend way more due to higher customer lifetime value), bugs continued to dominate our time, and Asana and others kept making their product better.

One day recently, I looked at Asana and it slapped me in the face:

It’s better.

Their marketing is better.

Their product is better.

Their features are better.

Their enterprise support is better.

Their integrations are better.

They won. We lost.

It’s better.

Their marketing is better.

Their product is better.

Their features are better.

Their enterprise support is better.

Their integrations are better.

They won. We lost.

12 years and over $10MM+ lit on fire, we are are done burning money in a losing battle. We give up.

The writing is on the wall. Dustin was right.

We lost the war, due to inexperience, product myopia, and a lack of capital in a highly capital intensive and competitive space.

The writing is on the wall. Dustin was right.

We lost the war, due to inexperience, product myopia, and a lack of capital in a highly capital intensive and competitive space.

Today, Flow is a shadow of its former self.

We’ve were forced to downsize it to breakeven and shifted to a team based in India led by my friend @mohitmamoria to keep our remaining customers happy.

We’ve were forced to downsize it to breakeven and shifted to a team based in India led by my friend @mohitmamoria to keep our remaining customers happy.

It’s a business that has to spend less than it makes and focus on making its customers happy.

We aren't fighting Asana anymore.

This is a very expensive slice of humble pie.

And we are holding our noses and wolfing it down.

We aren't fighting Asana anymore.

This is a very expensive slice of humble pie.

And we are holding our noses and wolfing it down.

At its peak, Flow did about $3MM of ARR.

Today it’s sitting at about $900k ARR, breakeven, with a low growth rate.

Today it’s sitting at about $900k ARR, breakeven, with a low growth rate.

Sure, it could turn into something, but I will never make my investment back and barring a miracle, it will never own a large chunk of the productivity market.

In retrospect, we were like Fiji waging war on the United States with a collection of AK-47s and speed boats vs. artillery and aircraft carriers.

We got obliterated. Obviously.

Looking back as a more mature entrepreneur, this was inevitable...

We got obliterated. Obviously.

Looking back as a more mature entrepreneur, this was inevitable...

VCs, friends—heck, my own business partner—all walked me through all of this, but it took years to sink in.

It was a slow 12 year train wreck.

A thousand paper cuts, driven by my complete inexperience and incompetence on my part.

It was a slow 12 year train wreck.

A thousand paper cuts, driven by my complete inexperience and incompetence on my part.

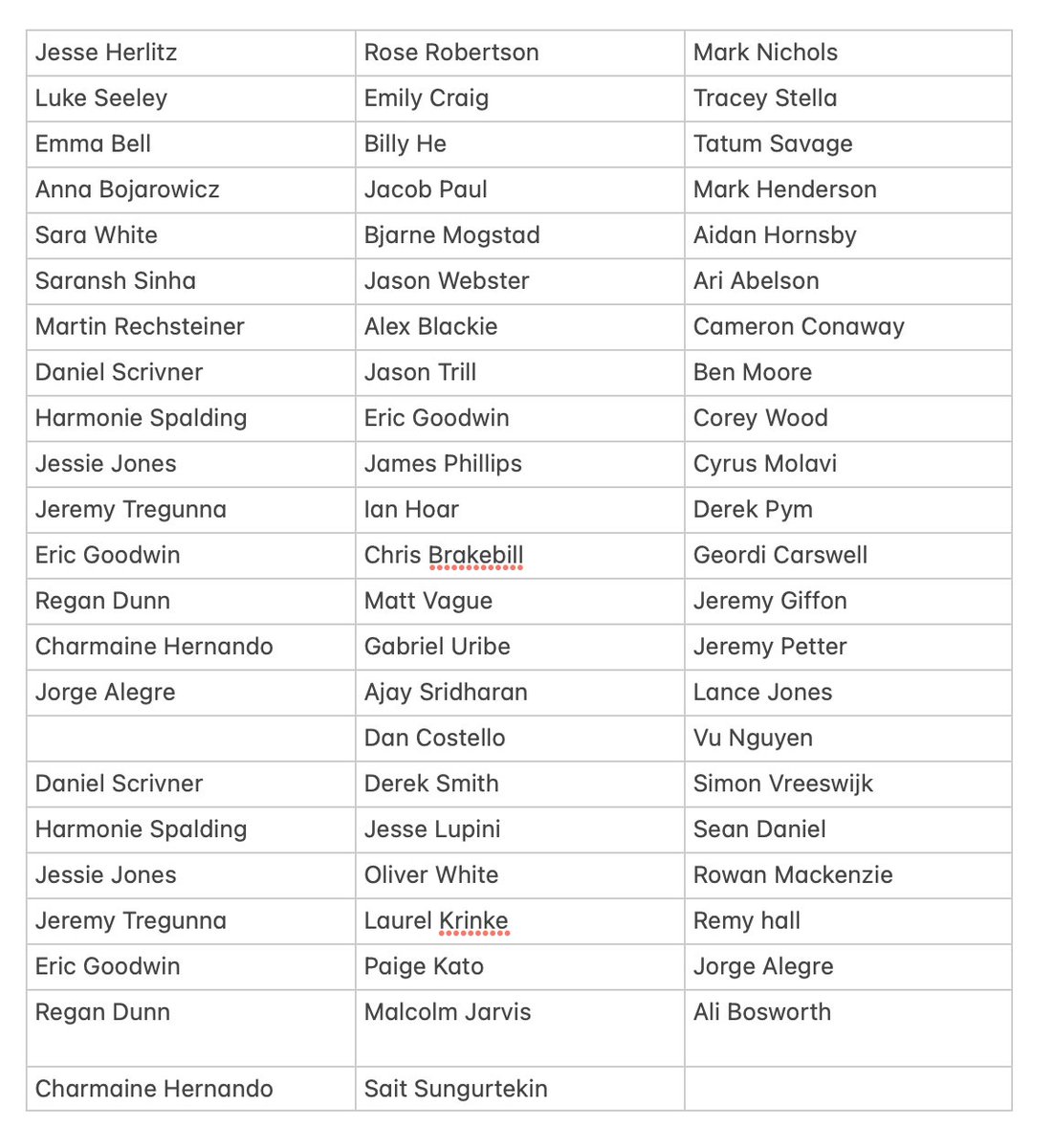

The absolute worst part about this is that a team of incredibly smart people, many of whom have become good friends, worked on a company—some of them for a decade or more—that didn’t turn out.

A huge thank you to all of the people who worked on Flow over the past decade, I owe you all, big time.

I'm so sorry it didn't work out the way we had hoped and the responsibility falls squarely on my shoulders:

I'm so sorry it didn't work out the way we had hoped and the responsibility falls squarely on my shoulders:

I think that failure is the best teacher.

But better than failing is getting to learn by reading about my failures in a tweet instead of losing $10MM yourself.

But better than failing is getting to learn by reading about my failures in a tweet instead of losing $10MM yourself.

In this instance, I learned a lot.

The key takeaways are:

1. If you are in a competitive VC-funded space, it’s foolish to compete without raising money. Don't bring a knife to a gun fight.

The key takeaways are:

1. If you are in a competitive VC-funded space, it’s foolish to compete without raising money. Don't bring a knife to a gun fight.

2. The best product doesn’t always win, and product is not a longterm competitive advantage.

3. If a tree falls in the forest and nobody is around to hear it, it didn’t fall.

3. If a tree falls in the forest and nobody is around to hear it, it didn’t fall.

4. Every developer in the world wakes up thinking “I should build a to-do list app” and people love jumping between productivity apps and workflows. There is no moat in productivity—avoid it if you can.

5. Running a SaaS business without deeply understanding churn, LTV, CAC etc, is like flying a plane without instrumentation—really stupid and dangerous.

6. Failure sneaks up on you slowly, then all at once.

7. R&D is EXPENSIVE. Especially when competing with venture.

6. Failure sneaks up on you slowly, then all at once.

7. R&D is EXPENSIVE. Especially when competing with venture.

8. If you’re competing on features, it never stops and is an ever-increasing line item.

9. Good product with great marketing beats amazing product with no marketing.

9. Good product with great marketing beats amazing product with no marketing.

10. Bootstrapping works best in uncompetitive spaces/niches or if you have an unfair advantage (a personal brand, unique customer acquisition channel, etc).

The best way to learn is to walk around sticking forks in electrical sockets and adjusting accordingly.

This one hurt. A lot.

I'll try to keep sharing my screw ups as they happen.

Follow me at @awilkinson.

This one hurt. A lot.

I'll try to keep sharing my screw ups as they happen.

Follow me at @awilkinson.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh