Gandharan Masterpieces from Peshawar & Lahore

(New edits on photos taken just before lockdown last year.)

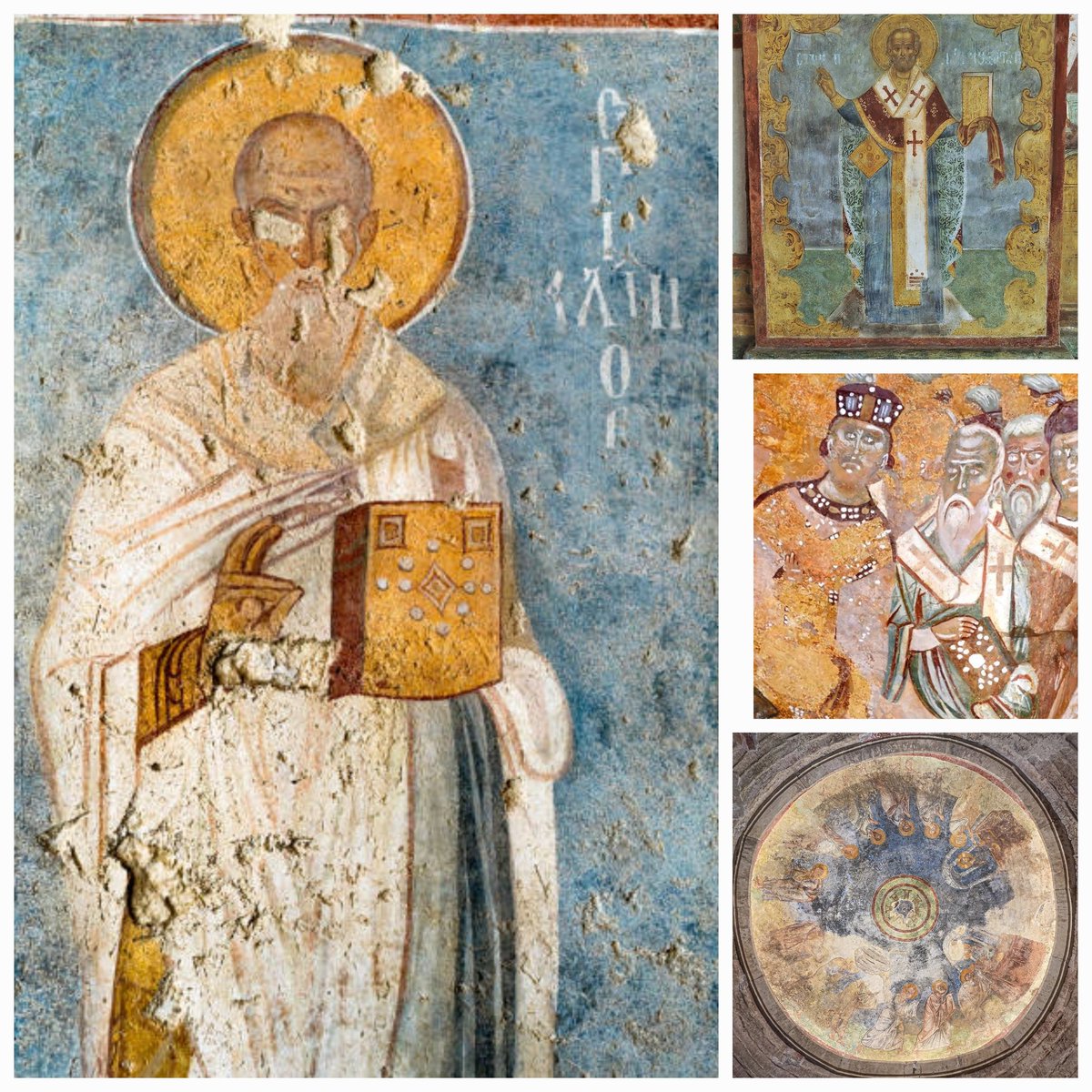

How I love these spectacular black-schist figures, standing eternally meditating, preaching or fasting.

(New edits on photos taken just before lockdown last year.)

How I love these spectacular black-schist figures, standing eternally meditating, preaching or fasting.

The physique is magnificent: muscles ripple beneath the diaphanous folds of the Buddha’s lunghi or toga...

The saviour sits with half-closed eyes and legs folded in a position of languid relaxation. His hair is oiled and groomed into a beehive topknot; his high, unfurrowed forehead is punctuated with a round urna mark.

At the same time as the artists of Gandhara were developing their image of the Buddha with the help of Greek and Roman models, the artists of Mathura were developing a slightly different more Indic Buddha based on the burly images of yakshas.

(Both from the Mathura Museum)

(Both from the Mathura Museum)

Art historians still debate which came first, the Mathura or Gandharan Buddha. But the two schools drew closer together, especially in their depiction of drapery, and by the Gupta period in the 5th/6thC the superb Mathura & Sarnath Buddhas gave a more Indic feel to Gandaran forms

All these images will be on display in an exhibition on the Art of Ancient India @ArtVadehra in Delhi in May and @grosvenorart in London in July

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh