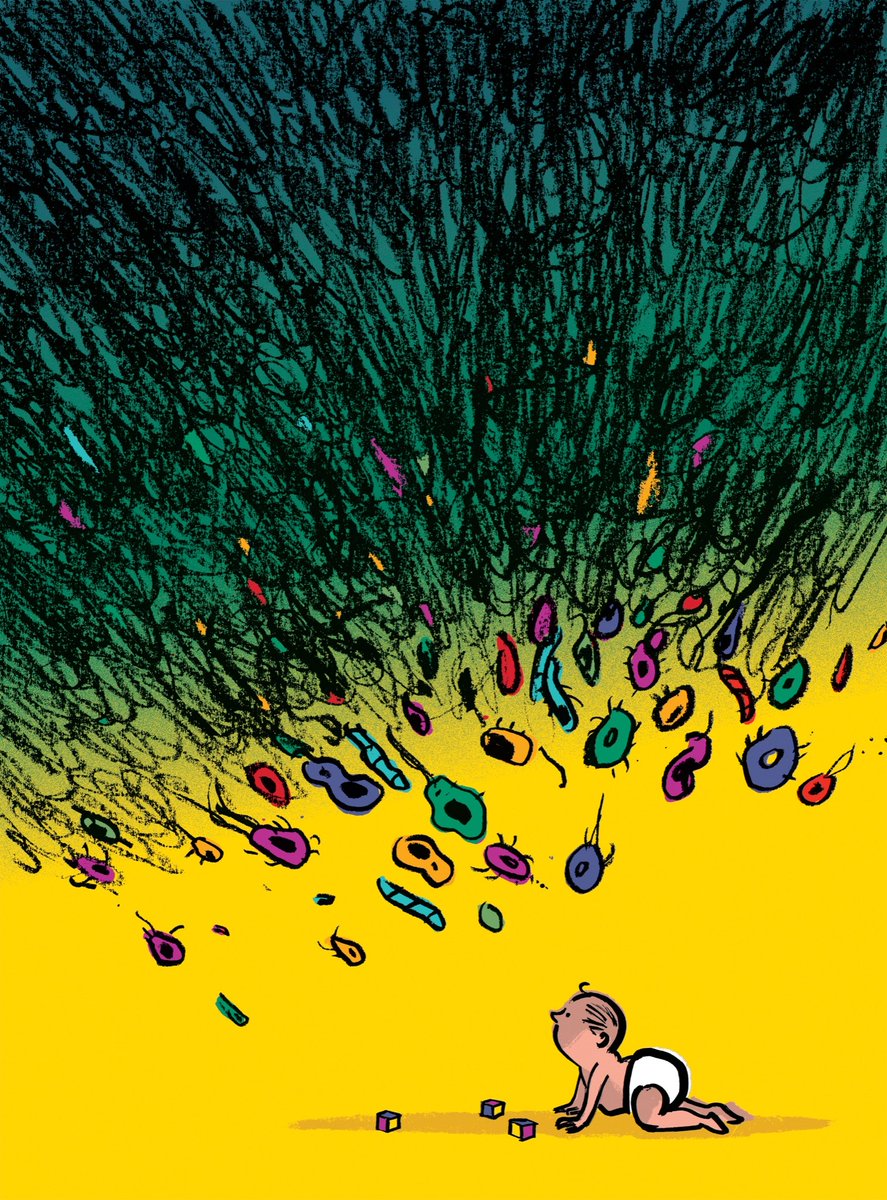

Like a city, inside of the cell is organised by highways and roads (microtubules, actin), motors (dynein, kinesins, myosins) cargoes (e.g. receptors in endosomes, viruses) post-offices sorting cargoes (sorting endosomes), garbage clean-up (autophagosomes, lysosomes) and much more

Every piece of the puzzle listed above is a field on its own! We now know about the exquisite dynamics of microtubules, or how motors move. We know about the process of endocytosis at the plasma membrane and proteins that define distinct endosomal populations (Rabs)

At the level of single cells, how individual processes building up the endosomal network integrate to evince trafficking and signalling outcomes is an exciting field. Individual processes building up the endosomal network are inherently stochastic, making measurements non-trivial

How can we study such processes? Advent of light-sheet based approaches allow imaging of the whole cell volumes with high-temporal resolution. When acquired at high-temporal resolution for long time durations, fast stochastic processes that build up this system can be captured

With whole-cell volumes captured, one can extract quantitative parameters for ALL events, something that was not possible earlier because events would be missed owing to poor time resolution or lack of photo gentleness, that is required for long measurements for sufficient events

Two examples of such an approach applied to endosomes are: measuring the kinetics of phosphoinositide conversion in endosomal populations (He et al. , 2017) and ligand induced whole cell level perturbation and engagement of an early endosomal adaptor (York et al., 2021)

Open questions include mechanisms of endosomal maturations, how the timing of the 'conveyor belt' of endosomes are maintained at a population level. Phosphatases and kinases are at the centre of this (see below and compare the reconstituted system from the Groves lab to this)

Experimental approaches in this field need mathematical biology too. Here are two examples of awesome papers that discuss endosomal maturations and sorting of cargoes. Large numbers of events at whole-cell levels can now be measured to provide experimentally measured parameters.

Phosphoinositide conversions, by various phosphatases and kinases are at the centre of endosomal conversions. Reconstitution approaches are a powerful way to understanding the mechanisms, for e.g. this stochastic geometry sensing in a kinase-phosphatase competitive reaction

Lastly, understanding the endosomal system beyond proteins that 'regulate' a process in this system is perhaps within reach by developments in imaging, not to mention the importance of every aspect of endosomal trafficking relatable to many diseases, including viral infections.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh