1/ The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan (Sebastian Mallaby)

"He was a conservative who could advocate tax hikes, a libertarian who repeatedly supported bailouts, an economist who often behaved more like a Washington tactician." (p. 6)

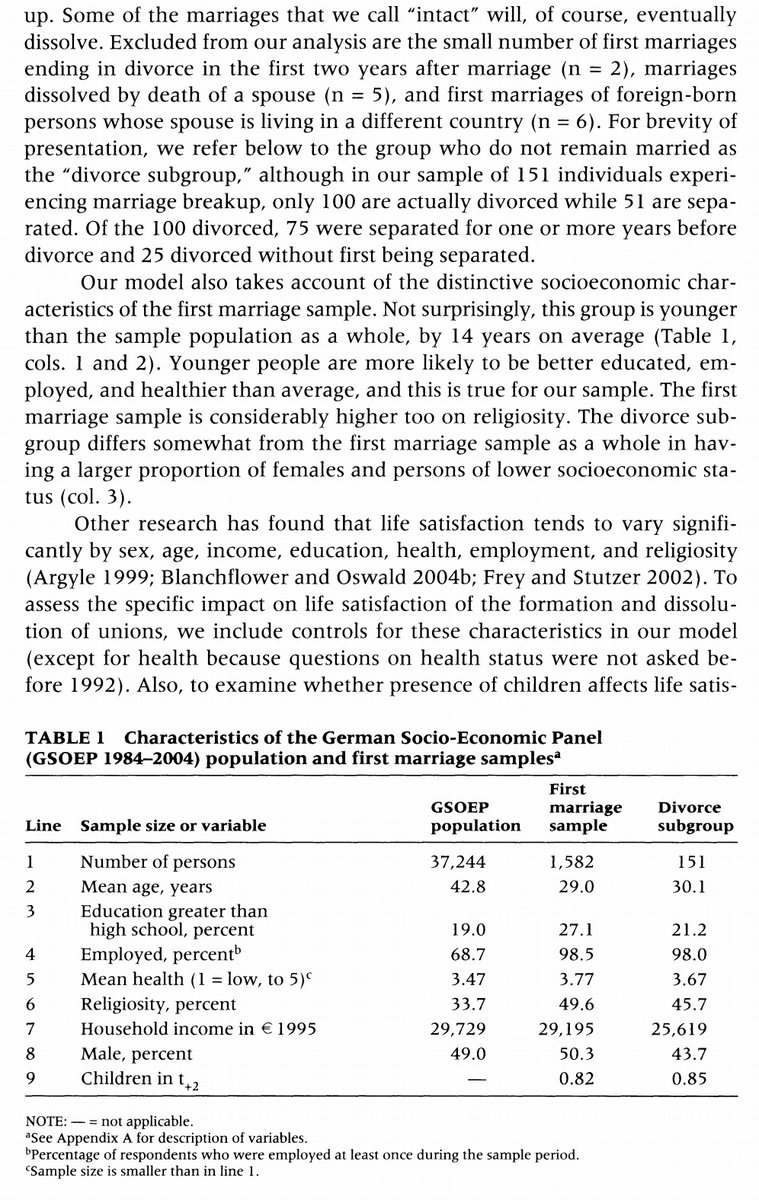

amazon.com/Man-Who-Knew-T…

"He was a conservative who could advocate tax hikes, a libertarian who repeatedly supported bailouts, an economist who often behaved more like a Washington tactician." (p. 6)

amazon.com/Man-Who-Knew-T…

2/ "Much of the post-crisis commentary has reduced Greenspan to a caricature. He is accused of believing blindly in models. He was, in fact, a leading skeptic of them. He is blamed for underestimating the propensity of financial systems to run wild.

3/ "He had, in fact, spent fifty years warning of treacherous credit cycles.

"A man who embraces the gold standard and then presides over the financial printing press is surely no simple ideologue." (p. 6)

"A man who embraces the gold standard and then presides over the financial printing press is surely no simple ideologue." (p. 6)

4/ "The inflation of the late 1960s had destroyed the comforting system of fixed exchange rates and regulated caps on bank interest rates; meanwhile, technological change and globalization made it impossible to resist the explosion of trading in derivatives.

5/ "To cite just one telling illustration, between 1970 and 1990 the cost of the computer hardware needed to price a mortgage-backed security plummeted by more than 99%. No wonder securitization took off during this period.

6/ "So when Greenspan and his allies judged that certain regulations were obsolete, they were not the deluded victims of some libertarian fever. Rather, they were grappling with how best to manage the old system’s inevitable demise.

7/ "The evident risks in the new financial methods had to be balanced against real benefits. Currency derivatives offered exporters and importers a way to cancel out each other’s risks—far from rendering the world unstable, financial engineering promised to make it safer.

8/ "Contrary to caricature, Greenspan and his allies did not expect private actors to avoid manias and crashes, but they believe that supervisors would do no better at averting them. They were not naïve efficient-market believers. They were government-can’t-do-better realists.

9/ "His allies came from both sides of the divide. Carter, a Democrat, got rid of the last vestiges of interest-rate regulation for banks. Clinton signed the reform of 1999 that ratified the breakdown of the Depression-era separation between banks, insurers, & securities houses.

10/ "One of the virtues of biography is that it allows readers to understand decision making as it really is—imperfect, improvised, contingent upon incomplete information and flawed human nature.

11/ "Future generations will be asked to eliminate financial risks, but such risks are inescapable. The delusion that statesmen can perform the impossible—(the “maestro”)—breeds complacency among citizens and hubris among leaders." (p. 9)

More on this:

https://twitter.com/ReformedTrader/status/1365779414873608195

12/ "At university, Greenspan encountered a climate dominated by legions of returning servicemen lounging around the ornate fountain in Washington Square Park. They were as sympathetic to government as any student cohort has ever been—government was paying for their education.

13/ "Although New Deal progressivism dominated the country, Greenspan refused to be formed by it. He came of age in the era of Keynesian thinking, but he emerged as an un-Keynesian." (p. 27)

14/ "The twin engines of his childhood—an introspective isolation on the one hand, a burning ambition on the other—were driving Greenspan to educate himself, with little influence from outsiders." (p. 30)

15/ "To counter what Hansen called secular stagnation, the government would have to discourage excess saving by redistributing from the high-saving rich to the high-spending poor. It would have to boost spending and tolerate large budget deficits. But Greenspan was not convinced.

16/ "The contention that excess savings would pile up, with nobody willing to spend or invest, seemed pessimistic. To a man whose imagination had been captured by the railway magnates of the 19th century, it seemed that there would always be new technologies to bet on." (p. 32)

17/ "Just measuring the economy was challenge enough: data series had to be cyclically adjusted, seasonally adjusted, and checked for consistency against other series—all without the assistance of computers. There was more value in this humble task than in fancy mathematics.

18/ "Even the cleverest econometric calculation was limited because yesterday’s statistical relationships might break down tomorrow.

"Greenspan never shed his conviction that the quality of an economist’s data mattered more than the sophistication of his modeling." (p. 38)

"Greenspan never shed his conviction that the quality of an economist’s data mattered more than the sophistication of his modeling." (p. 38)

19/ "The prospect of a conflict forced the United States to redouble military spending. Truman was anxious to have the Fed control its borrowing costs. The president telephoned the Fed chairman at home and insisted that rates on long-term bonds must not breach the 2.5% ceiling.

20/ "Upon fears of wartime rationing, consumers rushed to load up on everything from cars to washing machines, triggering inflation. In Nov 1950, the consumer price index rose at an annual rate of 20%, and in the two months following China’s invasion, it advanced even faster.

21/ "The threat of radically unstable prices shocked the Fed’s leaders into doing what Burns and his contemporaries never imagined they would do. They resolved to control prices by forcing interest rates up, no matter how much Truman might invoke cold-war imperatives." (p. 40)

22/ "Greenspan wanted fame and fortune, but his personality was ill suited to climbing steep corporate ladders; he had no appetite for turf battles, no stomach for confrontation. As a business consultant he could succeed in his shy way, through sheer mastery of numbers." (p. 44)

23/ "Through the 1940s, Friedman had accepted Burns’s view of inflation as the product of excess government spending. But by the late 1950s, he was approaching the point when he would declare that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”

24/ "As the financial system expanded, and with it the volume of borrowing and lending, the price of capital was coming to be recognized as *the* central price in a capitalist system." (p. 47)

25/ "By enabling people to construct portfolios that suited them, sophistication reduced the price at which citizens would commit savings: a lower cost of capital and greater prosperity for all. Greenspan never shed this optimism, even when events challenged him to do so." (p.49)

26/ "Just as the construction entrepreneur will erect an office block for $10 million if it can be sold for $15 million, so a manufacturing entrepreneur will build a new industrial enterprise for $100 million if he can expect to sell shares in it for $150 million.

27/ "In the upswing (downswing), high (low) share prices spur business investment, triggering boom (slowdown).

"If central bankers aspired to smooth out the peaks and troughs in the business cycle, they would have to control asset bubbles, Greenspan observed." (p. 50)

"If central bankers aspired to smooth out the peaks and troughs in the business cycle, they would have to control asset bubbles, Greenspan observed." (p. 50)

28/ "As he watched traders on the Comex floor, Greenspan learned that prices reflected economic fundamentals only imperfectly. They were driven in the short term by screams and hand signals. The operators in this environment frequently knew nothing about the metals they traded.

29/ "You had to read body language: which side had more capital; which side had the balls to bet the biggest? Greed, fear, and ego trumped inventories.

"Because the future is uncertain, investors who bid risk premiums down to nothing have taken leave of their senses." (p. 57)

"Because the future is uncertain, investors who bid risk premiums down to nothing have taken leave of their senses." (p. 57)

30/ "Greenspan was unusual in promoting women to positions of responsibility.

"He judged employees according to their abilities; and he could spot a bargain, too—because of widespread discrimination, talented women could be hired cheaply." (p. 84)

"He judged employees according to their abilities; and he could spot a bargain, too—because of widespread discrimination, talented women could be hired cheaply." (p. 84)

31/ "The Kennedy team’s faith in economic modeling struck Greenspan as folly. Mobil Oil had asked for a general forecast of the economy; in the course of delivering what his client wanted, Greenspan concluded that such macroeconomic projections were more art than science.

32/ "If state-of-the-art modeling could not pinpoint when the economy was headed for a slump, it followed that policy makers could not be expected to know when to order up a stimulus—fine-tuning seemed more likely to misfire than to hit its target." (p. 86)

33/ "Nixon was not about to embrace Greenspan’s libertarian principles wholeheartedly. He balanced conservative advisers such as Buchanan and Anderson with liberals like Price; the country had moved to the left, and he wouldn't win on a platform to restore the nineteenth century.

34/ "The Depression had increased Americans’ appetite for government; yet the booming 1950s and 1960s had also further increased their appetite for government. Nixon could attack the Great Society at the margins, but a full-frontal assault would be electoral madness." (p. 110)

35/ 1/20/1969: "Nixon saluted America’s extraordinary prosperity—“No people has ever been so close to the achievement of a just and abundant society”—and affirmed his faith in fine-tuning, promising that America had “learned at last to manage a modern economy to assure growth.”

36/ "America’s output expanded for the ninety-sixth consecutive month; unemployment was at just 3.3%.

"But for the first time in Greenspan’s adult life, companies and households had substantial borrowings: the total stock of private debt, 52% of GDP in 1945, had doubled to 107%.

"But for the first time in Greenspan’s adult life, companies and households had substantial borrowings: the total stock of private debt, 52% of GDP in 1945, had doubled to 107%.

37/ "As rates rose, rising payments on the huge debt stock would hit Americans from one side (lower revenues from tight budgets) and slow growth from the other.

"Hedge funds lost their shirts—go-go was gone; the 1960s were over." (p. 129)

More on this:

"Hedge funds lost their shirts—go-go was gone; the 1960s were over." (p. 129)

https://twitter.com/ReformedTrader/status/1354855031665692674

38/ "As rates rose, S&Ls needed to compete with higher-yielding bonds in order to attract deposits. But they were prohibited from paying depositors more—like banks, which faced Regulation Q caps on the amount of interest they could pay, S&Ls were hamstrung by the government.

39/ "They could not recoup their money until their long-term mortgages matured. But the depositors who funded those mortgages were heading for the exits.

"The New Frontier quest for full employment had caused inflation to rise, which had caused market interest rates to rise.

"The New Frontier quest for full employment had caused inflation to rise, which had caused market interest rates to rise.

40/ "So S&Ls had to pay depositors more or face a catastrophic loss of funding. But interest-rate caps prevented the S&Ls from adjusting.

"The government had first confronted the industry with the challenge of inflation, then prevented the industry from adapting to it." (p. 129)

"The government had first confronted the industry with the challenge of inflation, then prevented the industry from adapting to it." (p. 129)

41/ "By Sept 1969, inflation rose to an annual rate of 5.7%, and the jobless rate jumped to 4%, up from 3.3% in Jan.

"A New Frontier–style regulatory clampdown on wages and prices would merely smother the symptoms; the underlying causes of price pressure had to be dealt with.

"A New Frontier–style regulatory clampdown on wages and prices would merely smother the symptoms; the underlying causes of price pressure had to be dealt with.

42/ "True to the blithe rhetoric of his inaugural speech, the president wanted an economy that generated jobs—never mind the inflationary consequences. Far from siding with economists on the need for monetary discipline, Nixon plotted ways to force the Fed into a looser policy.

43/ "The CEA economists did their best to push back.

"Indeed, if inflation originated partly in excess regulation, as the brainstorming session had concluded, Nixon’s plan to regulate wages and prices would only make things worse." (p. 135)

"Indeed, if inflation originated partly in excess regulation, as the brainstorming session had concluded, Nixon’s plan to regulate wages and prices would only make things worse." (p. 135)

44/ June 1970: "The Penn Central Transportation Company conglomerate was emblematic of the leveraging of the economy. It had borrowed wildly to go on an acquisition spree; then, when the combination of rising rates and a slowing economy hit, its debts proved unsustainable.

45/ "Fearful that this might trigger the collapse of dozens of leveraged conglomerates, the Fed kept its discount window open. To help banks attract funds and channel them to wobbly industrial concerns, it suspended the Regulation Q interest-rate cap on very large deposits.

46/ "Inflation, and the Fed’s response of higher rates, had created a fragility that only looser regulation could assuage. Contrary to the version of history that was accepted later, deregulation was at least partly a response to instability. It was not simply the cause." (p.135)

47/ "New Frontier economists had embraced the goal of “full employment.” To preserve the fixed exchange rate, the U.S. had to avoid inflation, which would undermine the value of its money. But to attain full employment, the U.S. had to do the opposite.

48/ "The dollar-gold link was close to breaking.

"The president resolved that the U.S. would leave the gold standard.

"Determined to fight inflation without enduring tighter budgets or higher rates, the president imposed wage and price controls." (p. 146)

"The president resolved that the U.S. would leave the gold standard.

"Determined to fight inflation without enduring tighter budgets or higher rates, the president imposed wage and price controls." (p. 146)

49/ "The commission called for the phasing out of Regulation Q, reflecting the almost universal agreement among experts that banks and S&Ls must be allowed to cope with inflation by adjusting the interest they paid to attract deposits.

50/ "It also aimed to shatter the silos dividing different types of lenders. S&Ls would henceforth be allowed to diversify out of mortgage lending and compete with banks, while banks would be allowed to underwrite municipal bonds and to sell mutual funds and insurance.

51/ "In the 1970s, economists from both sides of the political divide supported the deregulatory prescriptions: a balkanized financial industry served customers poorly; by fostering competition, the commission aimed to cut costs that penalized savers and borrowers.

52/ "Narrowly focused lenders threatened certain types of borrowers with episodes of credit drought. When rising interest rates caused deposits to lurch out of S&Ls, home buyers could not get mortgages elsewhere. Housing demand collapsed.

53/ "The cyclical building industry became even more volatile. Likewise, when savers withdrew money from regional banks, small businesses could no longer get loans.

"Wealthy Americans could find their way around regulatory constraints, whereas ordinary citizens were helpless.

"Wealthy Americans could find their way around regulatory constraints, whereas ordinary citizens were helpless.

54/ "If the government kept the regulatory screws on banks and S&Ls, capital would migrate to money-market funds; if interest-rate caps were extended to those funds, capital would migrate to Europe.

"Nearly all the commissioners accepted financial deregulation as inevitable.

"Nearly all the commissioners accepted financial deregulation as inevitable.

55/ "Change 1970s was shaped not by the deliberate planning of an expert commission but by market pressures and crises. The fact that Greenspan and his fellow commissioners proposed to phase out Regulation Q did not matter in the end; Regulation Q was neutered anyway.

56/ "The evolution of finance could have huge consequences, to be sure, but efforts to shape it were liable to founder. Technological changes, the exigencies of crises, and money’s mulish tendency to find its way around the rules—these forces decided things." (p. 151)

57/ "Price controls achieved the opposite of what was intended: by destroying companies’ incentives to invest, they led to shortages of basic goods, forcing prices upward. By screwing the lid on inflation temporarily, Nixon had set himself up for more inflation later." (p. 153)

58/ "Greenspan’s sense of separation between his advice and the president’s decisions came naturally to him. It was part of his loner psychology: he had relatively little need for others' approval, so he did not take offense if his advice was disregarded.

59/ "As a consultant, he had spent two decades providing clients with analysis and feeling blissfully indifferent as to what they did with it. His sense of separation was also convenient. It allowed him to remain intellectually honest but still emerge as a popular team player.

60/ "Senior officials from the president on down trusted his analysis because it seemed not to come burdened with any policy agenda. Precisely because he appeared not to want influence, Greenspan accumulated plenty of it." (p. 166)

61/ "Greenspan had a way of expounding on data: he made it clear that everything was unclear, so that laymen could not possibly grasp what was going on. Then, having confused his audience into submission, he offered a rescuing hand in the form of his own forecast." (p. 169)

62/ "Greenspan was capable of tempering his views in order to be at the center, as his advice on Ford’s tax rebate demonstrated. But in his ideal world, he would be both a libertarian and a power player. Margaret Thatcher allowed him to dream this might be possible." (p. 179)

63/ "Having borrowed too much, spent too much, and kowtowed to the unrealistic demands of its people, New York’s municipal government had reached the brink of bankruptcy in May 1975 and come cap in hand to Washington. Most of the rest of the country seemed disinclined to help.

64/ "New York had indulged its municipal employees shockingly: “You can’t retire people after twenty years, at the age of thirty-eight or thirty-nine, at half their highest salary,” one congressman complained." (p. 195)

More on this:

https://twitter.com/ReformedTrader/status/1111357546848120832

65/ "At Greenspan’s prompting, President Ford rebuffed New York’s plea for a bailout.

"If America continued to slither down this slope, each bailout would furnish justification for the next, and pretty soon the government would backstop every debt in the nation." (p. 196)

"If America continued to slither down this slope, each bailout would furnish justification for the next, and pretty soon the government would backstop every debt in the nation." (p. 196)

66/ "But a Fed study showed that 179 banks held state and city securities worth more than half their capital, so a sharp fall in their value would compel cuts in lending. Institutions legally required to dump NY securities once the city defaulted could generate contagion.

67/ "New York made strides toward addressing its problems. It embraced spending cuts, imposed a $200 million tax hike, reduced interest payments to bondholders, cut retirement benefits for municipal workers, and arranged to borrow $2.5 billion from the city’s pension fund.

68/ "Even so, Ford’s call for a bailout constituted a climbdown. Greenspan had argued that New York could fix its problems by itself. Now Ford insisted that Washington should help, even though there was no way to be sure that New York would implement all the promised reforms.

69/ "NYC needed a second package of federal loan guarantees in 1978. The city drew on federal support for more than a decade.

"Just as each bailout strengthened the case for the next one, Ford’s denial of assistance caused NYC to make itself more deserving of assistance.

"Just as each bailout strengthened the case for the next one, Ford’s denial of assistance caused NYC to make itself more deserving of assistance.

70/ "Americans have almost never been able to resist bailouts. Even when the intellectual tide turned in favor of conservatives, Americans continued to look to the government for rescues whenever crises struck. Later, Greenspan himself would join the bandwagon." (p. 200)

71/ "By the time of Ford’s electoral defeat, the inflationary pressures were building dangerously—the CPI toped 14% in 1980. Whoever presided over economic policy in the late 1970s was therefore doomed to suffer huge reputational damage." (p. 207)

72/ "If a home increased by $100,000 and the homeowner took out a second mortgage for 80% of that increase, the extra spending power did not show up in national accounts. The impact of asset prices occurred under the radar. Greenspan worked on quantifying the home-price effect.

73/ 1977: "If the housing boom came to an end, the economy would slow. There was a “danger that the rise in home prices could take on a speculative hue,” Greenspan observed. “The assumption of ever rising prices for new homes is not valid.” " (p. 209)

74/ "Greenspan forced listeners to consider multiple scenarios rather than binary 'yes/no' decisions. If the dollar rose, two consequences might develop. If inflation ticked up, there were four possible versions of the future." (p. 211)

He was a 'fox':

He was a 'fox':

https://twitter.com/ReformedTrader/status/1326234446668812288

75/ "Unlike Friedman and the monetarists, Greenspan never put stock in stripped-down models that forecast the future path of the economy by tracking a favored measure of the money supply; he was far too interested in the specific workings of industry and government budgets.

76/ "Greenspan emphasized the key role of financial markets in driving the economy and was leery of the intellectual hubris that underpinned Keynesian fine-tuning.

"Unlike many conservative economists in the late 1970s, Greenspan never fell in love with “rational expectations.”

"Unlike many conservative economists in the late 1970s, Greenspan never fell in love with “rational expectations.”

77/ "In its earliest versions, rational expectations argued that fiscal and monetary policy could be powerless. (If the government ran a budget deficit to stimulate growth, rational individuals would prepare for the higher taxes by saving more, negating the intended stimulus.)

78/ "Greenspan agreed that fine-tuning was counterproductive, but he did not agree that it was impotent.

"By ignoring the impact of asset prices on spending, Greenspan contended, the reigning forecasting models were “abstracting from reality in a somewhat unrealistic manner.”

"By ignoring the impact of asset prices on spending, Greenspan contended, the reigning forecasting models were “abstracting from reality in a somewhat unrealistic manner.”

79/ "Capital gains/losses were not part of national income accounts; their absence “tended to bias model builders away from data not readily available.” Still, economists ought to do better: he cited the impact of home-equity extraction, “largely missed in the standard models.”

80/ "It also worked the other way around: higher spending could boost prices. Eventually, feedback loops would drive prices to unsustainable levels, and the bubble would burst. In the heyday of EMH faith, Greenspan did not believe that markets were always rational." (p. 212)

81/ "Years before critics charged that the Fed had been blind to wealth effects and bubbles, Greenspan was at the cutting edge of these questions.

"Post-2008, underestimating finance was held up as one of economics’ errors. But he was never guilty of this mistake." (p. 213)

"Post-2008, underestimating finance was held up as one of economics’ errors. But he was never guilty of this mistake." (p. 213)

82/ "By the mid-1970s, Greenspan noted, rising interest rates no longer had the expected effect. The Fed had just increased the short-term interest rate to 9%, but mortgages were still easy to come by, and house prices were booming.

83/ "In 1970, Fannie Mae had been allowed for the first time to buy private mortgages. In the same year, Congress created Freddie Mac. Goading each other on, Fannie and Freddie bought mortgages from banks and S&Ls, such that these lenders gained a huge new source of funds.

84/ Greenspan: “The mortgage market has basically exploded into a major new financial vehicle that dwarfs the federal deficit, dwarfs corporate borrowing, and dwarfs state and local borrowing. It has become the most dominant element in the whole financial system.”

85/ "This had not merely delinked housing from rates; it had temporarily delinked the whole economy.

"In 2008, Greenspan's implication was that the Fed had been nearly powerless to defuse the housing bubble—rates for long-term mortgages were barely responding to short rates.

"In 2008, Greenspan's implication was that the Fed had been nearly powerless to defuse the housing bubble—rates for long-term mortgages were barely responding to short rates.

86/ "But this breakdown was less novel than he implied. As he had written in his PhD thesis, shifts within finance constantly altered the economy’s behavior. Foreign bond purchases in the 2000s provided one example. Fannie and Freddie in the 1970s provided another." (p. 219)

87/ "Greenspan doubted that real-world relationships remained stable long enough to justify spending months to tweak a single equation: each part of the economy reflected multiple influences that were constantly in flux.

88/ "For example, household spending might be driven by house prices or job prospects or fears of inflation or any number of factors, and the drivers that most mattered would vary from one period to another.

89/ "He mistrusted grand hypotheses about how the economy functioned. He was not interested in what ought to happen according to some elegant theory; he was interested only in what would happen as a result of messy reality.

90/ "Even if none of the relationships was fixed or certain, each contained a useful hint. If you collected enough canaries, you got a sense of what might happen in the coal mine.

91/ "Because he was not dazzled by theory, he felt free to focus on data—on ferreting out information that others did not have rather than obsessing about the mathematical assumptions that linked the data points together." (p. 221)

92/ "The delinking of rates from mortgage lending was not absolute; in the end, the Fed hiked enough to make an impact. At the start of 1979, with the Fed’s short-term policy rate now at 10%, mortgage lending started to fall, silencing the engine that had propelled consumption.

93/ "Price controls and other regulatory meddling had suppressed investment and productivity gains, dampening growth; meanwhile, they created bottlenecks, fueling inflation. The resulting stagflation left policy makers wondering whether to stimulate or to apply brakes." (p. 223)

94/ "Greenspan’s new stance seemed logical. It would be futile to go back to the gold standard so long as inflation raged: inflation would undermine the credibility of the gold peg. And if inflation could in fact be contained, going back to gold would have been shown unnecessary.

95/ "Modern pluralistic systems, Greenspan was saying, were messy and willful; after witnessing government up close, he knew this conclusively. It was idle to expect such systems to submit to rules—political pressures would destroy them." (p. 227)

96/ "Because of manifold uncertainties about the economy and the financial system, monetary experts could not be expected to speak with one voice. Mustering the intellectual consensus necessary to defy political pressures was therefore all but impossible." (p. 230)

97/ "In October 1979, consumer price inflation was running at 12.1%; three years later, when Volcker ended his experiment with monetary targets, the rate had plummeted to 5.9%. To force inflation down, round upon round of tightening proved necessary.

98/ "In the summer of 1981, short-term interest rates breached 20%, prompting Representative Henry González to denounce Volcker for “legalized usury beyond any kind of conscionable limit.” The economy endured a double-dip recession, and unemployment hit double digits, too.

99/ "But the payoff was clear. Inflation not only halved during Volcker’s three-year monetarist experiment, it kept falling into 1983. By dint of iron-willed persistence, Volcker turned the inflationary 1970s into the disinflationary 1980s.

100/ "Bankrupt home builders protested by mailing two-by-fours to his office; carmakers sent him the keys of unsold vehicles; furious farmers encircled the Fed’s headquarters.

"Volcker refused to shrug off his responsibility, even when lawmakers threatened to impeach him.

"Volcker refused to shrug off his responsibility, even when lawmakers threatened to impeach him.

101/ "Month after month, the giant sat stoically through furious congressional hearings, occasionally shaking his domed head as if to say that he pitied the simpletons who abused him. “I’ve always considered him the most important Chairman,” Greenspan said, years later." (p. 233)

102/ "Volcker did not so much lead as wait for panic in the markets to do the leading for him.

"In 1951, the Fed stood firm against Truman because inflation hit 20%. In 1979, 12% inflation plus a crashing dollar gave Volcker the chance to show his greatness." (p. 234)

"In 1951, the Fed stood firm against Truman because inflation hit 20%. In 1979, 12% inflation plus a crashing dollar gave Volcker the chance to show his greatness." (p. 234)

103/ "Greenspan had nothing but respect for Volcker, but he regretted that the fight against inflation had not been pressed further. If the goal was to discipline wild money creation, the government needed to clamp down on federal subsidies for mortgages." (p. 235)

104/ "Greenspan had long favored tax cuts, but Reagan embraced these naïvely—without any of the spending cuts that would make them affordable. From Greenspan’s perspective, Reagan was congenial in his small-government instincts but alarming when it came to policy detail.

105/ "In late 1979, Greenspan collaborated with Fortune on a long-run economic forecast, correctly predicting that falling inflation, lower corporate taxes, and deregulation would boost the incentives for business investment, turning the 1980s into a boom era." (p. 238)

106/ "When he surveyed the policy landscape, the conservative Greenspan could see a Democratic Fed chairman, Paul Volcker, who embodied his own hard-money ideals; he could see a Democratic Senate banking chairman, William Proxmire, who embodied his budget conservatism." (p. 240)

107/ "Greenspan worked up estimates of how much extra growth and government revenues the tax cuts would really generate, concluding that every $100 in cuts would generate only $17 in new revenues, meaning that they would expand the budget deficit by $83.

108/ "It followed that Reagan’s tax plan would be affordable only if it was phased in slowly, with deep spending reductions in the meantime. But Reagan was trapped. He had already promised tax cuts, a balanced budget, and a defense buildup besides." (p. 251)

109/ "Stockman told Weidenbaum to plug in whatever inflation number he could live with. He just wanted the estimate for growth to be as high as possible because high growth would make the future deficits look manageable.

110/ "Weidenbaum’s high-inflation, high-growth forecast had allowed Stockman to balance the budget on paper; but when the forecast proved wrong, the low-inflation, negative-growth reality depressed tax receipts, delivering a budgetary calamity.

111/ "Greenspan’s political antennae had served him well. By hiding behind proxies and picking his battles, he had avoided association with a fiscal humiliation.

"For top officials, even for the Treasury secretary, there was not much glory in presiding over the budget." (p. 259)

"For top officials, even for the Treasury secretary, there was not much glory in presiding over the budget." (p. 259)

112/ 1981: "The revered Social Security system, which mailed regular checks to thirty-six million beneficiaries, was running short of cash; if nothing was done before the spring of 1983, there would be insufficient revenues to keep the checks flowing." (p. 272)

113/ 1983: "The Dole-Moynihan cabal agreed on pragmatic fiddles to extend Social Security’s solvency into the 1990s. Cost-of-living increases would be delayed; scheduled payroll tax increases would be brought forward; affluent retirees would pay taxes on their benefits." (p. 279)

114/ 1982: "Mexico's stash of foreign currency was dwindling by the hour. It would default when the markets opened on Monday.

"America’s top banks had lent Mexico so much that the country’s default now threatened their own viability.

"America’s top banks had lent Mexico so much that the country’s default now threatened their own viability.

115/ "The battle against inflation had rendered some kind of debt crisis almost inevitable. Before Volcker’s policy revolution, borrowers had taken on debt carelessly, believing that inflation would erode its real value, but after the Volcker revolution, inflation fell.

116/ "The $3.5 billion rescue for Mexico staved off an immediate banking collapse but did not eliminated the risk of some future meltdown, especially because a sharp recession at home was driving thousands of borrowers into bankruptcy, adding to the banks’ losses.

117/ "Having abandoned monetary targets, Volcker could hardly pretend that high rates were not his doing. He had replaced the rule with nothing more concrete than his personal judgment.

"It was his judgment against Friedman’s. Nobody defended him." (p. 285)

"It was his judgment against Friedman’s. Nobody defended him." (p. 285)

118/ "Proving incapable of anger and not giving offense, Greenspan had built a vast network with anyone who was anyone. He had risen to prominence as the man who knew. Now that the Fed chairmanship appeared to be open, the key to his stature was that everybody knew him." (p. 288)

119/ "Western banks had already been battered by the Latin American shock, and now Continental’s woes threatened to push them over the edge. In the American Midwest, some fifty banks were said to have deposits at Continental that exceeded their total capital.

120/ "The Fed, which had been founded after 1907 precisely to end the unnerving reliance on private bailouts, had created the stability that had allowed finance to expand. As a result, when crises did occur, they happened on a scale that demanded Fed action.

121/ "Even the Churchillian Paul Volcker had followed that path. On Mexico and again on Continental Illinois, he had thrown public money at defaulters and allowed private creditors to escape unscathed. The doctrine of “too big to fail” had been established." (p. 301)

122/ "In the laissez-faire 19th century, banks had needed ample capital to attract deposits; in the paternalistic late 20th century, depositors knew that the government insured them, so capital was passé.

"But Greenspan retained more faith in financiers than in regulators.

"But Greenspan retained more faith in financiers than in regulators.

123/ "A bank’s judgment about how much capital to hold was distorted by the government backstop; but a regulator would fail to reckon with even simple matters like the duration of a bank’s borrowings or the riskiness of its lending. They might well be worse than banks." (p. 302)

124/ " “Life is risky,” Greenspan concluded at the New York Times forum in the summer of 1984.

"Despite the many financial disasters that ensued, this passive bottom line remained the best that he could offer." (p. 304)

"Despite the many financial disasters that ensued, this passive bottom line remained the best that he could offer." (p. 304)

125/ "Just as Greenspan thought Prell underestimated how economic relationships could shift, Prell thought Greenspan underestimated the limits to statistics. Greenspan was like a man who squeezes a lemon long after the juice is gone from it.

126/ "If the data were only approximate, it was unscientific to suppose that clever adjustments could make them more accurate. And if the distortions that bothered Greenspan were always present, they could be safely ignored because forecasters cared about the changes." (p. 335)

127/ "Before arriving at the Fed, Greenspan had noted repeatedly that an extraordinary buildup of debt was making the economy more vulnerable. American households were devoting three times more of their income to interest payments than they had at the end of the Korean War.

128/ "Nonfinancial corporations had allocated 10% of earnings to interest payments in the mid-1950s; now that share had leaped to 60%. This leveraging of America had lifted the economy to new heights, facilitating a burst of investment and spending.

129/ "But because families and firms were on the hook to pay back debts, they were constantly at risk of bankruptcy.

"Just when Volcker had established the Fed’s inflation-fighting credibility, leveraged finance might force his successor to abandon it." (p. 344)

"Just when Volcker had established the Fed’s inflation-fighting credibility, leveraged finance might force his successor to abandon it." (p. 344)

130/ "EMH had dominated academia since the late 1960s. But statisticians pointed out that extreme falls occurred far more commonly than assumed in the equations. Behavioral economists invoked experiments showing limits to rationality." (p. 360)

More:

More:

https://twitter.com/ReformedTrader/status/1317876706414227457

131/ "Greenspan had never bought into the efficient markets hypothesis, but there were other lessons from the crash that challenged his thinking. Black Monday forced him even further from his youthful conviction that central banks ought to allow private financiers to go bust.

132/ "To the extent investors were waking up to real risks, a sharp market correction could be salutary. But panic was likely to feed upon itself. The Fed’s strategy during Black Monday had been “aimed at shrinking irrational reactions in the system to an irreducible minimum.”

133/ "The leveraging of America had been accompanied by the emergence of a financial system that simply had to be propped up—it was not just individual banks that were too big to fail; the whole nexus of exchanges, brokers, and clearinghouses collectively fitted that description.

134/ "Stock market panics in the pre-Fed era had dragged down the economy because they had triggered a reinforcing jump in interest rates; during the panics of 1893 and 1907, brokers had been forced to endure borrowing costs as high as 74%.

135/ "But now, an activist Fed could clean up the mess left by a bursting bubble. Greenspan could worry about bubbles a little less obsessively and focus his efforts on targeting lower inflation.

"The crash of 1987 led, paradoxically, to less fear of a crash." (p. 362)

"The crash of 1987 led, paradoxically, to less fear of a crash." (p. 362)

136/ "If speculators thought that the Fed had their backs, their bets would only grow wilder. By the end of his tenure, Greenspan was remembered as the creator of the “Greenspan put.” But in 1989, he was furious with Johnson for announcing such a put in public." (p. 385)

137/ "Critics who later scolded Greenspan for monetary policy that enabled bubbles and for a regulatory stance that permitted Wall Street to run wild seldom reckoned with the early part of his tenure.

"He raised the discount rate on the eve of the Republican convention in 1988.

"He raised the discount rate on the eve of the Republican convention in 1988.

138/ "He brushed off warnings from a popular new president by hiking the fed funds rate in 1989. When the White House budget director came after him, Greenspan refused to budge, even as New England’s housing bubble imploded and S&Ls failed across the nation.

139/ "The cost of the S&L cleanup increased, and the budget deficit ballooned alarmingly.

"Soon, Bush’s three-word campaign centerpiece of “no new taxes” had fallen victim. The president had been forced into a U-turn. He was ready to raise taxes after all." (p. 389)

"Soon, Bush’s three-word campaign centerpiece of “no new taxes” had fallen victim. The president had been forced into a U-turn. He was ready to raise taxes after all." (p. 389)

140/ In Greenspan’s opinion, Saddam had to be confronted. He then advanced his monetary prescription: do nothing. War would presumably increase the odds of a recession, but Greenspan spun a story about how a do-nothing policy would send a reassuring signal to the world." (p. 394)

141/ "For most of the postwar era, the economy had contracted when the Fed had raised rates. With less borrowing and spending, businesses got stuck with unsold goods; they cut production and waited for inventories to run down. The consequent layoffs rippled through the economy.

142/ "But in 1990, the problem was not high rates but high debt. The economy was slowing not simply because the Fed disciplined credit but because overextended banks and customers disciplined themselves.

"This was what economists later called a balance-sheet recession." (p. 400)

"This was what economists later called a balance-sheet recession." (p. 400)

143/ "Facing pressure from the White House and his FOMC colleagues, Greenspan could usually rely on his standing with the press and in Congress. If newspapers praised him and senators hung upon his words, there was a limit to what his enemies could do to him.

144/ "With Andrea Mitchell’s assistance, Greenspan had taken to staging elaborate Fourth of July parties on the grand balcony of one of the Fed’s buildings; senators mingled with Supreme Court justices and leading members of the press." (p. 402)

145/ "Greenspan had spent much of his career lamenting that banks would act prudently only in a parallel world with no government bailouts, no lender of last resort, and no deposit insurance.

"But the too-big-to-fail problem was far less tractable than he now pretended." (p.408)

"But the too-big-to-fail problem was far less tractable than he now pretended." (p.408)

146/ "By running a gun-shy policy after the 1987 crash, Greenspan had allowed the economy to overheat, setting the stage for the 1990–91 recession. He had then stuck with the hard-man approach too long, underestimating the drag on the recovery from the real estate bust." (p.416)

147/ “This is a town full of evil people. If you can’t deal with people trying to destroy you, you shouldn’t think of coming.”

"But the truth was that Greenspan courted politicians assiduously. The Fed needed to remain on cordial terms with Congress and the White House." (p.418)

"But the truth was that Greenspan courted politicians assiduously. The Fed needed to remain on cordial terms with Congress and the White House." (p.418)

148/ "Though Greenspan had more confidence in markets than any previous chairman, he could only guess at their right level. To raise rates in the face of a bubble is to pay a certain price to head off an uncertain threat—incurring the wrath of politicians and the public." (p.430)

149/ "In most circumstances, short rates drove long ones. Prell’s staff tested the correlations going back four decades: Even during the 1980s, when inflation and inflation expectations had been on everybody’s minds, their influence on long-term interest rates had been marginal.

150/ "Low inflation might offer a false signal for monetary policy. The CPI appeared stable because imports were getting cheaper: low-cost emerging nations were joining the world economy; globalization restrained prices for everything that could be traded.

151/ "In this environment, the Fed could supply a surprising amount of easy money without being punished by inflation. But it did not necessarily follow that easy money was desirable. As Lindsey reminded his colleagues, low rates prevented savers from earning a return on cash.

152/ "It induced wealthy Americans to shovel savings into equities, commodities, real estate, and bonds. People were tempted to borrow imprudently. The resulting asset bubbles and towers of household debt could upset the smooth path of the economy just as surely as inflation.

153/ "By refusing to respond to the evidence of a bubble, Greenspan was neglecting a potential danger to the economy’s progress. By defining the Fed’s mission narrowly in terms of price stability, he risked fighting the last war—the war of the 1970s." (p. 436)

154/ "Clinton was not like his predecessor: he was not going to come after Greenspan, even in private. Whatever Clinton’s reputation for baby-boomer indulgence, he was the most disciplined president in memory when it came to Fed independence." (p. 437)

155/ "In the new deep and global capital markets, a hike in the federal funds rate would have a significant effect only if traders reacted by bidding up market interest rates.

"If the Fed wanted to play the influence game, it would have to speak clearly and publicly." (p. 437)

"If the Fed wanted to play the influence game, it would have to speak clearly and publicly." (p. 437)

156/ "Reacting to a cut in the short-term rate by gobbling up bonds and driving down the long-term rate, traders amplified the Fed’s decision to loosen—precisely what the Fed wanted. In the wake of the crippling losses at traditional lenders, hedge funds were especially useful.

157/ "By borrowing short and lending long, they stood in for wounded banks. But hedge funds’ amplification of monetary policy could be alarming, too—particularly because the power of the amplifier was variable and unpredictable.

158/ "A fall in the bond market of just 1% would wipe out Steinhardt’s entire equity stake, so he had to bail at the first sign of trouble. Once the rush began, it cascaded unpredictably. Increased margin requirements put Wall Street into shock.

159/ "This was mirrored by losses on the bond-trading desks of the big banks. Trading in shares of J.P. Morgan and Bankers Trust was temporarily suspended.

"The insurance industry lost as much money on its bond holdings as it had paid out for damages following Hurricane Andrew.

"The insurance industry lost as much money on its bond holdings as it had paid out for damages following Hurricane Andrew.

160/ "Thanks partly to Greenspan's prodding, Clinton had risked his political capital on deficit reduction, betting the bond market would reward him. But the 5-year rate was now higher than it had been when he was elected, and the 10-year rate was almost unchanged." (p. 443)

161/ "For much of the 2000s, Greenspan moved interest rates steadily and predictably, telegraphing his intentions via speeches, congressional hearings, and the FOMC’s postmeeting statements.

"The impact of his transparency was exactly as he had anticipated in 1994.

"The impact of his transparency was exactly as he had anticipated in 1994.

162/ "Traders were emboldened to leverage their portfolios, confident that the cost of borrowing would not move against them unexpectedly. If the Greenspan of 2004 had acted on the Greenspan observation of 1994, the bubble of 2006 might have been less disastrous." (p. 445)

163/ "At Alan Blinder’s first FOMC meeting, he appeared understandably bemused: the most august group of monetary policy makers in the world seemed somewhat at sea about the basics of its mission." (p. 452)

164/ "Paul Krugman would observe, “One of the dirty little secrets of economic analysis is that even though inflation is universally regarded as a terrible scourge, efforts to measure its costs come up with embarrassingly small numbers.” " (p. 454)

165/ "More than anybody cared to notice, Greenspan's success reflected luck: if consumer price inflation stood at an impressively low 2.7% at the end of 1994, down from 6.3% on the eve of the Gulf War, this success had materialized despite significant errors.

166/ "The Fed had underestimated the credit crunch of 1991–92 and so had run tighter policy than it had intended. It had misread the economy in 1993, wrongly attributing declining long-term interest rates to falling inflation expectations.

167/ "And yet deeper forces conspired to bring down inflation: global competition, advancing technology, declining labor-union membership. In this unfamiliar new economy, periods of monetary looseness were more likely to result in bubbles than in consumer price spikes.

168/ "But nobody bothered with such obscure quibbles. Greenspan was presiding over low inflation and strong growth. His reputation prospered marvelously." (p. 463)

169/ "Sanford’s fuzzy grasp of his own bank’s products raised a question for Greenspan. Finance had grown so complex that risk-takers no longer understood their own portfolios.

"The sorcerers at Bankers had deliberately dreamed up products their clients could not understand.

"The sorcerers at Bankers had deliberately dreamed up products their clients could not understand.

170/ "Bankers employees referred routinely to the “rip-off factor” in their deals: “Lure people in and then totally f*** ’em.”

"Orange County had got its fix of poison courtesy of Merrill Lynch, suggesting that the whole business of designer swaps might be a cauldron of trouble.

"Orange County had got its fix of poison courtesy of Merrill Lynch, suggesting that the whole business of designer swaps might be a cauldron of trouble.

171/ "The complexity of the most exotic contracts made it easy to rip off clients: this lesson emerged from the abusive selling of toxic mortgage securities before the 2008 crash, but the same lesson could have been learned more than a decade earlier.

172/ "Complexity also made it possible for crazy risks to build up inside financial enterprises, unbeknownst to their own managers. This was the lesson from 2008 in the venerable AIG insurance, laid low by derivative sorcerers. But the same thing might have been learned in 1994.

173/ "But getting financial regulation right was virtually impossible. Volcker had failed at it, and Greenspan might too.

"To a politically astute Fed chairman, the smart course was to avoid entanglement in regulation in the first place." (p. 470)

"To a politically astute Fed chairman, the smart course was to avoid entanglement in regulation in the first place." (p. 470)

174/ "Greenspan had been central to the Mexico rescue. The result was another step in his emergence as a maestro.

"The Fed chairman had the respect of the media and of the newly powerful Republicans in Congress. He was prepared to use his influence to advance Clinton’s projects.

"The Fed chairman had the respect of the media and of the newly powerful Republicans in Congress. He was prepared to use his influence to advance Clinton’s projects.

175/ "Traditionalists were appalled by the expansion of moral hazard: the Fed chairman was guilty of “providing long-term financing to another country that has mismanaged its financial affairs,” St. Louis Fed president Thomas Melzer complained." (p. 478)

176/ Greenspan, 1995: “The real danger is that things get too good. When things get too good, human beings behave awfully.”

"He understood it before Minsky was in vogue—at a time when most of economics erroneously believed that macro stability bred financial stability." (p. 480)

"He understood it before Minsky was in vogue—at a time when most of economics erroneously believed that macro stability bred financial stability." (p. 480)

177/ "The key figures in the Senate had got into the habit of formulating economic opinions by first asking Greenspan where he stood; he was the man who knew, and they would not stray far without consulting him." (p. 486)

178/ "The supposed drawbacks to clarifying the Fed's long-term objective were receding. Earlier, Yellen had resisted an inflation target because of the presumed sacrifice of jobs. Now, with falling inflation plus falling unemployment, that sacrifice seemed to have evaporated.

179/ "She had argued that an inflation target might squander the Fed’s credibility because the Fed might announce a target and then miss it. Now, with inflation falling almost magically, the risk of missing seemed modest.

180/ "Years later, it would be said that the Fed’s conversion to inflation targeting had brought inflation down. But causality flowed equally in the opposite direction. Falling inflation brought the FOMC to the point where it was ready to embrace inflation targeting." (p. 488)

181/ "There had been no collective epiphany—no moment of lucidity when the committee had decided on its new objective because of the force of the arguments.

"It did not come about because the FOMC could prove there were large benefits from suppressing inflation.

"It did not come about because the FOMC could prove there were large benefits from suppressing inflation.

182/ "Yellen had lectured the committee on the lack of such evidence, and nobody contradicted her.

"From July 1996 on, the Fed’s leaders aimed to get inflation down to a somewhat arbitrary 2%, though they were not entirely sure what they would do when they got there." (p. 490)

"From July 1996 on, the Fed’s leaders aimed to get inflation down to a somewhat arbitrary 2%, though they were not entirely sure what they would do when they got there." (p. 490)

183/ 1995: " “Stocks are selling at unbelievable multiples of earnings and revenues. Companies are going public that don’t even have earnings,” a Wall Streeter protested. Americans seemed to be entering one of those phases when they forgot that bad things could happen." (p. 491)

184/ "Unlike a demand shock, a supply shock—a sudden change in the economy’s capacity to produce things—confronted the Fed with a trickier problem, as inflation & the economy would move in opposite directions. This dilemma came to be well-recognized by monetary experts." (p. 496)

185/ "Despite what he asserted later, Greenspan shrank from acting against the 1990s stock bubble not becuse it was impossible to identify or impossible to pop. It was simply that, for an inflation-targeting central bank, worrying about bubbles was a secondary priority." (p. 498)

186/ "The tragedy of Greenspan’s tenure is that he did not pursue his fear of bubbles far enough. He decided that targeting inflation was seductively easy, whereas targeting asset prices was hard. He did not like to vaporize citizens’ savings by forcing prices down." (p. 506)

187/ "As the baht followed the greenback up, Thailand lost competitiveness. To pay for the excess of imports over exports, Thailand had to borrow from foreigners. But this strategy could be sustained for only so long.

"It was a matter of time before the currency peg shattered.

"It was a matter of time before the currency peg shattered.

188/ "They sold baht aggressively, and their prophecy fulfilled itself. On July 1, 1997, the peg broke, and the currency began a headlong fall, causing the economy to shrink by one-sixth and transferring more than $1 billion of Thai savings from the central bank to speculators.

189/ "Once Thailand fell, the panic spread to its neighbors. In August, Indonesia was forced to let its currency fall by 11%, and Malaysia came under attack from the markets.

"South Korea's finance minister had recently been fired for suggesting an emergency loan from the IMF.

"South Korea's finance minister had recently been fired for suggesting an emergency loan from the IMF.

190/ "Nearly all of Korea’s foreign-currency reserves were gone. They had already been used to prop up the country’s banks, which needed dollars to replace loans from global lenders that were running from Korea." (p. 515)

191/ "Banks were ready to roll over their loans to rather than demanding their money back.

"But this “private” initiative was the result of government muscle. And the provision of official loans to Korea meant that taxpayers were helping protect the bankers from their follies.

"But this “private” initiative was the result of government muscle. And the provision of official loans to Korea meant that taxpayers were helping protect the bankers from their follies.

192/ "Rubin called attention to Greenspan’s backing—if a libertarian Republican helped to formulate the Korea plan, surely it could not be welfare for bankers. So, strangely, Greenspan emerged as a key architect of a policy about which he had initially expressed ambivalence.

193/ "There would be lasting implications for his reputation.

"By the spring of 1998, South Korea was on the mend. Whether Greenspan liked it or not, the Fed was emerging as the central banker to everybody." (p. 521)

"By the spring of 1998, South Korea was on the mend. Whether Greenspan liked it or not, the Fed was emerging as the central banker to everybody." (p. 521)

194/ March 1998: "The economy might be approaching that phase when a boom descends into self-parody. Unemployment was at 4.6%, its lowest rate in 25 years, and workers with particularly sought-after skills were dashing from one employer to the next in search of ever-higher pay.

195/ "Greenspan conceded that “the economy’s performance is absolutely unusual.” The market had “an utterly unrealistic expectation” of earnings. Risky companies borrowed at rates scarcely higher than those on government bonds. Bank officers behaved as though risk had vanished.

196/ " “There is too little uncertainty in this system. Human nature has not changed, and when it reasserts itself, things are going to look a lot different.”

"But for the time being, he continued, inflation remained quiet; there was no harm in waiting to raise rates." (p. 523)

"But for the time being, he continued, inflation remained quiet; there was no harm in waiting to raise rates." (p. 523)

197/ "Thanks to computerization, companies knew how many parts to order and how many widgets to ship to each outlet; old bottlenecks were gone, and with them, a main driver of inflation. “This is the best economy I’ve ever seen in fifty years,” Greenspan assured Clinton." (p.526)

198/ "CNBC was one of several cable news channels that sprang up in the 1990s, hungry for daytime fodder to feed their audiences of day traders. The oracular Fed chairman was a ratings godsend; his least significant remarks were carried live and unexpurgated.

199/ "The U.S. was reclaiming a preeminence not seen since the aftermath of WWII. The USSR had disintegrated. Japan was experiencing its first lost decade. China was too poor to pose a threat. West Germany was resting after swallowing up its eastern neighbor." (p. 529)

200/ "Greenspan wanted to avoid the error of supposing that just because an absence of regulation entailed risk, the imposition of regulation would reduce it.

"History was littered with examples of regulation that misfired.

"History was littered with examples of regulation that misfired.

201/ "The 1960s caps on rates had caused savings to flee to Europe, spawning the Eurodollar market; similarly, a precipitate lunge against OTC derivatives might drive them to London.

"In the absence of regulation, traders would be motivated to monitor their own risks." (p. 534)

"In the absence of regulation, traders would be motivated to monitor their own risks." (p. 534)

202/ "Letting LTCM suffer was essential to Greenspan’s laissez-faire vision. He could scarcely trust traders to manage their own risks while simultaneously dulling their incentives to be prudent. But not for the first time, Greenspan lacked the fortitude to live up to his vision.

203/ "His cult status had come to depend on continual growth, exuberant finance, and miraculously low unemployment. His identity had fused with the national expectation of prosperity without limit. He was imprisoned by his reputation." (p. 535)

204/ "Because swaps were not traded on exchanges, they had no clear price; during stress, they could be impossible to exit. Panic fed on itself; there was no central clearing system to guarantee payments. Nobody wanted to strike deals with shops that could blow up at any moment.

205/ "Every asset in LTCM’s possession had been pledged as collateral to a lender or trading partner. In the event of a default, the counterparties would seize everything and probably sell immediately." (p. 539)

206/ "The Fed had contended that OTC traders could police their own risks. But LTCM had underlined the danger in these chains of paper promises.

"Just about every major creditor on Wall Street had thrown money at Long-Term Capital, even though its strategy was built on hubris.

"Just about every major creditor on Wall Street had thrown money at Long-Term Capital, even though its strategy was built on hubris.

207/ Greenspan: “It is one thing for one bank to have failed to appreciate what was happening. But this list of institutions is just mind-boggling.”

"Finance would never be fail-safe, as Greenspan correctly understood. But it could perhaps be rendered safer to fail.

"Finance would never be fail-safe, as Greenspan correctly understood. But it could perhaps be rendered safer to fail.

208/ "OTC derivatives could be centrally cleared so that panic in one fund would not spread panic to the rest; simpler banks could be favored over complex ones. Yet Greenspan showed no inclination to explore this middle way." (p. 541)

More on this:

https://twitter.com/ReformedTrader/status/1271108014498385920

209/ "After watching LTCM’s partners lose their personal wealth, other hedge-fund managers generally avoided crazy leverage over the next decade.

"After seeing the fund’s creditors forced to pick up the pieces, banks grew more careful in how they financed hedge-fund trading.

"After seeing the fund’s creditors forced to pick up the pieces, banks grew more careful in how they financed hedge-fund trading.

210/ "Come 2008, free-standing hedge funds (as distinct from those whose discipline was compromised by deep-pocketed banking parents) emerged as one of the more stable parts of the financial system." (p. 545)

211/ "Priceline had begun operations just one year before, and for anyone who paused to contemplate its headlong rise, it stood as a warning. The company consisted of virtually no assets, an untested brand name, and fewer than two hundred employees.

212/ "In its first eight months, sold $35 million worth of discounted air tickets—for which it had paid $36.5 million. On top of this $1.5 million operating loss, Priceline had burned upwards of $100 million on Web development, marketing, and free stock options for suppliers.

213/ "By one reckoning, the company had incinerated $114 million of investors’ money. It experimented with selling car rentals, hotel rooms, and mortgages on their Web site. They rented a ballroom in a Manhattan club and pitched a vision of a cyberretailing empire to investors.

214/ "Amid the Wall Street euphoria, every go-go fund manager wanted a piece of the action. On its first day of trading (March 30, 1999), Priceline’s value quadrupled to $10 billion—more than United Airlines, Continental Airlines, and Northwest Airlines put together." (p. 549)

215/ "George W. Bush’s proposed tax cut seemed eminently affordable. The budget office’s projection, however, was just that: a projection. Anybody who recalled the disastrous budget forecasts of the early Reagan years would treat it with caution.

216/ "The economy had slowed, driving the Fed to announce a hefty rate cut of 50 bps. A weaker economy meant weaker tax revenues. Just as the windfall from the Greenspan boom had fueled the budget surplus, a prolonged slowdown might cause the surplus to evaporate." (p. 573)

217/ "Early in his campaign, Bush had advocated the tax cut mostly on the ground that the nation was booming—if the proceeds of the surplus were not returned to the people, Congress would lavish the money on big-government programs.

218/ "Now Cheney thought the tax cut could be sold on the opposite theory. According to the vice president’s logic, if the economy slowed even more sharply and the budget deficit returned with a vengeance, that would be all the more reason to press ahead with tax cuts." (p. 575)

219/ "The Fed bet its reputation on the proposition that it could clean up after a bubble; if it succeeded, perhaps the downturn would be mild enough for the earlier boom to have been worth it. Recognizing the stakes, Greenspan loosened policy aggressively from the start of 2001.

220/ "The ferocity of the Fed’s action carried a warning. Perhaps, in the face of some future financial implosion, the Fed might run out of space to ease? Perhaps rate cuts this rapid and this deep might risk unpleasant side effects?

221/ " “Banks in our region are beginning to lend more aggressively on real estate,” Tom Hoenig, the president of the Kansas City Fed, observed at the FOMC meeting in March 2001. Low interest rates “might cause some—for lack of a better word—overbuilding.” " (p. 581)

222/ 9/11/2001: "Thanks to the heroic efforts of the Fed’s staff, the discount window was on its way to pumping $37 billion into the country’s banks by the end of that first day: nearly two hundred times more than the Fed normally lent. Black Monday looked trifling by comparison.

223/ "Faced with disruptions to the nation’s check-clearing system, the Fed announced that it would shoulder the “risk of ride”: banks receiving checks would get their money from the Fed immediately, even before the paying banks had made good on their obligations.

224/ "The Fed also stemmed the panic among foreign financial institutions. It lent to the central banks of Britain, the Eurozone, and Canada, allowing them to support domestic lenders that found themselves abruptly short of dollars.

225/ "Thus far, the Fed had averted disaster. But there were still many unknowns. The trading floors of several exchanges had suffered structural damage. In the bond market alone, data representing $170 billion worth of trades were missing." (p. 586)

226/ "The attacks of 2001 brought an end to the euphoric mood of the 1990s. It turned out that dot-com companies were not actually building a utopia with America at its apex; it turned out that the symbols of U.S. preeminence could become propaganda props for terrorists." (p.590)

227/ "Business investment collapsed. Before, it had been held back by the overhang of excess investment during the tech boom; now the overhang was compounded by the unfamiliarity of a new world, one in which goods no longer rolled across borders without paranoid inspection.

228/ "Core inflation fell to 1.2% in the month of the attacks. In November, the University of Michigan reported that inflation expectations had plunged to 0.4%. (In thirty-five years of tracking inflation expectations, the Michigan survey had never recorded a reading below 1%.)

229/ "Summarizing the research literature, Kohn told the FOMC that the committee should cut rates before the impact of its cuts was undermined by deflation. An economy facing a Japan-type risk must avoid being “pinned to the lower bound.”

230/ "Greenspan might once have ridiculed Kohn’s argument, observing that deflation under the gold standard had “in no way inhibited the expansion of economic activity.” From 1865 to 1900, U.S. prices fell 1.7% per year, a far steeper decline than anything experienced in Japan.

231/ "Yet, “the latter half of the 19th century was perhaps the period of the greatest advancement in standards of living that has ever existed.” Deflation from cost-cutting new technologies might be harmless.

"By this stage, however, Greenspan’s Randian convictions had faded.

"By this stage, however, Greenspan’s Randian convictions had faded.

232/ "In 2001, the downward pressure on prices was not simply the result of tech-driven economies: the nation was suffering a sudden weakness in demand. Companies and individuals had accumulated vast debts, which would be harder to pay off in a deflationary environment.

233/ "Likewise, incomes had grown 'stickier:' unemployment benefits could be expected to embolden workers to fight cuts in wages, with the result that deflation would cause wages to increase in real terms, perhaps leading to a rise in unemployment.

234/ "Government benefits were even stickier. Pensions, disability pay, and other payments would not be cut if prices fell; the upshot would be a larger government deficit.

"Greenspan proposed that the Fed cut rates by another 50 bps to the extraordinarily low rate of 2%.

"Greenspan proposed that the Fed cut rates by another 50 bps to the extraordinarily low rate of 2%.

235/ "At the following meeting, Greenspan cut the rate again, to 1.75% . He was not going to sit on his hands and follow Japan into stagnation.

"Greenspan’s battle against deflation, running from November 2001 until June 2004, would later be debated furiously.

"Greenspan’s battle against deflation, running from November 2001 until June 2004, would later be debated furiously.

236/ "In his determination to insure the economy against a Japanese-style slump, he pushed down borrowing costs about as far as they could go. His actions fueled the climb in house prices, which reached its wildest and frothiest extremes in the two years that followed." (p. 596)

237/ "If aggressive loosening was partly to blame for the property bubble, then the tech bubble planted the seeds for the 2008 crisis.

"In 2002, the Princeton economist Paul Krugman declared, “Greenspan needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble.” " (p. 597)

"In 2002, the Princeton economist Paul Krugman declared, “Greenspan needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble.” " (p. 597)

238/ "In the wake of Enron’s failure, a parade of public corporations confessed to doctoring their accounts: evidently, the tech bubble had been sustained partly by fraud. Large companies had overstated profits by an average of 2.5 percentage points per year from 1995 to 2000.

239/ "Investors were supposed to allocate savings to companies that would use them best; there was no way to get this right without reliable corporate disclosures. There was also no way Greenspan could deliver smooth inflation and growth if corporate data were rotten." (p. 597)

240/ With Greenspan's support, "in July 2002, President Bush signed a comprehensive corporate governance reform, the most far-reaching legislative overhaul of business rules enacted since the 1930s." (p. 599)

241/ "Because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had originally been chartered by the government, and because they maintained formidable lobbying machines, investors assumed that they would never go bankrupt: they were not merely too big to fail; they were too politically connected.

242/ "Perceiving no risk in lending to Fannie and Freddie, their creditors extracted no risk premium; the reduction in borrowing costs was a subsidy worth $10 billion/year.

"No wonder Fannie & Freddie were #1 & #2 on Fortune’s list of the most profitable companies per employee.

"No wonder Fannie & Freddie were #1 & #2 on Fortune’s list of the most profitable companies per employee.

243/ "Greenspan asked: If Fannie and Freddie were assumed to enjoy a government backstop, why would counterparties bother with due diligence?

"The existence of large players insured from risk could undermine risk-management standards throughout the derivatives market." (p. 602)

"The existence of large players insured from risk could undermine risk-management standards throughout the derivatives market." (p. 602)

244/ "To keep the recovery going, Bush promoted the housing boom. In 2002, he announced a “Blueprint for the American Dream,” a plan to help poor families buy property. Stretching logic, he drew a connection between the security of home ownership and security against terror.

245/ "Bush called on Congress to boost home ownership with tax credits and grants, though the housing market was already rising at its fastest rate in over 15 years. Inducements from the building lobby and the rhetoric of the American Dream had captured both political parties.

246/ "Subprime loans generated high revenues, and Fannie and Freddie could cite them in their lobbying campaigns as proof of socially inclusivity. By helping with Bush’s initiative, they could also undo the regulatory concession they had offered under pressure from Greenspan.

247/ "Their de facto government backstop would then surely be beyond doubt.

"Fannie Mae announced one hundred new partnerships with church groups to increase home ownership among racial minorities. Freddie Mac unveiled a 25-point program aimed at minorities and immigrants.

"Fannie Mae announced one hundred new partnerships with church groups to increase home ownership among racial minorities. Freddie Mac unveiled a 25-point program aimed at minorities and immigrants.

248/ "Fannie automated the underwriting of subprime loans. Due to its Expanded Approval program, previously uncreditworthy families got mortgages. Freddie reached out to customers with “nontraditional” financial profiles, such as immigrants with no bank accounts or credit cards.

249/ "Despite his efforts to contain Fannie and Freddie, Greenspan accepted Bush’s housing drive quietly.

"The possibility of a bubble had to be weighed against other risks. Given the continuing dearth of corporate investment, real estate euphoria seemed like a necessary tonic.

"The possibility of a bubble had to be weighed against other risks. Given the continuing dearth of corporate investment, real estate euphoria seemed like a necessary tonic.

250/ "The dearth of investment reflected the glut of unused factories and fiber-optic cables—the problem was not that businesses could not afford to invest; they just did not want to. If a rate cut stimulated the economy, it would be by inducing consumers to borrow and spend.

251/ "But household debt was already 100% of disposable income, up from 72% when Greenspan had assumed office. Teating the hangover from the last bust might store up trouble for the future.

"Pushing back against naysayers, Greenspan returned to the specter of deflation." (p.605)

"Pushing back against naysayers, Greenspan returned to the specter of deflation." (p.605)

252/ "Greenspan cut rates yet again in June, from 1.25% to 1%. And then he went further. With the federal funds rate now perilously close to the zero lower bound, he embraced the manipulation of expectations he had resisted since the 1970s.

253/ "Given that there was a limit to how much he could cut short-term interest rates, he shifted to pulling down longer-term interest rates by guiding the markets about his future policy.

"Monetary policy, he would later say, is 98% talk and 2% action.

"Monetary policy, he would later say, is 98% talk and 2% action.

254/ Bernanke: “Ambiguity has its uses but mostly in non-cooperative games like poker. Monetary policy is a cooperative game. The whole point is to get financial markets on our side and for them to do some of our work for us.” (p. 611)

255/ "Rock-bottom rates, coupled with the assurance that they would remain low 'for a considerable period', achieved what they were supposed to. In Q4 2003, the number of outstanding subprime mortgages doubled. The home-ownership rate climbed to 68.5%, an all-time high." (p. 614)

256/ "In the past, borrowers with slightly dubious credit had turned to subprime lenders and paid larger amounts of interest; this reflected healthy innovation & reasonable flexibility.

"Now, borrowers with truly awful credit could borrow without even documenting their earnings.

"Now, borrowers with truly awful credit could borrow without even documenting their earnings.

257/ "Before, borrowers with temporarily low incomes—a couple when one partner was in college—could get a low temporary rate.

"Now ARMs offered an early repayment holiday in exchange for punitive rates later with no reason to expect borrowers’ incomes to rise commensurately.

"Now ARMs offered an early repayment holiday in exchange for punitive rates later with no reason to expect borrowers’ incomes to rise commensurately.

258/ "The old practice of requiring home buyers to make a down payment out of their own savings was also thrown to the four winds." (p. 616)

Thread with counterpoint: "Fraudulent prime loans were more of an issue than subprime loans."

Thread with counterpoint: "Fraudulent prime loans were more of an issue than subprime loans."

https://twitter.com/ReformedTrader/status/1368008790520438784

259/ "By the middle of 2004, the mortgage industry was on track to pump out almost double the volume of subprime loans it had made one year earlier.

"One-third of subprime mortgages were being extended without meaningful assessments of borrowers’ financial status.

"One-third of subprime mortgages were being extended without meaningful assessments of borrowers’ financial status.

260/ "Thanks to computerized mortgage underwriting, default risks could be calibrated without formal documentation of income, or so the lenders asserted.