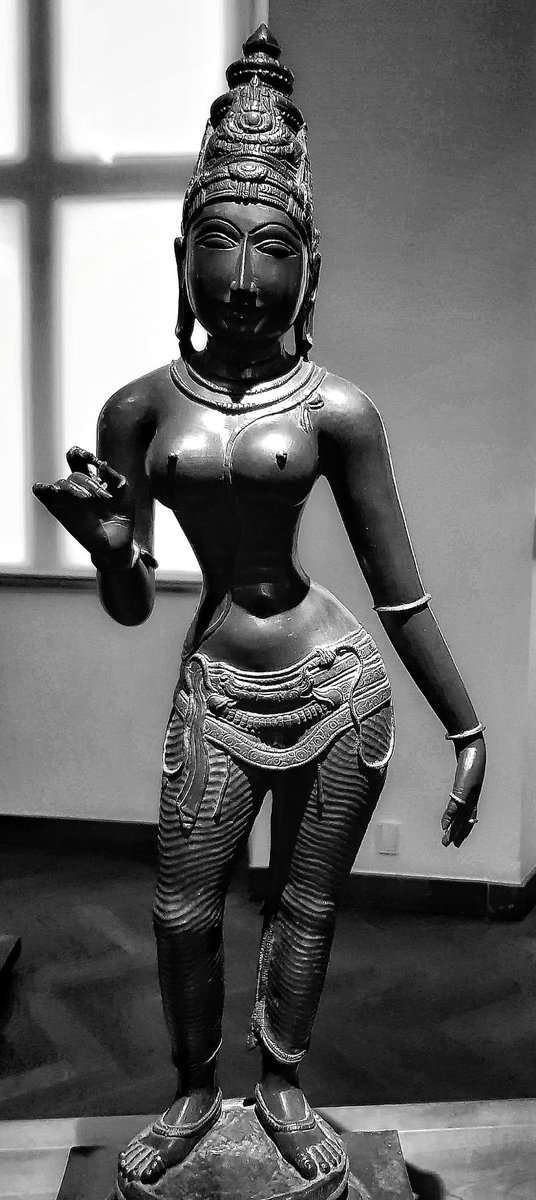

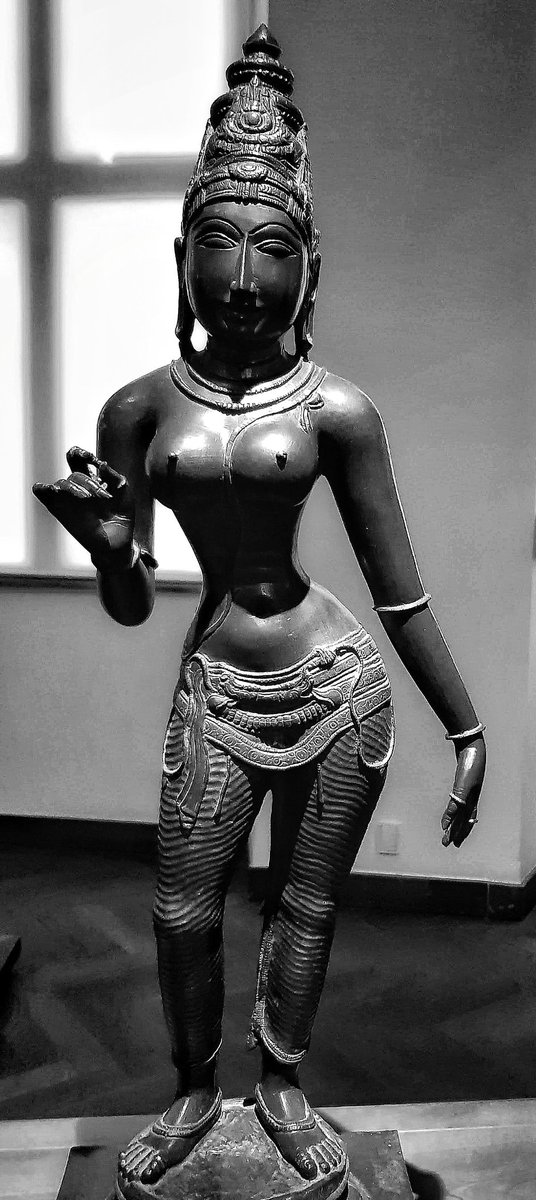

Exquisitely poised and supple, Chola bronze deities are some of the greatest works of art ever created in India. They stand silent on their plinths yet with their hands they speak gently to their devotees through the noiseless lingua franca of the mudras of south Indian dance.

For their devotees, their hands are raised in blessing and reassurance, promising boons and protection, and above all, marriage, fertility and fecundity, in return for the veneration that is so clearly their divine right.

It is the Nataraja, Shiva as Lord of the Dance, that is arguably the greatest artistic creation of the Chola dynasty. It is the perfect symbol of the way their sculptors managed to imbue their creations with both a raw sensual power and a profound theological complexity.

For the dancing figure of the god is not just a model of virile bodily perfection, but also an emblem of higher truths: on one level Shiva dances in triumph at his defeat of the demons of ignorance and darkness, and for the pleasure of his consort...

At another level- dreadlocks flying, haloed in fire- he is also dancing the world into extinction so as to bring it back into existence in order that it can be created and preserved anew.

With one hand he is shown holding fire, signifying destruction, while with the other he bangs the damaru drum, whose sound denotes creation. Renewed & purified, the Nataraja is dancing the universe from perdition to regeneration in a circular symbol of the nature of time itself

In Western art, few sculptors- except perhaps Donatello or Rodin- have achieved the pure essence of sensuality so spectacularly evoked by the Chola sculptors, or achieved such a sense of celebration of the divine beauty of the human body.

There is a startling clarity and purity about the way the near-naked bodies of the Gods and the saints are displayed, yet by the simplest of devices the sculptors highlight their spirit and powers, joys and pleasures, and their enjoyment of each other’s beauty.

In Chola sculpture the sexual nature of the Gods is strongly implied rather than directly stated. It is there in the extraordinary swinging rhythm of these eternally still figures, in their curving torsos and their slender arms.

The figures are never completely naked; these divine beings may embody desire, but unlike the sculpture at Khajaraho, Chola deities, while clearly preparing to enjoy bliss, are never actually shown in flagrante; their desire is frozen at a point before its final consummation.

For centuries there has been a tension in Hinduism between the ascetic and the sensual. In the sculptures of the Cauvery delta, this tension is partially resolved. More than in any other Indian artistic tradition, the Gods here are both intensely physical & physically gorgeous.

The sensuality of god was understood as an aspect of his formless perfection and divine inner beauty. Hence, in this tradition, the sensuous and the sacred are not opposed; they are one, and the sensuous is seen as an integral part of the sacred.

In this tradition it was not necessary to renounce the world, in the manner of the Jains or the Buddhists; nor was it necessary to perform the sacrifices of the Vedas. Instead, intensely loving bhakti devotion & pujas to images was believed to bring Salvation as effectively

For if the gods were universal, ranging through time & space, they were forcefully present in holy places & most especially in the idols of the great temples. Here the final climax of worship is still to have darshan: to see the beauty of the divine image, to meet the eyes of god

The gaze of the bronze deity meets the eyes of the worshipper, and it this exchange of vision—the seeing and the seen-- that acts as a focus for bhakti, the intense and passionate devotion of the devotee.

The gods created man,” said the sculptor Srikanda Stpathy, who still makes bronzes in Swamimallai “but here we are so blessed that we- simple men as we are- help create the gods.”

“When I see the worshippers praying to a god I helped bring into being, then my happiness is complete. I know that though the span of my life is only 90 years, the images live for a thousand years, & we live on in those images. We may be mortal, but our work is immortal”

(This text on Chola bronzes and the Stpathys of Swamimallai is taken from my 2009 book, Nine Lives. These photographs will all be on show @ArtVadehra in late May and @grosvenorart London in July)

Here is an early piece of mine on Chola bronzes, from 2006, reviewing Vidya Dehejia's fabulous RA show:

theguardian.com/artanddesign/2…

theguardian.com/artanddesign/2…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh