Yesterday, @jasonfurman tweeted out my NYT piece on the Biden infrastructure proposal. He claimed I had ignored the most obvious way to deal with any inflationary pressures that might arise—i.e. Fed rate hikes. 1/ nytimes.com/2021/04/07/opi…

I don’t share Jason’s view that fiscal policy can safely ignore inflation risk since the Fed can always handle any resulting inflation. Congress should not ignore inflation risk when contemplating a multi trillion-dollar spending package. That’s just irresponsible. 2/

I also don’t share the the view that the Fed can easily keep inflation in check via rate hates. I think it’s complicated and not settled science that rate hikes will temper inflationary pressures by dampening aggregate expenditures. 3/

There are other channels through which interest rates matter. And to the extent rate hikes can, in the extreme, cause deflation by engineering a domestic and/or international recession, we should be at least be weary of turning to them as a primary stabilizing tool. 4/

To be provocative, I asked Jason whether he had considered the possibility that Fed tightening might have perverse effects, raising rather than dampening inflationary pressures. It’s something I wrote about back in 2005, and I was curious to hear how he’d respond. 5/

He said, “No.” I suggested that it was worth considering and supplied a link. Unfortunately, the article I linked to didn’t include some of the relevant passages from an earlier version of the paper. 6/ levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp384.pdf

What I wanted to share was my own (co-authored) work, but I couldn’t find a link to the book chapter. I have it now. 7/ books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr…

I did not argue in that chapter (nor do I now) that rate hikes *will* lead to higher inflation. It’s an empirical question. We uncovered some interesting correlations, but that’s it. It deserves more rigorous study. 8/

Others have thought about this too. Tillmann, P. (2007) “Do interest rates drive inflation dynamics? An analysis of the cost channel of monetary transmission,” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. 9/ researchgate.net/publication/22…

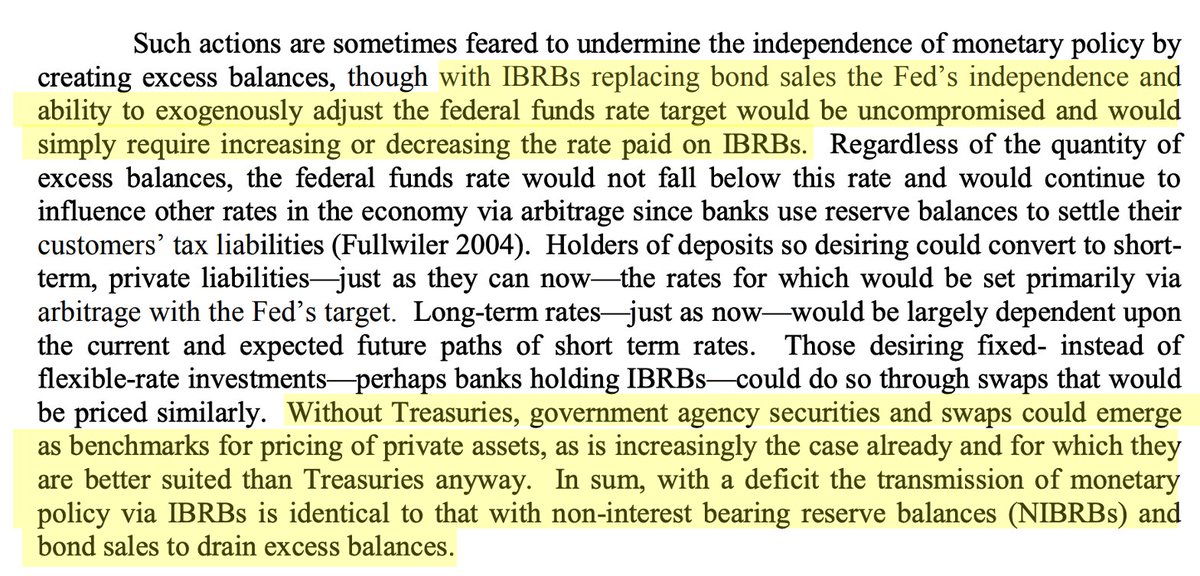

And here’s a series where Fullwiler (@stf18) draws on my 2005 paper to lay out the conditions under which monetary tightening *can* have perverse macro effects (i.e. stimulus vs cooling). 10/ neweconomicperspectives.org/2013/01/functi…

So here are my views…I consider interest-inflation dynamics an open and interesting question rather than settled (always negative sign) science. 11/

I think it's irresponsible to imply that Congress can safely ignore inflation risk when drafting a multi trillion-dollar spending package. 12/

I think it's naive to assume that the Fed can readily temper any inflation that might be fueled by substantial infrastructure spending. 13/

I think it makes sense to think hard about the offsets we are choosing, rather than grabbing any old “pay for” off the shelf for the purpose of satisfying the gatekeepers at the CBO. 14/

I think Congress should do its level best to mitigate inflation risk *preemptively* when drafting legislation, rather than ignoring inflation altogether and leaving it to the Fed to clean up any potential mess. 15/

Finally, saying that we should take inflation into account (ex ante) when *drafting* legislation (as MMT recommends) is not tantamount to saying that we have to use fiscal policy to fight (ex post) inflation. This is vital.

16/

16/

MMT does not tell us that we must use tax increases or spending cuts to fight inflation. We keep explaining this. neweconomicperspectives.org/2018/01/answer… and here ft.com/content/539618… . And the NYT column was all about using non-fiscal offsets to mange bottlenecks, etc. 17/

Although Jason and I appear to disagree about the purpose of a spending offset, as well as the best way to fight ex post inflation, we are having a more useful debate. 18/

I can remember when Jason was pushing $4T in deficit reduction when there was no inflation to speak of. I'm glad we're beyond that now. /end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh