This Day in Labor History: April 19, 1911. Furniture makers in Grand Rapids, Michigan went on strike to protest the terrible wages and working conditions that defined their lives. This is also a moment to talk about how religion can shape class consciousness!!

To begin with, that we are ever going to have a giant united class-based movement is a fantasy because everyone's going to bring such different life experiences into it. People aren't coming into class consciousness in a vacuum. Their whole lives influence their thoughts.

One of the real lessons of intersectionality is that we are all a creation of a series of interests and influences that overlap to create the person we are. This becomes quite clear if we look at the furniture workers strike and how religion was THE central issue here, not class.

By the late 19th century, Grand Rapids had become the center of the American furniture industry. With the region’s vast hardwood forests in close proximity, it’s hardly surprising that some upper Midwest town would center the furniture industry. I

It started to take off in the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 and grew rapidly from there. In 1890, the city had about 90,000 residents, of which about 1/3 were foreign born.

4,000 of these residents worked in the city’s 85 furniture factories. By 1910, the industry employed over 7,000 workers.

It was difficult for these workers to come together in a culture of solidarity. In a heavily immigrant community, one that was largely Polish, language barriers were a huge issue.

But Grand Rapids and the surrounding area were also a major home of Dutch Reformed churchgoers. This notoriously conservative Calvinist sect was not friendly to Catholics or to unions. That was a problem.

But there were attempts to organize workers, if not into unions per se, then into support organizations, going back to the 1880s. Still, there was little real move toward worker activism as the 1910s began.

Moreover, the Dutch and Poles had little in common, voting differently, having different positions on temperance and other social issues, and with different views on labor rights. In a city-wide ordinance to create an 8-hour day, the Poles voted for it, the Dutch against it.

But in 1909, one company fired a long-time worker, someone who had worked there for 26 years, when he led a committee of workers to the boss to ask for a raise. This had come out of the most skilled workers asking for a raise.

These were older immigrants, Swedes and Germans in part at least. The Poles occupied the lower stratum of the factories, whereas the Dutch tended to leave after a generation or two or weren’t as active in pressing for labor rights.

Anyway, that outrage really angered a lot of workers, even the Dutch Reformed.

The United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners provided the leadership here and hoped to bring these workers under their umbrella, much as the more skilled workers hoped to organize with that union. Over the next two years, the Carpenters raised demands again and again.

The main demand was a 10 percent raise. The companies tried to buy time.

The Carpenters agreed to delays, but after the furniture season of 1910 ended that summer (there was a big exhibit in July that was the annual peak of the industry), the companies said they would talk to individual workers.

But they also said that talking to a union was a restriction of their freedom and they would not negotiate a contract

The Carpenters did not rush into strikes. They took the earlier rejection in stride and then came back in January 1911 with additional demands.

Again, the 10 percent pay raise, but also a reduction in working hours from 10 to 9 with no pay reduction, a minimum wage to replace piecework, and collective bargaining.

The mayor, sympathetic to the workers, attempted to arbitrate a solution. The furniture makers blew them both off and the strike was on in April.

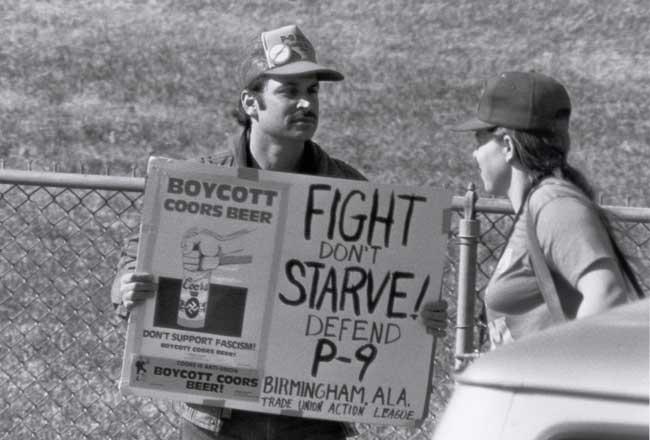

The employers were as intransigent as any others during this anti-union era. They refused to negotiate with the workers or the UBC. They put pressure on bankers to foreclose on strikers’ homes. This was hard on the strikers. Workers were poor.

The Carpenters did not have a large strike fund. Many workers had to rely on their churches to get by, some of whom were both strained and not supportive. It did not help when the furniture makers started bringing the scabs.

The Carpenters worked hard to keep the strikers from engaging in violence against them, as the union knew that would lead to nothing positive.

But the bishop in Grand Rapids did support the strikers and with so many Catholic immigrants in town, that mattered a lot. More surprisingly, the mayor remained on their side, angering the employers.

There was a lot of fear of the scabs bringing smallpox into the city and the mayor acted to restrict them. A judge ruled in favor of workers’ right to picket.

The Dutch, nervous about all of this, restricted themselves to picketing. The Poles were happy to throw rocks and break windows. Moreover, it was their wives who led the militancy, often throwing rocks into the back of the heads of strikebreakers who were walking by.

The furniture companies called in the Pinkertons, but the mayor allowed the strikers to arm themselves with sticks and form militia-like structures in defense.

Violence became more common by mid-May, with a May 15 action that led to a mass rock-throwing incident by the Poles that even the mayor couldn’t stop.

In the aftermath, the Carpenters’ lead organizer in Grand Rapids, William MacFarlane, started tipping off the police when he feared violence.

What broke the strike after four months was the Dutch Reformed ministers, who basically ordered their parishioners back to the job. They said that union membership was incompatible with church membership.

Both the Dutch and the UBC were not comfortable with the militancy of the Poles either. This forced a deal, but workers got little more than the 9-hour day. The Poles stayed out a little longer but without Carpenters’ support, they had no chance for a better deal.

In the aftermath, the furniture makers weakened the position of the city’s mayor so they would never have to deal with political opposition from someone who mattered again. Moreover, no long-standing labor movement came out of what ended up as an isolated incident.

It would take until 1937 and the rise of the CIO that Grand Rapids furniture workers would be first organized with the United Auto Workers.

Today, the Dutch Reformed influence is still very strong in this region, which is bought and owned by the DeVos family, based in Grand Rapids. This was also Justin Amash’s congressional district until recently, so, yeah, this is a special place.

In conclusion, we can pretend like we can someday unite all workers based around class. Or we can come honestly to them and realize that there are going to be huge challenges in uniting workers, very much including religion.

I know we like our myths and ideology in the labor movement but fantasies don't help.

I borrowed from Mary Patrice Erdmans, “The Poles, the Dutch, and the Grand Rapids Furniture Strike of 1911,” published in the Autumn 2005 issue of Polish American Studies for many of the details of this not well-known labor action.

Back tomorrow for a brand new thread to discuss Native and Filipino workers uniting in the Alaska fish canneries.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh