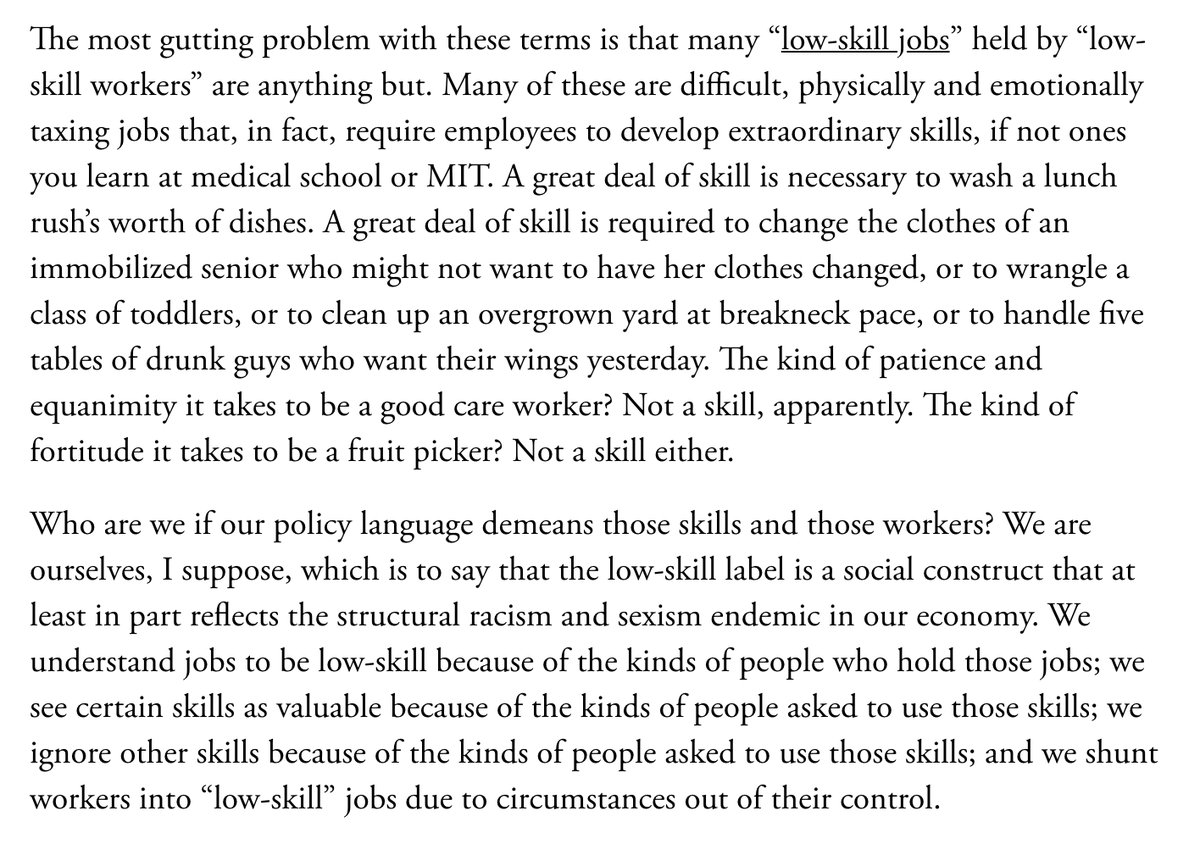

I love this @AnnieLowrey jeremiad against the term "low-skill jobs." Those jobs aren't low-skill. They're low-wage, and calling them low-skill is a way of blaming often exploited workers for inequality and unemployment. theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/…

The idea that a 23-year-old at McKinsey is a high-skill worker while a home healthcare aide with 30 years of experience is low-skill is risible.

The latter may be paid more, but they're not more skilled. And the language of skills recasts that pay gap as natural, even virtuous.

The latter may be paid more, but they're not more skilled. And the language of skills recasts that pay gap as natural, even virtuous.

As Annie writes, the point isn't that we shouldn't learn different skills as the economy changes. The point is the language of low and high-skilled jobs obscures the realities of power and policy operating behind this debate.

I've covered endless rounds of the "skills" debate, which particularly pops up in the aftermath of recessions, when people want to explain high unemployment as more than a failure of fiscal and monetary and labor policy.

So I'm sure I've used skills language before. But I won't from here on out.

Annie's right: "All jobs could be good jobs. But only policy makers and business leaders have the skills to make that happen, not workers."

Annie's right: "All jobs could be good jobs. But only policy makers and business leaders have the skills to make that happen, not workers."

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh