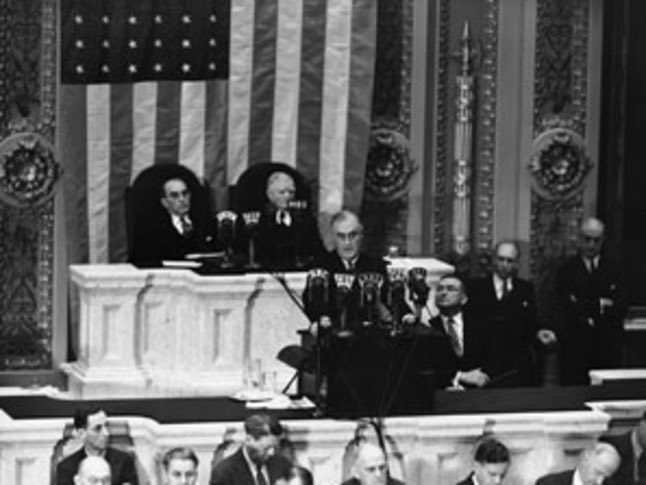

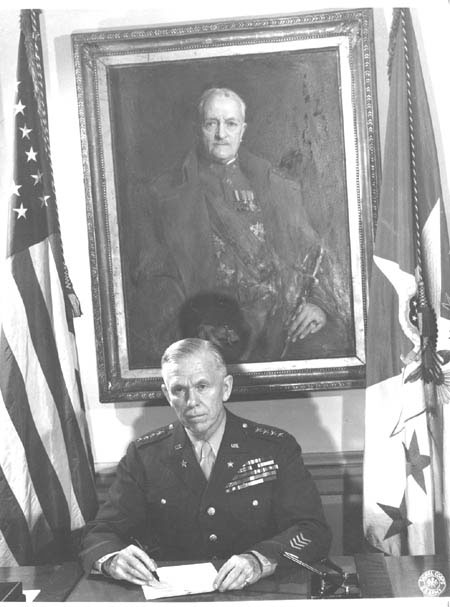

While serving as Chief of Staff from 1939 to 1945, on several occasions GEN George C. Marshall would press for two major US Army advancements. The first is more prolonged and systematic training than the Army had ever seen before.

Every soldier would be trained well, as an individual, and then trained in small units, and as members of divisions, ultimately tested in field maneuvers.

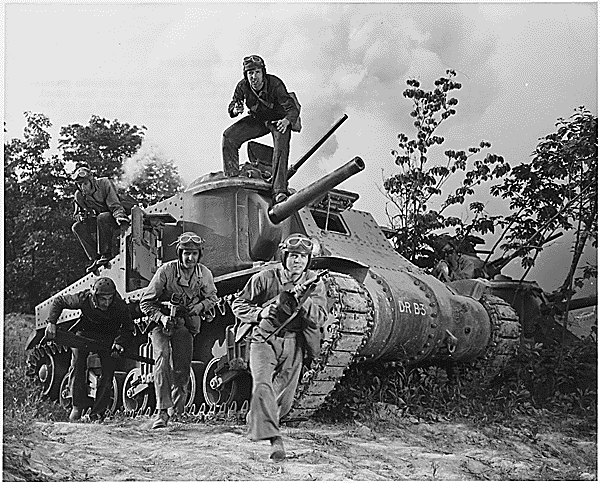

The other advancement was for intensive coordination of multifaceted effort, also on a level the @USArmy had never really seen before – Combined Arms.

This would include the development of teamwork between Infantry, Armor, Artillery, and Engineers – this had long been a guideline for training but never a fully realized achievement. @JimRainey10 @usacac @usacactraining @USArmyDoctrine @ShaneMorgan_WF6 @USArmy_CALL @USArmyMCCoE

This second advancement also included coordination between Army ground and air forces, which had been demonstrated by the Germans but at which we would eventually excel.

There was also coordination between the @USArmy ground and air forces and the @USNavy which would make amphibious operations possible. This emphasis on coordination proved beneficial when the Army eventually entered WWII and fought in different theaters of war around the world.

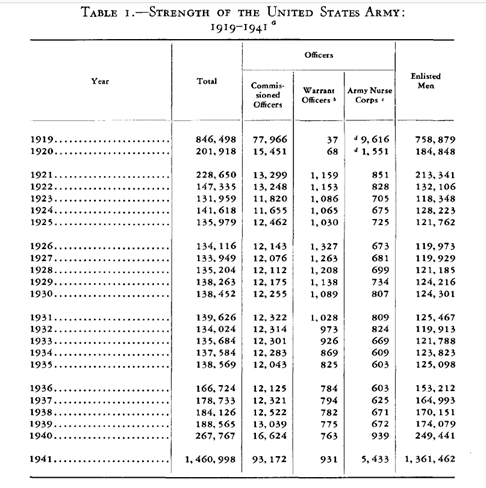

But before we could get to that incredible progress in training, we needed an Army to train. From the end of WWI, for a period of about 15 years, the US Army saw an almost continuous weakening in manpower (numbers).

During the first month of “demobilization” following the end of WWI, the US Army released over 600,000 soldiers and officers, and within the first 9 months of “demobilization” about 3¼-million were released, and this was somehow done without any major impact to the US economy.

At the same time, the country was “demobilizing” the war industry that had been converted and built up to support WWI production, as well as disposing of surplus materials. The War Department maintained a reserve of weapons and materiel, however, for emergency use.

There was no real plan for demobilization following WWI, and the Army had a new problem to go along with this process: they lacked the authority to enlist new soldiers. But in early 1919, Congress approved Regular Army enlistments for periods of 1-3 years.

During this 15-year period following WWI, the bulk of the Interwar Years, the Army also saw the steady degradation and obsolescence of equipment.

The general consensus was that the equipment we had should be used up rather than replaced. This was basically the government saying, “play with the toys you have, you don’t need more.”

This chart shows what happened to the Army during the Interwar Years and the breakdown of Officers to Enlisted:

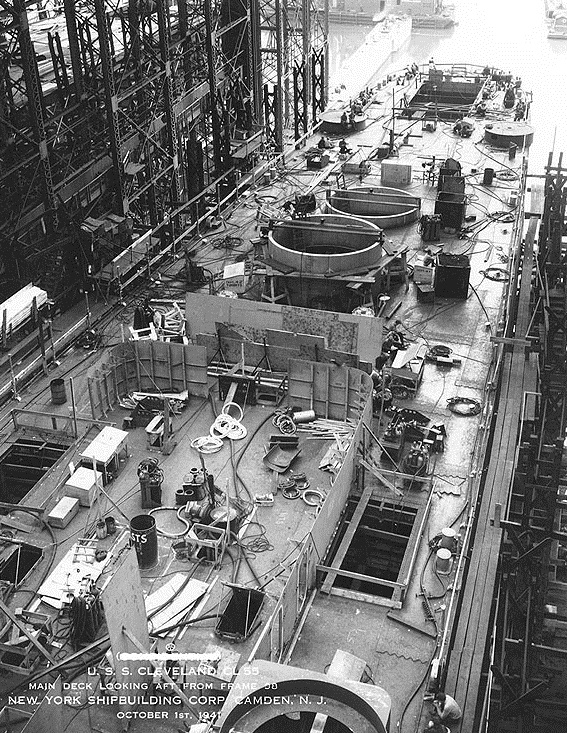

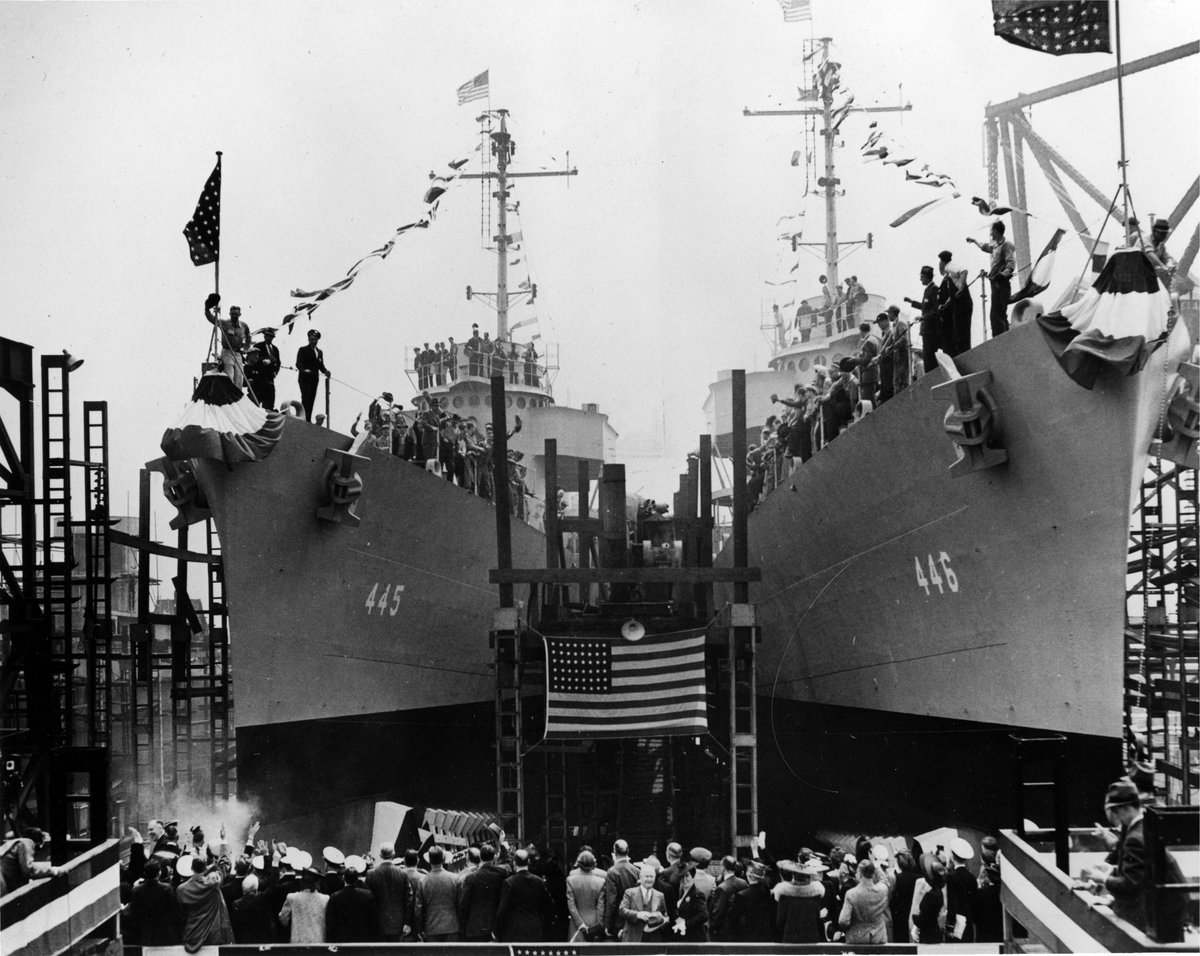

Around the mid-1930s, the @USNavy was granted permission to start a new shipbuilding program. This was, of course, with only very careful spending allowed because of the Great Depression. The program was aimed at creating jobs.

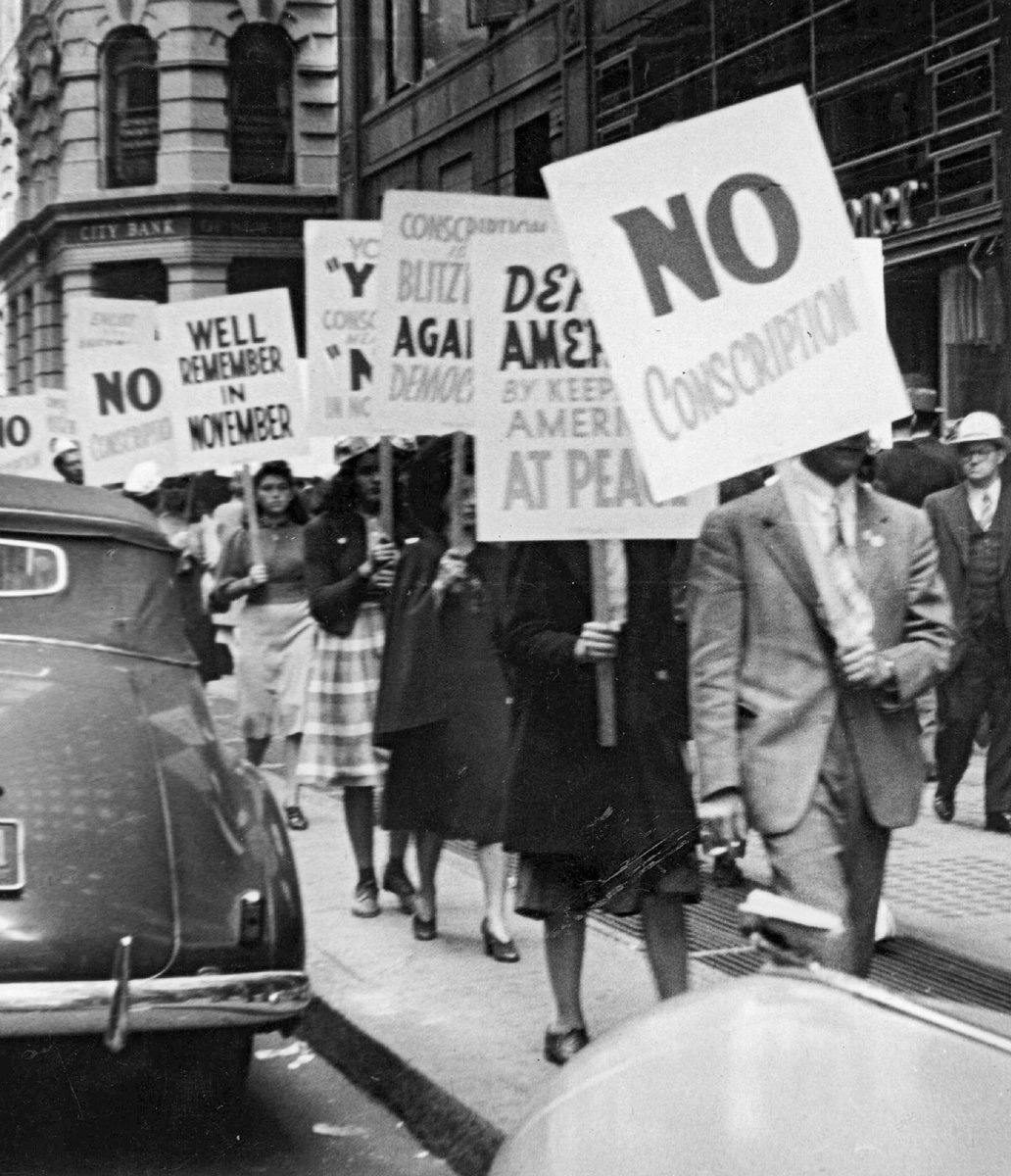

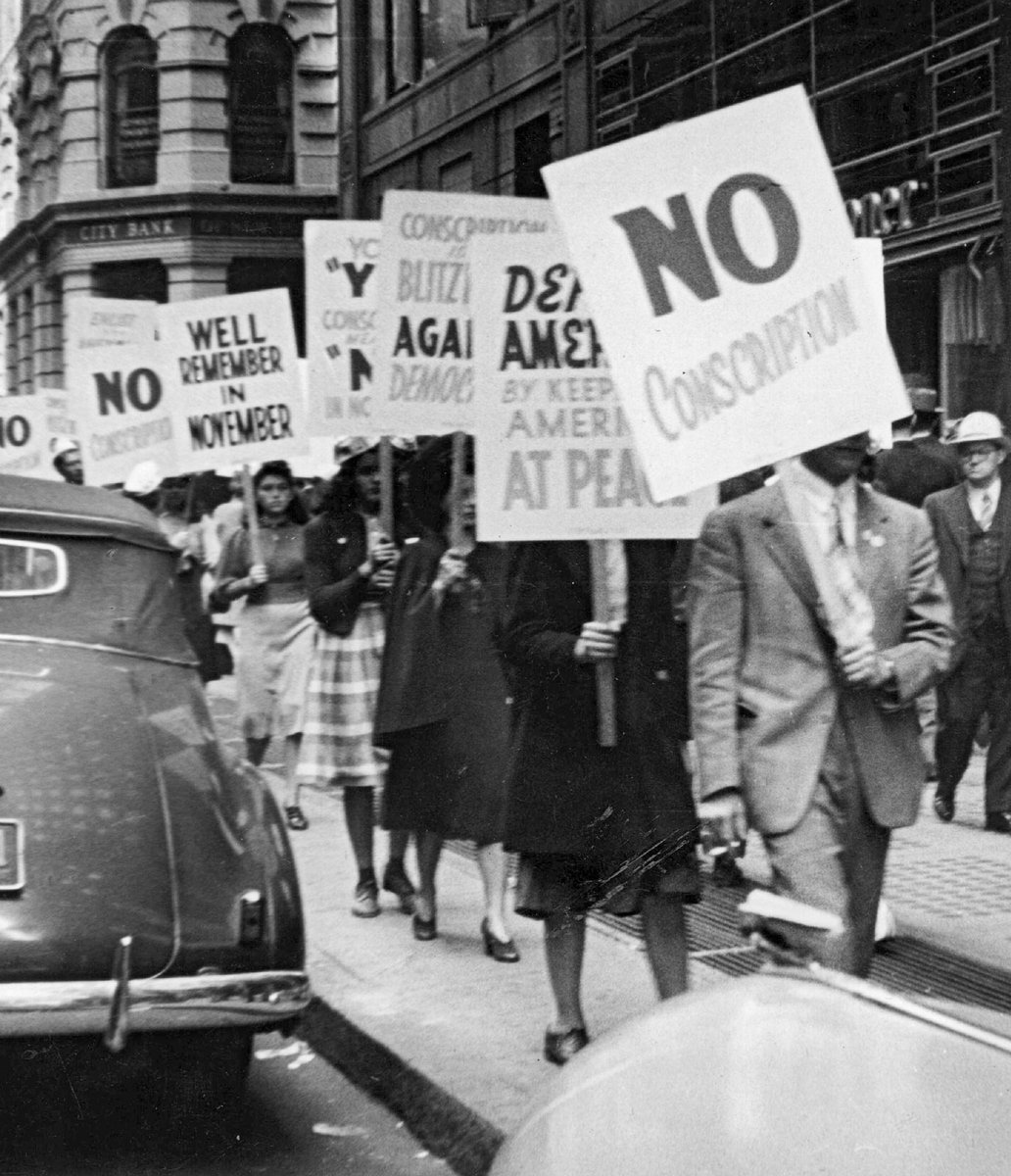

The Army received less love at this time. The American public was still put off by anything “military” after the experience of WWI, and the Great Depression made it hard to care about something most people didn’t think we would need to use again.

Facing the struggles of significantly lower funding, fewer options to push for new equipment, and the National Defense Act of 1920 basically saying we don’t need an expandable Army, we can fill the need with citizen soldiers through the Reserve Corps and National Guard –

– the Regular Army did what it could to focus “its limited resources on maintaining personnel strength rather than on procuring new equipment.”

In other words, there was less waste and lower consumption of scarce resources during this time because the focus was on maintaining the smaller force that the Army had, rather than procuring new equipment.

During WWI, the @USNationalGuard had been absorbed into the @USArmy which basically left the individual states without Guard units after the end of WWI. The National Defense Act of 1920 provided the Guard be around 436,000 but in reality this balanced out around 180,000.

Though smaller than planned, this Guard force was essential as it took over any domestic responsibilities that the Regular Army would have otherwise had to manage without a National Guard force available.

About 1/10th of the overall War Department budget went to supporting the @USNationalGuard during the Interwar Years. The War Department also provided “training officers and large quantities of surplus World War I materiel”.

Although not on the same level as the Regular Army as far as readiness goes, “by 1939 the increasingly federalized Guard was better trained than it had been when mobilized for duty on the Mexican border in 1916.”

Prior to WWI, the Regular Army provided equipment and about 100 officers per year to support college ROTC programs. But before the National Defense Acts of 1916 and 1920, the ROTC program was only loosely focused on Army needs.

With the National Defense Act of 1920, the Regular Army would now depend on the @USNationalGuard and @USArmyReserve for expansion, and the Officers’ Reserve Corps would serve as “a vehicle to retain college men in the Army... after graduation.”

This allowed the expansion of ROTC programs after 1920, and “by 1928 there were ROTC units in 325 schools enrolling 85,000 college and university students.” @ArmyROTC @CG_ArmyROTC

“Officers detailed as professors of military science instructed these units, and about 6,000 graduates were commissioned in the Officer Reserve Corps each year. Thousands of other college graduates received at least some military training through the inexpensive program.”

This paid off in 1940 and 1941 when the United States began mobilizing in order to meet the growing threat of war. (This pic is actually JROTC in a parade in April 1941.)

From 1921 until 1936, the general premise of American policies regarding potential future wars with major world powers was that they could almost all be avoided. Japan was a possible exception.

By pursuing the goal of maintaining only minimum defensive military strength, the US basically hoped to make this wishful thinking of no more involvement in world wars a reality.

There was a general consensus in the Army, however, that the government and American public “in their antipathy to war failed to support even the minimum needs for national defense.”

With massive oceans on both sides, there was a sense of confidence throughout the country, shared by those in Congress and even the White House, that the @USNavy could be the nation’s first line of defense and potentially the only necessary line of defense.

Not everyone wanted to prepare for the worst and hope for the best. “The abiding need for trained and equipped ground forces, recognized and continuously recalculated by the Army’s General Staff, was generally ignored by the ultimate authority in government.”

We focus more on the European Theater in this series regarding developments of WWII, but in 1931 the Japanese seized Manchuria and pushed back against League of Nations and American efforts to end the occupation. Instead, Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933.

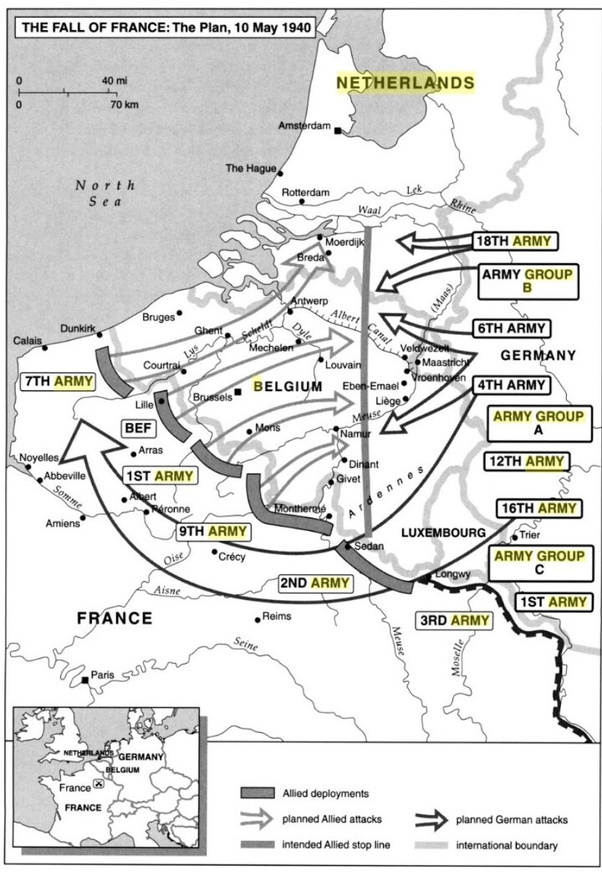

Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, almost immediately denounced the Treaty of Versailles, which had ended WWI, and he directed the nation to begin rearming. By 1936, the Germans had reclaimed the demilitarized zone in the Rhineland.

Italy, under Mussolini, attacked Ethiopia in 1935 and the Spanish Revolution of 1936 led to a third European dictatorship and a civil war that would ultimately become “a proving ground for weapons and tactics used later in World War II.”

By 1937, Japan was invading China. In early 1938, Germany annexed Austria and later that year moved against Czechoslovakia. By 1939, Germany had seized Czechoslovakia and war in Europe was on the horizon.

Congress responded with a series of neutrality acts passed between 1935 and 1937, with the aim of avoiding American involvement in another European war. As a nation, we did a lot to try to stay out of it for as long as we could.

The US also sought diplomatic strength through improving relations with the Soviet Union (1933) and the Philippines (1934) and a “good neighbor” policy approach with Latin America.

It wasn’t until 1935 that larger US military appropriations would start getting approved, supporting efforts (little by little) to improve military readiness.

Many of the changes we saw in the US Army from 1935 to 1938 were largely due to careful planning within the War Department during the time that General Douglas MacArthur served as the Chief of Staff.

This includes the reorganization of combat forces and more realistic planning for the use of manpower and the “industrial might of the United States for war if it should become necessary.”

One of MacArthur’s goals as Chief of Staff was to improve “strategic mobility” – “using the Army’s limited resources to replace horses as a means of transportation and to create a small, hard-hitting force ready for emergency use.”

There was a need for new organizations within the Army that could better control the training of large ground forces, as well as air forces and combined arms units, and to train the command of all these forces in preparation for possible war.

By 1935, the War Department had created 4 army headquarters and a headquarters for the air forces in an effort to meet these training needs.

Starting in the summer of 1935, the Regular @USArmy and the @USNationalGuard were authorized to begin training together in exercises, including joint exercises with the @USNavy. Congress also authorized increasing the Active-Duty force to 165,000.

When money allowed, the Army would equip and train combat forces for mobile operations – which were quite different from the static warfare experienced in WWI on the Western Front. So progress was being made, but we could only afford to progress so fast.

By 1938, the US Army was at a greater strength than it had been in the years prior, and with an improved state of readiness. But the recent increases to numbers and readiness of foreign armies had grown more and even faster than our own.

There's a lot more to come on this topic!

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can still catch up! You can find all of the threads saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link twitter.com/i/events/13642…

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can still catch up! You can find all of the threads saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link twitter.com/i/events/13642…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh