Seventh in my series on Hafsa bint Sirin. I pause in my story of Hafsa's life to consider classical storytelling about her life and its intents, specifically motherhood, before the final thread next week where I share what I think her social life was really like.

Earlier threads detailed how the sources tend to paint pious women as recluses. The message over time is that good women restrict their social lives, especially their public social lives, even if that means restricting spiritual or scholarly engagement.

https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1378725474420002817?s=20

But what I have been arguing over this series of threads is that pious and Sufi women lives were not restricted in the way they are portrayed.

https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1368609115837243396?s=20

Despite messaging that silence is purity, there is little historical ground for it. If we take the examples Prophet’s family and early pious and Sufi women seriously, then there is no “sunna” of silence or social disengagement to be a good woman.

https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1371113642582757380?s=20

Consider that the portrayal of the tender relationship between Hafsa and her son is out of character in most accounts of early pious and Sufi women.

For more detail on these stories see my piece, "Early Pious Mystic and Sufi Women" linked here. llsilvers.com/nonfiction

For more detail on these stories see my piece, "Early Pious Mystic and Sufi Women" linked here. llsilvers.com/nonfiction

When children are mentioned in these sources, it is almost always in bare sketches depicting their service to their mothers, transmitting their mother’s wisdom, or, less often, distracting their mothers from their worship.

For all the idealization of mothers in Islam from the early period onward, it is surprising to find this aspect of women’s experience missing from biographies devoted to articulating their piety.

Even in those very few accounts in which a loving relationship is depicted between mother and child, like Hafsa and al-Hudhayl, the stories seem to be used mainly to portray the mother as an idealized solitary worshipper, not an idealized mother.

After al-Hudhayl died, Hafsa became close with her student Hisham who seems to have become something of an adopted son to her. She shared stories about al-Hudhayl with him which he transmits and are recorded in the sources.

While we can imagine the real life scene of Hafsa sharing her grief and stories of her son’s devotion with Hisham, the student who stepped into that gap in her life, the transmitters are sharing them for their own purposes.

Najam Haider @nhaider74 calls this kind of historical storytelling “rhetoricizing,” in which historians, biographers, and transmitters took stories--often well-known to their audience--and reframed them to make a point. ajammc.com/2020/10/12/aja…

Recall that Sulami and Ibn al-Jawzi tell her story to different ends. Sulami disembodies her, turning her into a luminous soul to vouch for her sanctity, while Ibn al-Jawzi gives small details of her life to diminish her scholarly authority.

https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1381275176629854208?s=20

Ibn al-Jawzi’s framing of the story of the tenderness of her relationship with her son and Hisham was both to diminish her authority and argue that the exemplars of womanhood stay awake all night in solitary prayer and fast every day. So should you.

https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1381275157105364997?s=20

Again, in most accounts of mothers in early pious and Sufi women, with some exceptions, the stories seem to be used to portray the mother as an idealized solitary worshipper, not an idealized mother. Ibn al-Jawzi was the same.

(Anyone interested in the notions of motherhood past and present in Islam should check out the work of Irene Oh and Avner Giladi. I’ll link to Giladi’s work here since it is all historical detail about this period.) scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&…

So playing down the presence of children in these women’s lives seems to have less to do with deemphasizing the women’s identity as mothers or grandmothers as it does with de-emphasizing women as embodied social beings of which motherhood is a part.

While the previous threads have mainly been about the efforts of transmitters to tell Hafsa bint Sirin’s life to their own ends, next time I’ll complete this series by sharing what social history can say about the lives of early Muslim women and the take away for Hafsa’s life.

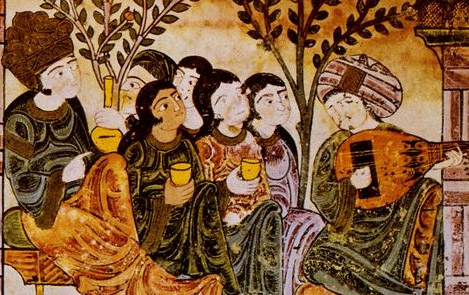

Hint: She had a busy social life to the point that we have to ask, when was this supposedly solitary woman ever alone? (Okay, she was not like these highly elite women who are listening to music with cups of who knows what in their hands, but she had a very busy social life.)

As always, if you like the way I think about history, you may like my novels, The Sufi Mysteries Quartet. These kinds of observations about women in history are woven into an emotionally riveting whodunit set in Baghdad in Abbasid days. 💚

https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1378004836629745667?s=20

Links to get my historical mystery series on all e-book platforms and paperbacks online are available on the front page of my website. The academic editions are also available on order from your local bookstore. To be read in order, start with The Lover!

llsilvers.com

llsilvers.com

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh