There are certainly a lot of anecdotal reports right now of employers not being able to find the workers they need, particularly in restaurants. But unemployment is still very elevated—particularly among restaurant workers. What’s going on? 1/

First, remember there is *always* a chorus of employers who claim they can’t find the employees they need. One reason for that is that in a system as large and complex as the U.S. labor market there will always be pockets of bona fide labor shortages at any given time. 2/

But a more common reason is employers simply not wanting to raise wages high enough to attract workers. Employers post their too-low wages, can’t find workers to fill jobs at that pay level, and claim they’re facing a labor shortage. 3/

Given how pervasive this dynamic is, I often suggest that whenever anyone says, “I can’t find the workers I need,” you should add “at the wages I want to pay.” 4/

Further, a job opening when the labor market is weak doesn’t necessarily mean the same thing as a job opening when the labor market is strong. There is a wide range of “recruitment intensity” that an employer can apply to an open position. 5/

If employers are trying hard to fill an opening, they will increase the pay and perhaps scale back the required qualifications. If they’re not trying very hard, they’ll offer low pay and hike up the required qualifications. 6/

Recruitment intensity is cyclical, so when a job opening goes unfilled when unemployment is elevated like it is today, employers are even more likely than normal to be holding out for an overly qualified candidate at a very cheap price. 7/

The footprint of a bona fide labor shortage is *rising wages*. Employers who truly face shortages of workers will respond by bidding up wages to attract those workers, and employers whose workers are being poached will raise wages to retain their workers, and so on. 8/

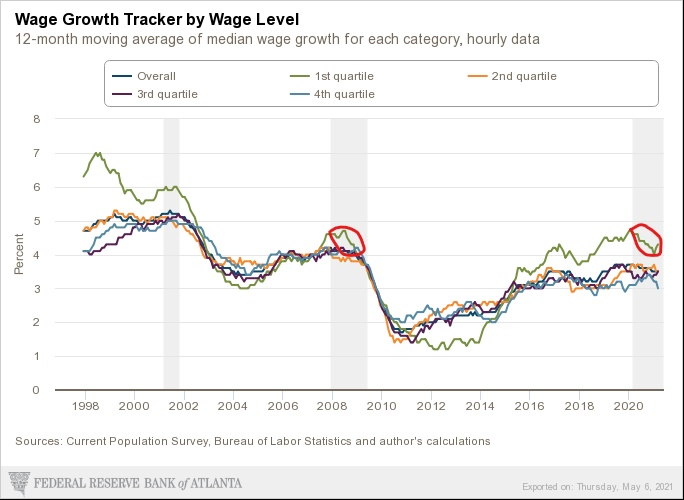

When you don’t see wages growing to reflect that dynamic, you can be fairly certain that labor shortages, though possibly happening in some places, are not a driving feature of the labor market. And right now, wages are not growing at a rapid pace. 9/

While there are issues with measuring wage growth due to “composition effects” in the pandemic, wage series that account for these issues are not showing an unusually strong increase in wage growth. 10/ whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/…

At a recent press conference, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell dismissed anecdotal claims of labor market shortages, saying, “We don’t see wages moving up yet. And presumably we would see that in a really tight labor market.” 11/

Also, when restaurant owners can't find workers to fill openings at wages that aren’t meaningfully higher than they were before the pandemic—even though the jobs are harder b/c workers now have to deal with anti-maskers and health concerns—that's not a labor shortage. 12/

Further, the labor market added 280,000 jobs in the leisure and hospitality sector in March, the sixth highest percent increase in the last half century, even though average weekly earnings for nonsupervisory workers in that sector equate to annual earnings of just $19,651. 13/

And, while there are certainly fewer job seekers than there would be without COVID—many people are out of the labor market because of Covid-related care responsibilities or health concerns—there are far from enough job openings to provide work for all job seekers. 14/

In the latest data on job openings, there were nearly 40% more unemployment workers than job openings—and more than 80% more unemployed workers than job openings in the leisure and hospitality sector. 15/

One question people raise is whether expanded pandemic unemployment benefits are keeping workers from taking jobs. There was also a lot of fuss about this question a year ago, when workers were getting a $600 additional weekly benefit. 16/

There were several rigorous papers that looked at the impact of the $600, and found extremely limited labor supply effects. If the $600 a week wasn’t keeping people from taking jobs then, it’s hard to imagine that a benefit *half* that large is having that effect now. 17/

Here are those papers: nber.org/papers/w28470, tobin.yale.edu/sites/default/…, marinescu.eu/publication/ma…

Recent history is helpful here. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, counterintuitive reports about employers not being able to find the workers they need captured the public’s imagination over and over again. And (surprise!) it’s happening again here. 19/

After the Great Recession, people claimed there were worker shortages b/c workers didn’t have the right skills for available jobs. We now know that was totally wrong. We got to a 3.5% unemp rate without a massive national training program that accelerated skills attainment. 20/

Thankfully, the “workers don’t have the right skills!” claims have been mostly quiet this time around. But alas, the claims of worker shortages are still deafening. Just remember that like last time, there is likely a LOT less to this than meets the eye. 21/

Aaaand here’s all this in op-ed form. 22/

https://twitter.com/JosephEStiglitz/status/1389556777709092871?s=20@AndreaGurwitt

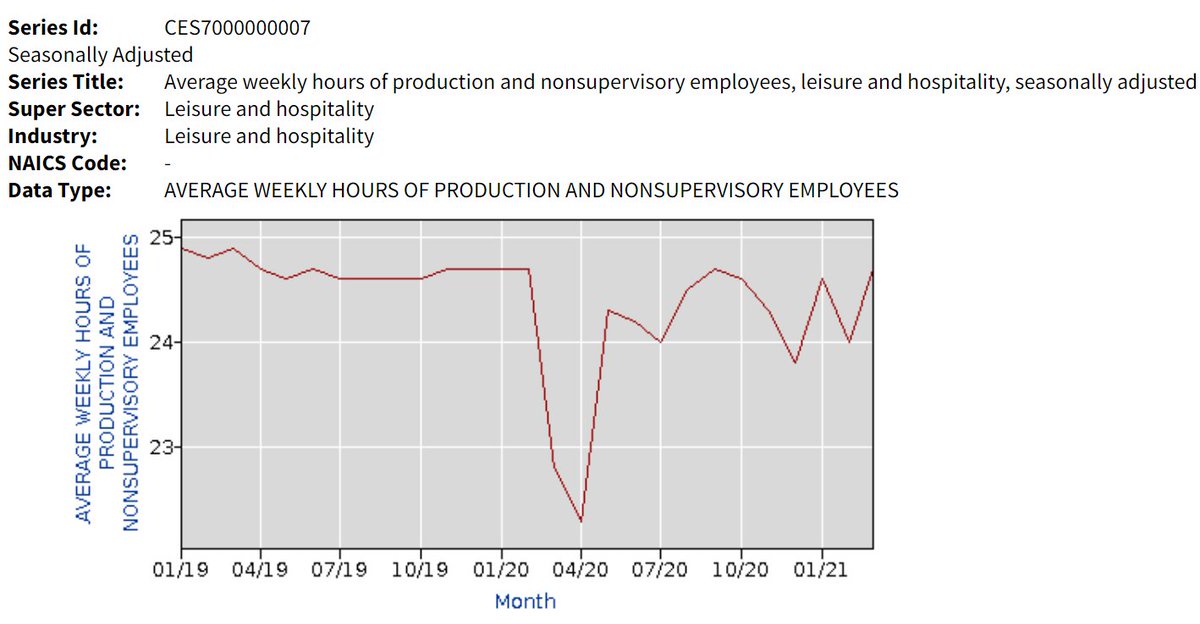

Excellent additional point here. If employers really couldn't find the workers they need, you'd expect them to be ramping up the hours of the workers they have... 23/

https://twitter.com/joshbivens_DC/status/1389579071936413708?s=20

Another key point—tips are down in restaurants, so restaurants must pay higher base wages for workers to get their pre-COVID earnings. This survey found that more than 2/3rds of restaurant workers report tips have dropped at least 50% since COVID. 24/ onefairwage.site/wp-content/upl…

Note, some people are saying that because wages at the low end of the labor market haven’t dropped as much in this recession as they did in the great recession, we have a labor shortage now. So much about that is wrong! 25/

For one, in the first 13 months of both recessions, wage growth for the bottom quartile dropped by about half a percentage point on net. 26/

And of course, if there were a shortage, we'd expect wage growth to be *rising*, not just not falling. 27/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh