1/5

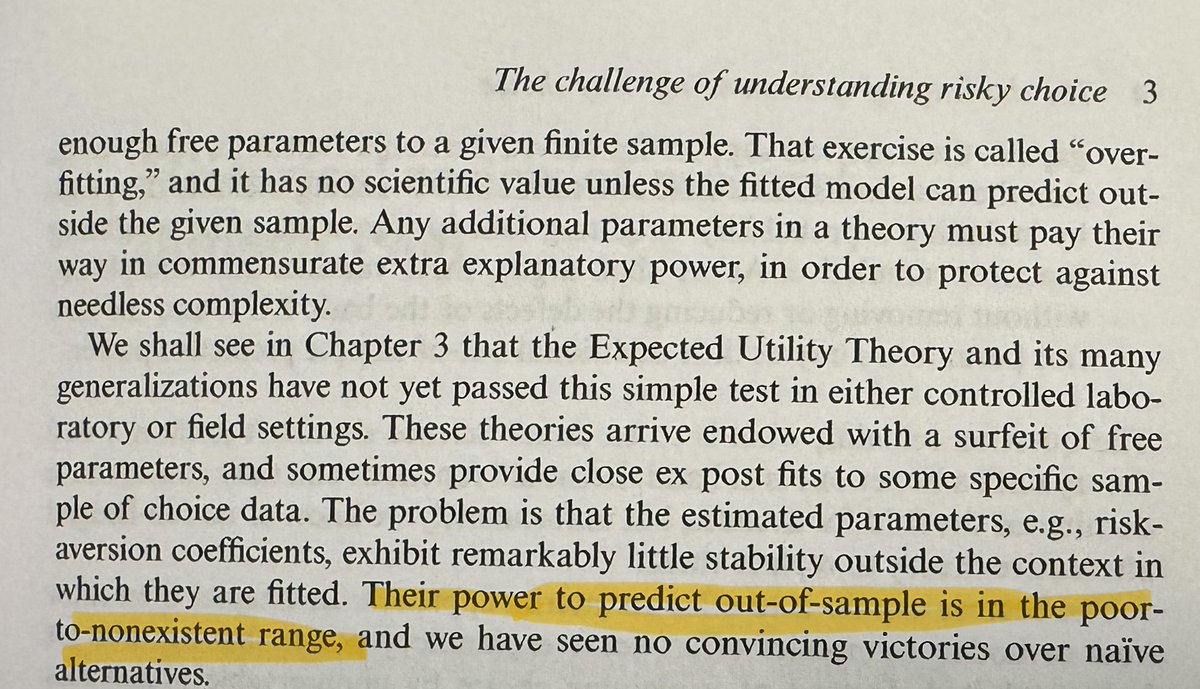

The Copenhagen experiment showed that Ergodicity Economics (EE), limited to its predicted utility functions for given dynamical settings, is a better fit to human behavior than classic expected-utility theory with a freely chosen single utility function.

The Copenhagen experiment showed that Ergodicity Economics (EE), limited to its predicted utility functions for given dynamical settings, is a better fit to human behavior than classic expected-utility theory with a freely chosen single utility function.

2/5

I don’t find this terribly interesting. Classic expected-utility theory is conceptually flawed, and science is more than data-fitting. However well or poorly it fits observations, one would have to reject expected-utility theory anyway.

I don’t find this terribly interesting. Classic expected-utility theory is conceptually flawed, and science is more than data-fitting. However well or poorly it fits observations, one would have to reject expected-utility theory anyway.

3/5

Here is what's interesting: I didn’t think EE would perform well in the Copenhagen experiment because I had bought into the narrative that the tested behavior was shaped by evolution over millions of years and cannot be re-learned on short time scales.

Here is what's interesting: I didn’t think EE would perform well in the Copenhagen experiment because I had bought into the narrative that the tested behavior was shaped by evolution over millions of years and cannot be re-learned on short time scales.

4/5

The experiment finds something else: we’re astonishingly quick at adapting to new dynamic environments. This opens the door to a whole new way of thinking about how and what we can learn. The brain is far more plastic than economic models suggest.

The experiment finds something else: we’re astonishingly quick at adapting to new dynamic environments. This opens the door to a whole new way of thinking about how and what we can learn. The brain is far more plastic than economic models suggest.

5/5

The really exciting bit: economic decision models are widely used in neuroscience. If we can improve on these models, it can have a direct effect on neuroscience.

Hence my enthusiasm for our collaboration with @DRCMR_MRI.

The really exciting bit: economic decision models are widely used in neuroscience. If we can improve on these models, it can have a direct effect on neuroscience.

Hence my enthusiasm for our collaboration with @DRCMR_MRI.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh