Hello, it’s a gorgeous Thursday! Time for a #DBIOtweetorial by Eleni Katifori, commissioned by the awesome folks at #engageDBIO! Let's get sciencing!

Large organisms cannot survive without a circulatory system. Diffusion is too slow to provide enough nutrients. For this reason, plants, animals and fungi have evolved complex irrigation systems.

Circulatory systems roughly follow some simple design principles. They are composed of wide vessels, “highways” for long distance transport, and smaller, distributary channels, which do the actual delivery of the load. Similar function can result in similar design!

Flow networks in biology can be approximated by resistor networks, like the ones we learn in Physics 101. The voltage is like the pressure, the electric current is like a fluidic current, and the electric resistance is the fluidic resistance, as derived by Poisseuille’ law.

The resistor models are quite successful! However, to model real networks, we need more. We need to store fluid (capacitors), to account for inertia (inductors), to use valves (diodes), and to consider other nonlinearities.

With capacitors and inductors, we can have a propagating energy pulse like in transmission lines. The amplitude of the pulse is attenuated as it moves, like our own pulse that disappears by the time it reaches the capillaries.

Biological flow networks are under huge evolutionary pressure to perform efficiently their tasks, while keeping building costs low. Murray’s law predicts the scaling law by minimizing the energy loss due to viscous forces.

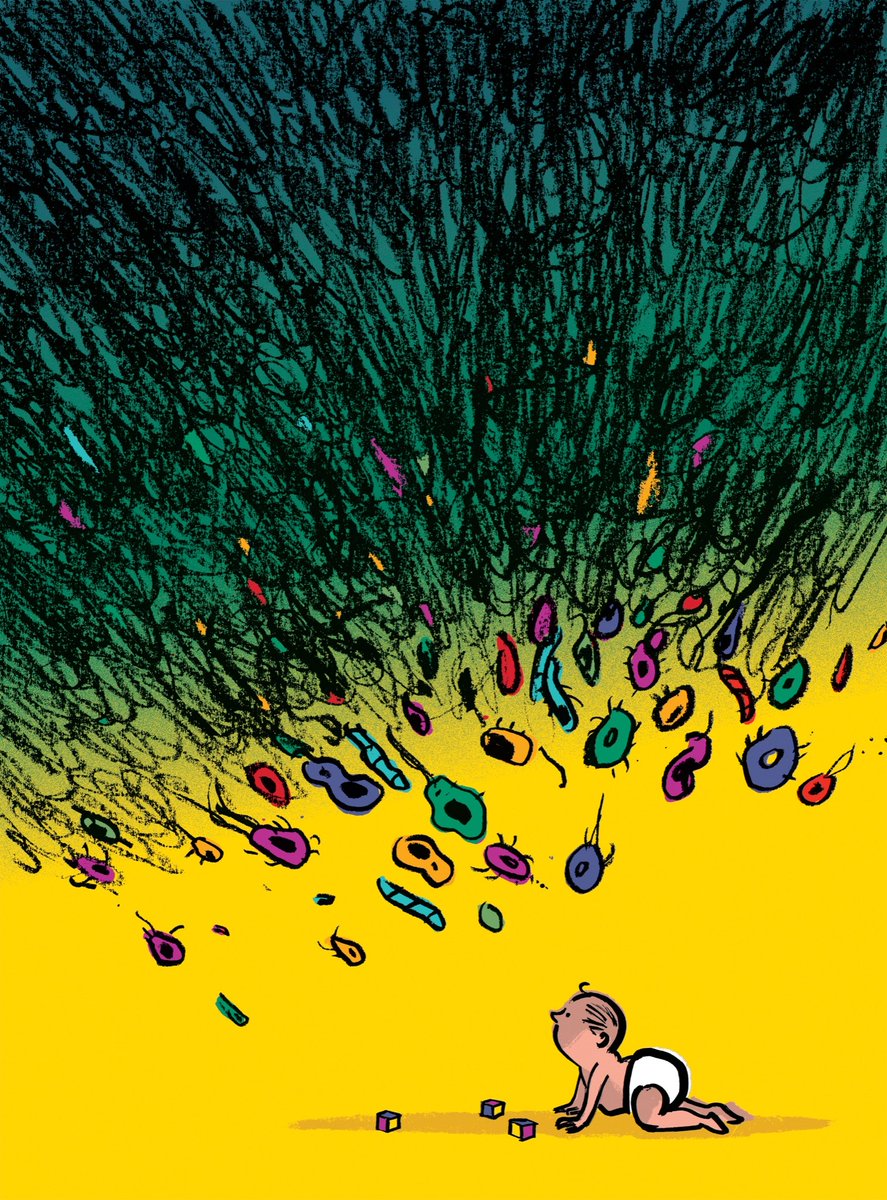

But how do organisms build their optimal (or near optimal) network architectures? There is no grand design: they build and adapt their networks based on local rules that modify the link strength based on local information.

These local adaptation rules are very powerful! Depending on the adaptation parameters, the networks can form to optimally perform a broad array of functions, and can adapt when conditions are changing. This happens all the time in our circulation.

What are other principles that networks might care to optimize? They can be uniformity of nutrient delivery, minimization of average pressure drop in the network, robustness, time it takes to deliver the load and more. There's a lot of very interesting recent work exploring this!

Da Vinci noticed the many similarities between human circulation and rivers. The study of vascular systems can teach us a lot about other flow networks, natural or human-made!

Thanks to the fantastic #EngageDBIO team for commissioning this #DBIOTweetorial and takeover of @ApsDbio today, and for the great content they bring to our community! Have fun sciencing!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh