If you had Ames, Iowa on your bingo card for hotbeds of innovation research — Bingo. Indeed the technology adoption curve (aka the most important curve in history) was invented by rural sociologists at Iowa State College some 70 years ago.* A little history.

https://twitter.com/oliverbeige/status/1389247143022628864

WW2 put pressure on US food supplies, and a variety of technological innovations in agriculture promised improved yields. The rural sociologists were mostly concerned how these improved technologies could be made attractive to farmers, a notoriously skeptical bunch.

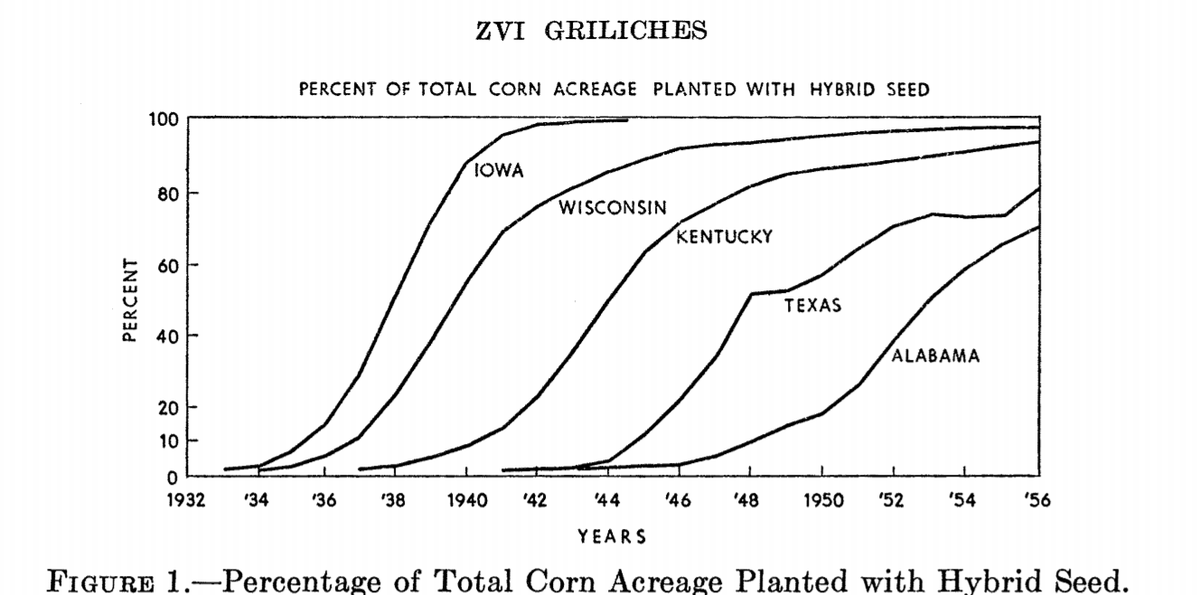

In the 1940s two researchers at ISC, Bryce Ryan and Neal Gross, conducted field research on how Iowa famers adopted the novel hybrid seed corn. Their report already contained the key ingredients: risk preferences, social contagion, geographic spread, and the logistic curve.

Early work focused on the individual decision process and mapped it into 5 deliberation stages: Awareness, Interest, Evaluation, Trial, Adoption; summarized in a special report called "The Diffusion Process" by ISC sociologists Joe Bohlen and George Beal in 1957.

An accompanying pamphlet called "How farm people accept new ideas" already proposed to speed up the adoption process by seeding the learning network with a new type of adoption leader, or, as we would call them today: social influencer.

In their report, George Beal and Joe Bohlen already delineated the means of communication by which the various types of adopters, clustered by risk preference into five categories, could be reached: from friends and neighbors to salesmen, mass media, and govt agencies.

One of George Beal's students at ISC, Everett Rogers, became a professor Ohio State. In 1962 he published a book based on his dissertation called "The Diffusion of Innovations", which became one of the most-cited publications in the social science.

Rogers also pointed out the role of the "invisible college", researchers at various institutions sharing a paradigmatic framework, in the diffusion of new knowledge. In the case of the adoption curve itself, that college was mostly made up of Midwestern land grant schools.

Ryan and Gross did their early work under the head of the department of economics and sociology, Theodore W. Schultz, the 1979 Nobelist and still the only agricultural economist to receive the prize. Schultz himself was very interested in how farmers picked up new knowledge.

But Schultz left Iowa State in 1943 over the fallout of what has become known as the oleomargarine wars, when he took on the powerful Iowa dairy industry. He joined the U Chicago econ program and steered it to national fame, in what might be called the "margarine revolution".

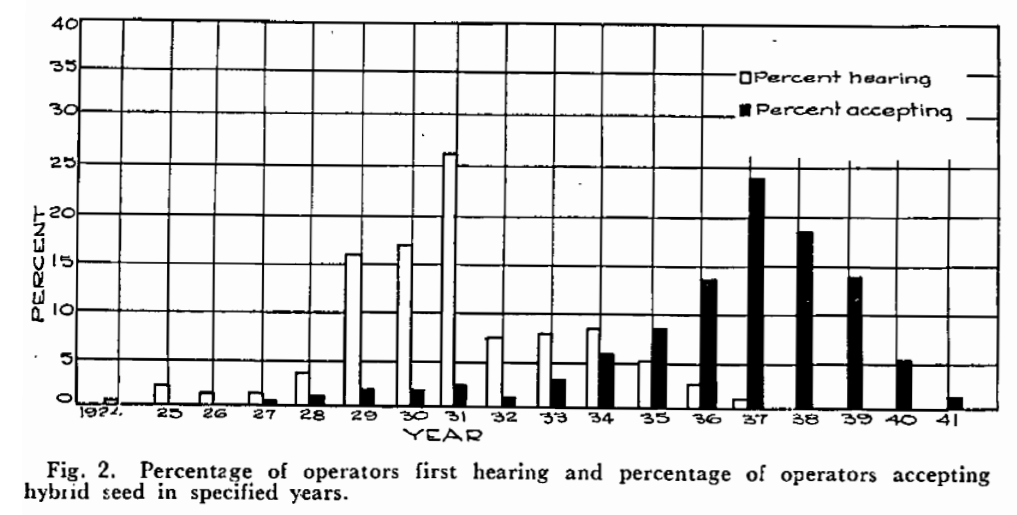

So it was left to Schultz's PhD student Zvi Griliches to work out the economic angle of the technology adoption process, which he did with his 1957 Econometrica article "Hybrid corn: an exploration in the economics of technological change", focusing on geographic spread.

Everett Rogers later joined the Stanford faculty, which is likely where Geoffrey Moore discovered the adoption curve and added his own "chasm", all while failing to mention those whose intellectual efforts preceded his own.

https://twitter.com/oliverbeige/status/1389247496623382532?s=20

*As Valente & Rogers point out in their history of the adoption curve, Ames, Iowa might only be the origin of the US research, and the true inventor was more likely French professor Gabriel Tarde with his 1903 book, "The Laws of Imitation".

@threadreaderapp unroll unspool unravel plz ol buddy

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh