Happy #Eurovision2021 everybody! Apart from the songs #Eurovision itself was a pioneering and often chaotic attempt to collaborate on new technology across Europe. And it only happened because of Queen Elizabeth ll.

Let's look back at the birth of European broadcasting...

Let's look back at the birth of European broadcasting...

After WWll Britain and France quickly restated their TV services. Each had different standards: the BBC's 405-line standard quickly allowed for full national coverage, but France's 819-line format needed more powerful transmitters which reduced its broadcast range.

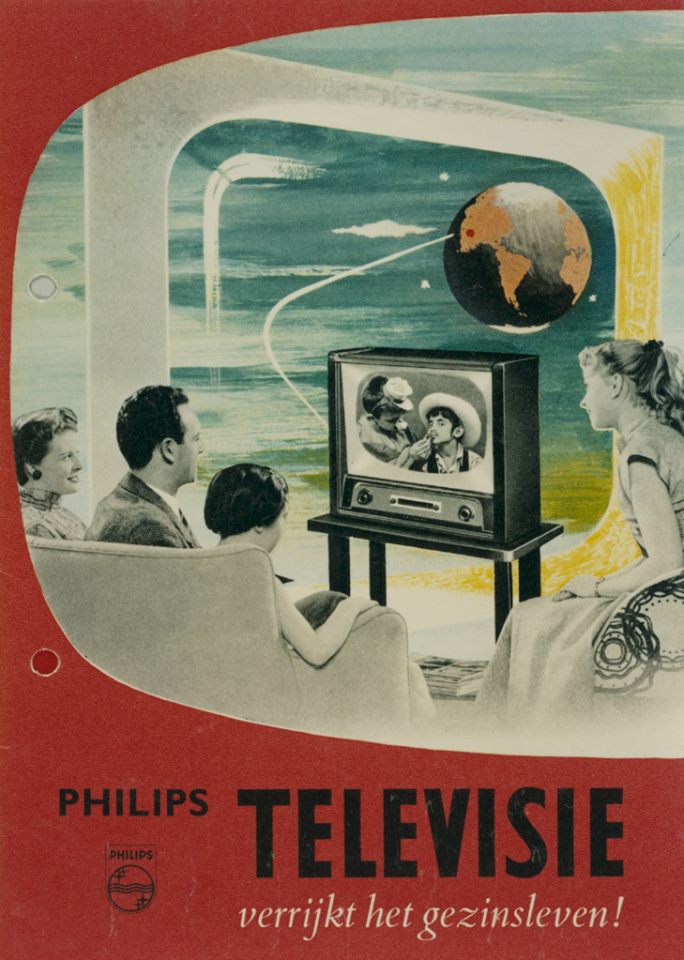

And by 1950 Holland had a TV service using a 625-line standard. However Belgium was caught in the middle: should it use the Dutch or French standard? In a classic euro-fudge it chose both. This made Belgium a pioneer of TV broadcast signal conversion.

On 13 February 1950, broadcasters from 23 European nations met in Torquay to create a common market for TV programme exchanges: the European Broadcasting Union (EBU).

It was a bureaucratic nightmare - nobody could agree anything and everyone objected to something.

It was a bureaucratic nightmare - nobody could agree anything and everyone objected to something.

The term #Eurovision was coined by the Evening Standard newspaper in 1951 to describe the EBU's efforts. Frustrated with its slow progress the UK and France set up their own cross-channel live link in 1952, broadcasting a week's worth of programmes in both countries.

But broadcasting live TV across Europe's patchwork of networks was a huge challenge. Before the launch of Telstar in 1962 overland links were needed between transmitters. Signal conversion between the 3 European standards also had to happen. That was tricky - and expensive.

In 1952 the BBC decided to make the upcoming live broadcast of Queen Elizabeth's coronation available across Europe, building on the success of their 1952 cross-channel pilot. Six nations agreed to take part. However they only told the EBU of their plans in 1953.

The EBU was furious: the BBC were stealing #Eurovision from them! In fact the EBU had produced very little in its first two years except arguments, but it aggressively muscled in on the Coronation plan and demanded the BBC/RTF infrastructure stay in place after the broadcast.

To be fair to the BBC it did share a lot of its experience and knowledge with the EBU in the 1950s, especially on outside live broadcasts. As for the Coronation, the ramshackle cross-Europe TV network wobbled, but it worked: #Eurovision was a reality.

The next EBU conference in London discussed how to build on the Coronation success. They agreed to a 1954 Summer Season of 18 live programmes broadcast across eight counties, including nine matches from the World Cup in Switzerland. It would be a mammoth undertaking.

A control centre was set up in Lille town hall to co-ordinate 41 relay stations, three signal converters and 44 transmitters across 5,000 miles of Europe. On 6 June 1954 #Eurovision formally launched with the Narcissus Festival parade from Montreux, followed by the Pope.

Making #Eurovision 1954 was stressful: getting equipment through customs was a nightmare; complex negotiations were needed with musicians around royalties; OB cameras battled with local authorities for access to the best filming spots. Executives soon dubbed it 'Neurovision.'

But the public approved of the effort. Most countries had only one or two broadcasters showing domestic programmes, so #Eurovision was a genuine 'window on Europe.' The idea that shared live TV could make previously warring nations better understand each other was a powerful one.

The main problem with Eurovision however was what to broadcast: apart from sport what had international appeal regardless of national language? In January 1955 Eurovision executives met to discuss a new idea: a European Cup for amateur variety artists - the Top Town Programme!

Fortunately they also discussed another idea, a European song contest - the Eurovision Grand Prix. Lugano in Switzerland was selected as the venue, even though it had no TV reception or transmitter. Switzerland's only outside broadcast van was sent from Zürich to cover the event.

The first Eurovision Grand Prix was broadcast live on 24 May 1956 to 10 countries. Seven nations fielded singers, performing two songs each. An international jury in the studio awarded up to 10 points for each song. The winner was Switzerland's Lys Assia with the song 'Refrains.'

Eurovision has since become a worldwide broadcasting phenomenon, and it's easy to laugh at its cheesy format and often baffling song choices. But it was a monumental technical effort to make it happen at all. #Eurovision - Twitter salutes you!

(The greatest song never to win #Eurovision...)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh