The past few days I've been pondering over an interesting terminological conundrum in the use of the term madd 'length'/mamdūd 'lengthened' by al-Dānī (but also ibn Mujāhid), which seem to be mismatched with what he considered to be 'lengthened' in recitation.

So first some basics of Quranic recitation: the long vowels ā, ī and ū (and ē, ǟ and ǖ) are obligatorily made overlong whenever:

1. followed by a hamzah (glottal stop), e.g. السمآء as-samāāʾ "the sky"

2. in a closed syllable, e.g.: دآبّة dāābbah "animal"

This is called madd.

1. followed by a hamzah (glottal stop), e.g. السمآء as-samāāʾ "the sky"

2. in a closed syllable, e.g.: دآبّة dāābbah "animal"

This is called madd.

When there is disagreement among readers on such al-Dānī describes the long vowel that precedes the hamzah or consonant as "madd", rather than as ʾalif.

Ḥamzah and al-Kisāʾī: جعله دكا here with madd and hamz without tanwīn (dakkāʾa) and the rest: with tanwīn and no hamz (dakkan)

Ḥamzah and al-Kisāʾī: جعله دكا here with madd and hamz without tanwīn (dakkāʾa) and the rest: with tanwīn and no hamz (dakkan)

Nāfiʿ and ʾAbū Bakr: له شركا with kasr of the šīn and ʾiskān of the rāʾ with tanwīn (širkan). The rest: with ḍamm of the šīn, fatḥ of the rāʾ, madd and hamzah without tanwīn (šurakāʾa).

For closed syllables, this jargonic use is not found (but also it's very rare).

For closed syllables, this jargonic use is not found (but also it's very rare).

What's important is the term madd here is essentially equivalent to 'alif', but it is ONLY used when a hamzah is involved. This is even the case when we are looking at very comparable cases, for example when some of the readers read a noun as a FiʕāL pattern:

Nāfiʿ: دفع الله here an in al-Ḥajj with kasr of the dāl and an ʾALIF after the fāʾ (difāʿu). The rest read it with fatḥ of the dāl, ʾiskān of the fāʾ without ʾalif (dafʿu).

Ibn Kaṯīr: كان خطا with kasr of the ḫāʾ, fatḥ of the ṭāʾ with MADD (ḫiṭāʾan) (etc.)

Ibn Kaṯīr: كان خطا with kasr of the ḫāʾ, fatḥ of the ṭāʾ with MADD (ḫiṭāʾan) (etc.)

This systematic difference in use of ʾALIF when no hamzah follows and MADD when hamzah does follow, naturally led me to think that al-Dānī is referring to the fact that the vowel is pronounced overlong.

However, he also uses madd for long vowels after hamzah!

However, he also uses madd for long vowels after hamzah!

For example:

The two of the holy cities, Ibn ʿĀmir and Ḥafṣ: لروف with madd whenever it occurs (raʾūf) and the rest with qaṣr (i.e. shortness) (raʾuf).

Ibn Kaṯīr: ما اتيتم with qaṣr (ʾataytumū) [...] and the rest with madd (ʾātaytum)

The two of the holy cities, Ibn ʿĀmir and Ḥafṣ: لروف with madd whenever it occurs (raʾūf) and the rest with qaṣr (i.e. shortness) (raʾuf).

Ibn Kaṯīr: ما اتيتم with qaṣr (ʾataytumū) [...] and the rest with madd (ʾātaytum)

However, there is only one reciter that pronounces long vowels followed by hamz with madd in the technical sense, and that is Warš ʿan Nāfiʿ (and there as an option). As al-Dānī is clearly using the term madd here to refer to readers other than Warš, this can't be it.

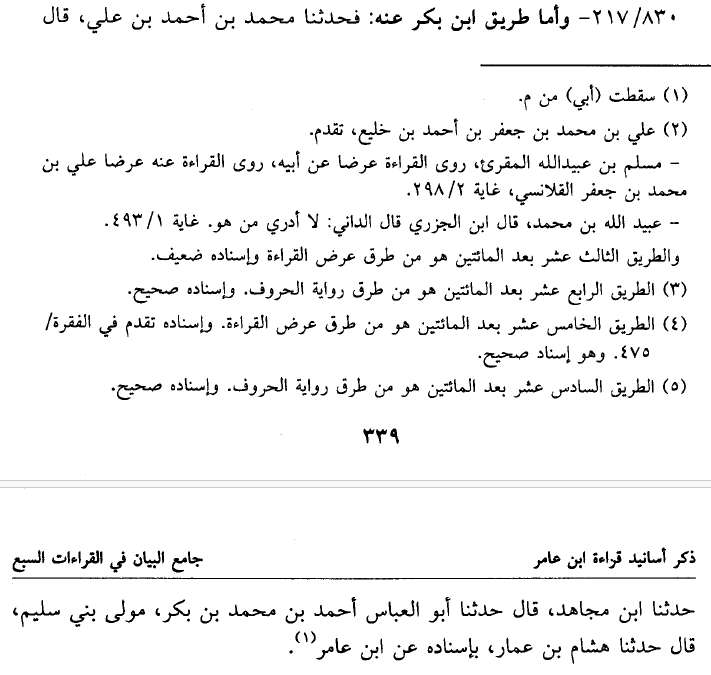

Since Warš was the dominant reading in al-Dānī's 11th c. Andalusia, one might imagine that he simply picked up this way of referring to it from an underlying Warš-like phonology. But the 10th century Baghdādī Ibn Mujāhid has very similar use, using the term mamdūd for these.

One might also wonder whether this practice is purely orthographic. Today, hamzah followed by ā is also spelled آ (e.g. القرآن for al-qurʾān). But this was much less widespread in medieval times. And in Andalusia unheard of (there القرءان is used).

Moreover, it is not all that obvious that these authors would use purely orthography-inspired terminology. Arabic grammatical theory and terminology is notoriously non-orthographic. But why is it then that hamz + long vowel is called madd/mamdūd?

This practice might be innovative. When examining the works of the earliest grammarians, Sībawayh and al-Farrāʾ, they only use the term mamdūd in places where the vowel would indeed be overlong.

Thus, al-Farrāʾ calls the reading fa-ḏāānnika for فذانك 'mamdūd'.

Thus, al-Farrāʾ calls the reading fa-ḏāānnika for فذانك 'mamdūd'.

Likewise the form zakariyyāāʾu is called mamdūd whereas the form without hamzah zakariyyā is called maqṣūr.

Sībawayh, I believe, only uses the term mamdūd to refer to ā followed by hamzah (and perhaps even only word-finally).

So what is going on?

Sībawayh, I believe, only uses the term mamdūd to refer to ā followed by hamzah (and perhaps even only word-finally).

So what is going on?

I don't have a good answer, but for the use of the ʾalif, the practice is strikingly reminiscent of a (likewise strange) but really ancient orthographic practice of vocalised Qurans. Ancient Qurans used red dots to write the vowels, and the system has quite some subtleties.

A red dot placed at the top of an ʾalif can be placed to the right or the left of the ʾalif. In word-final position this marks the difference between aʾ and āʾ. Thus, the apocopate ʾin yašaʾ (إن يشأ) would get a dot to the right of the ʾalif, ʾan yašāʾa (أن يشآء) to the left.

But, somewhat surprisingly, word-initially both positions are ALSO used. Where the dot to the right is used for hamzah followed by short a, whereas hamzah followe by long ā is spelled with a dot to the left. In other words: ʾā and āʾ are spelled the same:

1. ʾataytum

2. ʾātaytum

1. ʾataytum

2. ʾātaytum

So, the ancient vocalisation practice matches that of the terminology as used by al-Dānī and Ibn Mujāhid: they write hamzah followed by ā the same as ā followed by hamzah. Just like al-Dānī calls the vowel in both those situations 'madd'.

The parallel is not perfect. For example, in Quranic manuscript hamzah followed by ī and ū are spelled clearly distinct from ī and ū followed by hamzah.

1. la-raʾūfun / as-sūʾu

2. ʾīmānihī / bārīʾun (font displays the vowels below the yāʾ, sorry)

1. la-raʾūfun / as-sūʾu

2. ʾīmānihī / bārīʾun (font displays the vowels below the yāʾ, sorry)

al-Dānī actually strongly disagreed with the practice of vocalizing the ʾā with a dot to the left of the ʾalif. He argued: the dot is the hamzah and it clearly comes BEFORE the ʾalif, therefore it should be written before it, and is quite vocal about it.

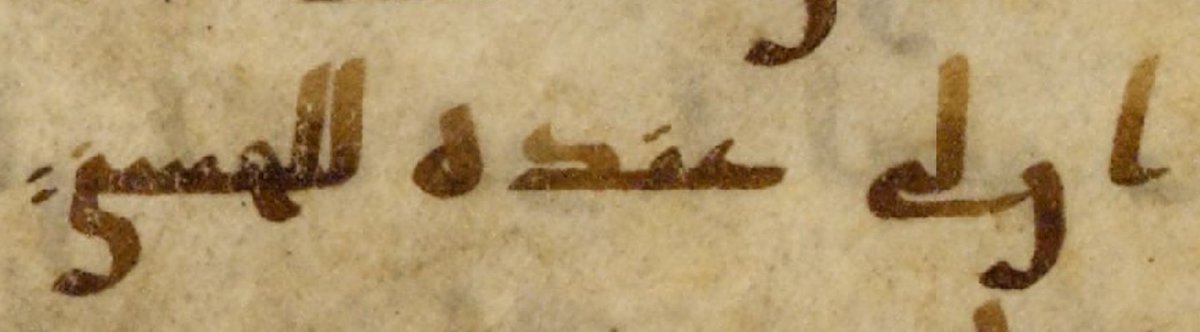

This is indeed the Maghrebi practice, wa-ʾāmana, with yellow dot before the ʾalif.

So if the practice of referring to such sequences as mamdūd has its origins in the vocalisation practice, certainly no awareness of that is present in al-Dānī's own work.

So if the practice of referring to such sequences as mamdūd has its origins in the vocalisation practice, certainly no awareness of that is present in al-Dānī's own work.

So that's it! Not a satisfying answer. Just an odd practice. Would love to hear if anyone has any smart solutions to this conundrum.

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

Oh, almost forgot! I recently published an article on the use of the maddah sign in non-Quranic manuscripts, a topic that is certainly related to this conundrum. The article is Open Access, read it here!

doi.org/10.1163/187846…

doi.org/10.1163/187846…

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh