New paper from @joans and me! A pan-cancer, cross-platform analysis identifies >100,000 genomic biomarkers for cancer outcomes. Plus, a website to explore the data (survival.cshl.edu) and a (controversial?) discussion of “cause” vs. “correlation” in cancer genome analysis.

https://twitter.com/biorxivpreprint/status/1399950911573737474

We used every type of data collected by TCGA (RNASeq, CNAs, methylation, mutation, protein expression, and miRNASeq) to generate survival models for each individual gene across 10,884 cancer patients. In total, we produced more than 3,000,000 Cox models for 33 cancer types.

Within each cancer type, we identified thousands of biomarkers for favorable and dismal patient outcomes. The most common adverse biomarkers included overexpression of the mitotic kinase PLK1, methylation of the transcription factor HOXD12, and mutations in TP53.

GO term analysis revealed common gene groups among adverse and favorable biomarkers, including cell cycle genes (upregulated in deadly cancers) and developmental transcription factors (methylated in deadly cancers).

We could use these biomarkers to stratify patient outcomes in clinically-ambiguous situations, including Stage 1a breast cancer and Gleason 7 prostate cancer. In general, gene expression and DNA methylation biomarkers provided the most prognostic information.

So now here’s where it gets weird: aside from mutations in TP53, we didn’t see many cancer driver genes score as strong biomarkers in our prognostic analysis. KRAS, EGFR, RB1, PIK3CA, RB1, NF1… mutation, methylation, or altered expression of these genes wasn’t really prognostic.

In the literature, if some gene is associated with worse cancer outcomes, then that is typically presented as evidence that that gene is an important cancer driver. But clearly KRAS and PIK3CA are important cancer drivers and they didn’t score in our analysis… so what gives?

To investigate this, we analyzed lists of cancer driver genes, and then we compared their prognostic significance to randomly-permuted gene sets. Surprisingly, verified oncogenes were no more likely to be prognostic than any randomly chosen gene in the genome!

For instance - KRAS mutations clearly drive lung cancer. But KRAS mutations in lung cancer are *not* associated with worse patient outcomes. In some cases, mutations in specific oncogenes are associated with *better* outcomes, not worse outcomes.

If you infer the importance of a gene from survival analysis (which is exceptionally common in the literature, and is something I’ve previously done myself) - you could accidentally conclude that CENPA is a more important driver of prostate cancer progression than MYC:

In general, our analysis provides genome-wide evidence that inferring *causation* (gene A is a driver of cancer progression) from *correlation* (gene A is overexpressed in deadly cancers) is not appropriate for patient outcome analysis, even if it’s commonly done.

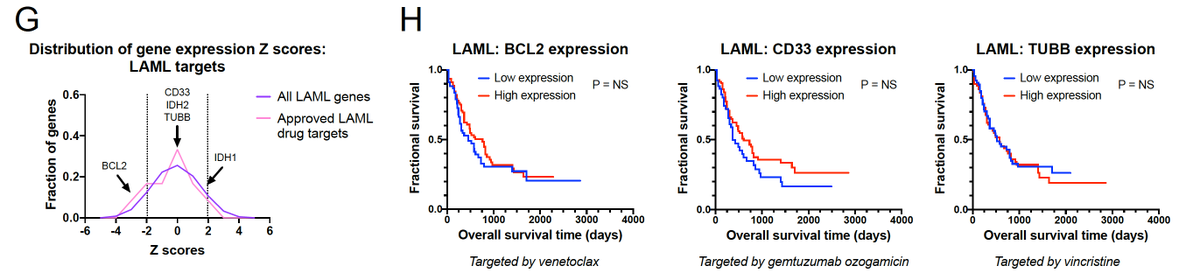

Next, we looked at cancer drug targets. Again, it is routine to see the fact that a gene is associated with deadly cancers presented as evidence that that gene is a good drug target. But is this link justified by the data?

We looked at the targets of all FDA-approved cancer drugs, and we found that these drug targets were no more likely to be prognostic than any randomly-selected gene in the genome!

Consider PD1 as a drug target. High levels of PD1 (PDCD1) are associated with patient survival. So you might think that PD1 inhibitors would kill people! But cancers don’t work like that - survival correlation is not causation - and PD1 inhibitors in fact prolong survival.

(You could imagine that this is a type of post-hoc fallacy - maybe these genes are non-prognostic because of the existing therapies. But we did a sub-analysis on drugs approved after 2017 [post-TCGA], and we observed the same pattern).

Then we asked - what happens if you target the worst adverse features in the genome? Maybe those are still the best drug targets? Among the top 50 prognostic factors in the genome, we found that 16 have been targeted in clinical trials, and 15 of them have failed.

We believe this is because the most prognostic factors are not selective oncogenes. They’re housekeeping cell cycle genes that are ubiquitously expressed, and they’re essential across cell types. No cell type-selectivity = systemic toxicity and trial failure.

Successful cancer drug targets may be adverse biomarkers, favorable biomarkers, or they may have no survival correlation whatsoever. Our data demonstrates that this type of prognostic analysis should be uncoupled from therapeutic target development.

To put this in perspective - imagine a KM plot of 10,000 senior citizens: “people receiving dialysis” vs “people not receiving dialysis”. Individuals receiving kidney dialysis are more likely to die than individuals who are not receiving dialysis...

Based strictly on this correlative observation, one could assume that kidney dialysis kills people! Yet, we know that people receiving dialysis are likely to be older and have several medical comorbidities, and dialysis saves their lives. Same thing in cancer genomics!

Inferring functional relationships and prioritizing drug targets based on correlative outcomes analysis may be inappropriate, as these relationships can be fraught with confounding variables and spurious associations.

So, let me know what you think, and take a look at our website - survival.cshl.edu. 3 million Kaplan-Meier plots to explore and lots more exciting findings to uncover. Feedback welcome!

I should add - I was playing around with some of the ideas in the paper in the thread linked below. It goes a little deeper into the drug target analysis and the misinterpretation of what survival curves mean:

https://twitter.com/JSheltzer/status/1150828437680074752

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh