Job growth picked up in May, but was still weaker than in March. Big-picture, we're still down 7.6 million jobs from before the pandemic.

Remote work continuing to fall as more offices reopen. 16.6% of workers were remote in May, down from peak of 35.4%. 30% of professional workers, down from 57.4%.

The number of workers reporting that they are on temporary layoff fell below 2 million for the first time since the pandemic began. Permanent layoffs also falling, but more slowly.

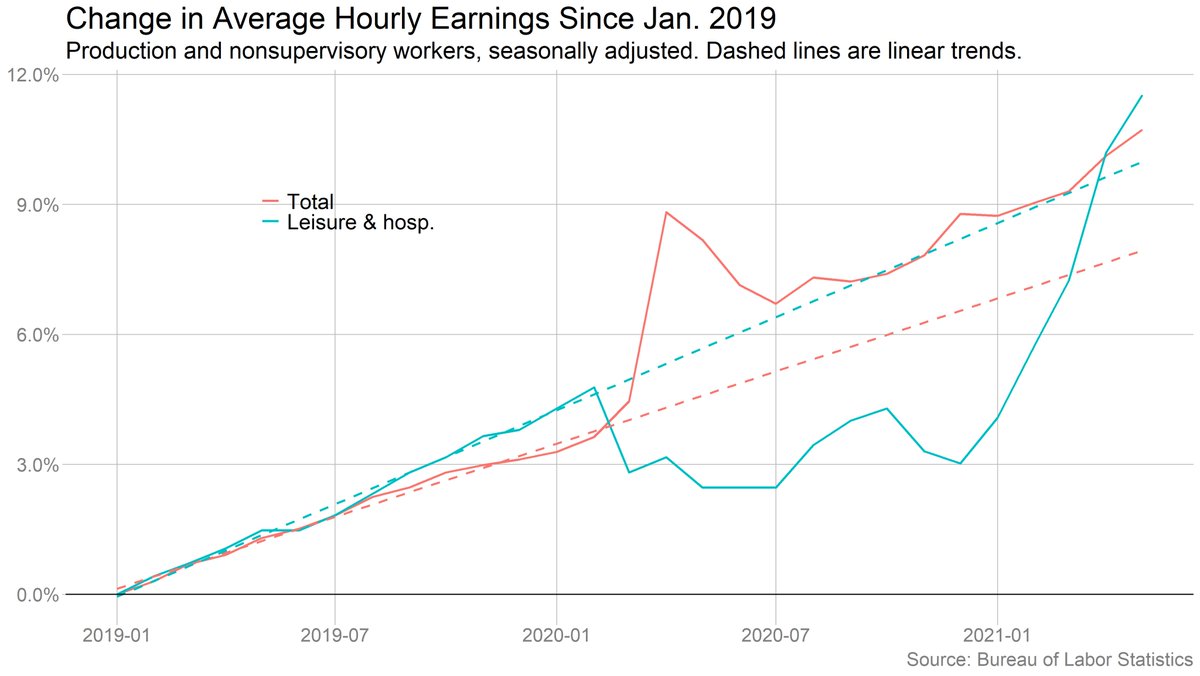

Hourly earnings growth in leisure and hospitality (nonsupervisory) remained high in May, but came back down to earth a bit (this chart shows three-month change, but one-month slowdown even more significant).

But note that hourly pay in leisure and hospitality is now running above its pre-Covid trend. Wouldn't make too much of one month of data, but if that continues, it's notable.

(More on wages from me and @jeannasmialek in today's print edition: nytimes.com/2021/06/03/bus…)

(More on wages from me and @jeannasmialek in today's print edition: nytimes.com/2021/06/03/bus…)

The official unemployment rate fell to 5.8% in May. Adjusting for misclassification and labor force exits (roughly what the Fed has recently been discussing lately), unemployment was 8.7%, down just a tick from April.

Labor force participation was down slightly overall last month, and flat for prime-age (25-54) workers. That's pretty disappointing given the hole we're in

Notably, participation among prime-age women actually ticked down last month. Monthly data bounce around, so wouldn't read too much into that, but the bigger picture is clear: Women left the labor force in greater numbers during the pandemic and have made little recent progress.

Although if we look at employment (rather than participation) and at all adults (not just prime age), women have caught up to men and both now face the same jobs deficit.

Different story by race. Black and Hispanic workers still face a larger jobs deficit than white and Asian workers.

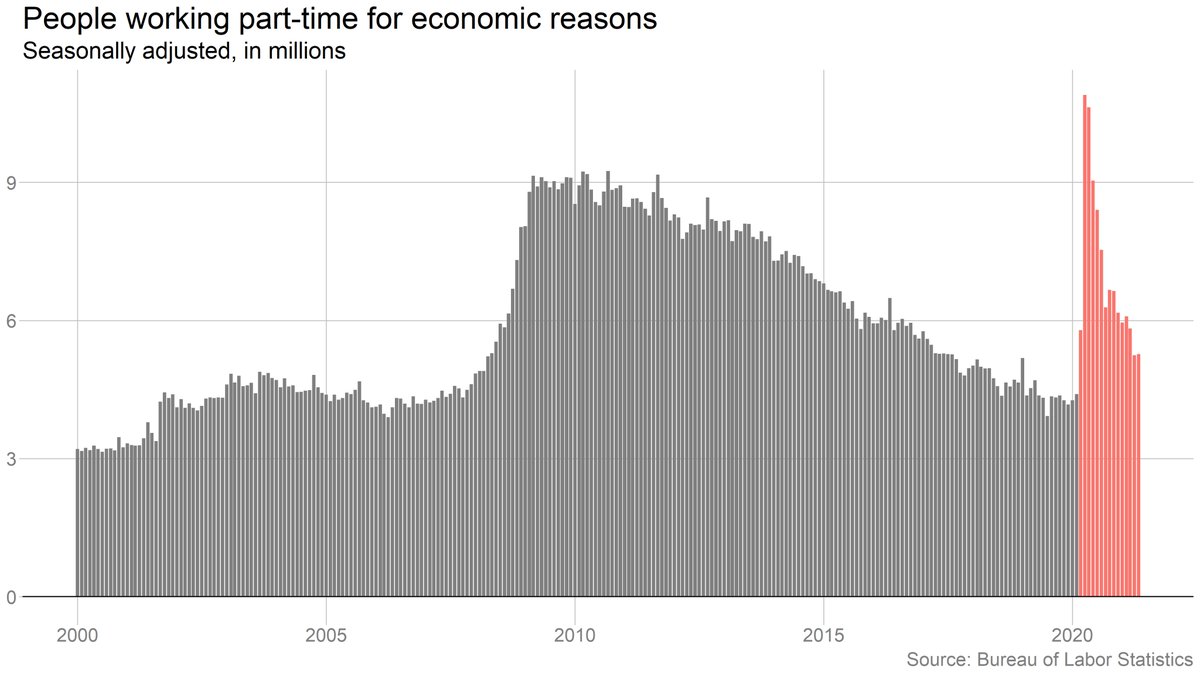

In my story yesterday, I highlighted (at @ConstanceHunter's suggestion) involuntary part-time workers as a sign of labor supply. By that measure, not much sign of a labor shortage: "part-time for economic reasons" basically flat last month.

nytimes.com/2021/06/03/bus…

nytimes.com/2021/06/03/bus…

This is interesting: Unemployed people were roughly as likely to leave the labor force last month as to find jobs.

Meanwhile, most people who got jobs last month came from outside the labor force -- though that share is still below its prepandemic level.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh