What you see below is a cube in four dimensions.

Because humans can't see in more than 3D, it is challenging to make sense of it for the first time. However, there is a simple yet beautiful pattern behind.

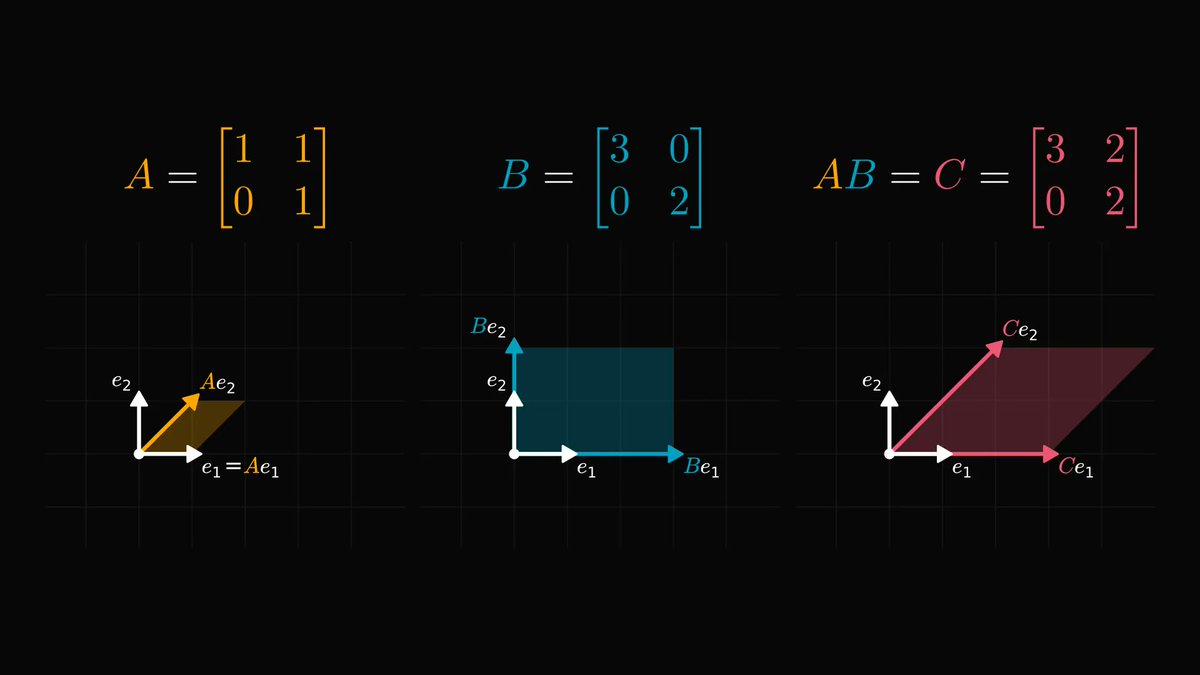

This is how the magic is done!

Because humans can't see in more than 3D, it is challenging to make sense of it for the first time. However, there is a simple yet beautiful pattern behind.

This is how the magic is done!

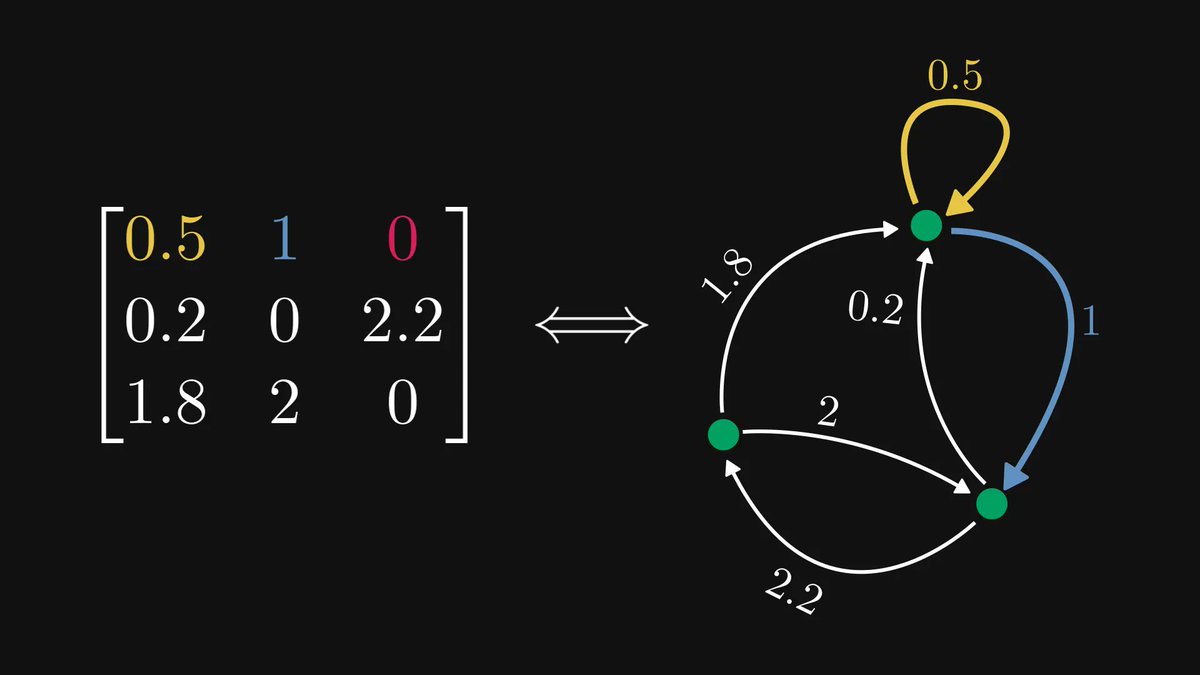

To move beyond and construct a cube in two dimensions, also known as a square, we simply copy a one-dimensional cube and connect each original vertex with its copy.

(These new edges are colored blue.)

(These new edges are colored blue.)

You can probably guess the pattern by now.

Copying a cube's graph and connecting each of its vertices with its corresponding copy brings it to the next dimension.

This is how it looks in 3D.

Copying a cube's graph and connecting each of its vertices with its corresponding copy brings it to the next dimension.

This is how it looks in 3D.

Repeating this process one more time, we obtain a tesseract, that is, a cube in four dimensions.

(I stretched the new edges a bit to make it easier to see the pattern.)

(I stretched the new edges a bit to make it easier to see the pattern.)

I have always found this pattern quite beautiful.

Geometry intrigued me since I was a child, and when I discovered how to draw a tesseract, I was over the moon.

Small things such as this ignited my desire to be a mathematician, and I still enjoy playing around with fun math.

Geometry intrigued me since I was a child, and when I discovered how to draw a tesseract, I was over the moon.

Small things such as this ignited my desire to be a mathematician, and I still enjoy playing around with fun math.

I regularly post deep dive threads about mathematics and machine learning, explaining (seemingly) complex concepts in a simple way.

If you also love to look beyond the surface and understand how things work, consider giving me a follow!

If you also love to look beyond the surface and understand how things work, consider giving me a follow!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh