Most rocky worlds are what we call "one-plate planets": they have a single, continuous outer shell that we call the lithosphere.

Mercury (shown here), Mars, the Moon, Io... all one-plate planets.

(2/n)

Mercury (shown here), Mars, the Moon, Io... all one-plate planets.

(2/n)

We've long known that Venus is a lot more complex than those other, smaller worlds—but how hasn't exactly been clear.

It doesn't have plate tectonics like Earth. Is it a single shell? Did it *ever* have a mobile surface? What drove that motion?

That's where we come in.

(3/n)

It doesn't have plate tectonics like Earth. Is it a single shell? Did it *ever* have a mobile surface? What drove that motion?

That's where we come in.

(3/n)

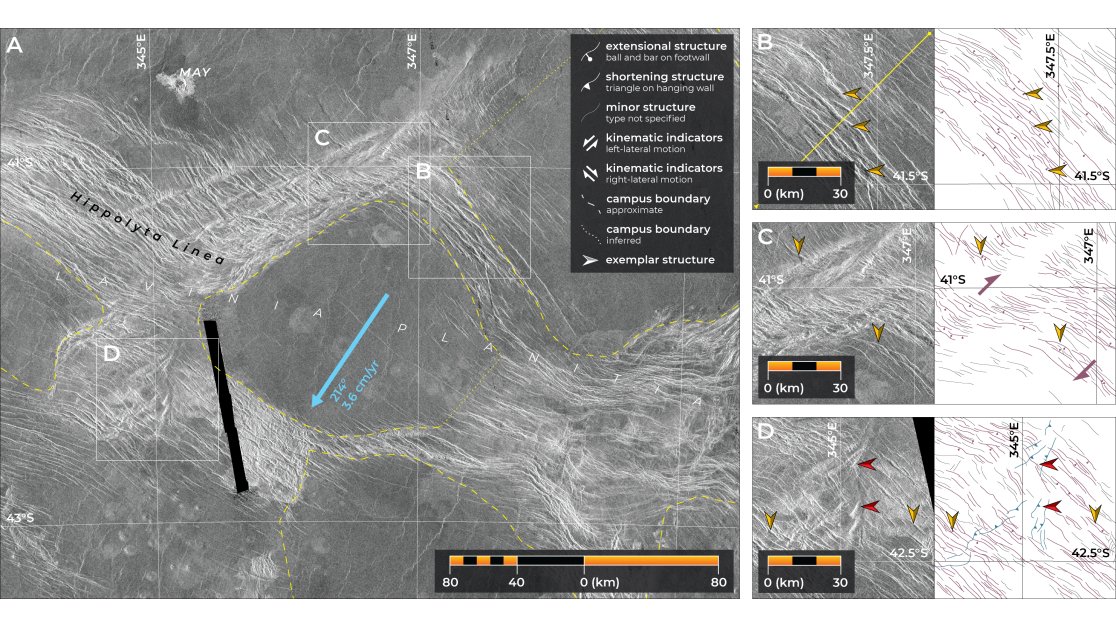

We took old data from @NASA's Magellan mission (which ended when ST:TNG did) and started mapping.

There are many narrow bands of tectonic structures on Venus—the stuff in yellow here.

In lots of places those belts outline low-lying areas that are only a little deformed.

(4/n)

There are many narrow bands of tectonic structures on Venus—the stuff in yellow here.

In lots of places those belts outline low-lying areas that are only a little deformed.

(4/n)

@NASA What's important here is that, within those belts of tectonic structures—some of which are where the crust was pushed together, others where it was pulled apart—there's also evidence for stuff having moved side-to-side.

That's really important.

(5/n)

That's really important.

(5/n)

@NASA Here's a map of that vast, low-lying area shown above, but with more geological detail.

Twitter compression aside, here's the take-home:

This is a big lowland, surrounded by tectonic belts that record a lot of horizontal, side-to-side-motion.

This thing moved, y'all.

(6/n)

Twitter compression aside, here's the take-home:

This is a big lowland, surrounded by tectonic belts that record a lot of horizontal, side-to-side-motion.

This thing moved, y'all.

(6/n)

@NASA Here's another example. (This one's my favourite.)

It's a smaller lowland, but by looking at the belts around its edges we can infer that it moved—to the southwest, in this case

***and***

it must have moved geologically recently

(7/n)

It's a smaller lowland, but by looking at the belts around its edges we can infer that it moved—to the southwest, in this case

***and***

it must have moved geologically recently

(7/n)

@NASA We can say that because in lots of cases tectonic structures cut through, and thus must be younger than, the lava flows that make up the plains.

Those flows are some of the youngest on Venus. We don't know *how* young... yet.

But not hundreds of millions of years.

(8/n)

Those flows are some of the youngest on Venus. We don't know *how* young... yet.

But not hundreds of millions of years.

(8/n)

@NASA And remember that smaller low? Here's a more zoomed out view of that region—the small low is near the top.

This region is full of belts. Which show lots of side-to-side motion. And this region is full of lows.

Which we think are individual chunks of Venus' lithosphere.

(9/n)

This region is full of belts. Which show lots of side-to-side motion. And this region is full of lows.

Which we think are individual chunks of Venus' lithosphere.

(9/n)

@NASA If we're right, then these chunks—we call them blocks—seem to have jostled, moved, banged into each other, pulled apart, rotated... in a way that's similar to how pack ice or drift ice behaves.

(10/n)

(10/n)

@NASA We've found this pattern of jostling blocks across Venus.

It's not everywhere, and it doesn't—yet, at least—seem to form a globally interconnected network of blocks.

There might just be regions where the lithosphere fragments, and others where it doesn't.

But why?

(11/n)

It's not everywhere, and it doesn't—yet, at least—seem to form a globally interconnected network of blocks.

There might just be regions where the lithosphere fragments, and others where it doesn't.

But why?

(11/n)

@NASA It's possible that, similar to Earth, Venus' mantle is convecting—moving as it's heated from below—with that motion being transferred to the surface.

So @PeterBJames ran some models to estimate how much stress a convecting interior might apply to the surface.

(12/n)

So @PeterBJames ran some models to estimate how much stress a convecting interior might apply to the surface.

(12/n)

@NASA @PeterBJames Long story short—and short story interesting—we found that the stresses from movement in the interior are *at least* enough to overcome the strength of the lower part of the lithosphere... leading to movement of the surface.

(13/n)

(13/n)

@NASA @PeterBJames It's not plate tectonics like on Earth. These blocks don't subduct.

But it's *similar*—stuff has moved on the surface geologically recently in response, we think, to movement of the interior.

Not quite Earth. But definitely not Mercury, the Moon, or that dullard Mars.

(14/n)

But it's *similar*—stuff has moved on the surface geologically recently in response, we think, to movement of the interior.

Not quite Earth. But definitely not Mercury, the Moon, or that dullard Mars.

(14/n)

@NASA @PeterBJames OK, so should you care?

Friends, OF COURSE you should care!

First off, if stuff moved on Venus in the geologically recent past, do you really think it shut down only a few million years ago? Venus is almost as big as Earth.

Earth has plenty of vigour left.

(15/n)

Friends, OF COURSE you should care!

First off, if stuff moved on Venus in the geologically recent past, do you really think it shut down only a few million years ago? Venus is almost as big as Earth.

Earth has plenty of vigour left.

(15/n)

@NASA @PeterBJames But modern Venus might also hold clues to early Earth.

Much of Venus' lithosphere is probably thin, because the surface is so hot. Early Earth likely had a thin lithosphere, because the interior was hotter than today.

So maybe Venus tectonically resembles young Earth?

(16/n)

Much of Venus' lithosphere is probably thin, because the surface is so hot. Early Earth likely had a thin lithosphere, because the interior was hotter than today.

So maybe Venus tectonically resembles young Earth?

(16/n)

@NASA @PeterBJames And Venus might *also* tell us what to expect on planets that are Earth-sized—which basically means Venus-sized—orbiting other stars.

If so, then we can build on our findings for Venus to calibrate our expectations for how large, rocky exoplanets might work.

(17/n)

If so, then we can build on our findings for Venus to calibrate our expectations for how large, rocky exoplanets might work.

(17/n)

@NASA @PeterBJames We have more to do.

But the Magellan data aren't exactly *great* in terms of what we need.

Thankfully, within the next 10 years we're gonna get a BOATLOAD (as in, petabytes) of new data for Venus, both from @NASA's VERITAS mission (led by @SueSmrekar)...

(18/n)

But the Magellan data aren't exactly *great* in terms of what we need.

Thankfully, within the next 10 years we're gonna get a BOATLOAD (as in, petabytes) of new data for Venus, both from @NASA's VERITAS mission (led by @SueSmrekar)...

(18/n)

@NASA @PeterBJames @SueSmrekar ...and by @ESA's EnVision mission, which is led by the second author on our paper, Rich Ghail (and who steadfastly refuses to join Twitter, so he can't tell when I abuse him).

PETABYTES of new data.

It's going to be wild.

(19/n)

PETABYTES of new data.

It's going to be wild.

(19/n)

@NASA @PeterBJames @SueSmrekar @esa So, that's our paper.

That's why this is potentially a big deal—we've found that our weirdo neighbour is more Earth-like than we knew, and is very possibly tectonically active *now*.

I've skipped a *lot* of detail here, but I hope you enjoyed this thread—and thanks for reading!

That's why this is potentially a big deal—we've found that our weirdo neighbour is more Earth-like than we knew, and is very possibly tectonically active *now*.

I've skipped a *lot* of detail here, but I hope you enjoyed this thread—and thanks for reading!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh