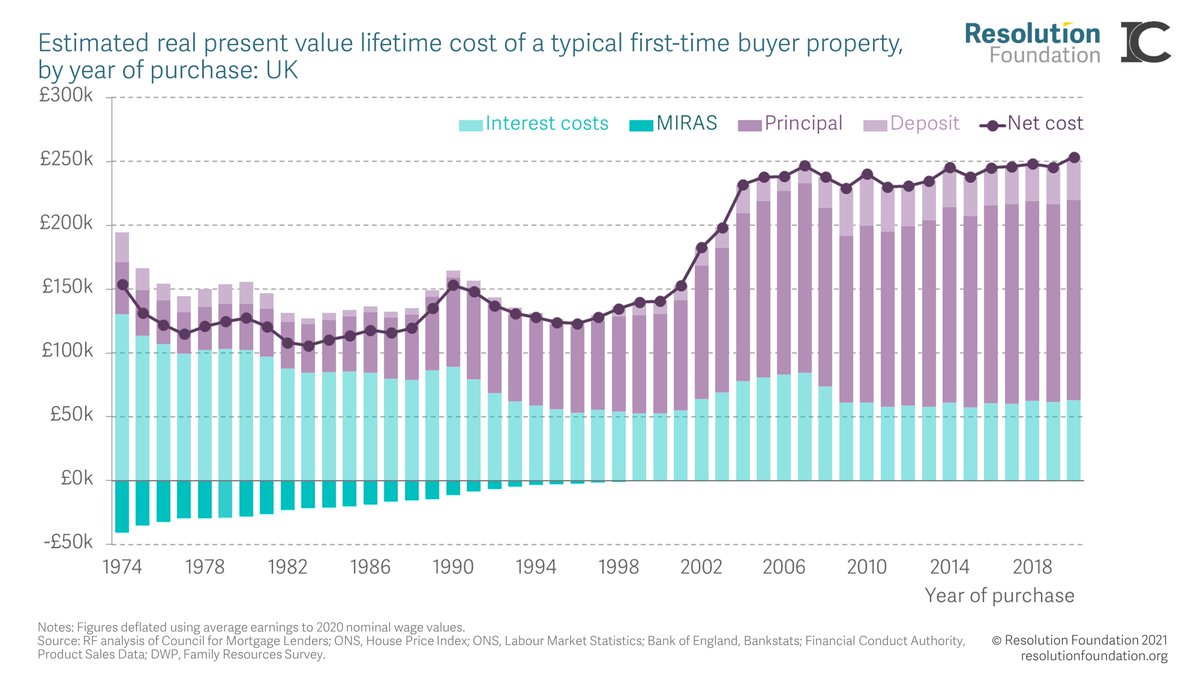

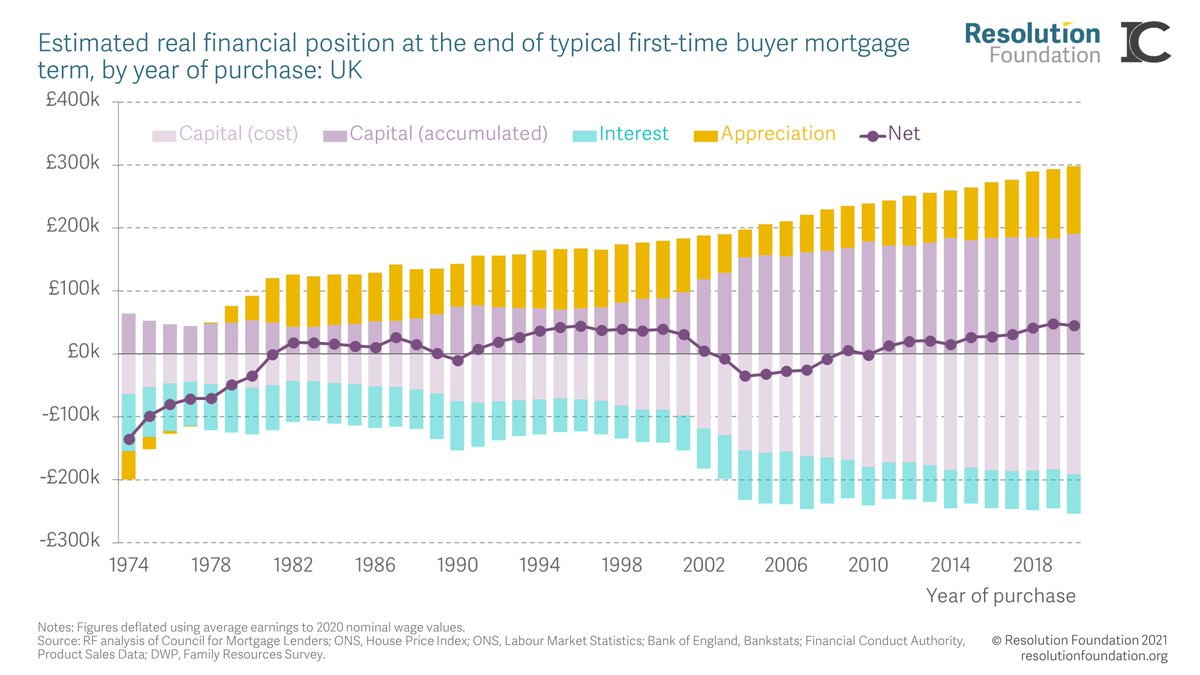

The housing market in a nutshell over the last fifty years? House prices up; interest rates down (although mortgage terms and loan-to-value ratios have changed a bit too).

In new research published today, and funded by @NuffieldFound , we ask which generation has had the better deal when it comes to buying a first home: resolutionfoundation.org/publications/s…

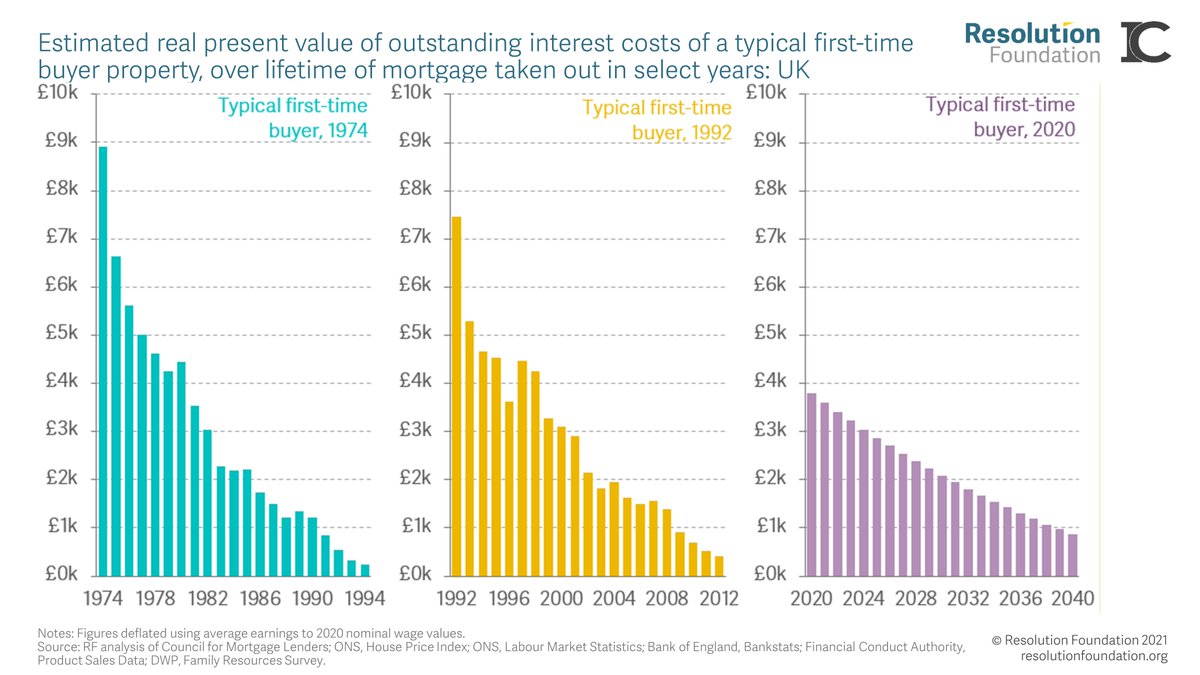

Sky-high interest rates in the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s meant that older generations had a stressful time, especially in the early years of a mortgage...

Over the course of their first mortgage term, however, they actually paid less interest overall than those buying in the run-up to the GFC, not least because they got generous tax relief via MIRAS.

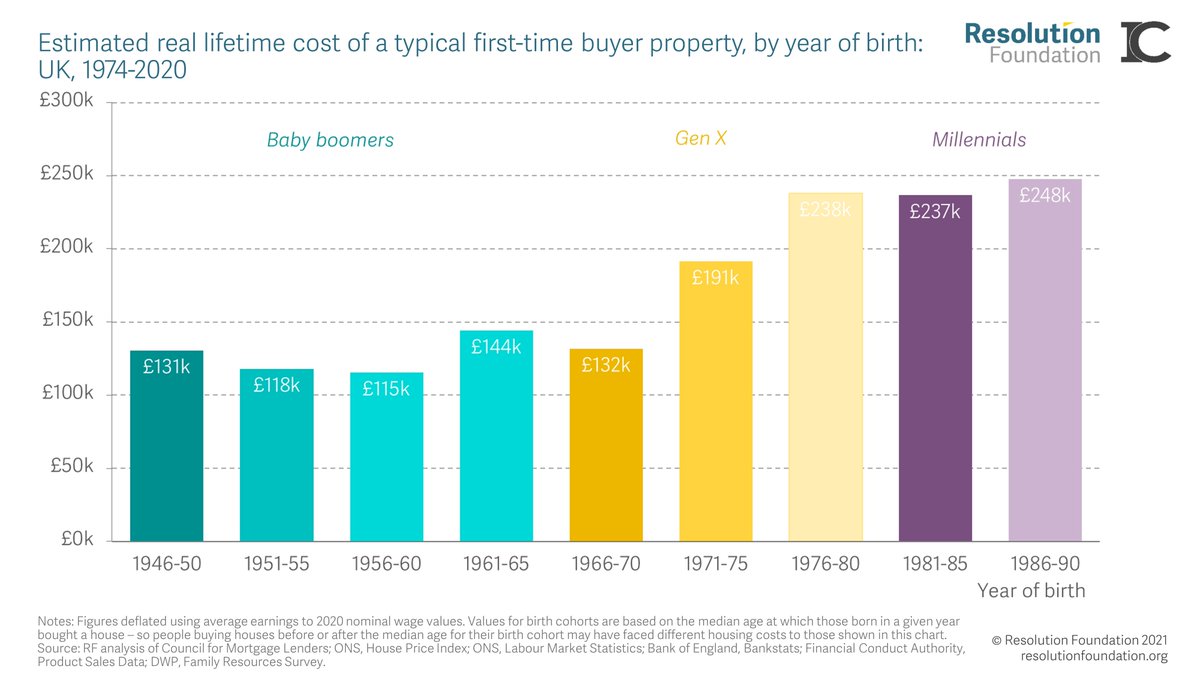

In contrast, today’s wannabe first-time buyers face much higher real house prices, requiring them to find significantly more cash both to get on the ladder in the first place and reach the point when they own their home outright.

But it’s not just millennials who have been hard hit. Total costs of buying one’s first home escalated rapidly for the Gen-Xers too.

These intergenerational differences vary considerably across the country. The typical first time in London in 2020 faced total costs of over £500,000, 2.5 times as much as the typical buyer in the capital in 1974. In the North East, costs changed just 9 per cent over that time.

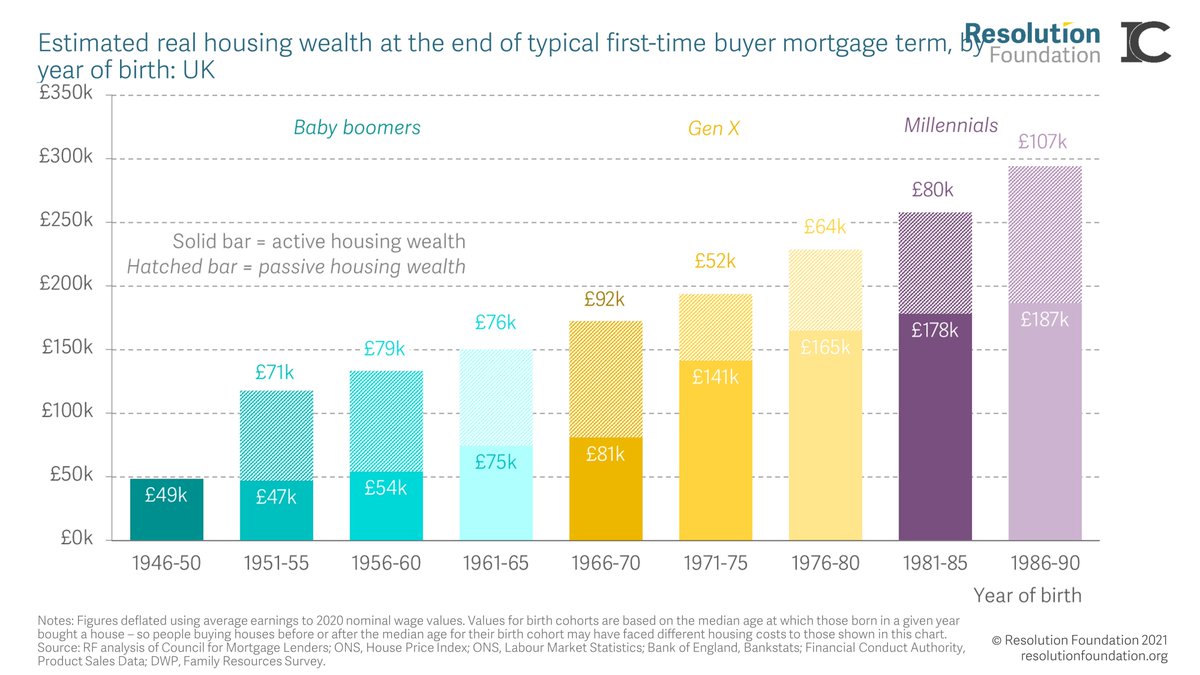

Of course, a paid-off mortgage is also money saved. But today’s first-time buyers do not look set to experience the windfall gains that older generations did when it comes to house price appreciation …

… so although they will end their first mortgage with more property wealth than any previous generation, far more of it will have been ‘active’ (i.e. saved) than ‘passive’ (i.e. the result of rampant house price growth).

Given these eye-watering figures, it’s not surprising young people today find it much harder than their parents’ and grandparents’ generation to get on the housing ladder. 55% of those born 1956-1960 were homeowners by the age of 30, compared to just 27% for those born 1981-1985

Here’s one reason why. A family headed by someone born in the early 1970s, with typical family income levels, would have saved enough for a first-time deposit by the age of 22. It will take a family headed by someone born in 2002 up to their 36th birthday to save for a deposit.

All-in-all, home ownership is increasingly the preserve of the better off. In 1996, the typical first-time buyer family had an income that put them at the 38th percentile of the income distribution of their age group; by 2020 they stand at the 48th percentile.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh