Huy Fong's Sriracha hit revenue of $150m+ a year...with no sales team, no trademark and $0 in ad spend.

Its creator is Vietnamese-American David Tran, making the sauce's success a tale of immigrant hustle and a product that literally sells itself.

Here's the story🧵

Its creator is Vietnamese-American David Tran, making the sauce's success a tale of immigrant hustle and a product that literally sells itself.

Here's the story🧵

1/ The Sriracha story traces back to the 1930s.

In a Thai town called Sri Racha, a housewife named Thanom Chakkapak created a paste of chili peppers, distilled vinegar, garlic, sugar and salt.

Variations of this recipe have travelled across the globes in the decades since.

In a Thai town called Sri Racha, a housewife named Thanom Chakkapak created a paste of chili peppers, distilled vinegar, garlic, sugar and salt.

Variations of this recipe have travelled across the globes in the decades since.

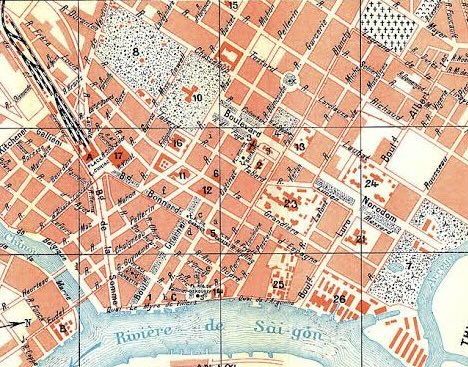

2/ One variation was created by David Tran, a major in the South Vietnamese army.

In 1978, the Tran family joined 3k+ refugees and fled Communist Vietnam on a Taiwanese boat called the Huey Fong (means "Gathering Prosperity”). The boat inspired the business name Huy Fong Foods.

In 1978, the Tran family joined 3k+ refugees and fled Communist Vietnam on a Taiwanese boat called the Huey Fong (means "Gathering Prosperity”). The boat inspired the business name Huy Fong Foods.

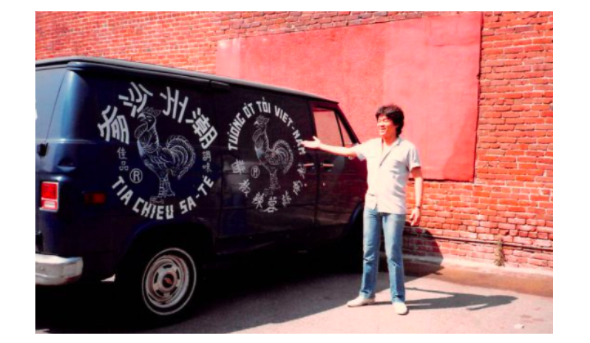

3/ Tran landed in the US and ended up in LA.

At the time, Sriracha was absent from California. So Tran brought his recipe, swapping out chilis for a local ingredient: jalapeños.

He filled recycled baby jars and sold product out of a Blue Chevy Van, making $2.3k the first month.

At the time, Sriracha was absent from California. So Tran brought his recipe, swapping out chilis for a local ingredient: jalapeños.

He filled recycled baby jars and sold product out of a Blue Chevy Van, making $2.3k the first month.

4/ To really make the product stand out, Tran slapped a Rooster logo on everything he sold.

Why? He was born in 1945: The Year of the Rooster.

He would later design the famous squeeze bottle and added a green cap as a sign of "freshness".

Why? He was born in 1945: The Year of the Rooster.

He would later design the famous squeeze bottle and added a green cap as a sign of "freshness".

5/ The sauce's popularity took off in the early-1980s among Asian restaurants and grocers. He kept upgrading manufacturing to meet demand:

◻️ 1980: a 5k sq ft building in Chinatown LA

◻️ 1987: a 68k sq ft warehouse in Rosemand, CA

◻️ 2010: a 650k sq ft warehouse in Irwindale, CA

◻️ 1980: a 5k sq ft building in Chinatown LA

◻️ 1987: a 68k sq ft warehouse in Rosemand, CA

◻️ 2010: a 650k sq ft warehouse in Irwindale, CA

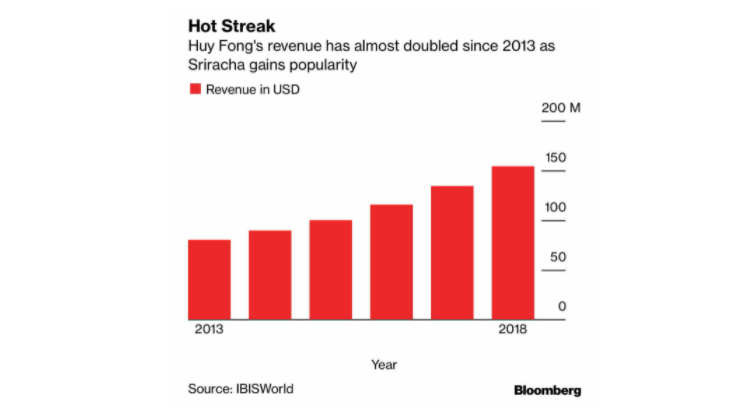

6/ Sriracha's success has come with:

◻️ No sales team (Tran has mostly maintained the same 10 distributors and wholesale pricing from the 80s)

◻️ No ads (Sriracha's cult-like status comes from "word of mouth")

In 2019, sales hit $150m (10% of the US hot sauce market).

◻️ No sales team (Tran has mostly maintained the same 10 distributors and wholesale pricing from the 80s)

◻️ No ads (Sriracha's cult-like status comes from "word of mouth")

In 2019, sales hit $150m (10% of the US hot sauce market).

7/ With so few ingredients, Tran prioritizes the best ones to win the market.

Timing fresh jalapeños is tough: the ripening window (green to red) leaves no room for error.

Due to the harvesting seasons, Huy Fong may make a whole year's supply of Sriracha in a 10-week span.

Timing fresh jalapeños is tough: the ripening window (green to red) leaves no room for error.

Due to the harvesting seasons, Huy Fong may make a whole year's supply of Sriracha in a 10-week span.

8/ For 28 years, Huy Fong was able to maintain its exacting quality standards with one exclusive jalapeño supplier.

In 2017, the partners had a falling out. Huy Fong now sources from 3 suppliers.

Its factory runs 16hrs a day and it goes through 100m pounds of chilis a year.

In 2017, the partners had a falling out. Huy Fong now sources from 3 suppliers.

Its factory runs 16hrs a day and it goes through 100m pounds of chilis a year.

9/ Interestingly, Tran never trademarked "Sriracha" (he did trademark the green cap and rooster, though).

This is the reason why so many competing brands -- from Heinz to Tabasco -- have a "Sriracha" sauce.

This is the reason why so many competing brands -- from Heinz to Tabasco -- have a "Sriracha" sauce.

10/ Tran doesn't care about competitors:

"I never worry about [other brands] because we're too busy making it. I can't make enough of my product to meet the demand, so let them have it and work together for the consumer."

Or brands using the name:

"It's free advertising."

"I never worry about [other brands] because we're too busy making it. I can't make enough of my product to meet the demand, so let them have it and work together for the consumer."

Or brands using the name:

"It's free advertising."

11/ One competitor is back in Thailand: The Winyarat family purchased the original recipe in 1984 and creates "Sriraja Panich".

It uses Thai cayenne peppers instead of jalapeños but has struggled to make in-roads in the US.

It uses Thai cayenne peppers instead of jalapeños but has struggled to make in-roads in the US.

12/ The universal appeal of Huy Fong's Sriracha is encoded in the label, which includes 5 languages.

In the US, the sauce has clearly achieved cult status (and was even named Bon Appetit's "Ingredient of the Year" in 2009).

In the US, the sauce has clearly achieved cult status (and was even named Bon Appetit's "Ingredient of the Year" in 2009).

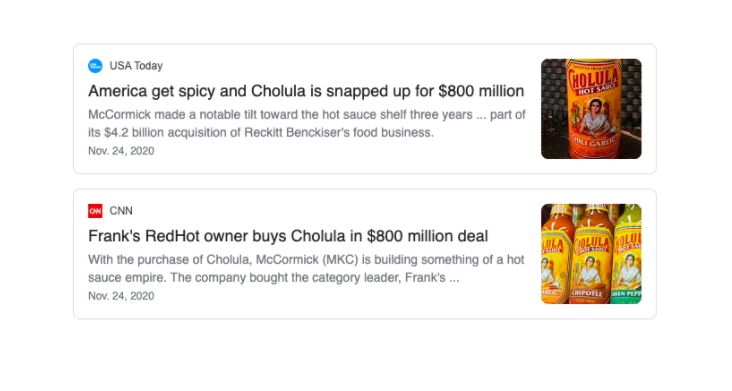

13/ Investors have been knocking on Tran's door for decades.

In November 2020, Choulala hot sauce was acquired by spicemaker giant McCormick & Co. for $800m (on $92m sales).

A similar price / sales multiple (~9x) for Huy Fong easily nets a $1B+ valuation.

In November 2020, Choulala hot sauce was acquired by spicemaker giant McCormick & Co. for $800m (on $92m sales).

A similar price / sales multiple (~9x) for Huy Fong easily nets a $1B+ valuation.

14/ Tran doesn't need the money. His motto is "a rich man's sauce at a poor man's price" (he caps retailer selling price <$10).

"My American Dream was never to become a billionaire. We started this b/c we like fresh, spicy chili sauce.”

His children will keep the legacy going.

"My American Dream was never to become a billionaire. We started this b/c we like fresh, spicy chili sauce.”

His children will keep the legacy going.

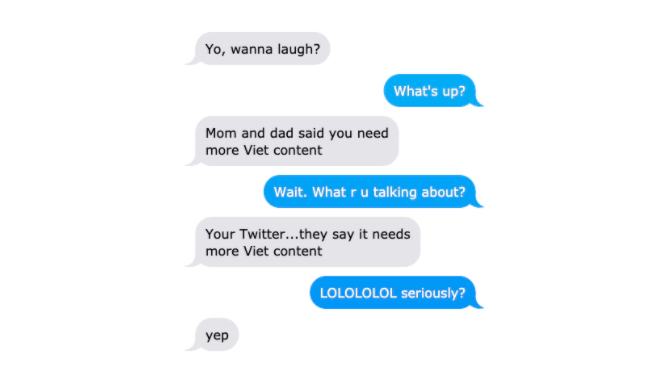

15/ Follow @TrungTPhan for other glorious business stories.

PS. I wrote this thread because my parents told my sister I need more "Viet" content.

PS. I wrote this thread because my parents told my sister I need more "Viet" content.

16/ Sources

Whale Bone Mag: whalebonemag.com/sriracha-panic…

Bloomberg: bloomberg.com/news/features/…

TIFO:todayifoundout.com/index.php/2017…

"Siracha" Doc: srirachamovie.com

Whale Bone Mag: whalebonemag.com/sriracha-panic…

Bloomberg: bloomberg.com/news/features/…

TIFO:todayifoundout.com/index.php/2017…

"Siracha" Doc: srirachamovie.com

17/ POSTSCRIPT

Here’s another Viet story for you, my great-grandfather was Vietnam’s leading nationalist at the turn of the 19th century and also sported a legendary beard: en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phan_B%E1…

Here’s another Viet story for you, my great-grandfather was Vietnam’s leading nationalist at the turn of the 19th century and also sported a legendary beard: en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phan_B%E1…

18/ Live footage of me with this thread popping

https://twitter.com/TrungTPhan/status/1408779694862897159?s=20

19/ FINAL NOTE: When Huy Fong moved to Irwindale, the City of filed a lawsuit alleging that the sauce-making released "odors and eye-watering airborne irritants".

A judge threw out the case in 2014 and now Huy Fong lets people tour the factory to judge for themselves.

A judge threw out the case in 2014 and now Huy Fong lets people tour the factory to judge for themselves.

20/ We are def talking about Sriracha on the next episode of the Not Investment Advice (NIA) podcast.

Throw me all your questions ("Is it OK to drink Sriracha?") and I'll answer them:

🔗open.spotify.com/show/0Pogh5lcy…

Throw me all your questions ("Is it OK to drink Sriracha?") and I'll answer them:

🔗open.spotify.com/show/0Pogh5lcy…

21/ We did it folks. This Siracha thread hit the top of Hacker News today.

Next on my bucket list: American Ninja Warrior.

Next on my bucket list: American Ninja Warrior.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh