In the summer of 1695, British pirates committed a terrible series of crimes off the coast of Western India—acts that led to the first global manhunt and one of history's great disappearing acts. Three centuries later, new clues are emerging about what actually happened. (Thread)

(Some of what follows is told at greater length in my book Enemy of All Mankind: A True Story of Piracy, Power, and History's First Global Manhunt, now out in paperback.) penguinrandomhouse.com/books/545158/e…

It’s the last decade of the 17th century. The world is transforming into a new interconnected system of trade and information networks. In London, history’s first joint-stock corporation—The East India Company—is making a fortune importing calico and chintz fabrics from India.

The East India Company is the future of wealth accumulation, but an older model is behind the fortune of the world’s wealthiest man: India’s tyrannical emperor Aurangzeb, last of the Muslim Mughal dynasty.

The two economic models—dynastic, imperial wealth and publicly-traded corporation—are locked in an uneasy alliance, but the East India Company has been struggling at home after a series of financial scandals.

In 1694, an obscure British sailor generally known as Henry Every leads a mutiny in a Spanish port, and absconds with a small crew and a state-of-the-art new vessel, a ship so fast in the water that one observer notes “she fears not who follows her.”

Rechristening the ship The Fancy, Captain Every leads the men on a daring voyage around the Horn of Africa, all the way to the mouth of the Red Sea, where they lie in wait for Indian treasure ships returning from Mecca.

Eventually they launch a seemingly reckless attack on a massive vessel known as the Ganj-i-Sawai, loaded with both treasure and religious pilgrims, many of them women belonging to Aurangzeb’s royal court.

After a highly unlikely series of events—a cannon explodes on the Indian ship just as Every lands a cannonball directly on the ship’s main mast—the pirates from the Fancy storm the Ganj-i-Sawai.

The pirates escape with one of the most lucrative hauls in the history of crime, perhaps as much as $100M in Arabian gold and other treasure. And they commit devastating acts of sexual violence, raping many of the women on the ship.

Enraged by the crimes of the British pirates, Aurangzeb imprisons the representatives of the East India Company in Bombay and Surat, and threatens to evict the entire organization from India.

It’s an existential crisis for the world’s first public corporation. Losing the monopoly on trade with India will send them into bankruptcy. (And likely change the future course of history, given that the EIC will ultimately be the foundation of the British empire in India.)

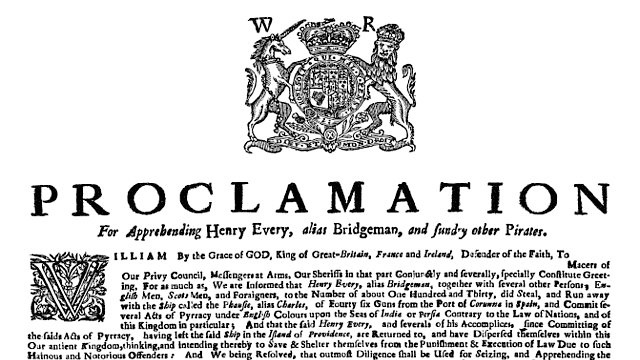

In partnership with the Crown, the EIC help fund and oversee a massive manhunt for Every and his crew, hoping to bring them to justice and to prove to Aurangzeb that England has no tolerance for piracy.

In Enemy Of All Mankind, I tell the story of that manhunt and the media frenzy around the trial that was ultimately staged in London; it’s basically a combination of the search for Bin Laden and the OJ trial all rolled into one.

But here’s the thing: Every and some of his crew manage to escape the manhunt. For a time, Every was the world’s most wanted man, and one of the most notorious people on the planet. And somehow he just… disappeared.

For hundreds of years, the trail went cold. And then in 2014, an amateur historian named Jim Bailey discovered a cache of colonial-era coins while exploring a fruit grove in Rhode Island with a metal detector.

smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/17t…

smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/17t…

One of coins was Arabian, minted in Yemen in 1693. Since then, more than a dozen similar coins have been found throughout New England. Bailey’s discovery suggests that Every might have settled in Rhode Island, instead of Ireland as had long been suspected.

Henry Every’s original actions marked one of the first points that a small band of criminals could trigger a crisis that reverberated around the world, a true-crime narrative that captured the imagination of people on multiple continents.

Those ancient coins that Jim Bailey unearthed in Rhode Island suggest that the story of Every and his legendary crimes may still have more chapters left in it.

For more, pick up a copy of Enemy of All Mankind, which is probably about as close as I will ever come to writing a summer beach-read thriller. bookshop.org/books/enemy-of…

According to the WSJ, it’s “thoroughly engrossing . . . a spirited, suspenseful, economically told tale whose pace never flags.”

amazon.com/Enemy-All-Mank…

amazon.com/Enemy-All-Mank…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh