I continue with the Italian Wars with the 1509 battle of Agnadello, a disaster for the Republic of Venice defeated by the mighty French army! Machiavelli famously said of this battle that in one day Venetians "lost what it had taken them eight hundred years' exertion to conquer."

The previous Italian War had ended in 1504 with peace between France and Spain but during those days peace would last very short in Italy! In the previous wars, France had already conquered the Duchy of Milan and Kingdom of Naples, which eventually ended in Spanish hands.

The Papal States also managed to expand with the army led by Cesare Borgia, the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI, but when his father died, he lost the favor of the papacy. The territories of the Papal States began collapsing and Venice took the opportunity to expand.

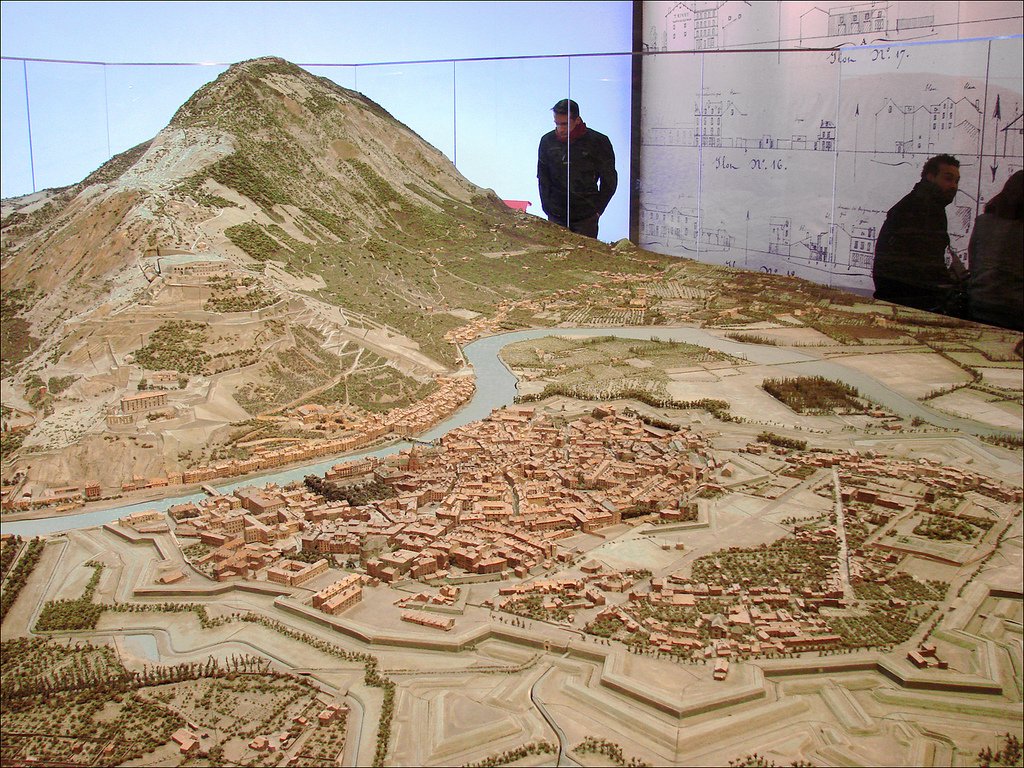

The Republic of Venice had already been expanding over the Italian mainland for the entire 15th century. This maritime merchant republic managed to carve out a large dominion of land territories, calling them Domini di Terraferma, opposed to Stato da Màr (maritime territories).

With Duchy of Milan under French rule, Kingdom of Naples under the Spanish and Papal States crumbling, Republic of Venice was now by far the strongest independent Italian state. This also made Venice the biggest target of foreign powers, hungry for more conquests in Italy.

At the time Venice was still a wealthy mercantile superpower in the Mediterranean, trading in Levant, getting spices through Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo. The maritime wealth made Venice hungry for more, expanding into neighboring lands as well, but this also brought many enemies!

Pope Julius II tried to exploit this situation and encouraged foreign powers to take on Venice. He first convinced the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I to attack in 1507, but his campaign was poorly led and turned into a fiasco, ending with loss of his own territory to Venetians!

Pope Julius II didn't give up and in 1508 he managed to form a huge anti-Venice coalition called the League of Cambrai consisting of France, Spain and Holy Roman Empire, and of course the Papal States. The goal of this coalition was to divide the mainland territories of Venice!

French were the most eager to fight and in 1509 king Louis XII was able to once again assemble a mighty army, stronger than ever. Next to around 7500 Swiss mercenaries were recruited after very difficult negotiations, he also had his own infantry and Landsknechts to back it up.

The French also had around 2500 heavy cavalry knights. Louis XII did not trust Emperor Maximilian I. to keep his promise and despite the official alliance, he was ready for a war with everybody, read to take Italy over by himself. The French headed towards Venetian territory!

The Venetians were well prepared and confident after their success against the Holy Roman Empire. They were lead by the capable Orsini cousins, Bartolomeo d'Alviano and Niccolò di Pitigliano. Both of them very fine men, but in this case, the split command would prove disastrous!

The problem was that the Venetian commanders d'Alviano (left pic) and Pitigliano (right) supported two entirely different strategies. Pitigliano wanted to wage a defensive war and avoid pitched battles at all costs, while d'Alviano wanted to attack and take the war to the French.

Looking back, it seems that both strategies could have worked if the Venetians fully committed to them, but having the army split with one force doing one thing and the other something completely different was the worst possible approach! It would lead to disaster of Agnadello.

The French crossed the river Adda unopposed due to the Venetian overall defensive strategy, but then d'Alviano decided to go on offensive and clashed with the French advance guard commanded by the experienced Italian condottiere in service of France Gian Giacomo Trivulzio.

The battle with the French went well for Venice, and the Venetian infantry was well positioned in a defensive position behind a dry canal bed, with cavalry just far enough from French artillery range. Led by Saccoccio da Spoleto the infantry adopted aggressive approach as well.

Instead of waiting for the French to come in range for Venetian artillery, the infantry regiments crossed the canal to attack French artillery, but were flanked by the French heavy cavalry. Fierce fighting broke out and d'Alviano arrived to help the Venetians.

The Venetians were winning the fight, but more French reinforcements would arrive, as Louis XII ordered 500 fresh knights to help regroup the cavalry and lead the counterattack. Meanwhile Pitigliano refused to send Venetian reinforcements, sticking to his defensive-minded plan.

The French cavalry attacks on the overwhelmed d'Alviano's forces and infantry were lethal and they soon crushed the Venetians, routing them and many of them were cut down, filling the Italian fields with corpses. It is said that more than 10000 of 15000 Venetians who fought died!

The mighty 30000 French army did not have any substantial losses and continued to march forward. They also captured the gallant Venetian commanded d'Alviano who risked everything with his strategy and also lost everything for his republic of Venice!

Despite around 15000 fresh Venetian soldiers who did not engage left, the news of this battle was so demoralizing that the Venetian army was falling apart quick, with many deserting and cities surrendering to French without a fight one by one. Venice was furious with commanders!

D'Alviano was too brave and Pitigliano too conservative. An uncoordinated mixture of two strategies turned out to be a total disaster and it cost Venice almost entire Terraferma territory in the mainland in just one day, 15 April 1509, the day of the defeat at Agnadello!

But the craziest part of this war was that even such disaster didn't mean the end of Venice. The alliances would soon change and with them also the fortunes of war. Pope Julius II realized that with Venice diminished he had weakened Italy too much. He turned anti-French.

The former territories of Venice that would come under French and Imperial rule also resented their new masters soon, especially the peasants, and discontent was growing. In the next Years, Venice would reclaim a lot of it back, but I will leave that for the next part!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh