The battle of La Motta was another significant battle of the Italian Wars, fought on 7 October 1513 between Republic of Venice and combined forces of Spain and Holy Roman Empire. Venice lost yet another battle, but its enemies were once again unable to take advantage of victory!

Another battle that happened during the War of the League of Cambrai (1508-1516), a particularly bloody episode during the Italian Wars where territory of Venice was often contested. Venetian forces were already crushed in 1509 at the battle of Agnadello, but had recovered.

Despite defeat, Venice was able to restore its possessions in the Italian Mainlands, the Terrafirma. Meanwhile the forces of the anti-Venetian League of Cambrai were busy fighting each other. In 1513, Venitians would ally with the French who had previously crushed them in 1509.

This was just another example how volatile and unpredictable the Italians Wars were. As part of alliance, the French released Venetian commander Bartolomeo d'Alviano whom they imprisoned at Agnadello. D'Alviano would now have to lead Venetian army against Spanish and Imperials.

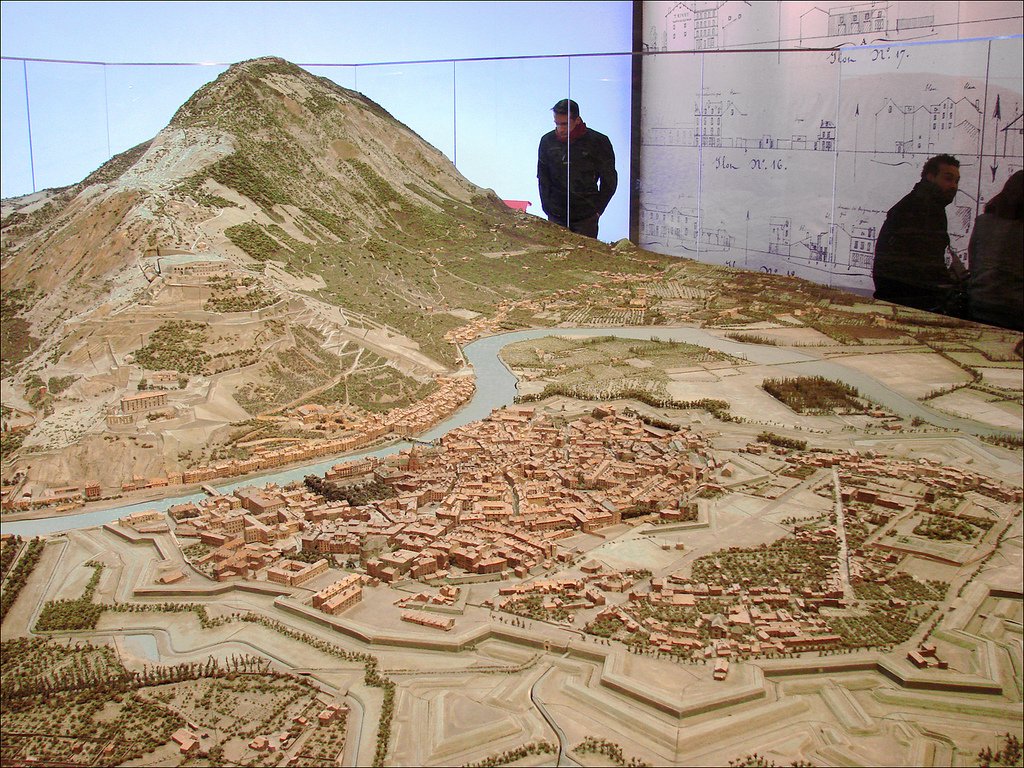

The French invaded Italy but suffered a humiliating loss by the Swiss at Novara in June of 1513 and were routed back. Venice was now on its own and facing an invasion of combined Spanish and Imperial forces. D'Alviano retreated to Padua and was besieged there in August.

The combined army decided to lift the siege and plundered the Venetian lands instead in hopes of provoking D'Alviano to come out of Padua and face them on the open field. For entire September the Spanish and ferocious German Landsknecht mercenaries looted Venetian Terrafirma!

The pillaging was brutal and was also specifically designed to have a psychological effect as they burned down the villas of Venetian nobles to humiliate them! They even came close to Venice and fired some taunting shots with canons! D'Alviano fell for the provocation and moved.

The armies would meet on 7 October near Vicenza. The Venetians brought more men and a better more experienced cavalry, but regarding the quality of infantry the Spanish-Imperial side had a big advantage, the core of its troops being hardened Spanish and Landksnecht veterans.

D'Alviano commanded around 3000 cavalry. The 10000 Venetian infantry he brought were mostly city militias. Meanwhile the Spanish had only 1000 light cavalry, 4000 Spanish infantrymen and 3500 Imperial Landsknechts. Both sides had an impressive number of guns and artillery.

The Spanish-Imperial army was commanded by Ramon de Cordona, a rather mediocre commander who had lost to French at Ravenna a year earlier, but the infantry contingents were commanded by two capable and charismatic men Georg von Frundsberg and Fernando d'Ávalos of Pescara.

Frundsberg and Pescara understood the new pike and shot warfare and this battle would once again prove the importance of this infantry-based tactic that the Venetians had not yet mastered. Their leader D'Alviano used a much more cavalry-heavy tactic and tried to outflank the foe.

The Venetians started the battle well with their superior cavalry pushing the Spanish cavalry back, but when the two infantry forces clashed, the Spanish and the Landsknecht formations stood firm against the larger Venetian infantry which collapsed and was routed.

After the collapse of the Venetian infantry, their cavalry began to rout in panic as well. The battle was won by the Spanish and Imperial forces! The Landsknechts in particular were relentless in killing the fleeing Venetian infantry as they had scores to settle with hated Venice

The result was a total disaster for Venetians, losing around 5000 men in chaos that ensued. Many cavalrymen drowned trying to cross nearby rivers, while the commander of Vicenza didn't let the fleeing Venetian infantry in, afraid that the pursuers might enter with them!

The Spanish and Imperials then captured Vicenza but despite their big victory, they were not able to take any crucial advantage of it. D'Alviano escaped and would not take risks anymore. The combined Spanish-Imperial army continue to pillage, but could not hold the territories.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh