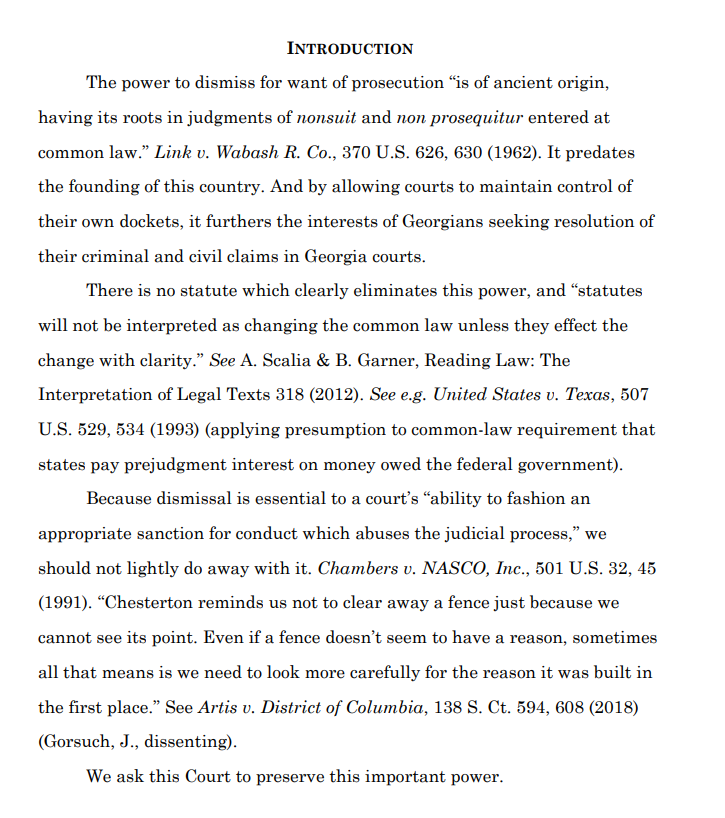

I had a lot of fun writing this amicus brief for the Georgia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers explaining why trial courts have always had the power to dismiss cases for want of prosecution, even when the litigant dragging his heels has a badge. /1

efile.gasupreme.us/viewFiling?fil…

efile.gasupreme.us/viewFiling?fil…

To summarize: EVERY state agrees that trial courts have the inherent power to dismiss cases for want of prosecution.

The only split is whether that rule applies to the state. And the states that disallow the practice often do so for policy reason.

/2

The only split is whether that rule applies to the state. And the states that disallow the practice often do so for policy reason.

/2

There IS one Texas case that many courts have come to rely on, though, State v. Anderson, which DID go into some old common law rules to find that only prosecutors may issue a nolle prosequi.

But it dealt with a case where a judge found res judicata based on acquittals. /3

But it dealt with a case where a judge found res judicata based on acquittals. /3

Which, of course, the US Supreme Court would later okay in cases like Ashe v. Swenson and Yeager.

To summarize GACDL's argument: "if it's not broke, don't fix it."

/4

To summarize GACDL's argument: "if it's not broke, don't fix it."

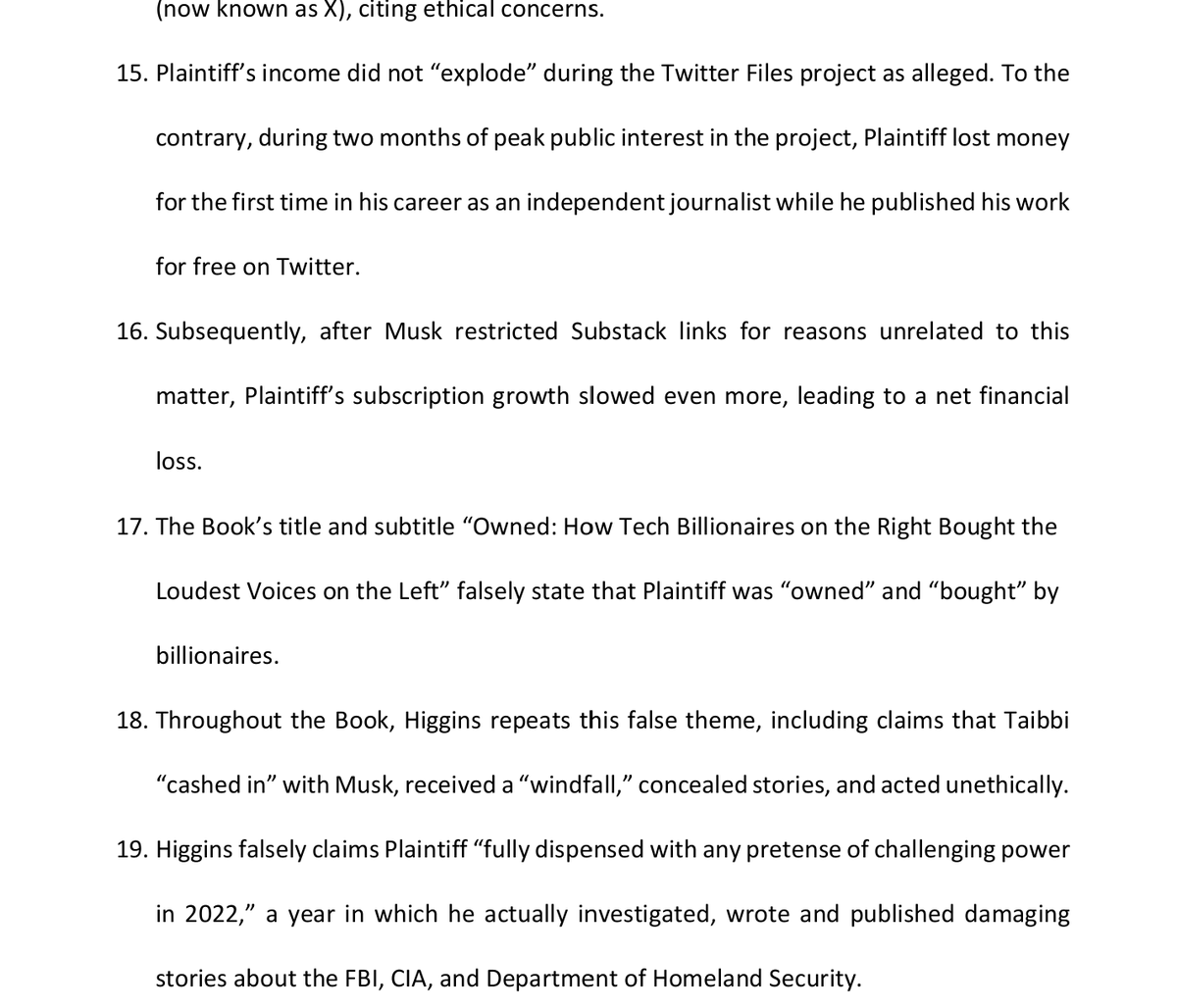

/4

It's my hope that trial courts will continue to have the power to dismiss a prosecutor's case, without prejudice, if he insists on repeatedly showing up to court unprepared.

/f

/f

Oh, one last point, a lot of the filings in this case claim that the first time any Georgia court mentioning dismissal for want of prosecution in a criminal case was 1978. Not so. The earliest I could find was 1904.

Herring v. State, 119 Ga. 709, 719, 46 S.E. 876, 881 (1904)

Herring v. State, 119 Ga. 709, 719, 46 S.E. 876, 881 (1904)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh