Did you know that the invention and spread of writing in Ancient Mesopotamia and the surrounding areas coincided with, and perhaps caused, dramatic changes in the visual art of the region? 🧵

By the time writing appeared, 3500–3300 B.C., visual art had existed in the area for millennia. In 2 Anatolian caves, engravings and carvings have been found dating to 15 000 BCE. Idk when the face is from, but it's also in one of those caves and too cool not to include.

We know of much more art from the Neolithic period.

Dated to 9000 BCE and afterwards, we have paintings, carvings, and statues spanning from 'Ain Ghazal in modern day Jordan

Dated to 9000 BCE and afterwards, we have paintings, carvings, and statues spanning from 'Ain Ghazal in modern day Jordan

One famous site for preliterate art in the region is the proto-city of Çatalhöyük, 7100 - 5700 BCE. Proto-cities are large Neolithic towns that lack planning and centralized rule. Çatalhöyük appears to also have lacked social stratification.

However, to say that writing appeared in 3500–3300 B.C. is a simplification, since it has a long prehistory. Before we can talk about the intersection between writing and art, we have to go over the development of writing.

For centuries, once mythical explanations fell out of favor, it was thought that writing had developed linearly, from concrete, literal pictures to pictographs to more abstract ideographs, whose meaning came only from convention, not representation.

Eventually these ideographs evolved to represent the sound of words, not just their meaning, what's called phoneticism.

However, more sophisticated archaeology soon challenged this view.

In the late 19th/early 20th century, excavations began and Jemdet Nasr and Susa.

However, more sophisticated archaeology soon challenged this view.

In the late 19th/early 20th century, excavations began and Jemdet Nasr and Susa.

They found convex clay tablets with markings on them. They listed about 1500 different signs, and the majority of them seemed pretty abstract already. It seemed like they had uncovered an already quite complex writing system, even though it was some of the oldest writing found.

Hundreds of tablets uncovered at Uruk starting in 1929 also seemed to contradict the pictographic theory. These tablets were even older and also had scarce pictorial signs. The oldest "writing" consisted of wedges, circles, ovals, and triangles, seemingly not pictorial.

Interestingly, the first documents uncovered at Uruk are from 200 years after the emergence of cities and the temple institution in the area. Scholars had previously assumed writing was necessary for state formation.

These questions, and more, remained open for decades. Then in 1959, the renowned assyriologist A. Leo Oppenheim wrote an article called "On An Operational Device in Mesopotamian Bureaucracy."

It sounds boring, but this article would lead to a new theory of writing's beginning.

It sounds boring, but this article would lead to a new theory of writing's beginning.

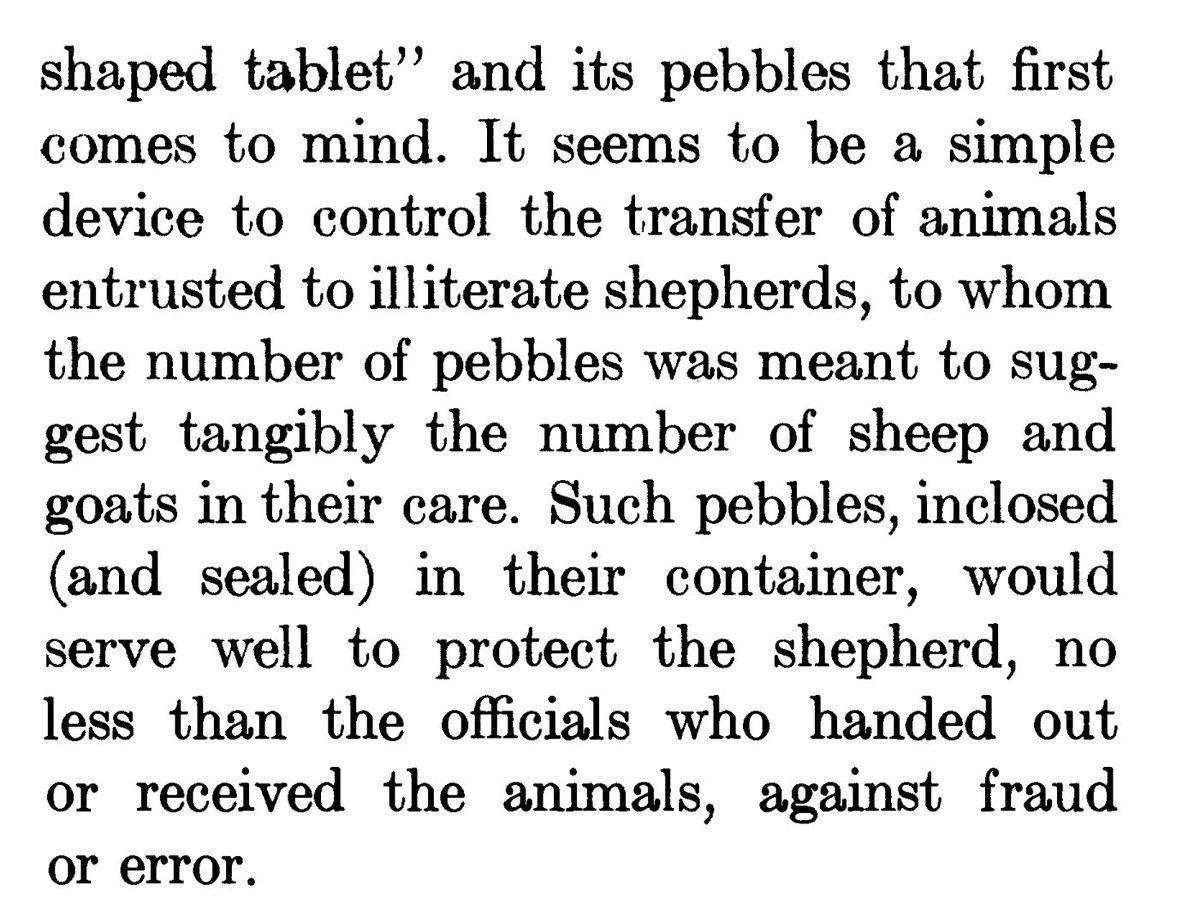

The article was focused on a hollow clay tablet, shaped like an egg. It was found in an excavation of the ancient city of Nuzi, modern day Iraq, in the 1920s.

The documents from the expedition said that within the hollow tablet were 48 small stones, called "pebbles." Oppenheim added up the animals listed on the outside of the tablet, and found that they summed to 48! Clearly, not a coincidence.

But, unfortunately, the pebbles were nowhere to be found in 1959, not carefully recorded because nobody thought they were important.

Luckily, a man named Pierre Amiet read Oppenheim's paper.

Luckily, a man named Pierre Amiet read Oppenheim's paper.

Amiet studied seals from Mesopotamia, and worked as a conservator at Le Louvre, in the Department of Near Eastern Antiquities. He noticed a similarity between the hollow tablet at Nuzi and hollow tablets found at Susa. Connecting these two things was a bold move, since the

tablets in Susa were 2000 years older than the one found in Nuzi. This meant that some of the hollow tablets predated writing! And, luckily, this time, the "pebbles" or counters were kept alongside the hollow tablets.

Amiet even suggested a connection to writing: "One might ask whether [the scribe] had in mind the little objects that were enclosed in the envelopes, and that very conventionally would symbolize certain goods."

Then along comes the researcher Denise Schmandt-Besserat, in 1969, who was studying how people used clay in the Middle East. This study lead to her going to visit every museum that had a collection of clay objects from the middle east from 8000 to 5000 BCE.

She was expecting to find things like bowls and stuff, but something surprised her. There were a whole bunch of artefacts that weren’t mentioned in publications, so she wasn’t expecting them. You guessed it, she found a ton of these small counters, which she called tokens.

However, unlike the later examples, they weren’t enclosed in a hollow ball or a hollow tablet, they were just out in the open.

In 1970, Schmandt-Besserat read Amiet's article from 1966, and everything fell into place. She realized the connection between the loose, Neolithic tokens and the ones from Susa, thousands of years later.

This sent her on a decades-long quest to uncover the relationship between these tokens and the beginning of writing. She found two crazy things:

1) the timespan: it seems like these tokens were used continuously, although sometimes loose and sometimes not, from 8000-3000 BCE.

1) the timespan: it seems like these tokens were used continuously, although sometimes loose and sometimes not, from 8000-3000 BCE.

And 2) the immense geographical distribution of the token use. One economic culture, roughly speaking, took up the area within the rectangle, for thousands of years.

She spent painstaking years cataloguing and analyzing all the different types of tokens. The different shapes corresponded to different goods or different amounts. She also saw similarities between the first written characters and the shapes of the tokens when impressed on clay.

There's a lot more to talk about here, but I want to get to how it relates to art. What Schmandt-Besserat found was that writing developed in a ~4000 year long process.

The basic trajectory is tokens -> envelopes that held tokens -> envelopes with impressions that held tokens, with personalized seals -> tablets with impressions -> tablets with symbols based upon those impressions -> cuneiform writing system.

Around 3100 BCE, impressions were replaced by incisions, cut into the tablet with something called a reed stylus, allowing for more intricate signs. This soon led to cuneiform proper, not proto-cuneiform.

So.....how does this relate to the art of the time?

Later in her career, Denise Schmandt-Besserat focusing on the art of the region as well. She found that art and writing were perhaps influencing each other, first writing influencing art, then art influencing writing.

She looked at three kinds of art that were as widespread as the tokens: pottery paintings, seals, and wall/floor paintings.

Let's focus on pottery painting first. Pottery painting became popular in Mesopotamia during the seventh millennium BCE. Then, weirdly, during the age of impressed texts, from 3500-2900 BCE, painted pottery vanished for some reason, as far as we can tell from the archaeological

Preliterate pottery consists of patterns, either geometric, or repeated animal or human figures. It seems like the goal was to cover the whole surface. Often lines were used to separate different designs from each other.

You might assume that the patterns and figures were just art for art's sake, to make the pottery look pretty. But most experts think that the images were meaningful, the animals, humans, and geometries symbolizing things or evoking myths.

Evocation is key. Preliterate pottery and art in general, only evoke ideas and myths, it never tells a myth or explicates an idea.

Writing, Schmandt-Besserat argued, led to narrative in art. Only after writing could visual art tell a story, rather than just evoke one.

Writing, Schmandt-Besserat argued, led to narrative in art. Only after writing could visual art tell a story, rather than just evoke one.

To tease out what is meant here, let's compare the preliterate pottery on the left to the literate pottery on the right.

In preliterate pottery, all examples of a "kind" (eg. dancers or cows) are identical, down to their stance. But literate pottery gives more individuality to each figure. Often status symbols are clearly drawn, or important figures are larger than unimportant ones.

They might look less "individual" to the untrained eye, but Schmandt-Besserat sees the distinctness clearly:

"Whereas preliterate painters tried hard to achieve the utmost stylization, those of the literate period aim to be as informative as possible."

"Whereas the preliterate pottery compositions formed an all-over pattern meant to be apprehended as a whole, or globally, those of the literate period were to be viewed analytically."

Something else important when showing narrative in a still image is showing that the figures share the same space. Let's take another look at that Çatalhöyük painting. Do you notice how all the humans have the same stance? Also, it's hard to tell how the humans are

relating to the deer and to each other. They're all somewhat evenly spaced apart, some above, some below, with nearly identical stances.

The easiest way to show that two figures are sharing the same space, instead of the two figures just being unrelated to each other and coincidentally being on the same wall, is something called a ground line.

In preliterate pottery, lines were mostly used to separate one design from another (left). But in literate pottery, we see ground lines. We know the ox and the people are sharing the same space, they are related, because they stand on the same ground.

Instead of figures just kinda floating around, we know that the artist wanted the viewer to see them as occupying the same space, standing on the same ground.

Literate art creates narrative by using space, like having a ground line, but also things like size (like, bigger figures are the more important ones), location (like, the focus of the narrative is in the center, minor characters to the side), differentiating individuals by

their clothes or accessories (to show status, for example, like drawing a crown on a king), showing the individuals gesturing, orientation of the individuals, things like that. An example of orientation creating narrative would be two individuals facing each other might show them

conversing, whereas two individuals facing same way might be showing them walking somewhere. How they’re oriented can show us how they’re interacting, in other words.

Schmandt-Besserat goes a lot deeper into the specifics. For instance, she suggests a link between determinatives and status symbols in visual art. Determinatives are words that modify nouns. It is what makes "every cat" mean something different than "any cat."

But in cuneiform, determinatives were often focused on specifying when two different words are spelled or pronounced the same. They're used to distinguish, to let the reader know which meaning or pronunciation to use.

One of the first determinatives in Mesopotamia was a star shaped sign. When this sign was placed next to a name, it meant that the name was referring to a god.

Schmandt-Besserat sees a similarity between the star shaped sign and the star shaped crowns here, on three of the figures, indicating that they're divine, while the other is a mortal.

Even if that one-to-one correspondence doesn't hold up, it's the idea of the determinative that's important, taken from writing and applied to art.

Controversially, she jumps from differences in artistic representation to differences in perception:

"...preliterate Near Eastern societies perceived the world circularly and all-inclusively, while literate cultures viewed it analytically and sequentially."

"...preliterate Near Eastern societies perceived the world circularly and all-inclusively, while literate cultures viewed it analytically and sequentially."

Anyways, this has gone on way too long. I'll end here with a picture of the famous Uruk vase, which nicely has both preliterate repetition and literate narrative. Let me know if you know anything more about this.

And keep in mind that, like with any grand, sweeping theory, there are criticisms of Schmandt-Besserat's conclusions. I'd love to know what archaeologists today think, if there's been any new developments.

Enter the thread portal:

https://twitter.com/DilettanteryPod/status/1408978347837714432

You can read some more thorough accounts of Schmandt-Besserat's theory of tokens here: en.finaly.org/index.php/The_…

and here: en.finaly.org/index.php?titl…

and here: en.finaly.org/index.php?titl…

and here: en.finaly.org/index.php?titl…

and here: en.finaly.org/index.php?titl…

My sources for this thread are mostly How Writing Came About (1997) and When Writing Met Art (2007) both by Denise Schmandt-Besserat. I didn't get into the second part of the latter book here, about how art influenced writing, it's also very interesting. Here's a snippet:

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh