Let me tell you the story of a book. Akedat Yitzhak was written by Isaac ben Moses Arama, who died in 1494. He lived in various places in Spain until the Jews were expelled in 1492, at which point he fled to Naples.

Naples is not far from Salonika, where the first edition of his commentary on the Bible was printed in 1522.

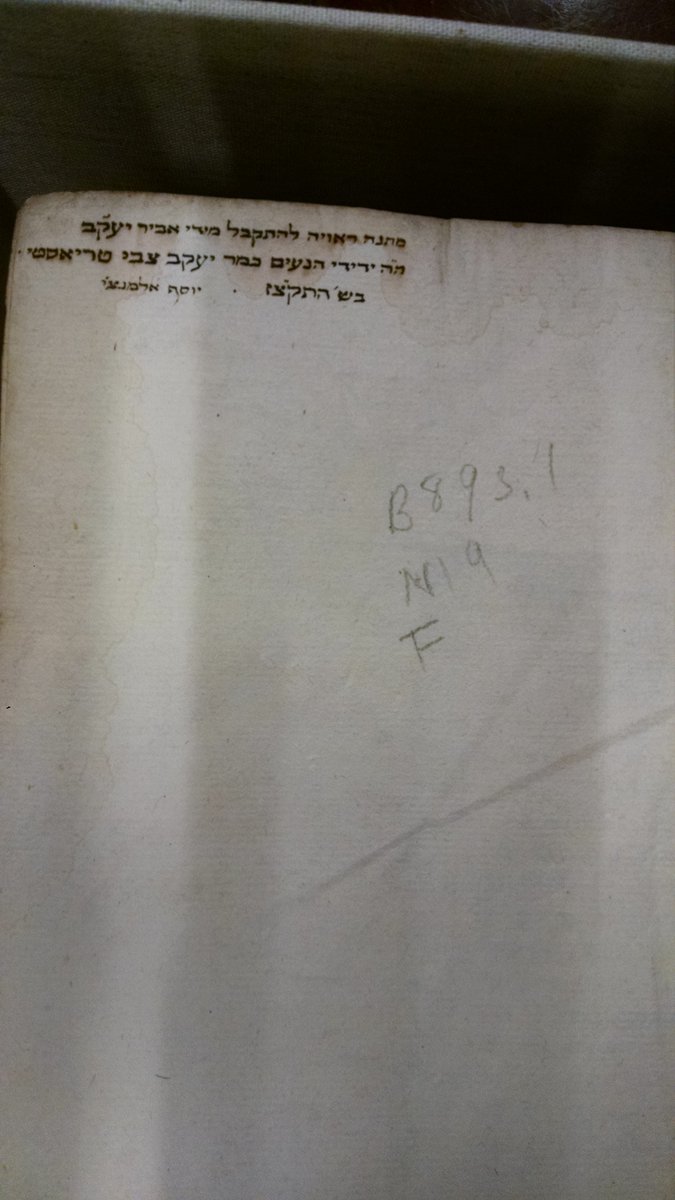

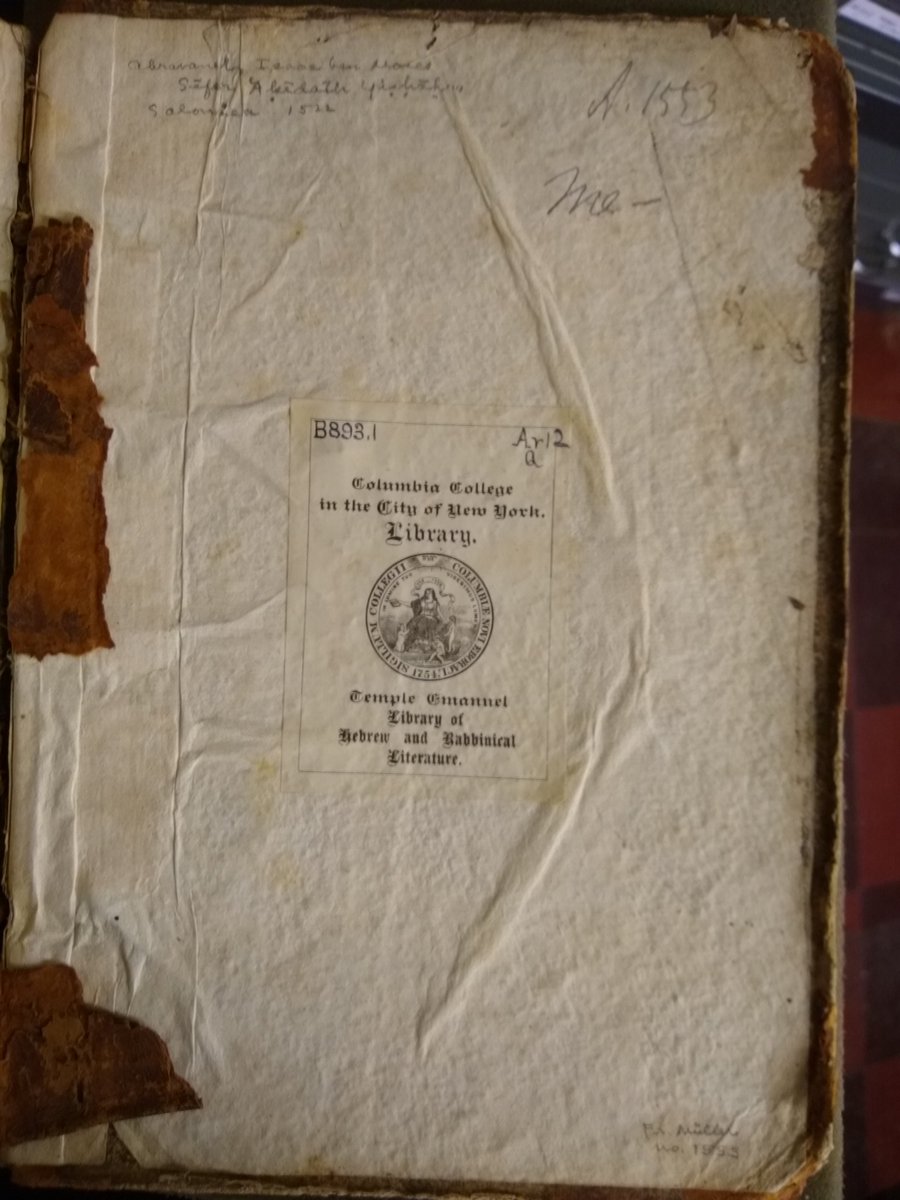

The call number for the copy @columbialib is B893.1 Ar12

clio.columbia.edu/catalog/113780…

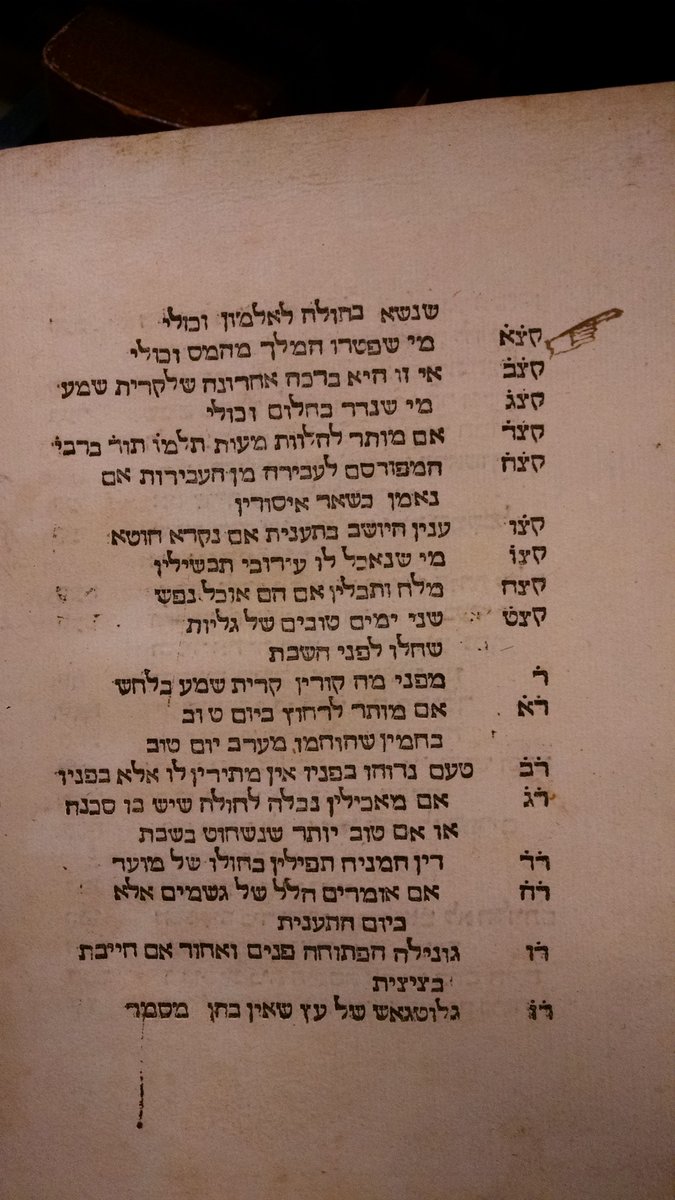

It is a worn copy, showing many signs of use (binding both volumes in one made it solid)

The call number for the copy @columbialib is B893.1 Ar12

clio.columbia.edu/catalog/113780…

It is a worn copy, showing many signs of use (binding both volumes in one made it solid)

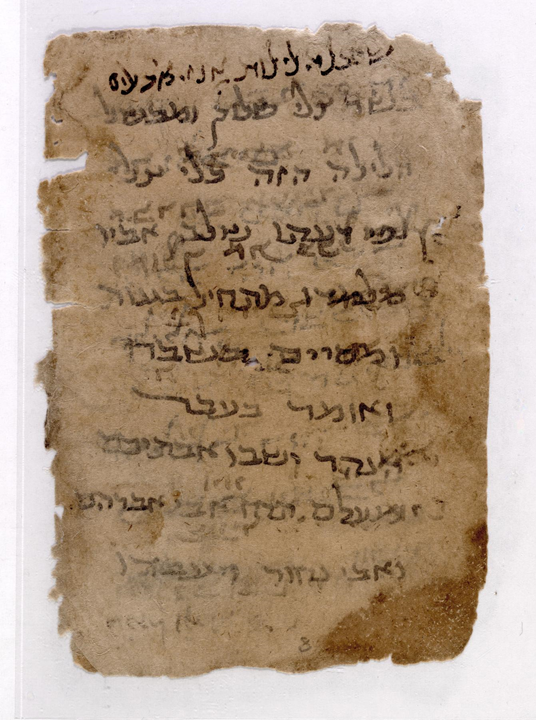

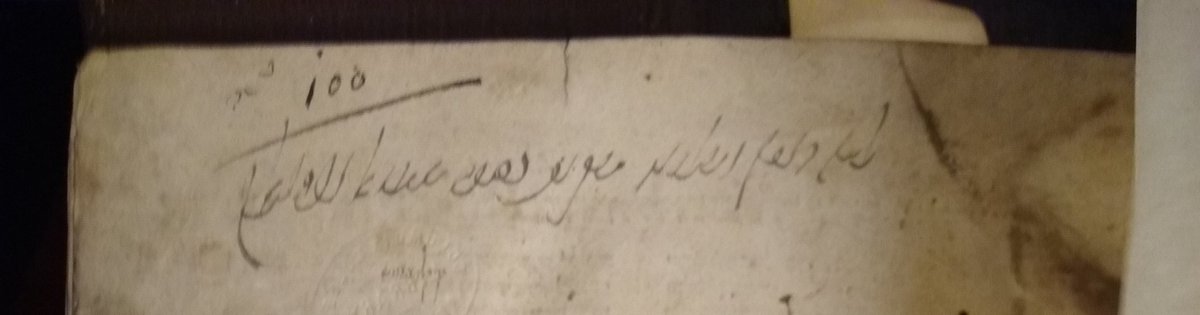

The opening flyleaf looks like it was owned by lots of people, but that's a bit misleading. All but the top and bottom inscriptions were written by Shelomoh (bar?) Shim'on, who bought it from Moshe (can't decipher the surname).

Note the phrase "lest someone come from the shuk"

Note the phrase "lest someone come from the shuk"

This was a fairly standard way to excuse writing one's name in a book (which you're not *really* supposed to do). But if you're worried about a random dude coming from the market and saying "that's my book," you're allowed to do it as a precaution.

Next up we have the two inscriptions in a Sephardic hand - I'm having trouble deciphering these, though.

And who's the one who put a cup of liquid on the sefer? (See previous pic of the full page.)

And who's the one who put a cup of liquid on the sefer? (See previous pic of the full page.)

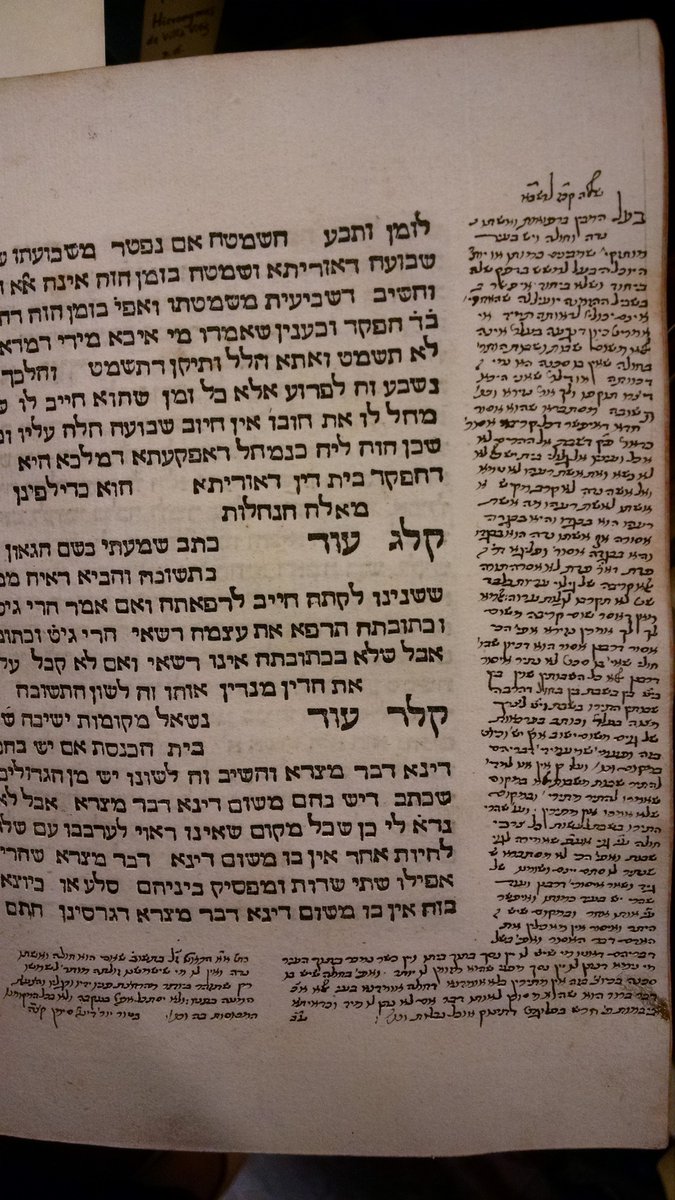

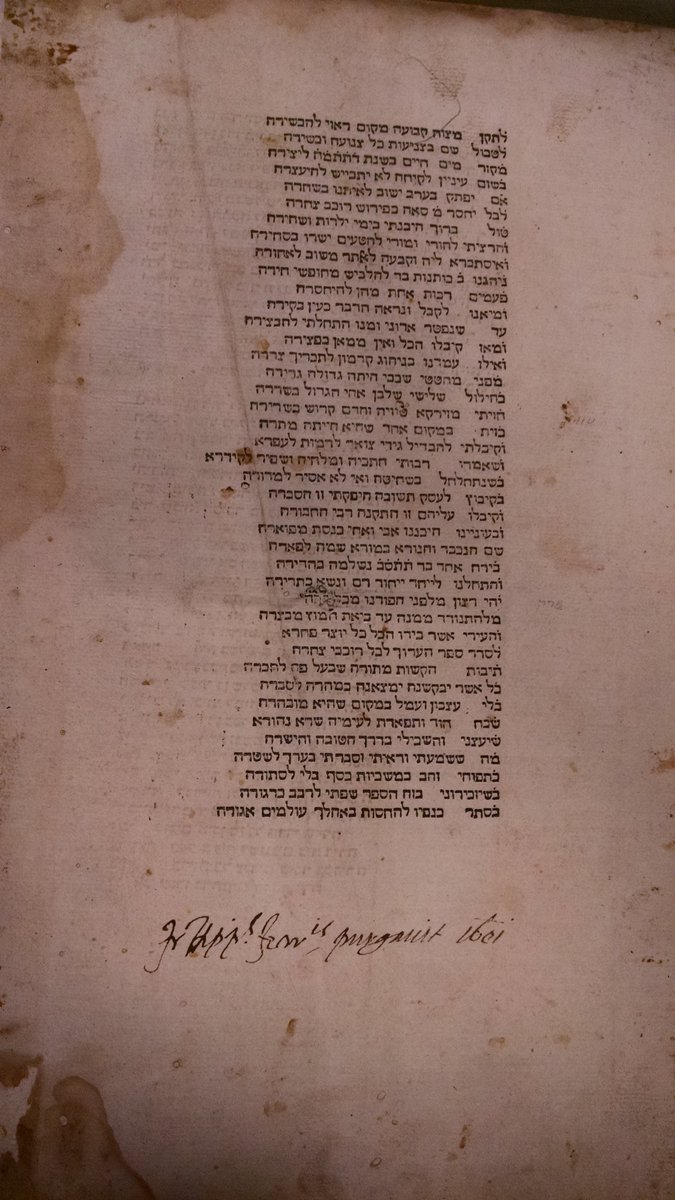

The next thing I do when looking for clues about the story of a book is too turn to the back to see if it was reviewed by censors. Sure enough...

1623 (I can't quite make him out, but I think that's Domenico Irosolomitano above) and (I think) Hippolite of Ferrara, 1618 or 28.

1623 (I can't quite make him out, but I think that's Domenico Irosolomitano above) and (I think) Hippolite of Ferrara, 1618 or 28.

Well, once I see censors, I have to check if they did anything. Sure enough...and unlike many, their ink didn't fade to highlight the text. In fact, it looks like it burned THROUGH the text.

(More on that note later; it happened to be tucked in on the same page.)

(More on that note later; it happened to be tucked in on the same page.)

Censors tell me the book was in Italy, probably somewhere in the North, in the 17th century.

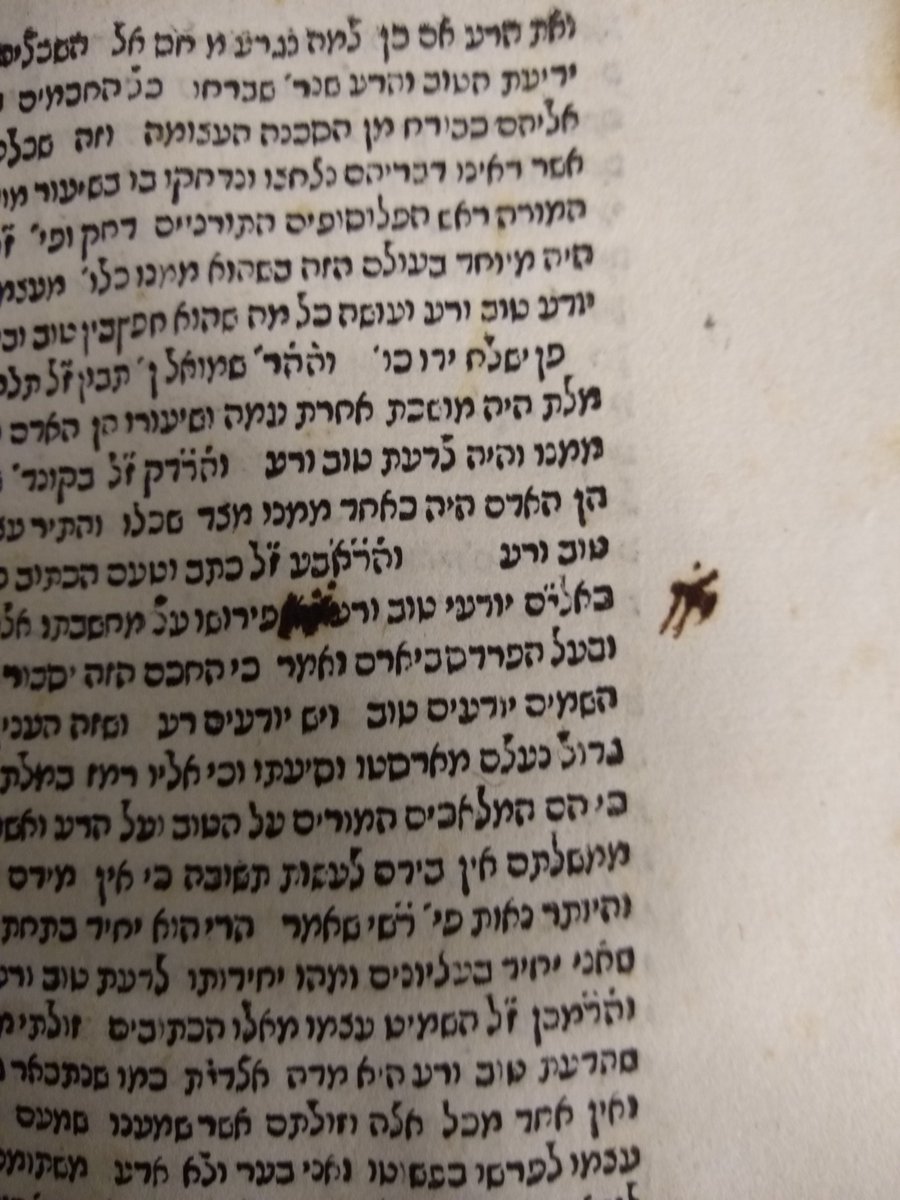

Not a lot of annotations, but the free that are there tell us that our Sephardic friend went through the book very carefully.

As you can see throughout, the book got very wet at some point. I blame the guy with the cup on the opening flyleaf.

As you can see throughout, the book got very wet at some point. I blame the guy with the cup on the opening flyleaf.

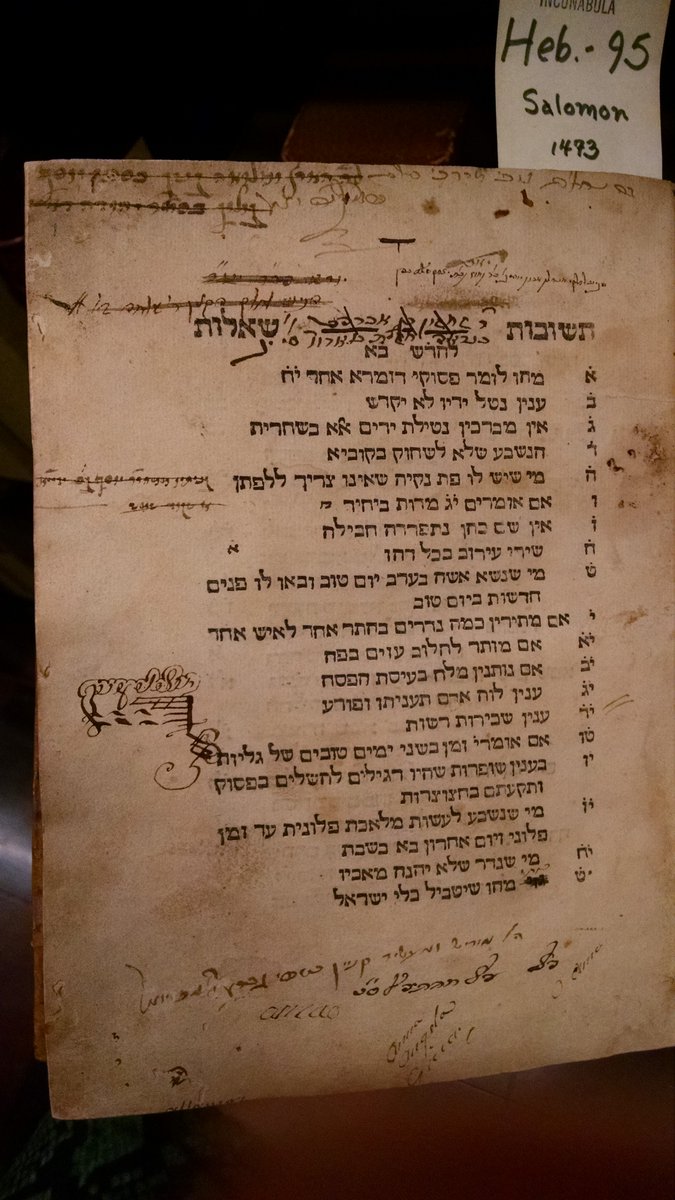

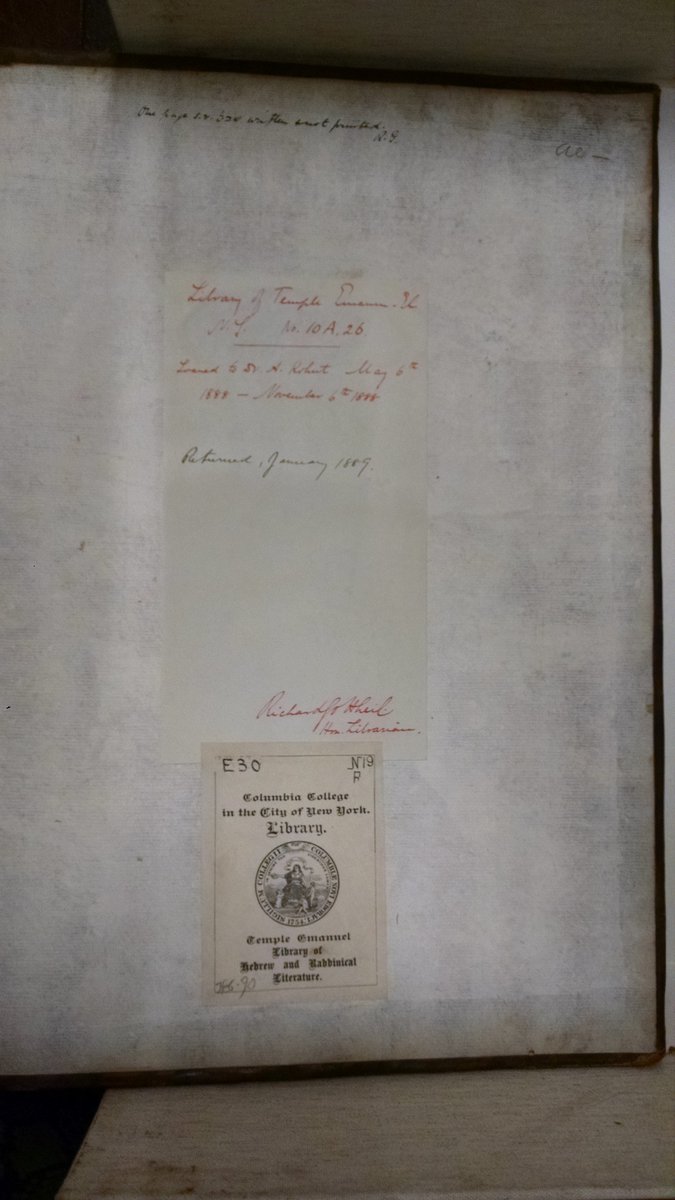

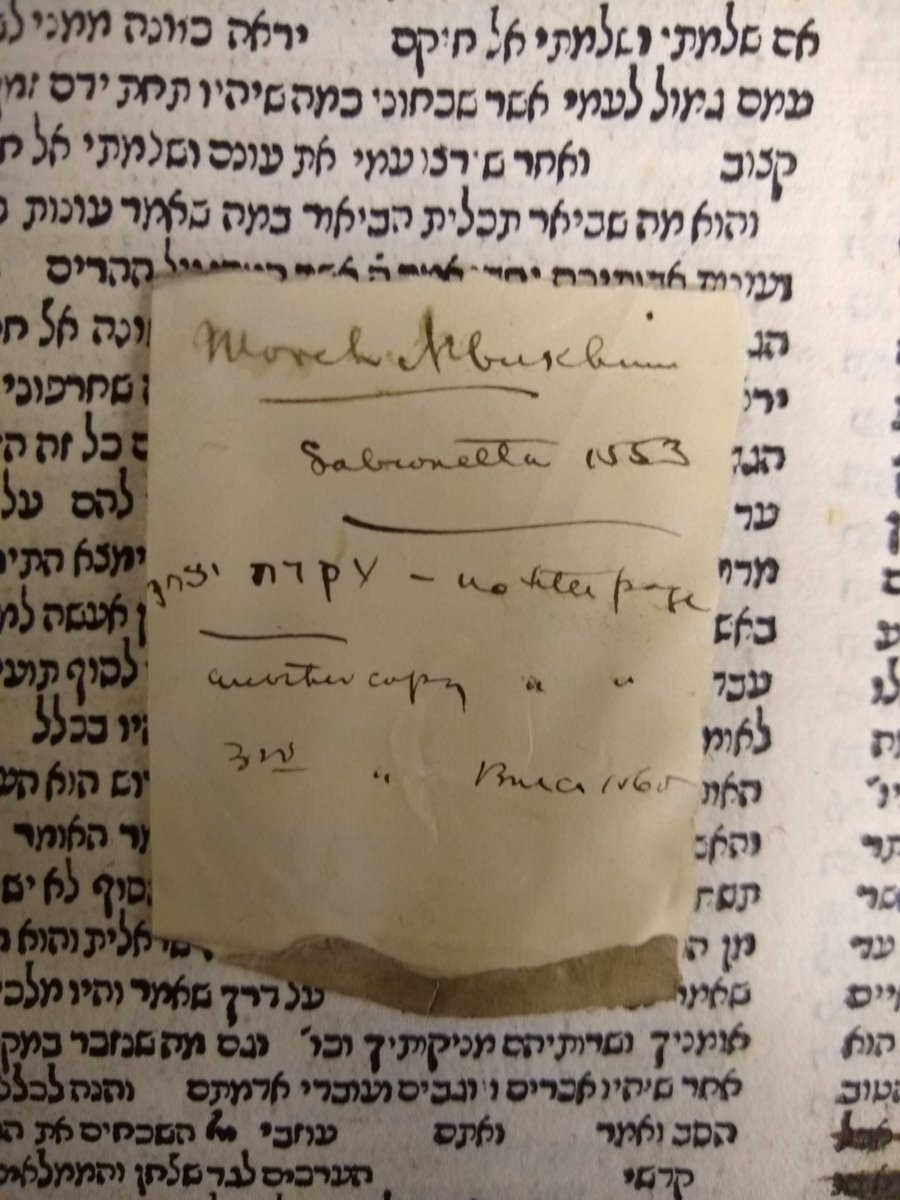

A few last stops that we can identify. The bookplate and accession number tell me that it was given to Columbia by Temple Emanuel in 1892, part of a collection that TE acquired from the Amsterdam bookseller Frederik Müller in 1872. Müller's catalog of the coll came out in 1868.

Who wrote the note? Maybe M. Roest, who cataloged the collection for Müller (the paper is older than it looks, and includes info about other books as well). Who wrote the title on the spine? Maybe Giuseppe Almanzi (d. 1860) who owned part of the collection and wrote on spines.

There are more questions than answers here, but the key here is that all books tell stories. You just have to know how to look! /End

My thanks to Fabrizio Quaglia, who corrected me and read “Visto per me Gio. dominico carretto 1618” for the second one. (Hippolite was in my imagination here..although he was a real censor.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh