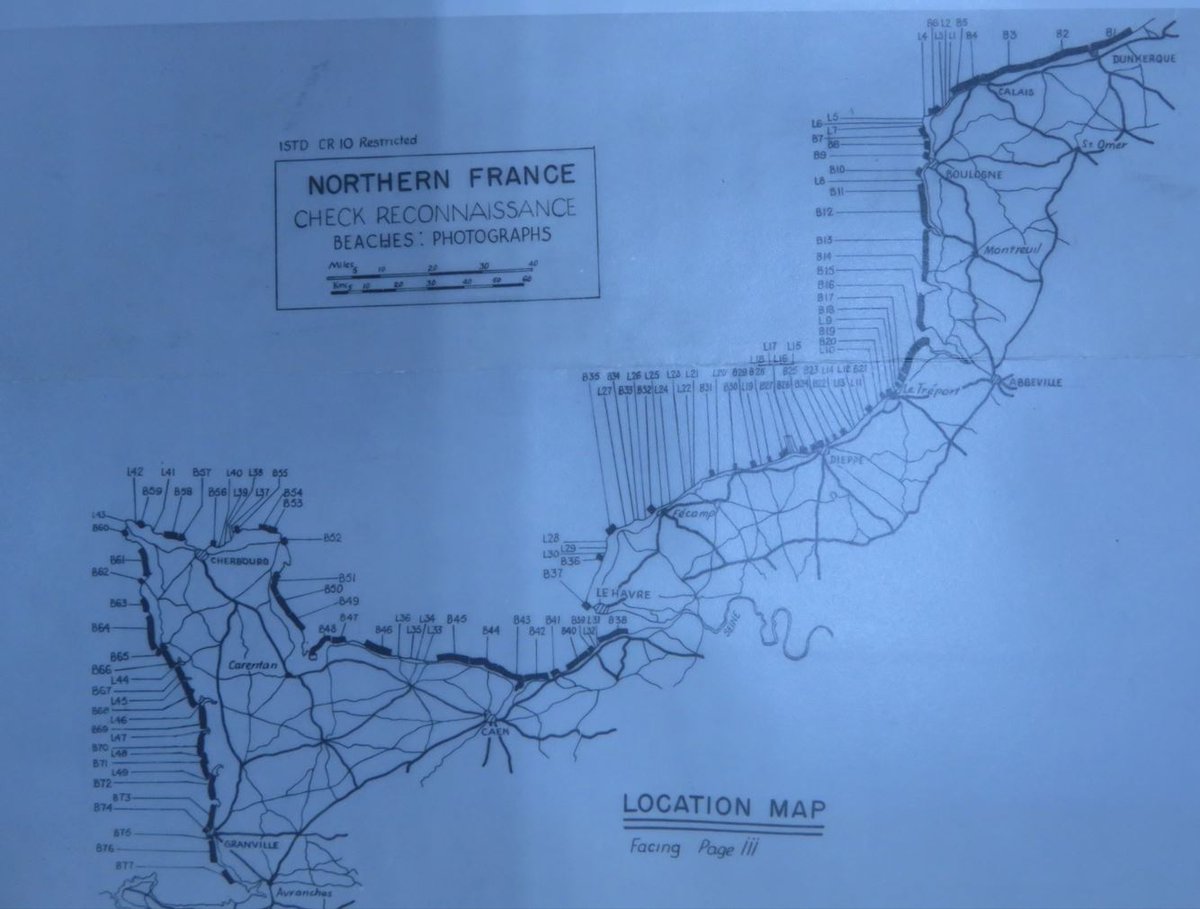

One of the questions on the @Wehaveways livestream 2 weeks ago was about the Landing Vehicle Tracked (LVT), or Buffalo, and why they weren’t used at Normandy. So I thought it would be handy to explain one major reason they couldn’t be deployed.

In a nutshell, we simply didn’t have the amphibious lift capacity to get large numbers of LVTs across the Channel. They needed to be carried by larger landing craft & ships, but the only ones suitable were already allocated for other vehicles – tanks and trucks. 📷IWM B5258

The Royal Navy (for it was they that led Neptune) had evolved its amphibious forces along the lines of separate landing ships/craft for infantry and for vehicles. The LVT, being a vehicle for carrying infantry, didn’t fit very well into that model.

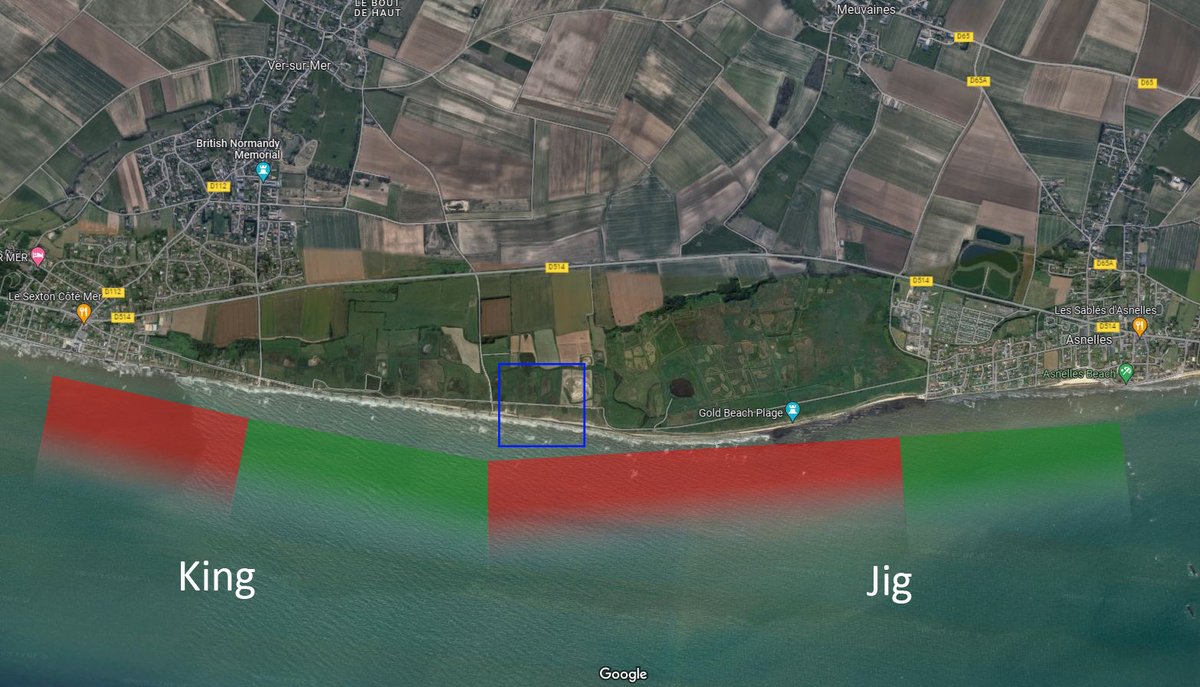

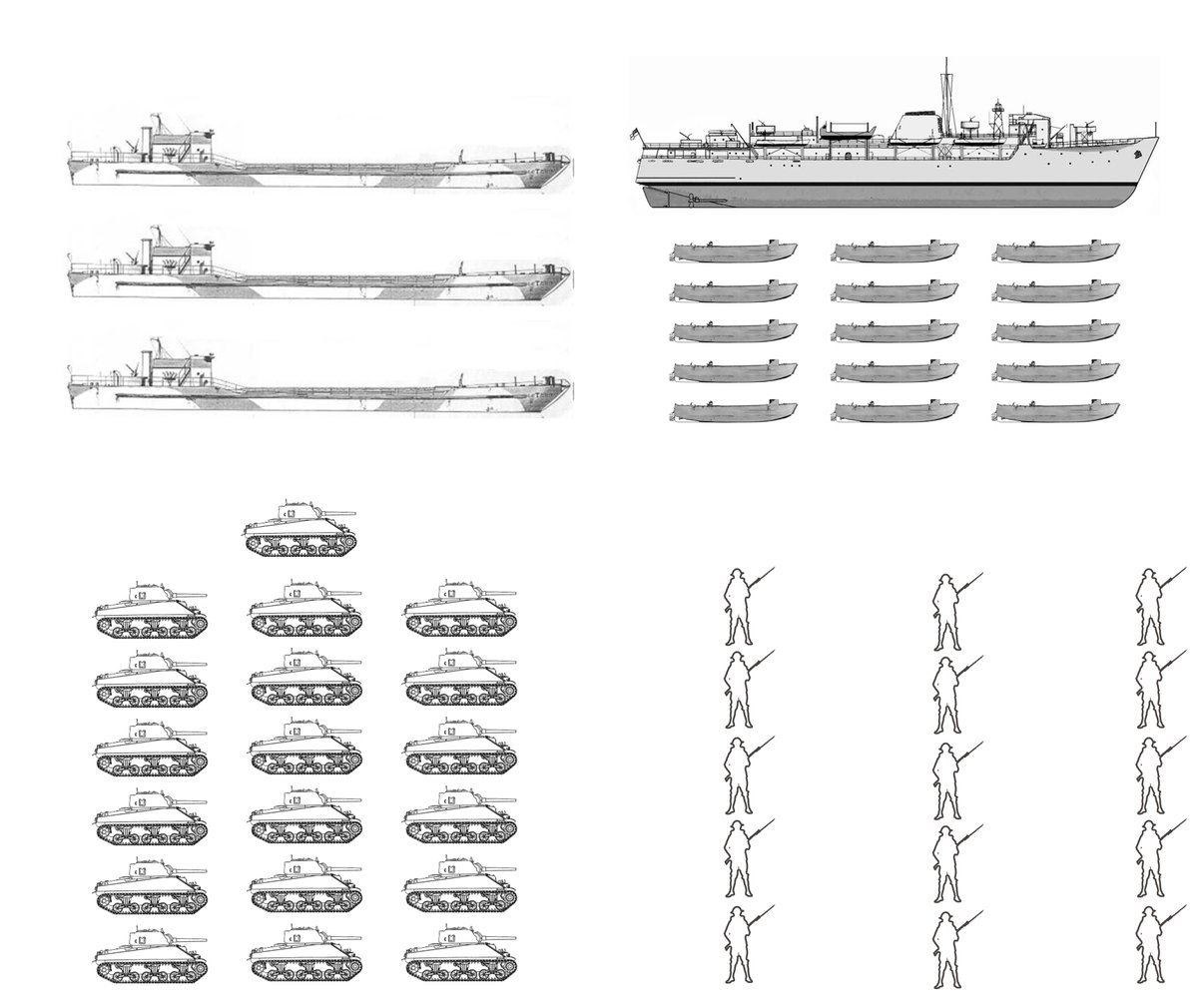

To massively scale down Neptune, let’s just say you want to land a battalion of infantry (no vehicles) and a squadron of tanks. This is massively simplified, but it hopefully gives you an idea of the problem.

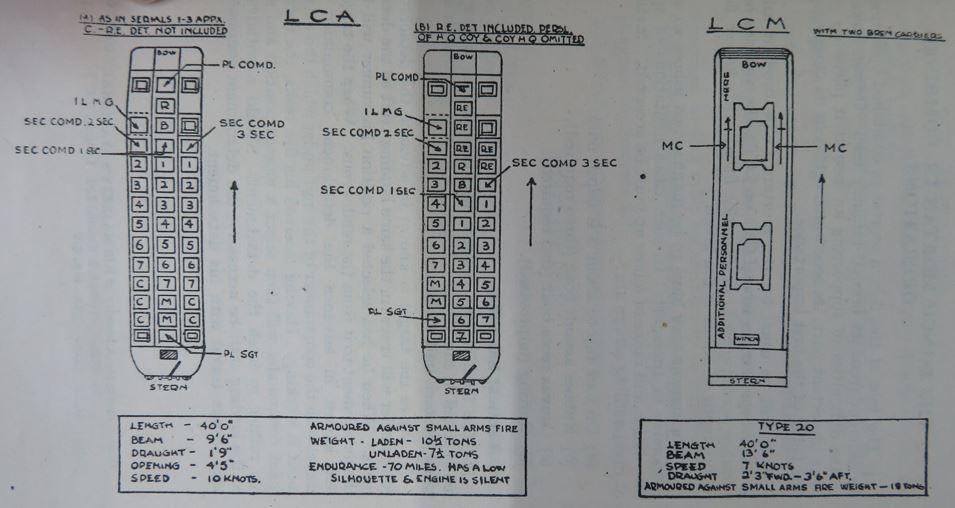

The infantry battalion has 12 rifle platoons plus a few supports (heavy weapons etc…), so for the sake of argument let’s say 15 platoons. A Landing Craft Assault can carry one platoon, so you need 15 LCAs.

The LCA is a ship-to-shore landing craft – it cannot cross the Channel unaided. So they’re carried across in the davits of a larger Landing Ship Infantry. Indeed, many LSI were designed to carry a battalion and a suitable number of LCA to get them ashore.

The armoured squadron is typically 19 tanks, although it might also have some elements of HQ and support attached. But either way, you could easily fit this into 3 Landing Craft Tank Mk IV (roughly 8 per LCT depending on the tank).

The LCT is a shore-to-shore vessel – it can cross the Channel under its own power and doesn’t need a larger carrier. So your amphibious force consists of 3 LCT and 1 LSI carrying 15 LCA, transporting 15 platoons and 19 tanks.

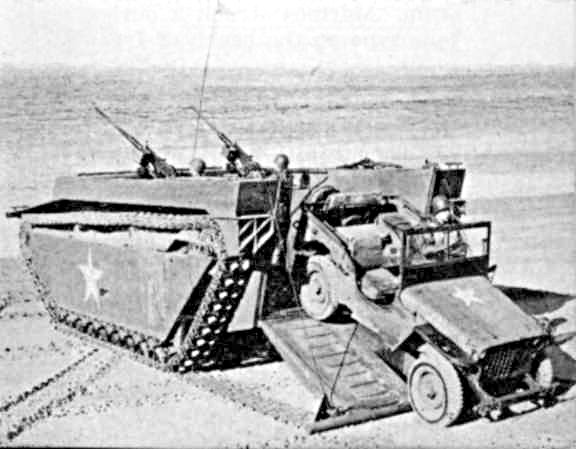

Now, let’s say you want to use LVTs. An LVT can carry 24 men – less than a platoon – but for simplicity’s sake, let’s just round it up to a platoon. So you replace your 15 LCA with 15 LVT.

But, LVTs aren’t capable of crossing the Channel by themselves – they have to be carried. They are too big and heavy to be carried by the LSI though – instead you have to put the LVTs into the LCTs. 📷IWM A 26266

You can fit a maximum of 6 LVT onto the deck of an LCT Mk IV, so you need 3 of them carry your LVTs and your infantry component. The outcome of this is that you’ve made your LSI and 15 LCA redundant, and you’ve displaced all your armour to accommodate your infantry on the 3 LCT.

The Royal Navy had evolved over the past few years to use infantry vessels & vehicle vessels. The LVT didn’t fit into that arrangement & there simply weren’t enough vehicle vessels to carry both the armour & infantry components of an invasion of the scale of D-Day. 📷IWM A 23671

Of course, this also went beyond the logistics of transport – Combined Operations had, for years, been developing the LCA as the primary infantry amphibious assault vessel for years. Loads, training and tactics were all built around it.

Additionally, once an LVT gets onto the beach, what then? The LCAs turned around to pick up more men. If the LVTs would be needed to do the same, they can’t hang around to provide support for the infantry. So one benefit of the LVT is nullified.

What about turreted LVT-As to replace the DDs? At least the transport isn't a problem here, but the LVT only made its combat debut 7 months before D-Day. Training with DDs commenced 14 months before D-Day!

And even if you did use LVT-A's, once ashore, they're simply not as good as tanks. They're useful in inundated terrain, but there wasn't much in Normandy. Armour was needed in Normandy, not amphibious vehicles. So another benefit of the LVT is nullified. 📷NAM. 1985-10-134-15

The LVT worked in the Pacific, where there were more suitable carriers, tanks were not needed in as great numbers, landings were made on smaller fronts and the LVT's ability to cross reefs, inundations and and chaungs was more useful.

But D-Day had a significantly larger landing area & insufficient suitable carriers. Simply put, the LVT entered the war too late to be used as an assault vehicle on D-Day in the numbers required. Amphibious operations of Neptune’s scale were wholly built around the landing craft.

There will be many discussions about how well LVTs might have performed on the beaches, but they're essentially irrelevant if you can’t actually get them there in the first place.

Finit!

Finit!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh