🚨 New from @IndependentSAGE

Our ‘Following the Science’ Timeline charts the main behavioural science recommendations from SAGE & Indie SAGE about the measures needed to minimize the spread of COVID-19 alongside what the Westminster Government implemented and when.

🧵+🔗⬇️

Our ‘Following the Science’ Timeline charts the main behavioural science recommendations from SAGE & Indie SAGE about the measures needed to minimize the spread of COVID-19 alongside what the Westminster Government implemented and when.

🧵+🔗⬇️

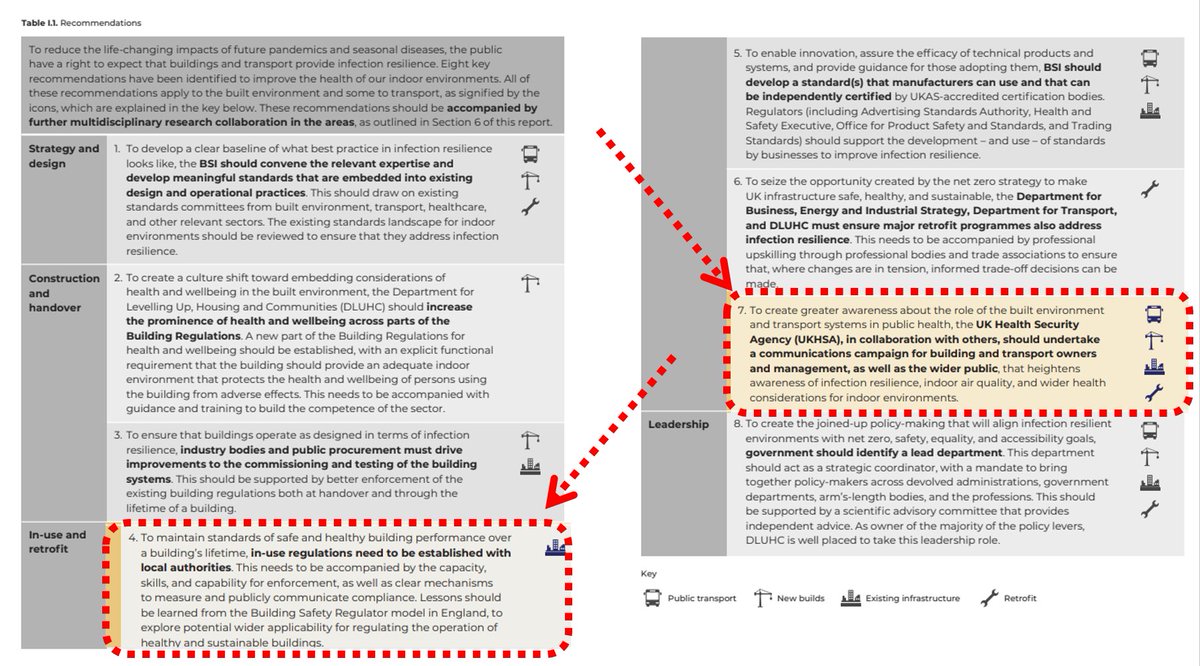

2. The timeline covers four main areas: hand and respiratory hygiene, face coverings, physical distancing, and self-isolation...

3. ...it also covers selected events, news, and dates as an aide memoire, and some dates about emerging science (e.g., the airborne nature of Covid) where it had implications for behaviours like wearing face coverings or opening windows.

4. The timeline does not systematically include travel regulations or the testing and vaccination programmes. It also focuses on the Westminster government’s actions, since Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and England diverged in approach following ‘Stay Alert’ in May 2020.

5. The information underpinning the Timeline draws on SAGE papers and minutes; Independent SAGE reports, statements, and media; media reports of SAGE papers; media articles about changes to guidance and regulation, and @instituteforgov's timeline of lockdowns (links in report).

6. The 'Following the Science' Timeline also builds on and extends our own earlier timelines about UK government messaging and Indie SAGE reports.

🔗independentsage.org

🔗independentsage.org

7. The timeline shows lots of divergence, from delaying the second ‘circuit-breaker lockdown’ in autumn 2020 to setting out a ‘road map’ based on fixed dates while talking about ‘data not dates’. Here are some of the main behavioural examples:

8. While scientists recommended support, and advised against fines and punitive measures to try to get people to follow regulations - for both adherence and inequalities reasons, the UK government nevertheless introduced fines.

9. Back in April 2020, SAGE advised that, in future, good practice is not to lift measures 'all in one go'. But the 'big bang' headlines came on 19th July 2021 for so-called 'Freedom Day' (although the government is still making recommendations and publishing guidance...).

10. IndieSAGE advised against reducing 2m distancing to 1m/plus. After 'Stay Alert', the messaging became vague (e.g., "2m where possible"; "Stay at least 2m apart; "1m with a face covering or other precautions"). But 2m - easy to remember, approximate, & signpost - stuck anyway.

11. ...and plenty of people in England still want physical distancing measures in place - @YouGov polling from a couple of weeks ago:

12. The government was also slow to implement face-covering requirements. As early as Feb 2020, Nervtag minutes included recommendations for symptomatic people to wear them, though there was much debate for some time about their effectiveness.

13. In March 2020, the Chinese CDC director George Fu Gao said: "The big mistake in the U.S. and Europe, in my opinion, is that people aren't wearing masks. The US CDC recommended them from April 2020.

npr.org/sections/goats…

npr.org/sections/goats…

14. The UK gov lifted mask regulations on 19th July in England (but still recommends them!); YouGov polling shows people still want masks on public transport; people think hand/surface washing are more effective than masks and ventilation...

https://twitter.com/DrWilkinsonSci/status/1428475536112857093

15. Finally, scientists were consistent about the need for good #communication, but UK gov messaging was a problem from ‘Stay Alert’ onwards, marked by a lack of clarity, consistency, timeliness, trustworthiness, and 'enact-ability'.

16. @IndependentSage published a report, with recommendations, on messaging and communication (with another timeline) in November 2020.

https://twitter.com/LizStokoe/status/1328403950693965827

17. In sum:

The Timeline charts emerging and continuing UK government confusion - from this week's self-isolation changes to the gaps between 'Freedom Day' ('no legal requirements') & nevertheless publishing guidance and recommendations.

🧵end

🔗⬇️📰 independentsage.org/following-the-…

The Timeline charts emerging and continuing UK government confusion - from this week's self-isolation changes to the gaps between 'Freedom Day' ('no legal requirements') & nevertheless publishing guidance and recommendations.

🧵end

🔗⬇️📰 independentsage.org/following-the-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh