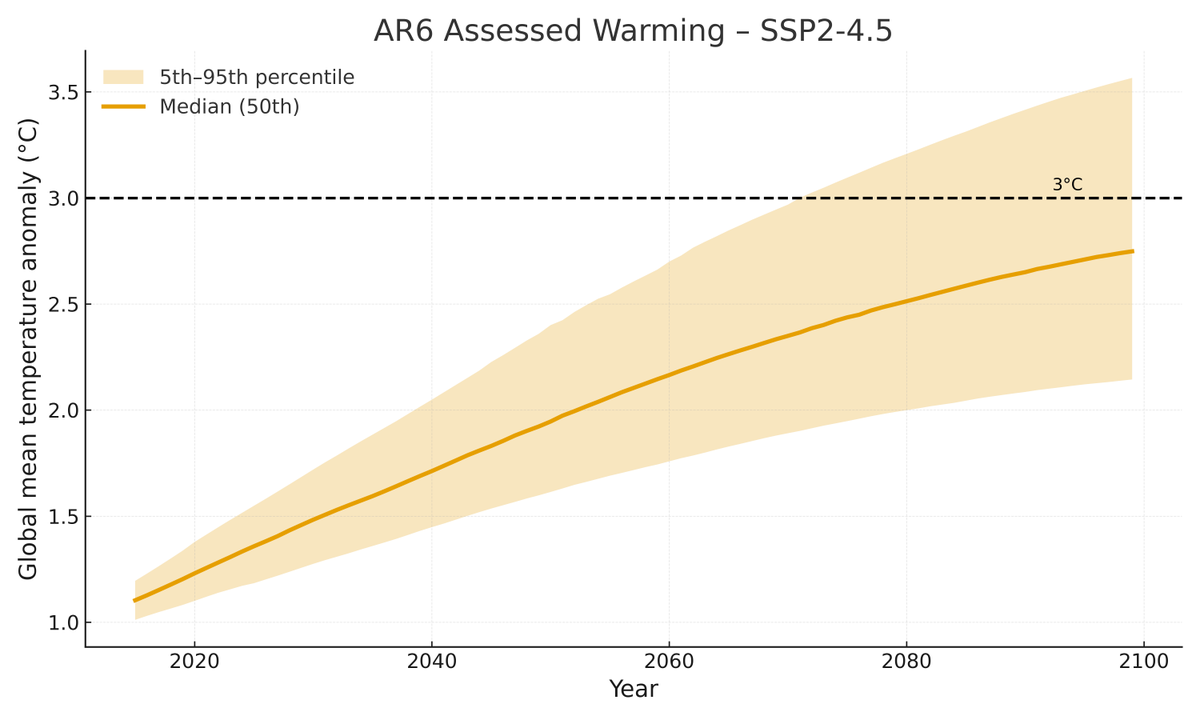

One under-appreciated finding in the IPCC AR6 is a lot more certainty around future warming.

Previously IPCC only gave "likely" warming ranges (e.g. a 2 in 3 chance of falling in the range). New report gives "very likely" 9 in 10 ranges. Here is a rough like-to-like comparison:

Previously IPCC only gave "likely" warming ranges (e.g. a 2 in 3 chance of falling in the range). New report gives "very likely" 9 in 10 ranges. Here is a rough like-to-like comparison:

The IPCC AR5 future warming projections were nominally based on the 90th percentile of CMIP5 models, but the assessed range of climate sensitivity was much wider than the range in CMIP5 models, so these were treated "likely" (66th percentile) ranges.

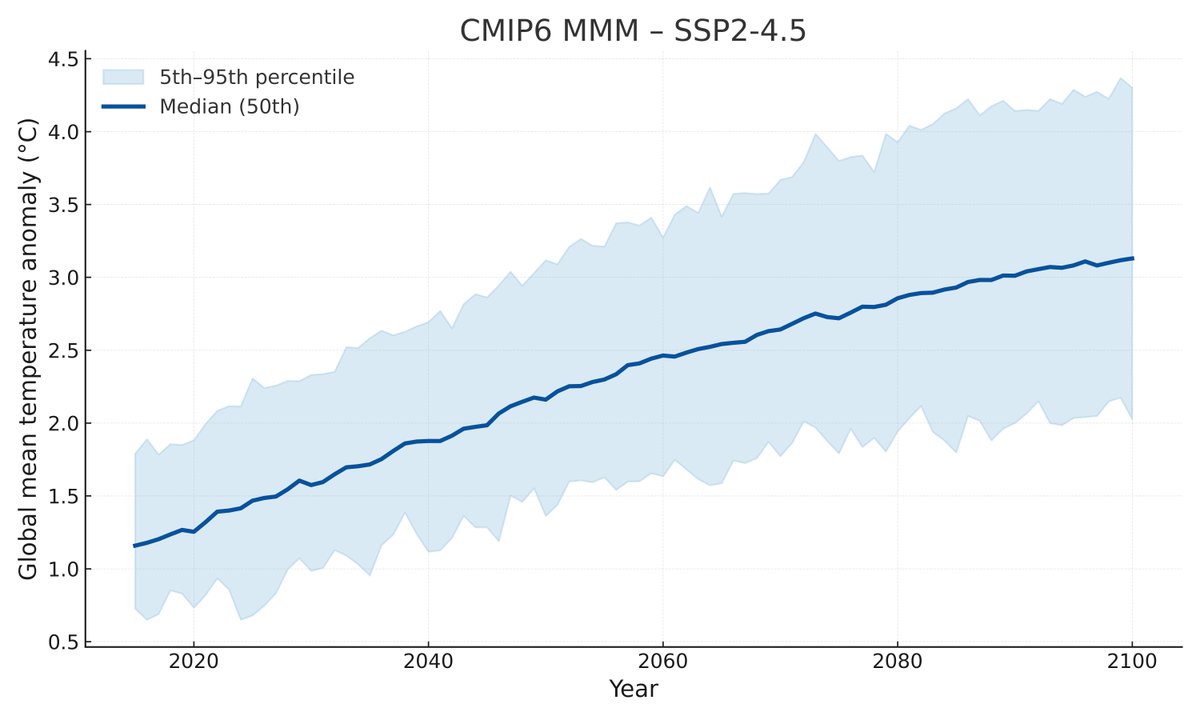

The AR6, on the other hand, bases its warming projections on a combination of observationally-constrained CMIP6 models and a simple energy balance model using the new transient climate response (TCR) and equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) values in the report.

Per the AR6 WG1 Chapter 4: "Because different approaches... produce consistent results, there is high confidence in this assessment. These ranges... generally correspond to AR5 ranges... but likelihood is increased to very likely ranges, in contrast to the likely ranges in AR5."

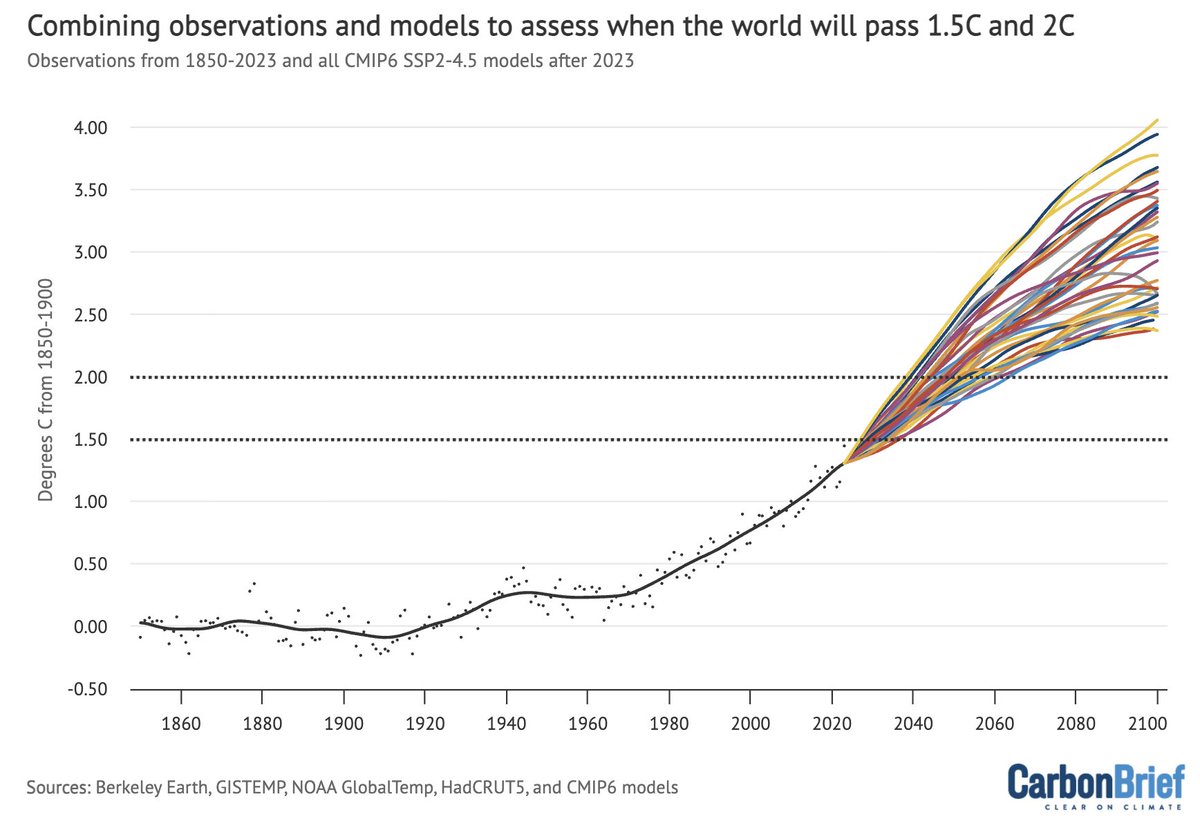

Here is what the published RCP AR5 warming projections look like compared to the SSP AR6 ones; note that the AR5 ranges are "likely" 66th percentile ranges and the AR6 ones are "very likely" 90th percentile ranges.

There were no "very likely" ranges published in the AR5 to allow a direct comparison of scenarios. However, if we scale the AR5 projections by the difference between "likely" and "very likely" climate sensitivity (ECS) ranges we can get a rough estimate:

As an aside, TCR would probably be better than ECS to use for scaling these, but as far as I can tell the AR5 did not provide a "very likely" TCR range.

This increased confidence in future warming projections was in part a result of a narrowing of the range of climate sensitivity in the AR6 through a combination of multiple lines of evidence, following the Sherwood et al review: agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.10…

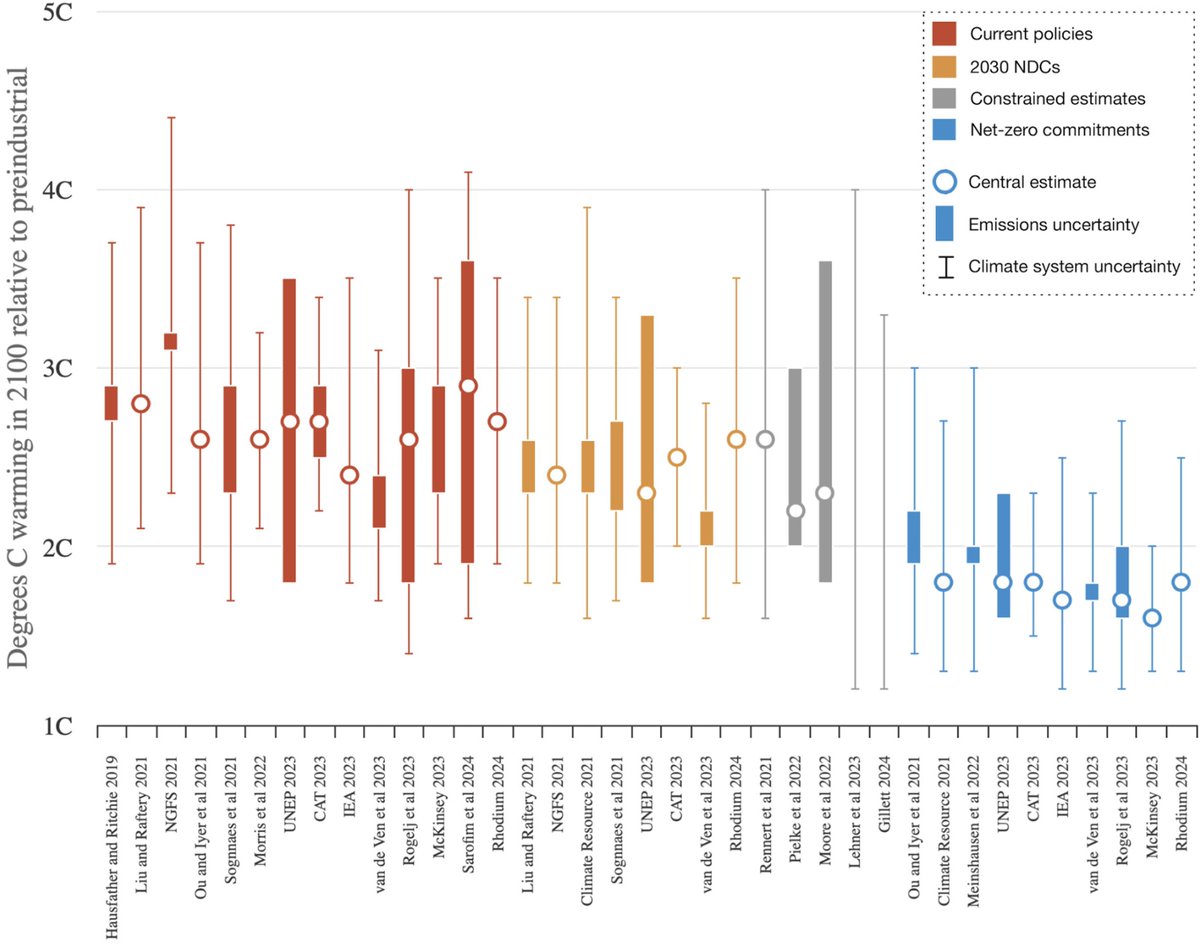

So why is this important? Narrowing the range of future warming represents both good and bad news: good news that some of the very high end warming outcomes now seems less likely, but bad that we much less likely to get lucky and end up with less warming than we expected.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh