Today 7 September is the anniversary of one of the greatest crusader victories, the Battle of Arsuf in 1191 during the Third Crusade! The legendary King Richard the Lionheart led the crusaders to victory against a twice larger force of Saracens led by the famed commander Saladin!

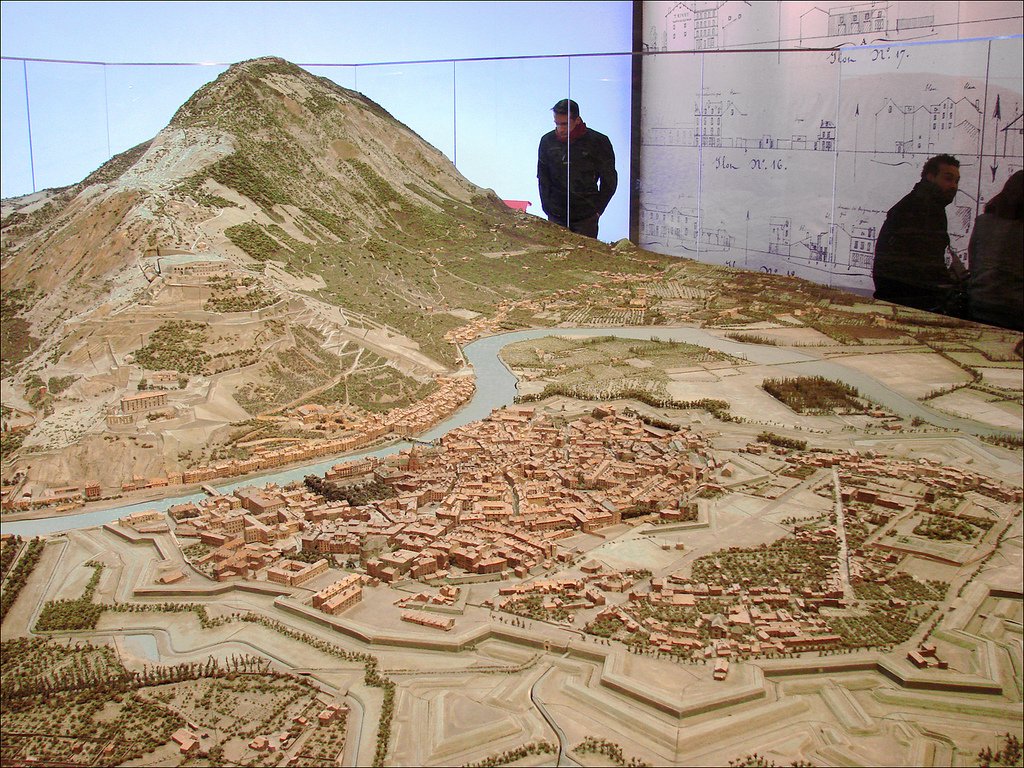

The battle of Arsuf happened as the crusaders marched by the sea from the newly conquered Acre to Jaffa, and were routinely harassed by Saladin's cavalry and archers. Richard's plan was to (re)conquer the coast for the crusader state of Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Richard demanded strict discipline from his army and ordered them to not respond to provocations. He put crossbowmen in the outer lines to fire back on the Saracens and rotated infantry units that were under pressure from constant attacks so he could keep his army fresh.

Saladin's skirmish attacks were not as effective as he thought they would be, and the crossbows of the crusaders proved to be very powerful and feared. They did much more damaged than arrows from Saracen archers. Saladin decided to fully engage Richard the Lionheart's army.

This engagement would happen on 7 September near Arsuf. Saladin gathered a force that outnumbered the crusaders at least two-to-one (three-to-one in crusader sources, but likely exaggerated), with around 26000 men, majority of whom were cavalry. He faced around 12000 crusaders.

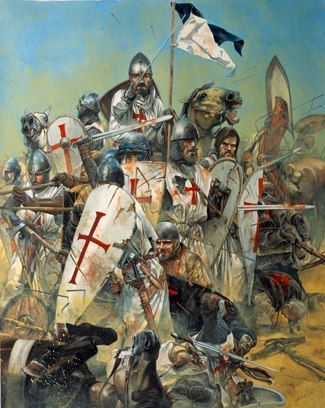

The crusaders were mostly infantry but had enough heavy cavalry of Knights Hospitaller, Templars and European knights to be able to make a powerful charge. Richard, however, wanted to wait until Saladin's army fully engaged with him until making any sort of offensive moves.

Richard arranged his army into twelve squadrons, which were divided proportionally into five battalions. Behind their back they were protected by the sea. Their illustrious banners were proudly displayed as they faced the strong enemy coming at them with arrows and retreating.

Crusader chronicle Itinerarium Regis Ricardi describes the various races fighting for Saladin, mentioning Bedouins and Turks and many others: "The forces of Paganism had gathered together, from Damascus and Persia, from the Mediterranean Sea to the East."

The Chronicle continues: "There was not a famous or powerful man or a people of valour or a bold race proven in the practice of war or anyone of action remaining even in the extreme corners of the earth whom Saladin had not summoned to aid him in crushing the Christian people."

The pressure from the Saracen enemy was fierce, but crusaders were able to inflict a lot of damage with crossbows. "How essential those valiant crossbowmen and archers were that day! [They] drove back the relentless Turks as best as they could with a continuous volley of shots."

However the Saracens were also able to inflict a lot of damage and their pressure continued. This frustrated many knights who wanted to attack, but were forbidden to do so by Richards ultra-defensive approach to the battle. Richard wanted to tire the enemy and force him to engage

"The sun’s light was dimmed by the great number of missiles, as it does in winter in thick hail or snow. Horses were pierced by the points of darts and arrows" The weather was also not kind to the armored crusaders, as it was extremely hot on that day.

Furthermore a lot of crusader horses died from the arrows and the knights had to dismount and joined infantry. This made the knights even more anxious to counter-attack, especially Hospitallers who were under the most pressure and reported that they couldn't hold much longer.

The Hospitallers finally decided to charge on their own, with their Grand Master Garnier de Nablus and one valiant knight Baldwin de Carron leading the charge with battle cries of st. George! The rest of the knights follow and Richard himself rode to help and joined the battle.

"No one escaped when [King Richard's] sword made contact with them; wherever he went his brandished sword cleared a wide path on all sides. Continuing his advance with untiring sword strokes, he cut down that unspeakable race as if he were reaping the harvest with a sickle."

The charge inflicted a lot of damage as the Saracens were close to crusaders and many of them dismounted so that they could fire more accurately. However Richard wisely halted the charge after about a mile as he didn't want to disperse over too large of an area.

This allowed the Saracens to regroup and Richard needed to rally his knights for three more charges. One of the knights William des Barres particularly distinguished himself in these charges when he burst out of line and charged the enemy headlong with his company.

"The king no less, mounted on a dun Cypriot horse which was without equal, sprang forward towards the mountains with his elite troops and scattered any Turks he met. They fell back from him on all sides, with helmets ringing and sparks flying from the striking of iron on iron."

"God and the Holy Sepulchre, help us!" shouted Richard the Lionheart before completely breaking the Mohammedan army in the finale charge and putting them to rout, killing around 7000 of them and defeating the mighty Saladin! It was a crucial victory for the crusaders!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh