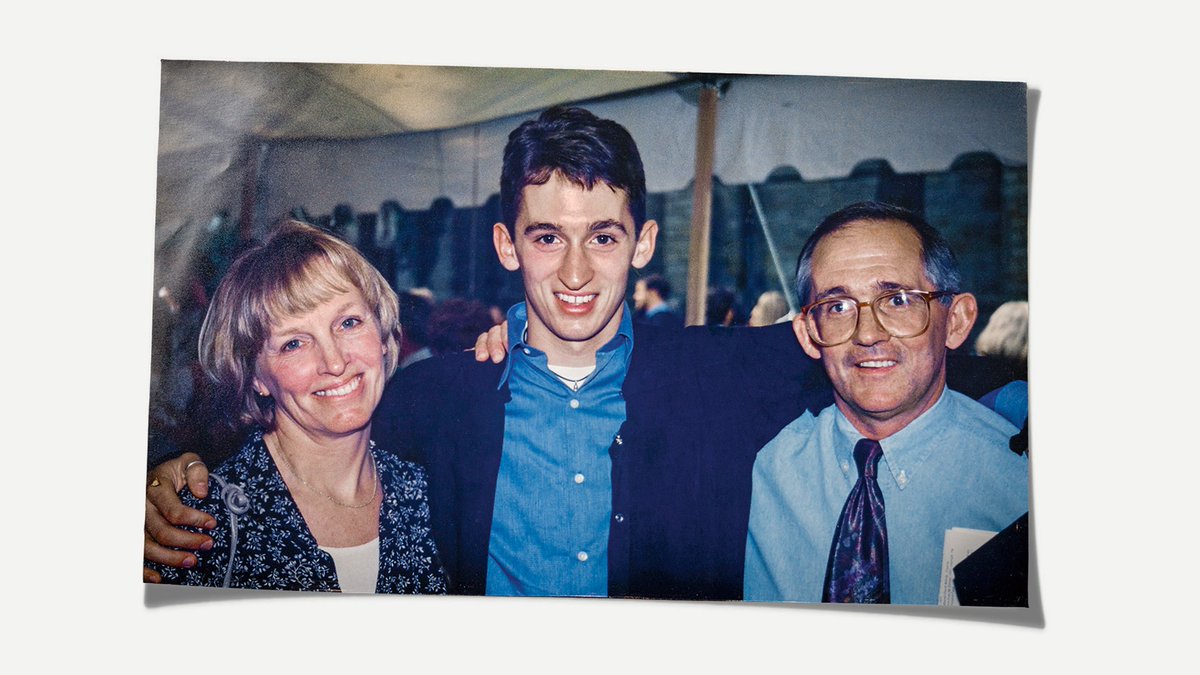

1/10 Bobby McIlvaine died when the Twin Towers fell—before his life truly began. His father dove into his grief. His mother pushed hers away. Twenty years later, it’s changed them both.

@JenSeniorNY on a family’s search for meaning after 9/11:

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

@JenSeniorNY on a family’s search for meaning after 9/11:

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

2/10 For Helen McIlvaine, nothing in this world has rivaled the experience of raising her two boys. “A few years down the road, I looked like I’d healed. And it wasn’t true.” At age 60, Helen took up running, not only because it felt good, but also because it allowed her to cry.

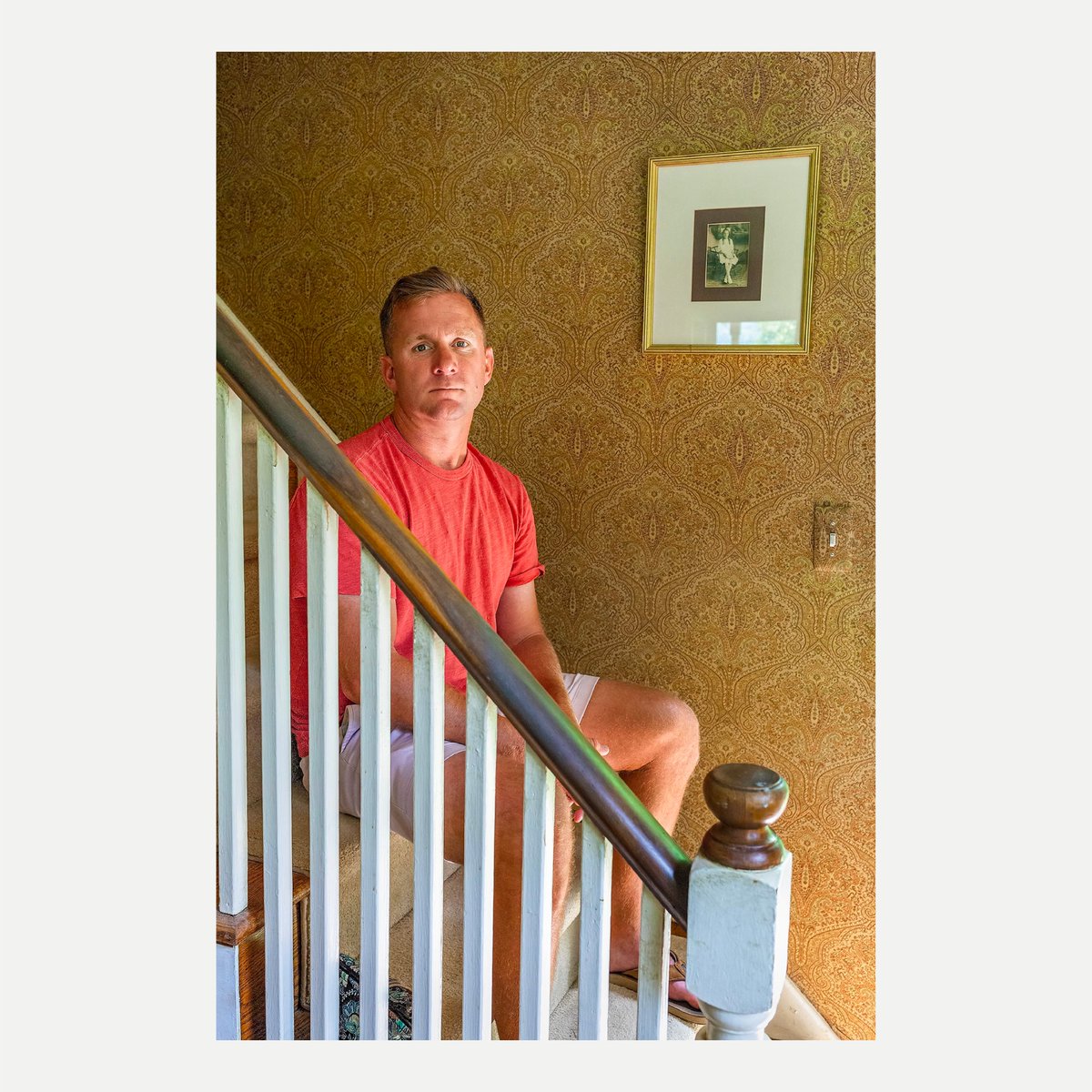

3/10 Bob McIlvaine Sr. knows little about his son’s final moments but is committed to exposing what he believes to be the truth about the 9/11 attacks, which is that they were an inside job. “Everything I’ve done in my life is based upon those seconds,” he says.

4/10 Bob Sr. didn’t wake up on September 12, 2001, believing such things. They have taken shape over the span of years as a way for him to keep his son’s memory near to him.

5/10 Bob Sr.’s crusade may look to the outside world like madness. Helen sees it as an act of love. “He’s being a father in the best way he knows how.”

6/10 Helen and Bob Sr. do not agree on who is responsible for their son’s death, but are bonded by their love and grief. For Helen, Bob Sr. is “the only other person in the world,” Senior writes, “who understands what it feels like to have raised Bobby McIlvaine and lost him.”

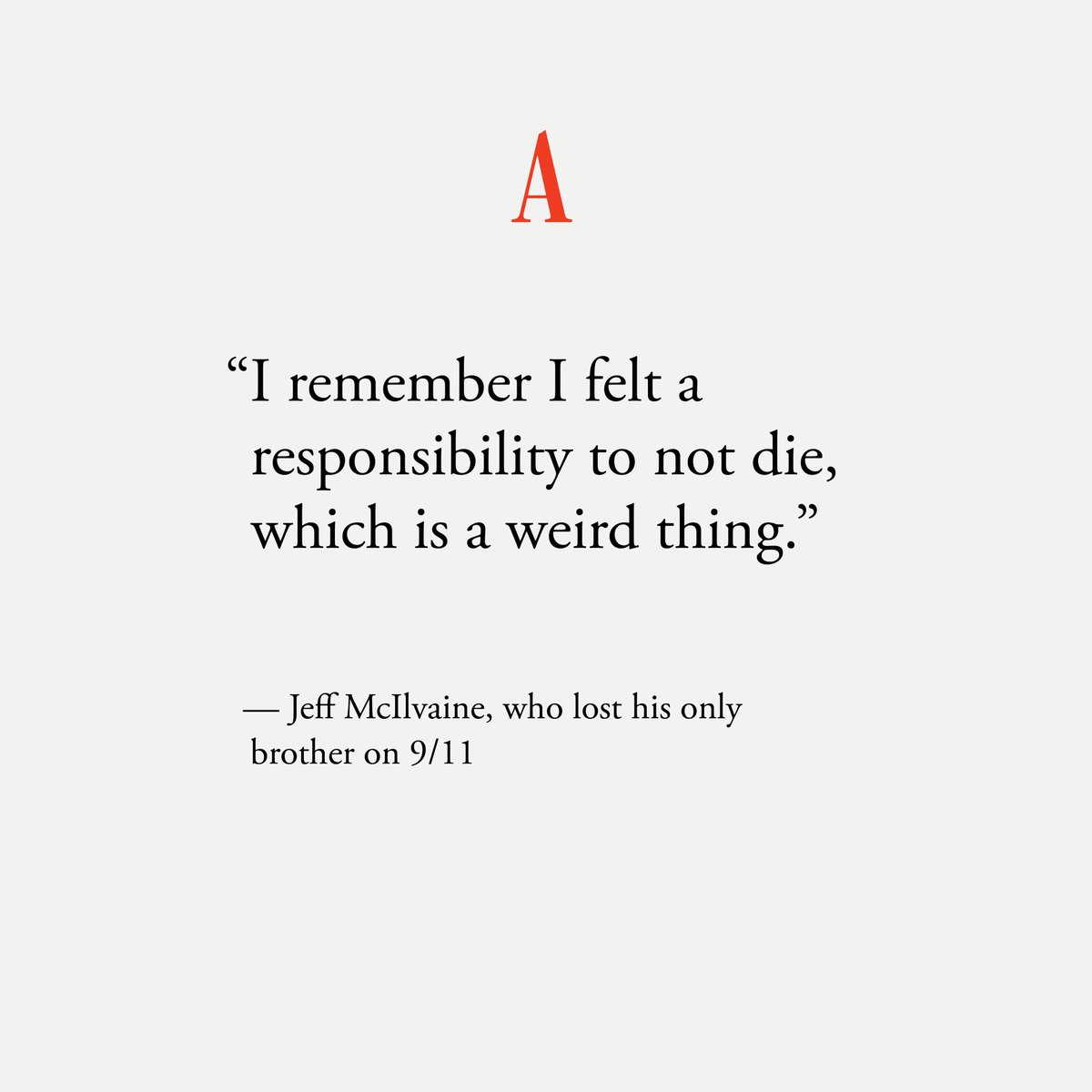

7/10 Bobby’s lone sibling, Jeff, a father of four, never wants any of his children to feel the pain he felt when his brother died. “When you go through something like this, you realize that family—it’s the only thing.”

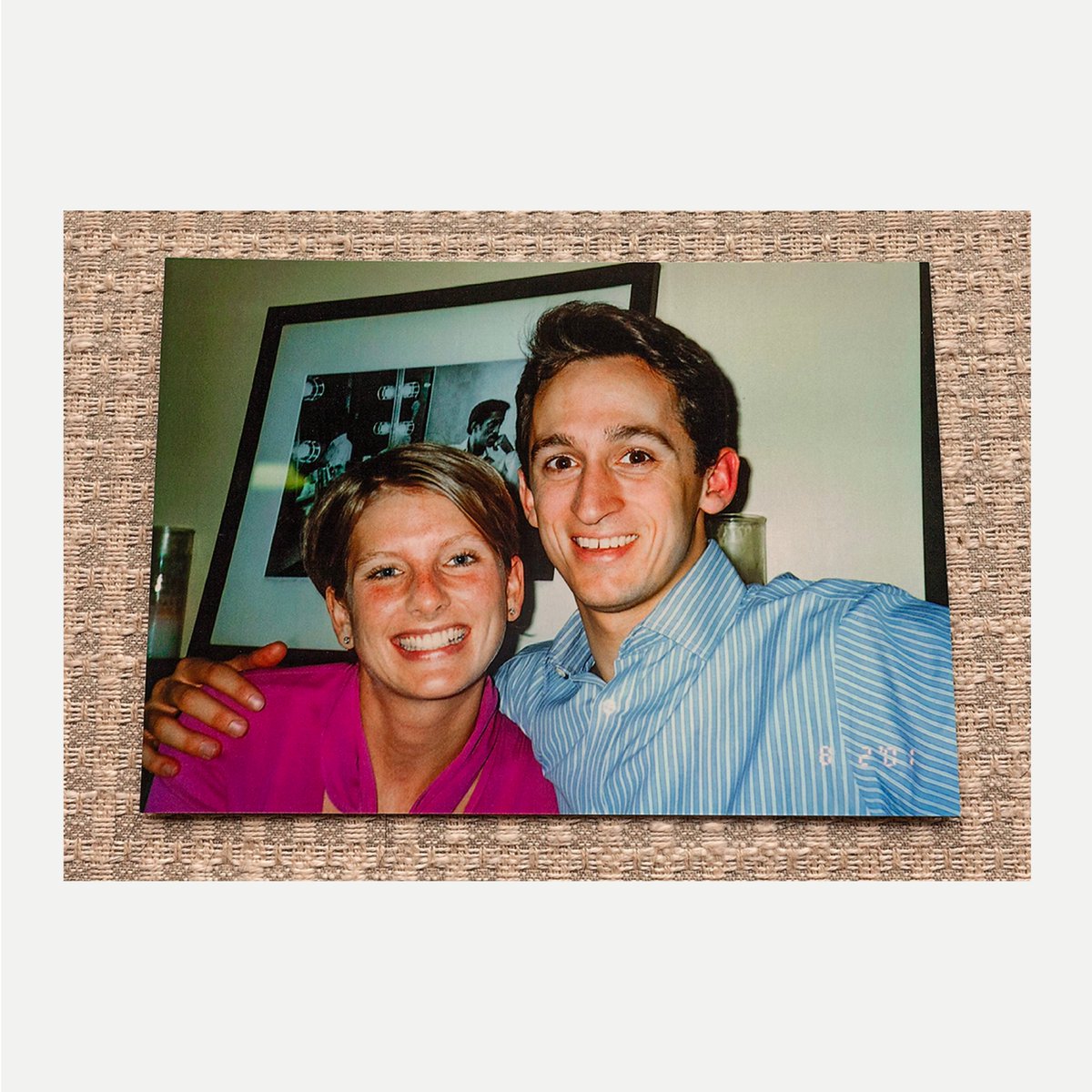

8/10 Bobby’s then-girlfriend, Jen, was already mourning the loss of her mother. After he died, Jen was “double grieving.” She’d now lost the man who, days before his death, had planned to propose.

9/10 Today, Jen has made for herself what is, to all outward appearances, a lovely life. But she had to assemble that life brick by brick, and she works hard to keep the joints from coming apart.

10/10 Read our September cover story by @JenSeniorNY, “What Bobby McIlvaine Left Behind”:

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

theatlantic.com/magazine/archi…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh