You are (probably) wrong about probability.

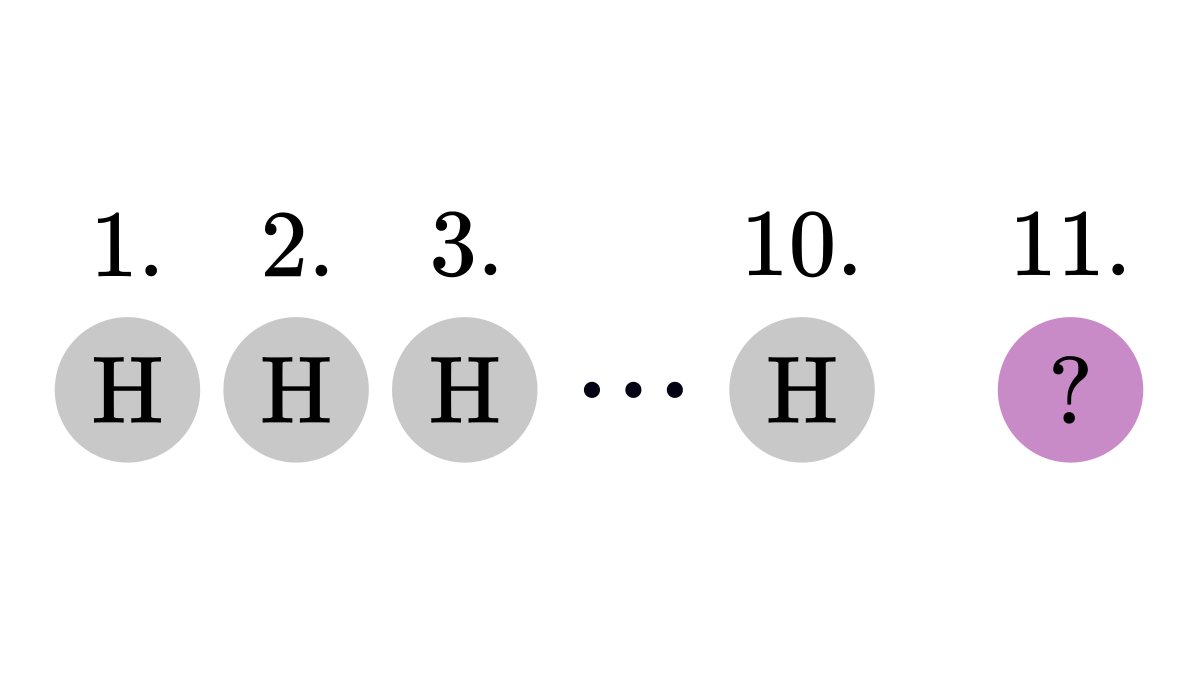

If I toss a fair coin ten times and it all comes up heads, what is the chance that the 11th toss will also be heads? Many think that it'll be highly unlikely. However, this is incorrect.

Here is why!

↓ A thread. ↓

If I toss a fair coin ten times and it all comes up heads, what is the chance that the 11th toss will also be heads? Many think that it'll be highly unlikely. However, this is incorrect.

Here is why!

↓ A thread. ↓

In probability theory and statistics, we often study events in the context of other events.

This is captured by conditional probabilities, answering a simple question: "what is the probability of A if we know that B has occurred?".

This is captured by conditional probabilities, answering a simple question: "what is the probability of A if we know that B has occurred?".

Without any additional information, the probability that eleven coin tosses result in eleven heads in a row is extremely small.

However, notice that it was not our case. The original question was to find the probability of the 11th toss, given the result of the previous ten.

However, notice that it was not our case. The original question was to find the probability of the 11th toss, given the result of the previous ten.

In fact, none of the previous results influence the current toss.

I could have tossed the coin thousands of times and it all could have came up heads. None of that matters.

Coin tosses are 𝑖𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑝𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑛𝑡 of each other. So, we have 50% that the 11th toss is heads.

I could have tossed the coin thousands of times and it all could have came up heads. None of that matters.

Coin tosses are 𝑖𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑝𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑛𝑡 of each other. So, we have 50% that the 11th toss is heads.

(If we don't know that heads and tails have equal probability, having 11 heads in a row might raise suspicions.

However, that is a topic for another day.)

However, that is a topic for another day.)

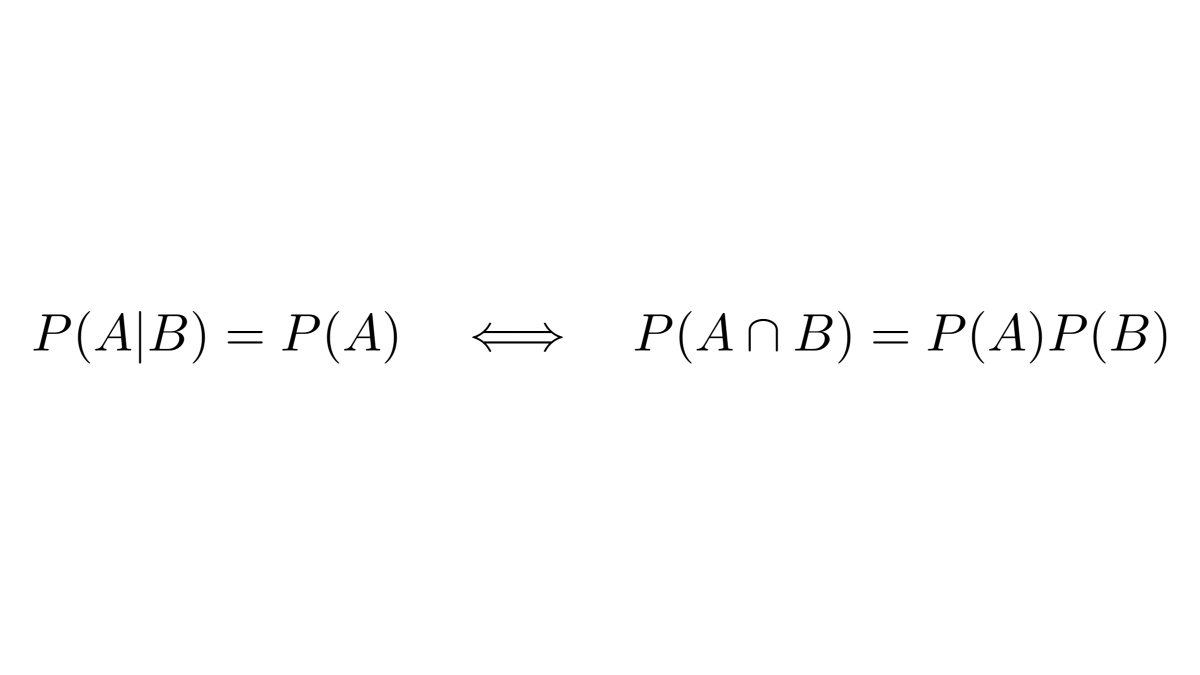

Mathematically speaking, this is formalized by the concept of independence.

The events 𝐴 and 𝐵 are independent if observing 𝐵 doesn't change the probability of 𝐴.

The events 𝐴 and 𝐵 are independent if observing 𝐵 doesn't change the probability of 𝐴.

However, people often perceive that the frequency of past events influences the future.

If I lose 100 hands of Blackjack in a row, it doesn't mean that I ought to be lucky soon. Hence, this phenomenon is called the Gambler's fallacy.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gambler%2…

If I lose 100 hands of Blackjack in a row, it doesn't mean that I ought to be lucky soon. Hence, this phenomenon is called the Gambler's fallacy.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gambler%2…

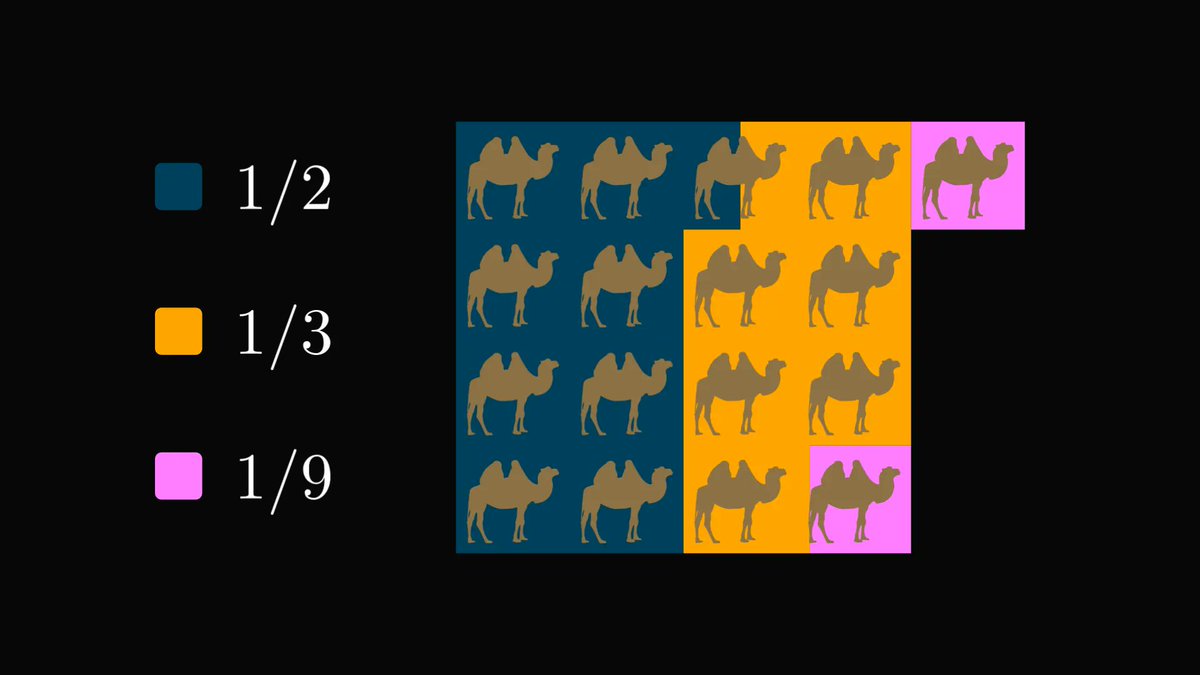

In fact, long runs of the same outcomes will happen if the sample size is large enough.

You can check that for yourself with Python.

Below, I simulated 1000 independent coin tosses and highlighted the parts with at least ten heads in a row.

You can check that for yourself with Python.

Below, I simulated 1000 independent coin tosses and highlighted the parts with at least ten heads in a row.

We can actually use runs of matching outcomes to determine if a sequence is truly random.

This method is called the Wald–Wolfowitz runs test.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wald%E2%8…

This method is called the Wald–Wolfowitz runs test.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wald%E2%8…

I frequently post threads like this, diving deep into concepts in machine learning and mathematics.

If you have enjoyed this, make sure to follow me and stay tuned for more!

The theory behind machine learning is beautiful, and I want to show this to you.

If you have enjoyed this, make sure to follow me and stay tuned for more!

The theory behind machine learning is beautiful, and I want to show this to you.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh