Hard to convey my excitement at seeing an argument by @ojblanchard1 for a networks perspective on three seemingly distinct kinds of fragility.

This is something that I have worked on for a few years now, and I hope that network theory can really help.

1/

This is something that I have worked on for a few years now, and I hope that network theory can really help.

1/

I think it's right that there are commonalities between the fragility of

(i) production when institutions are shocked;

(ii) financial systems when asset values are shocked;

(iii) supply when shipping technology is shocked.

2/

(i) production when institutions are shocked;

(ii) financial systems when asset values are shocked;

(iii) supply when shipping technology is shocked.

2/

One perspective that network theorists have been especially interested in is that there is something qualitative about some collapses: it's not just a matter of some things working worse, but the whole system entering a crisis.

3/

3/

In two papers published in 2014-15, some network theory was brought to bear on the financial crisis. Acemoglu, Ozdaglar, and Tahbaz-Salehi showed that the same structures that are robust to normal shocks are especially bad for the rare large shocks.

citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/downlo…

4/

citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/downlo…

4/

That is the large shocks trigger a crisis.

Simultaneously, Elliott, @JacksonmMatt and I looked at large stochastic financial networks, and found that diversification and integration can both exacerbate the network linkages that make a network susceptible to crises.

5/

Simultaneously, Elliott, @JacksonmMatt and I looked at large stochastic financial networks, and found that diversification and integration can both exacerbate the network linkages that make a network susceptible to crises.

5/

Link mfm.uchicago.edu/wp-content/upl…

Blanchard emphasizes a similarity between domino effects in financial networks and dominoes of failure in real production. Though the economics is different, this analogy seems potentially fruitful!

6/

Blanchard emphasizes a similarity between domino effects in financial networks and dominoes of failure in real production. Though the economics is different, this analogy seems potentially fruitful!

6/

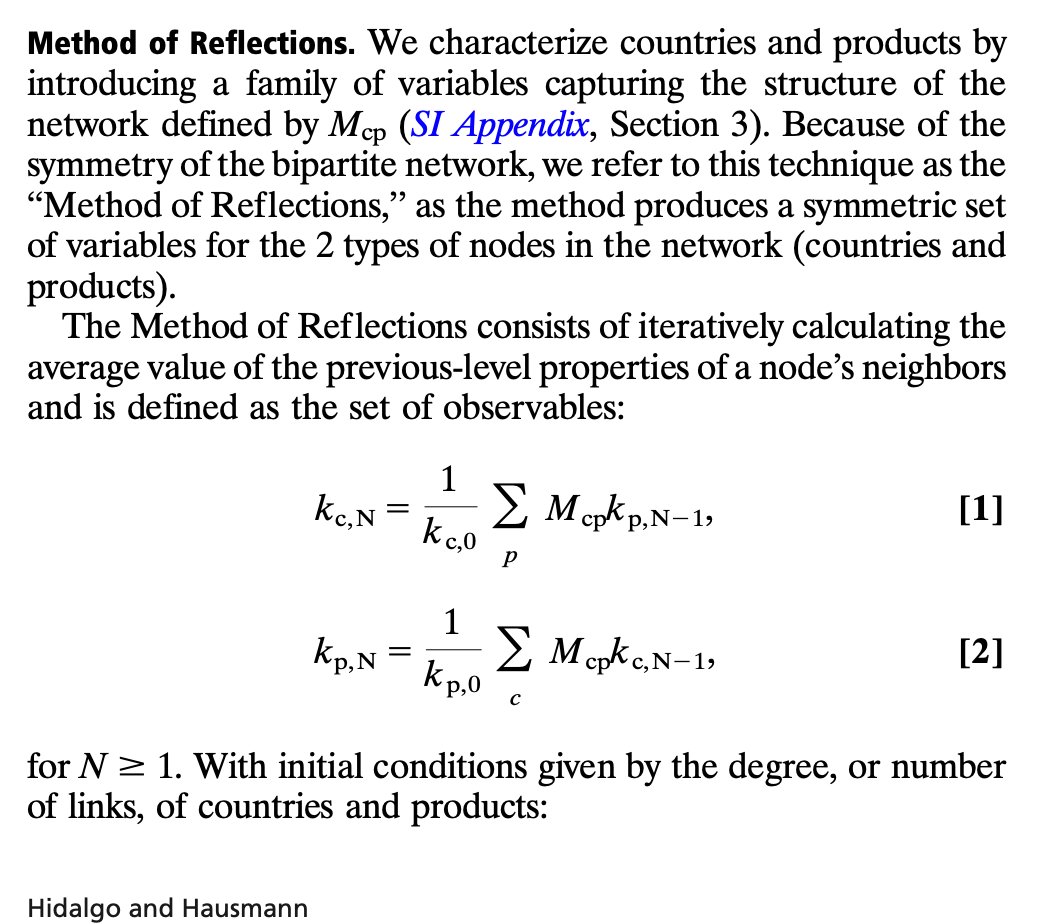

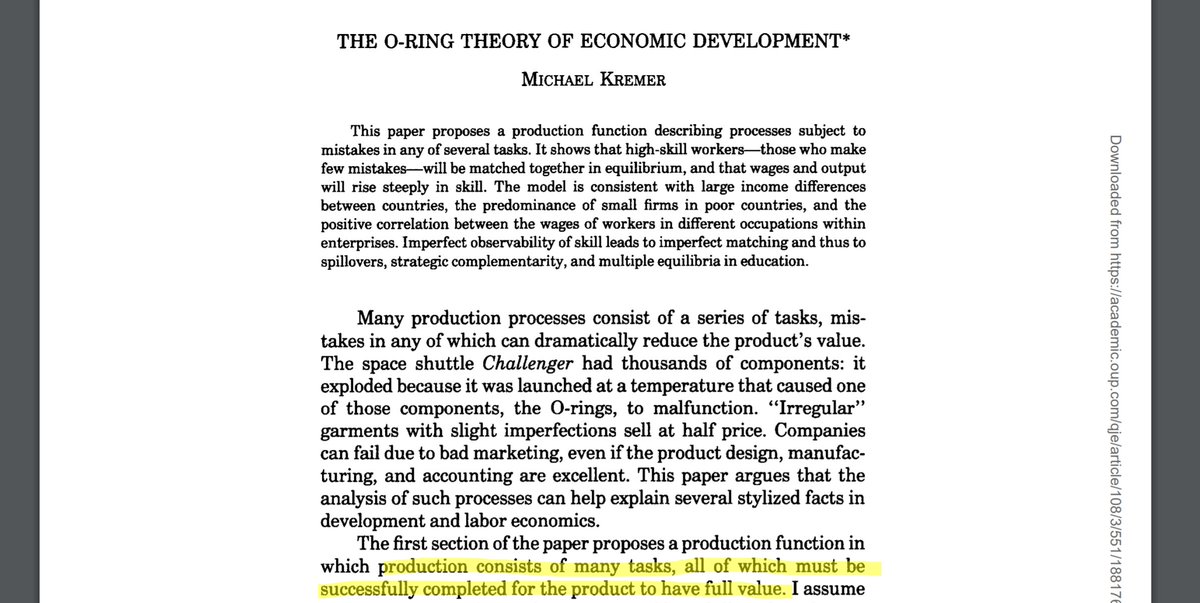

A key ingredient in the analogy is the high complementarity in production memorably discussed by Kremer (QJE 93). Complementarities in production are a huge deal! In finance, a few counterparties failing can destroy you. In production, it might take one small missing part.

7/

7/

Blanchard and Kremer traced the implications of this when there are large institutional changes. But the aggregation of O-ring production has important implications in crises like the present one, with shortages everywhere.

8/

8/

Of course, firms optimize against these risks. They maintain inventories and maintain multiple suppliers. What are the aggregate implications? There are two literatures that are relevant here. One is from operations -- e.g.,

pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.128…

pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.128…

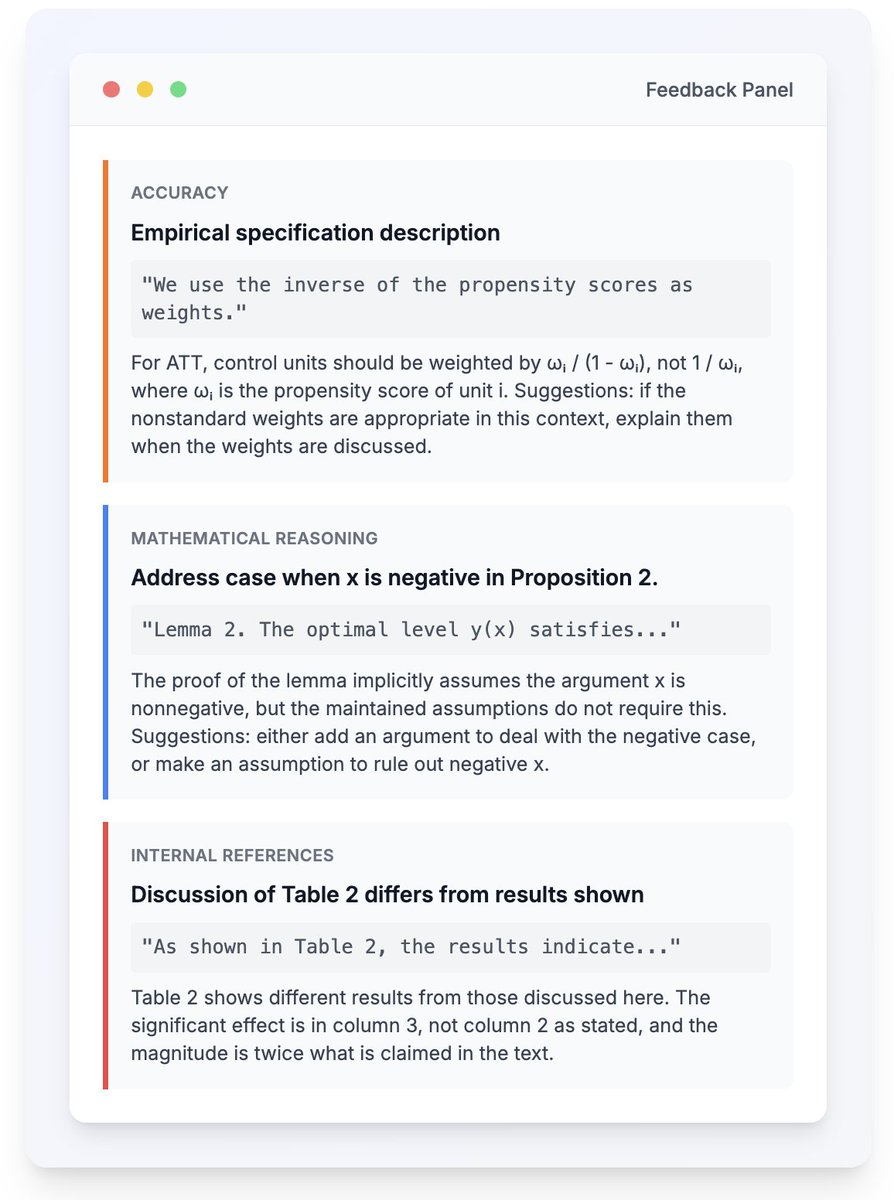

There can be severe externalities, and it may not be in firms' interest to make themselves more robust: by correlating the kinds of shocks they are exposed to, they might make more profits but make the system more fragile in the aggregate.

10/

10/

There are two threads one can follow from this point. One of them incorporates some of these forces into the production functions of a canonical networked production model and analyzes its reaction to (formally small) TFP shocks.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.398…

11/

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.398…

11/

An exciting, growing literature using standard macro models to explore these themes is surveyed by Carvalho and Tahbaz-Salehi

annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.11…

12/

annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.11…

12/

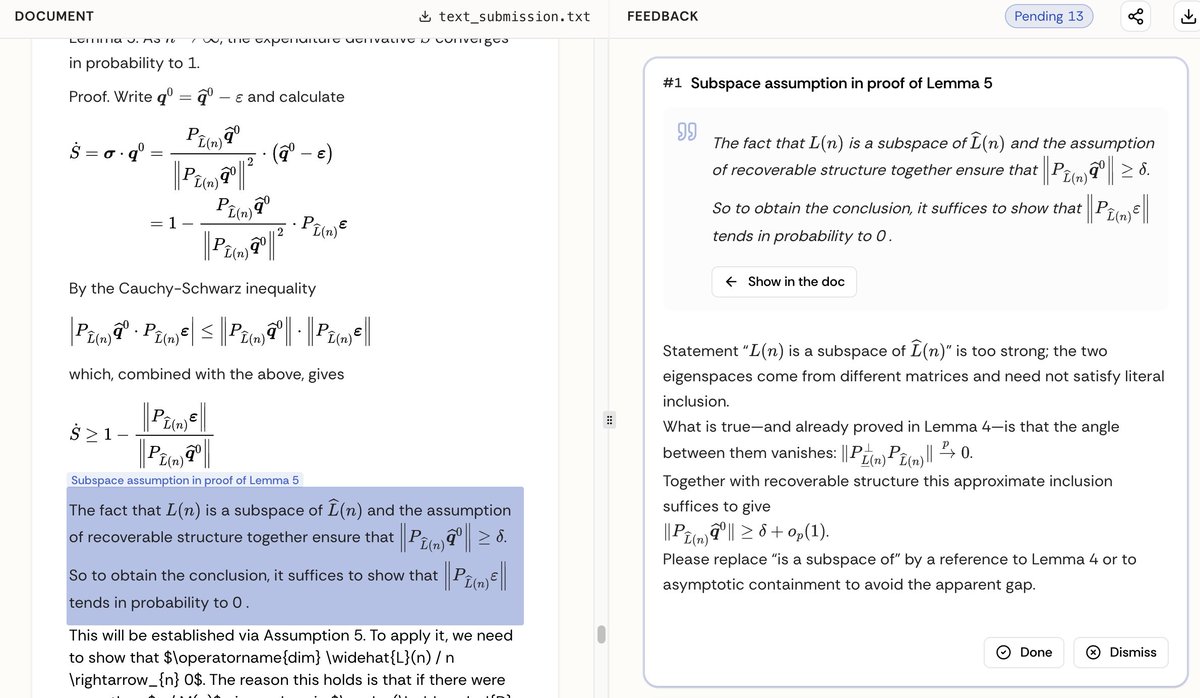

Another thread is more focused on network theory and investigates when we see very large cascades of shutdown. This is more analogous to the financial networks modeling via graph theory, and is studied in this recent paper:

bengolub.net/SNFF

13/

bengolub.net/SNFF

13/

Supply network contagions can look quite different from financial contagions. This is because real complementarities are different: you need *all* inputs to produce (but you can have multiple options for sourcing each of them).

14/

14/

Seoarately, Matt and have just finished the first draft of a survey trying to trace the commonalities Blanchard emphasized through a network theory lens.

(We're not quite ready to circulate, but I'll tweet soon!)

15/

(We're not quite ready to circulate, but I'll tweet soon!)

15/

We have a hope (which we articulate systematically in the survey) that network theory can help in unifying our understanding of the forces behind sudden, systemic disruptions.

15/15

15/15

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh