Can redistributive policies successfully foster inclusive growth in emerging economies?

With @aroopc82 and @Leo_Czajka, we shed new light on this question by studying the case of South Africa, one of the most unequal countries in the world.🧵👇

🔗tinyurl.com/y3p36hdf

With @aroopc82 and @Leo_Czajka, we shed new light on this question by studying the case of South Africa, one of the most unequal countries in the world.🧵👇

🔗tinyurl.com/y3p36hdf

This 🧵 is based on our new working paper, "Can Redistribution Keep Up with Inequality? Evidence from South Africa, 1993-2019".

Part of a broader project on inequality in 🇿🇦, including wealth inequality (tinyurl.com/kxmv8w2w) and wealth taxation (tinyurl.com/xuzb5shm).

Part of a broader project on inequality in 🇿🇦, including wealth inequality (tinyurl.com/kxmv8w2w) and wealth taxation (tinyurl.com/xuzb5shm).

South Africa is a particularly interesting case study to analyze the links between poverty, inequality and growth.

👉One of the most unequal countries in the world.

👉One of the countries that has the most invested in ambitious social programs since the 1990s.

👉One of the most unequal countries in the world.

👉One of the countries that has the most invested in ambitious social programs since the 1990s.

In this paper, we combine numerous data sources to estimate the incidence of government taxes and transfers on poverty and inequality:

👉Household surveys

👉Income tax data

👉National accounts

👉Government budget reports

➡️A new dataset on the distribution of growth 1993-2019.

👉Household surveys

👉Income tax data

👉National accounts

👉Government budget reports

➡️A new dataset on the distribution of growth 1993-2019.

Three findings on growth and ineq in 🇿🇦:

1/ Only the top 10% have seen their pretax income grow since 1993.

2/ Massive rise in redistribution, compensating much of decline in real incomes of the poor

3/ Racial ineq has declined, but mostly due to the rise of a new Black elite.

1/ Only the top 10% have seen their pretax income grow since 1993.

2/ Massive rise in redistribution, compensating much of decline in real incomes of the poor

3/ Racial ineq has declined, but mostly due to the rise of a new Black elite.

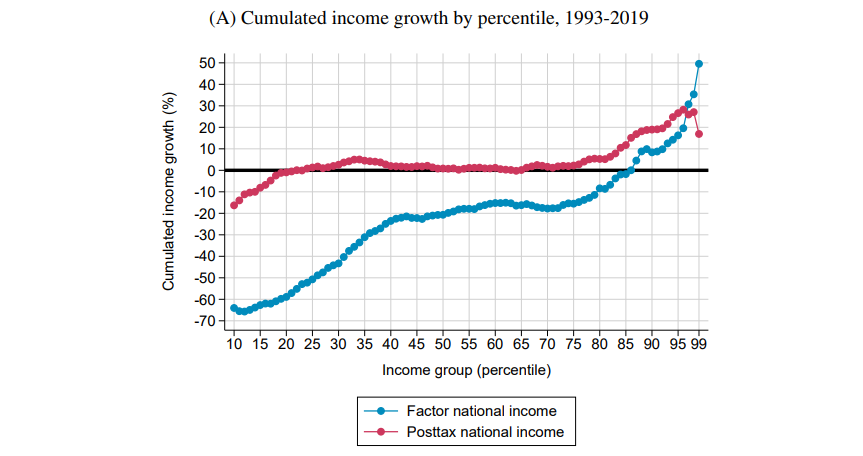

1/ The dramatic rise of South African inequality.

- Only the top 10% have seen their pretax income grow.

- The top 1% have seen their pretax income increase by as much as 50%.

- The poorest half of South Africans have seen their average income *decline* by over 30%.

- Only the top 10% have seen their pretax income grow.

- The top 1% have seen their pretax income increase by as much as 50%.

- The poorest half of South Africans have seen their average income *decline* by over 30%.

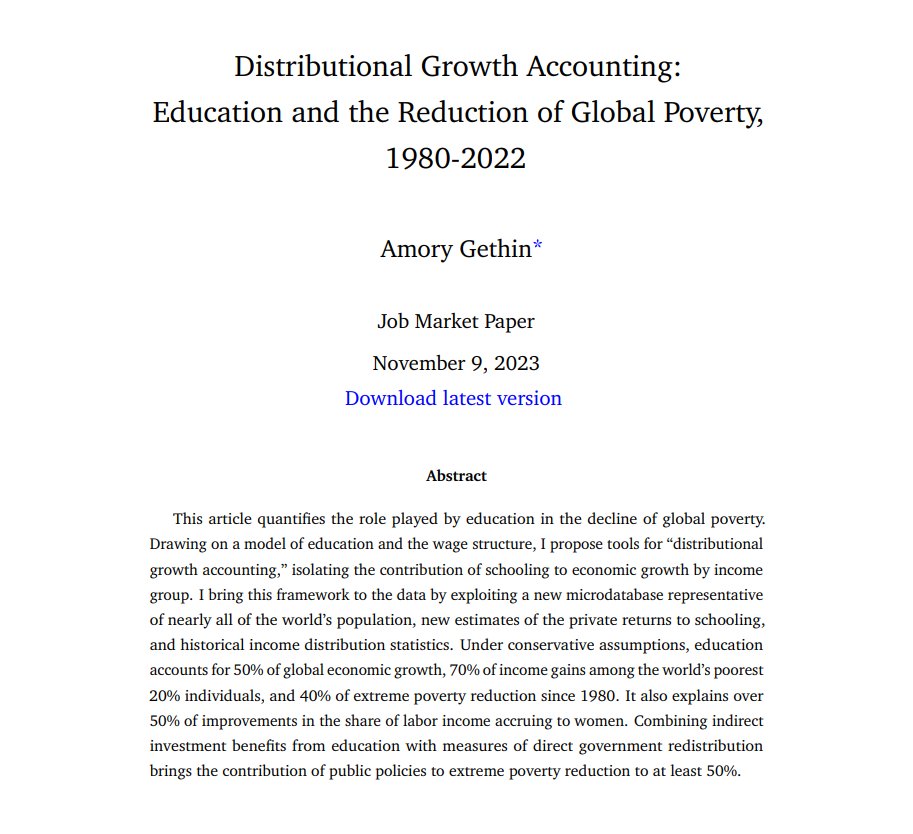

2/ The rise of redistribution

Combining all types of government spending (social grants, education, health, etc.), we find that the share of national income received by the poorest 50% has risen from 8.5% to 12%.

Combining all types of government spending (social grants, education, health, etc.), we find that the share of national income received by the poorest 50% has risen from 8.5% to 12%.

2/ The rise of redistribution

Much of the rise in transfers can be attributed to education and health expenditure, which have become both larger and more progressive.

Much of the rise in transfers can be attributed to education and health expenditure, which have become both larger and more progressive.

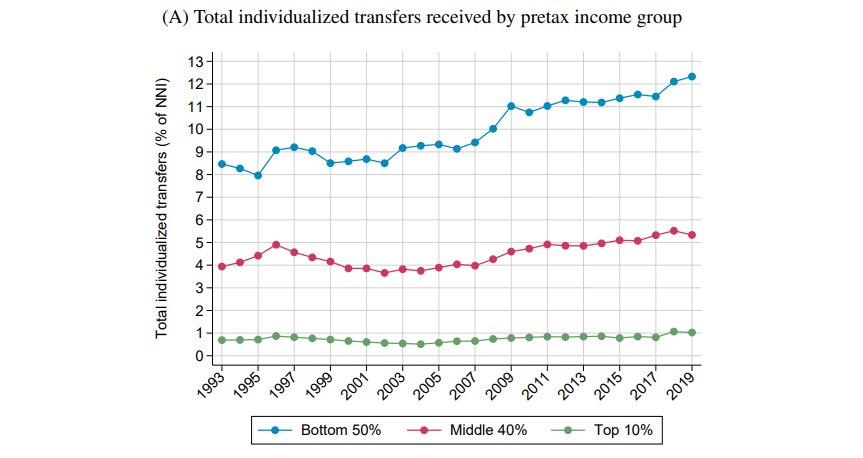

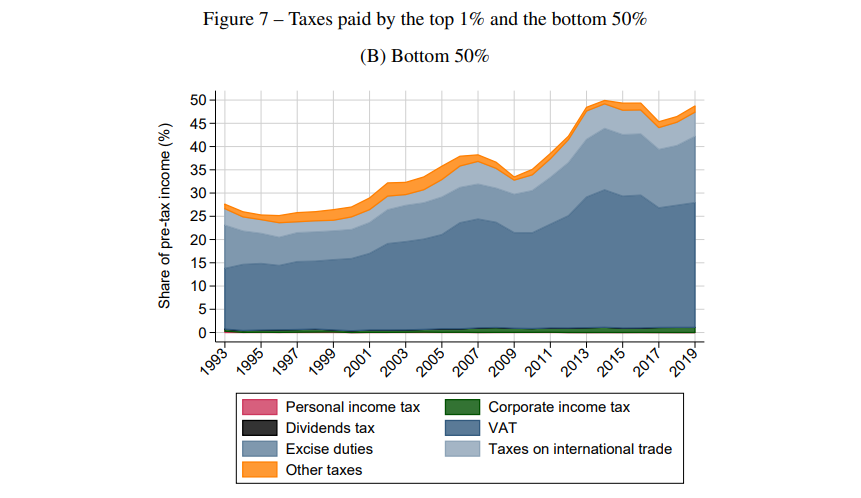

2/ The rise of redistribution

However, part of the increase in transfers has been financed by a higher tax burden on the bottom 50%, due to the rise of indirect taxes.

However, part of the increase in transfers has been financed by a higher tax burden on the bottom 50%, due to the rise of indirect taxes.

2/ The rise of redistribution

All in all, the redistributive policies implemented by the SA government since 1993 have almost fully compensated the decline in pretax incomes at the bottom.

Yet they have failed to tackle the rise of inequality at the top.

All in all, the redistributive policies implemented by the SA government since 1993 have almost fully compensated the decline in pretax incomes at the bottom.

Yet they have failed to tackle the rise of inequality at the top.

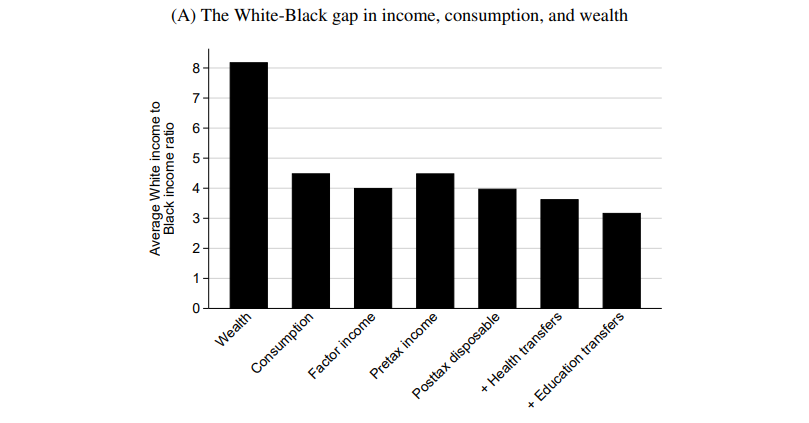

3/ The persistence of racial inequality

Racial inequality in South Africa continues to reach extreme levels. In 2019, the average White adult owned 8 times more wealth than the average Black/African adult, and consumed over 4 times more.

Racial inequality in South Africa continues to reach extreme levels. In 2019, the average White adult owned 8 times more wealth than the average Black/African adult, and consumed over 4 times more.

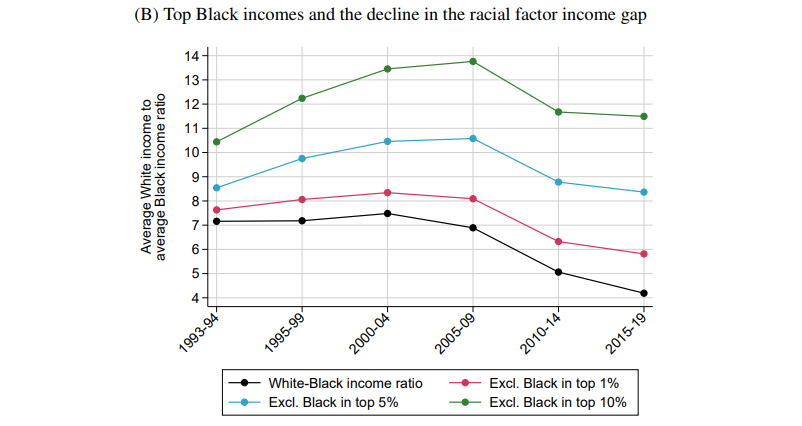

3/ The persistence of racial inequality

Racial inequalities have declined since 1993. But they have only declined because of the rise of a new Black elite; the gap between the average White earner and the bottom 90% of Black earners has remained stable.

Racial inequalities have declined since 1993. But they have only declined because of the rise of a new Black elite; the gap between the average White earner and the bottom 90% of Black earners has remained stable.

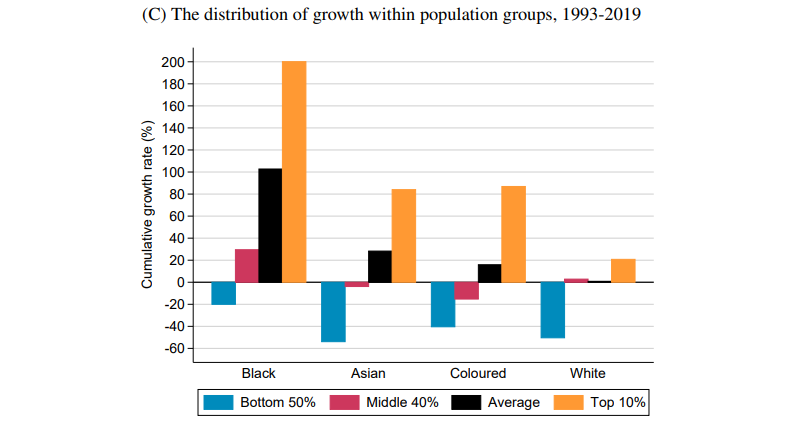

3/ The persistence of racial inequality

Inequality has also increased within all population groups. The boom of top Black incomes has been exceptionally pronounced (+200%). The poorest 50% of Black, Asian, Coloured, and White earners have all seen their incomes decline.

Inequality has also increased within all population groups. The boom of top Black incomes has been exceptionally pronounced (+200%). The poorest 50% of Black, Asian, Coloured, and White earners have all seen their incomes decline.

Conclusions:

➡️Critical need to better measure the evolution of redistribution, in particular in-kind transfers and indirect taxes.

➡️The rise of government spending in 🇿🇦 since 1993 has strongly benefitted the poor. Yet it has failed to curb the rise of pretax inequality.

➡️Critical need to better measure the evolution of redistribution, in particular in-kind transfers and indirect taxes.

➡️The rise of government spending in 🇿🇦 since 1993 has strongly benefitted the poor. Yet it has failed to curb the rise of pretax inequality.

Thanks to my amazing co-authors @aroopc82 from @Wits_SCIS and @Leo_Czajka from @WIL_inequality and @LIDAM_UCLouvain, as well as great feedback and inspiration from suggestions and work by @IngridWoolard @MurrayLeibbrand @pierrebachas @ihsaanbassier @joshbudlender among many.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh